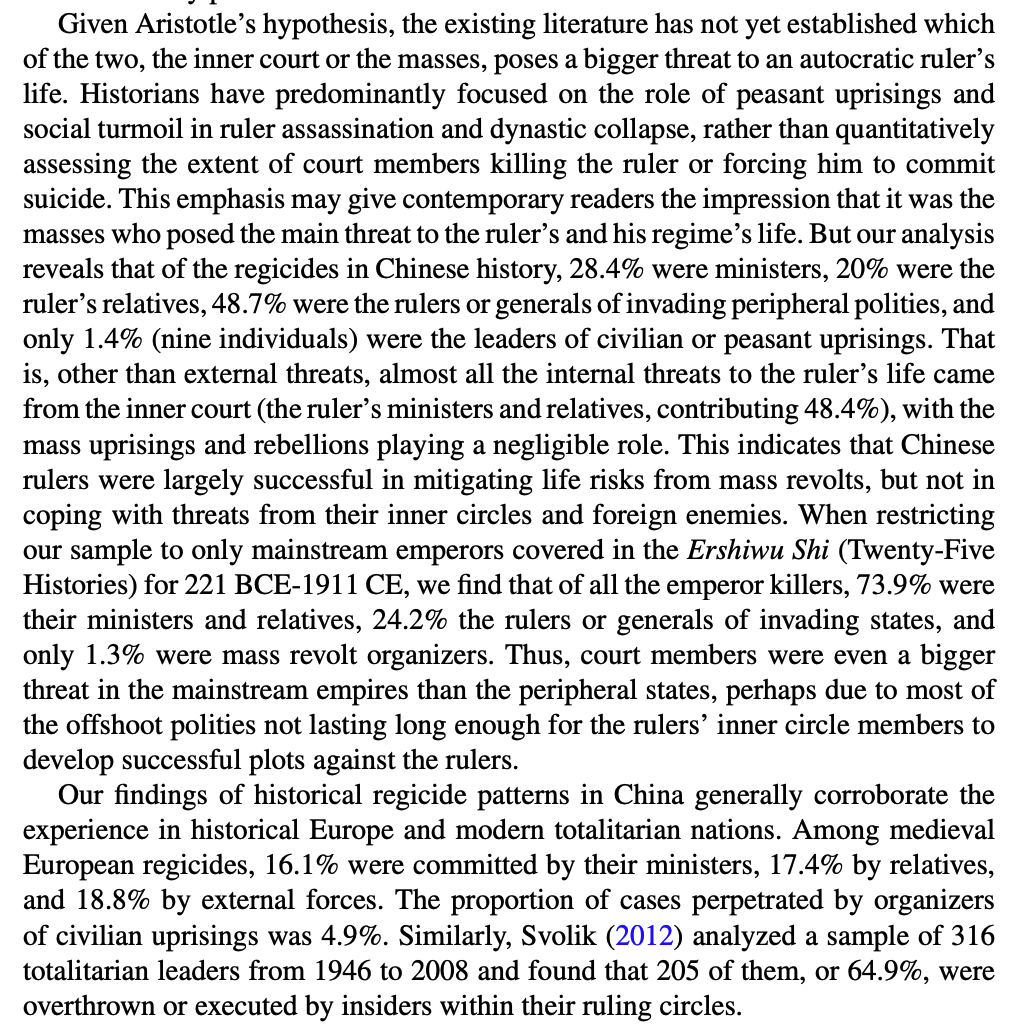

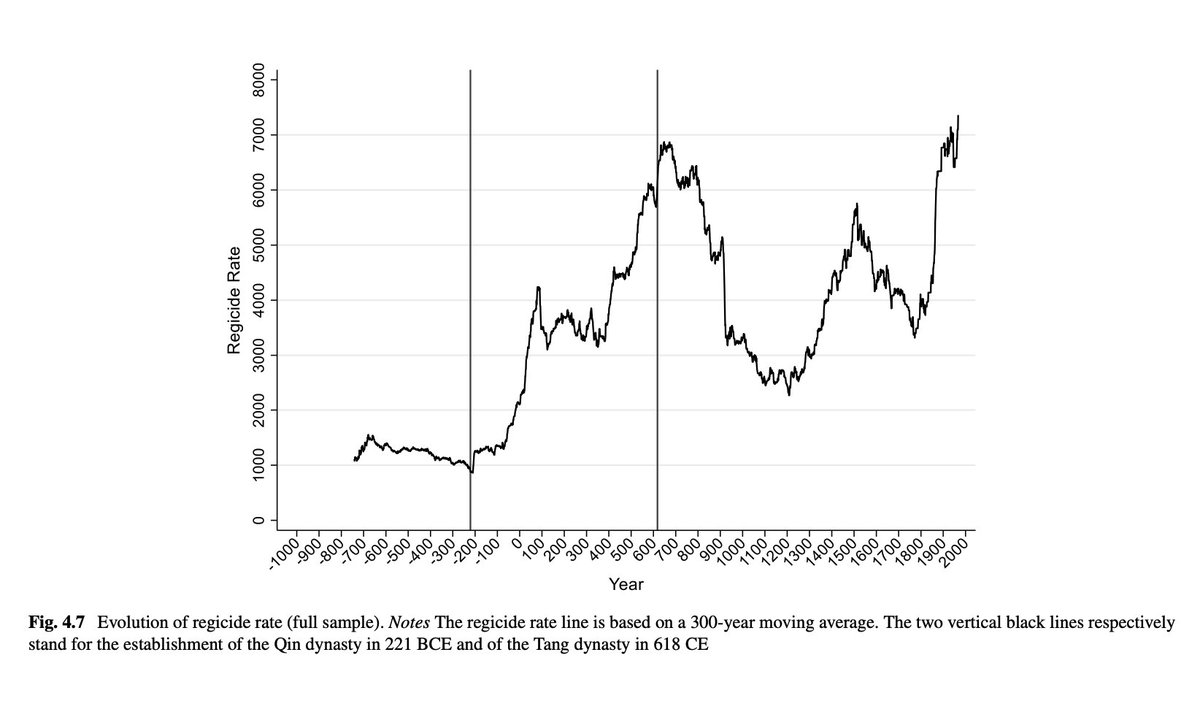

Historically, regicide was an epidemic. It was safer to fight in a war than to be a Chinese Emperor or European King.

But who killed the kings, historically speaking?

Mostly: other elites in the inner circle.

Of post Qin unification Emperors that died on the throne, 70%+ were killed by their the inner court, (ministers, eunuchs, relatives etc).

Europe was a bit more varied, but roughly 35% of European kings that died on the throne did so at the hands of their own ministers or family members.

Ironically, mass revolts, which have received so much theorizing and historic attention, have rarely been responsible for regicide. Just 1% in China and 5% across Europe.

In contemporary totalitarian regimes, estimates are that of those overthrown or executed, insiders within their ruling circles were responsible for 64.9%.

But who killed the kings, historically speaking?

Mostly: other elites in the inner circle.

Of post Qin unification Emperors that died on the throne, 70%+ were killed by their the inner court, (ministers, eunuchs, relatives etc).

Europe was a bit more varied, but roughly 35% of European kings that died on the throne did so at the hands of their own ministers or family members.

Ironically, mass revolts, which have received so much theorizing and historic attention, have rarely been responsible for regicide. Just 1% in China and 5% across Europe.

In contemporary totalitarian regimes, estimates are that of those overthrown or executed, insiders within their ruling circles were responsible for 64.9%.

