Today’s #manuscriptmonday is all about the most famous story from the Bible that’s not actually from the Bible: The story of the woman caught in adultery (a 🧵)…

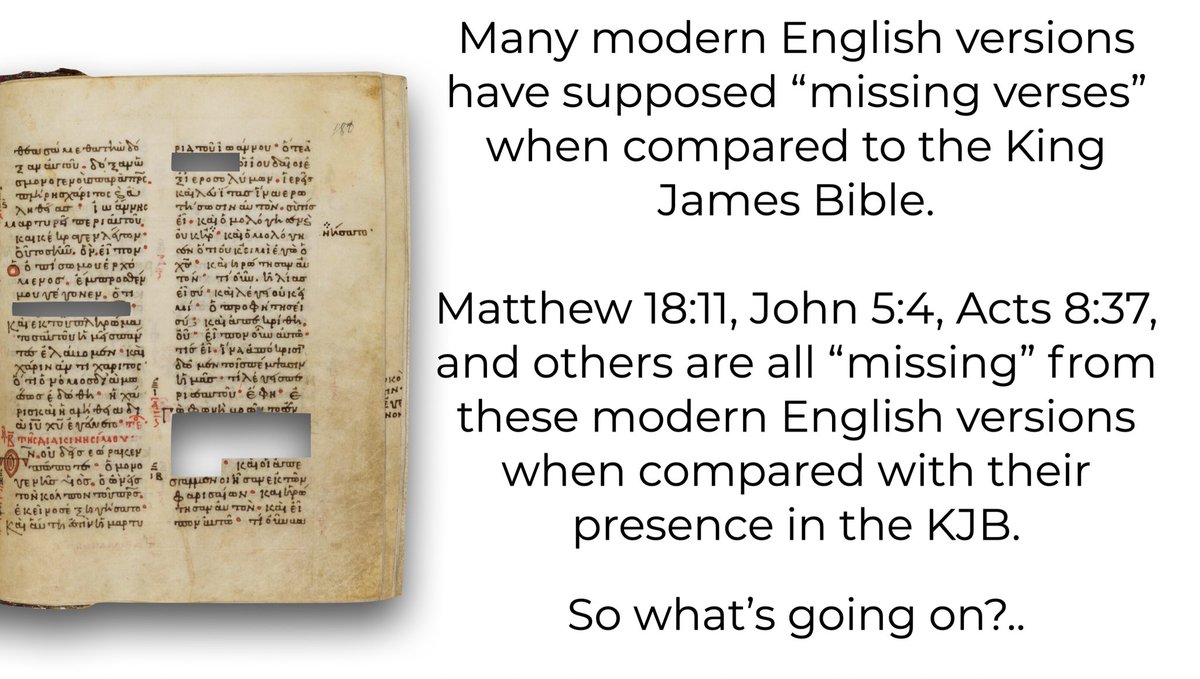

If you look at your modern translation of the Bible you'll notice that at the end of John 7 the text is often sectioned out or bracketed off with the citation note that reads something to the effect of: "The earliest manuscripts and many other ancient witnesses do not have John

7:53-8:17.”

7:53-8:17.”

Part of the trickiness of the

conversation regarding this text, which records the story of the

woman caught in adultery, is that it is not found in any of the earliest Greek texts in the manuscript tradition.

conversation regarding this text, which records the story of the

woman caught in adultery, is that it is not found in any of the earliest Greek texts in the manuscript tradition.

The first surviving manuscript to contain the section is the 4th/5th century Latin/Greek diglot Codex Bezae.

In a few important Medieval manuscripts that contain the story, like the 12th century Minuscule

1, the story is placed after the Gospel of John is finished. At the end of John 7 in Minuscule 1, we find a long

explanatory note stating that the story is not found in most manuscripts, nor mentioned by the early Christians John Chrysostom, Cyril of Alexandria, Theodore of Mopsuestia and the rest.

1, the story is placed after the Gospel of John is finished. At the end of John 7 in Minuscule 1, we find a long

explanatory note stating that the story is not found in most manuscripts, nor mentioned by the early Christians John Chrysostom, Cyril of Alexandria, Theodore of Mopsuestia and the rest.

This has led most experts on this issue to conclude that the story is not original to John's Gospel and was instead a later interpolation.

The vast majority of later manuscripts contain the story, and based upon that, it is still part of the Byzantine liturgy and accepted as scripture by the Greek Orthodox Church. The Story of the Woman Caught in Adultery is likewise included in the Latin Vulgate, and therefore, utilized by the Roman Catholic Church.

Virtually all Protestant Bibles (that I'm aware of at least) contain the passage, albeit with some sort of indication of differentiation within the text.

The conversation about its exclusion within copies of the Gospel of John is ancient. St. Augustine famously argued that it was original but is often lacking from manuscripts due to scribes worrying that that "their wives would see in it a license to sin.”