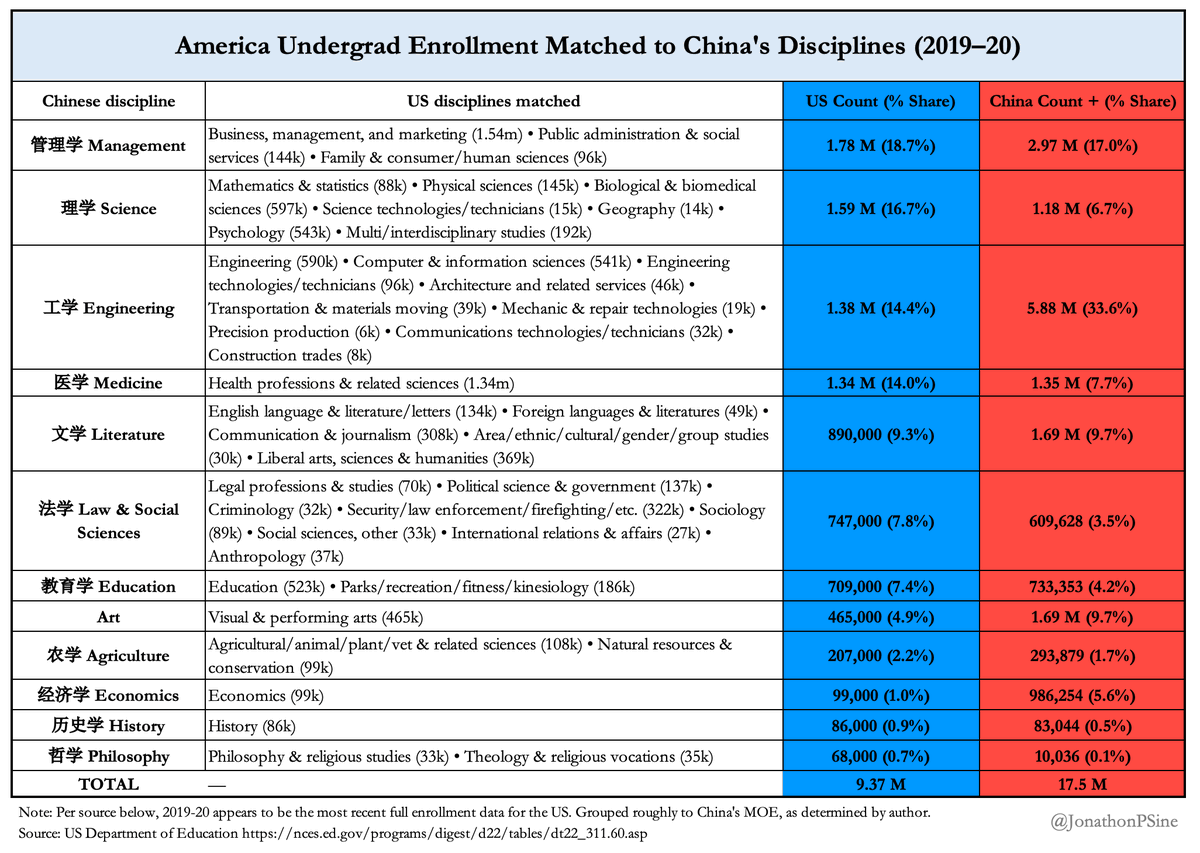

https://x.com/JonathonPSine/status/1994496492091183357

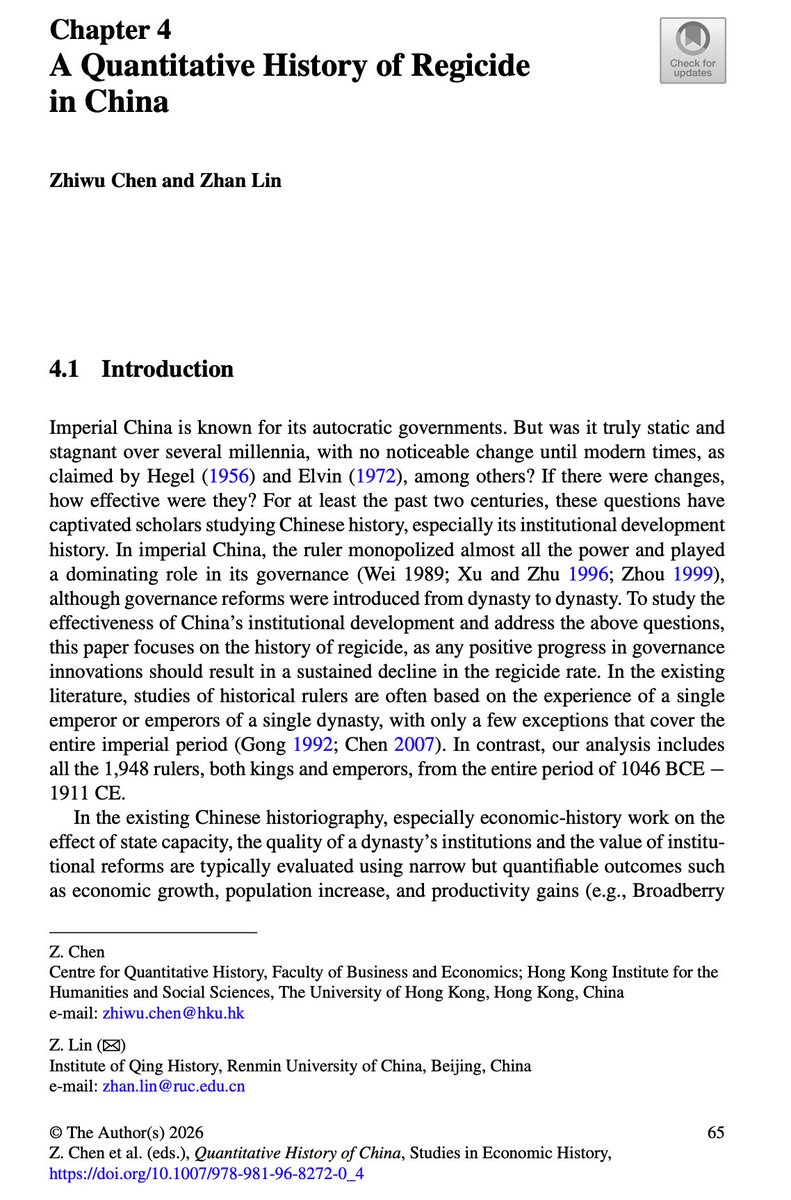

Source for the above is page 68, chapter 4 "A Quantitative History of Regicide in China," in the Quantitive History of China book in the QT.

"Using data on the deaths of 1,513 kings from 45 European kingdoms between 600 and 1800 CE, Eisner (2011) found a regicide ratio of 22%...

Among the 1,948 rulers in our full sample, 695 were victims of regicide, accounting for 35.7%."

Among the 1,948 rulers in our full sample, 695 were victims of regicide, accounting for 35.7%."

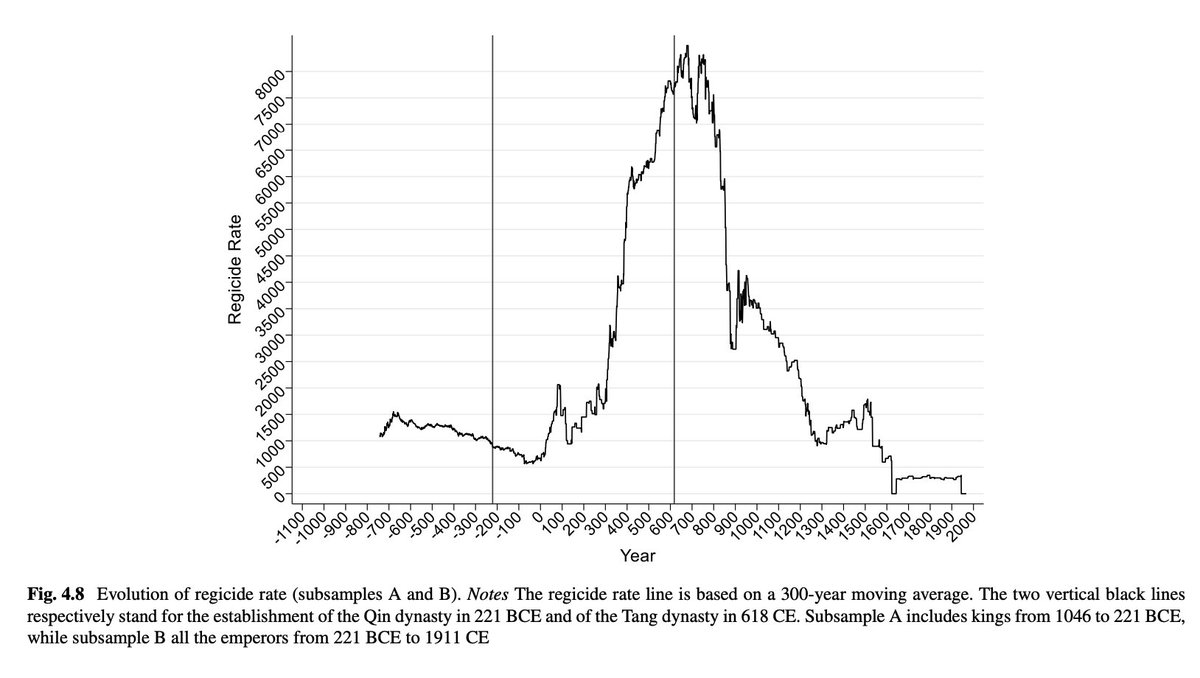

The authors compile the most extensive list of Chinese rulers yet to get at this question. Broken into three subsamples.

A: pre-Qin kings

B: emperors captured in the Ershiwu Shi (Twenty-Five Histories)

C: all post-Qin rulers of peripheral and rebel regimes within the territorial boudnaries established by the Qing at its height.

A: pre-Qin kings

B: emperors captured in the Ershiwu Shi (Twenty-Five Histories)

C: all post-Qin rulers of peripheral and rebel regimes within the territorial boudnaries established by the Qing at its height.

The subsamples tell very different stories.

It remained risky to be a ruler in the periphery (largest N of the sample). Risk peaking in the Qing.

But post-Tang, China's Emperor grew safer and safer.

It remained risky to be a ruler in the periphery (largest N of the sample). Risk peaking in the Qing.

But post-Tang, China's Emperor grew safer and safer.

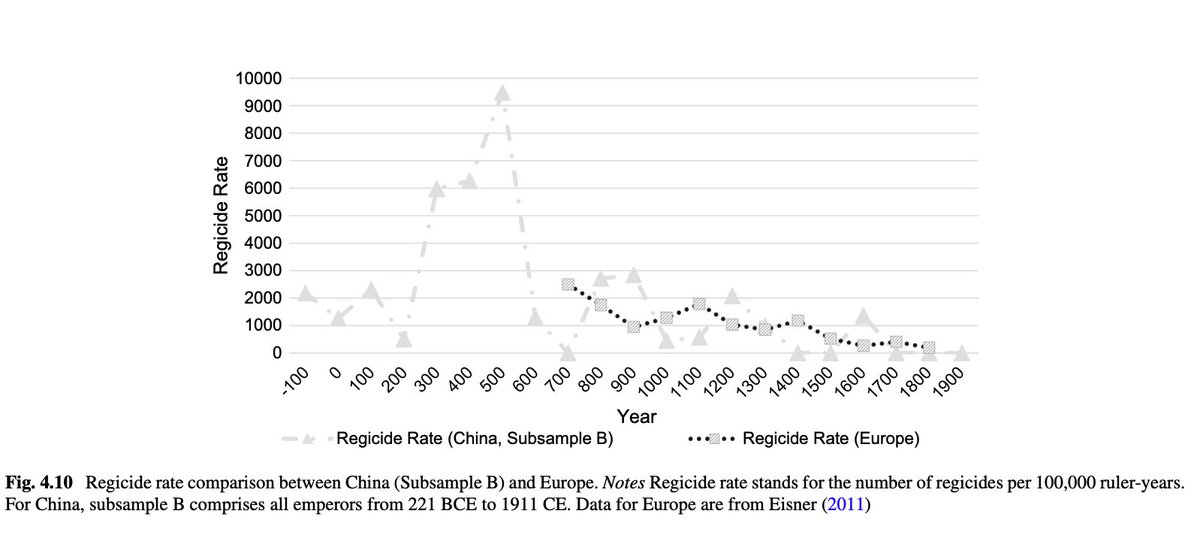

The post 600 AD regicide rates in Europe vs China are very comparable, both declining steadily over time.

(uses the 25 Histories sample of emperors for China, i.e. subsample B's smaller group of officially recognized rulers)

(uses the 25 Histories sample of emperors for China, i.e. subsample B's smaller group of officially recognized rulers)