Literature for the first millennium provides little additional confidence, for with the exception of Didymus the Blind, none of the Greek fathers (e.g., Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria, Origen, etc.) mention the passage.

Literature for the first millennium provides little additional confidence, for with the exception of Didymus the Blind, none of the Greek fathers (e.g., Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria, Origen, etc.) mention the passage.

One must admit that the narrative has the ring of an authentic Jesus story. The Pharisees judgementalism, their intentions to test and trap Jesus, Jesus's cleverness in pointing out their hypocrisy, combined with his

forgiveness, grace, and warning for the woman to "go and sin no more." All of this has the tune of a genuine Jesus account.

But did John write it though? I don't think so, and that matters.

forgiveness, grace, and warning for the woman to "go and sin no more." All of this has the tune of a genuine Jesus account.

But did John write it though? I don't think so, and that matters.

John in his Gospel admits that "there are also many other things which Jesus did, which if they were written one after the other, I suppose that even the world itself could not contain the books that would be written (John 21:25).

We should still be focused on what was originally written by the author, and not a scribe decades or centuries after the fact.

We should still be focused on what was originally written by the author, and not a scribe decades or centuries after the fact.

The grammar, syntax, and word usage in the passage are markedly different than the rest of the Gospel.

It's lack in the earliest manuscripts and its silence from Greek writers is a quietness that speaks a little too loudly on the subject.

It's lack in the earliest manuscripts and its silence from Greek writers is a quietness that speaks a little too loudly on the subject.

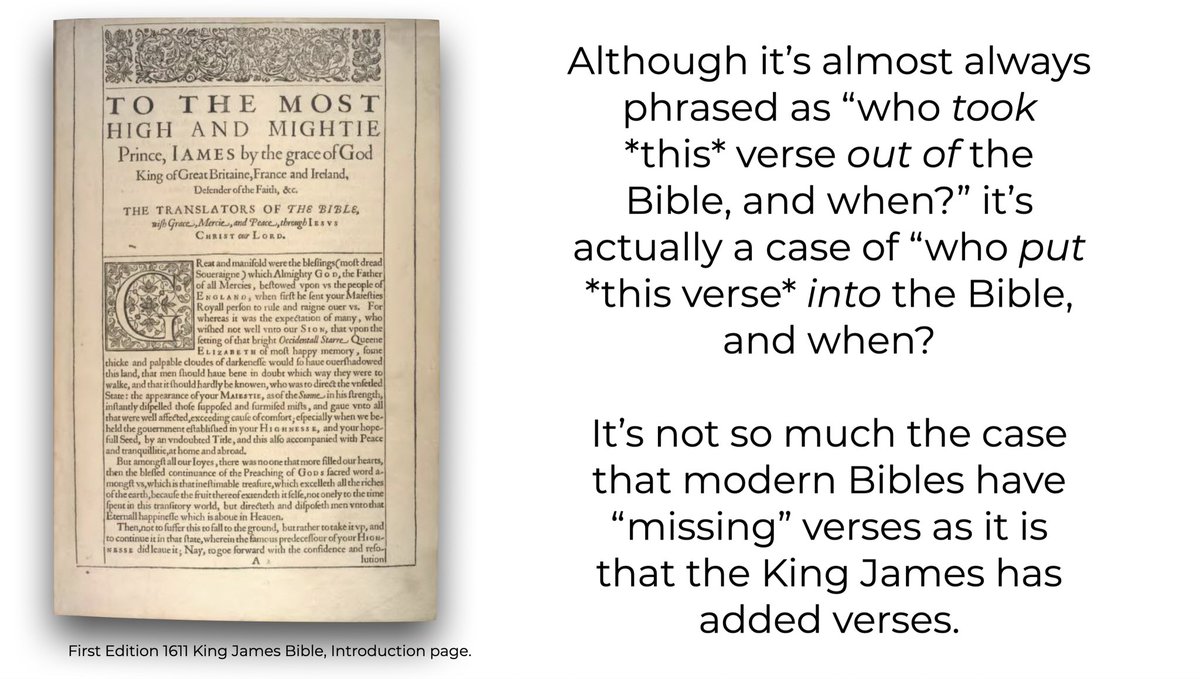

Nonetheless, the transparency in modern translations concerning its authenticity (or lack thereof) should

encourage us! We can pin-point these additions in the history of the text of the Bible and today's versions have no qualms sharing that reality.

encourage us! We can pin-point these additions in the history of the text of the Bible and today's versions have no qualms sharing that reality.

Serious questions concerning the authenticity of passages your modern translation will almost certainly (as we can see with the example of John 7:53-8:11) note it for the reader somewhere visible — either in the body of the text or within a citation.

Despite it almost certainly not being original to the Gospel of John, that does not disqualify it from being a historically authentic Jesus story. The traditions that contain the story are very old and have been highly treasured throughout Church history — even by those throughout the centuries who have questioned its biblical authenticity.

See last week’s #manuscriptmonday

https://twitter.com/wesleylhuff/status/1985325462088978890

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh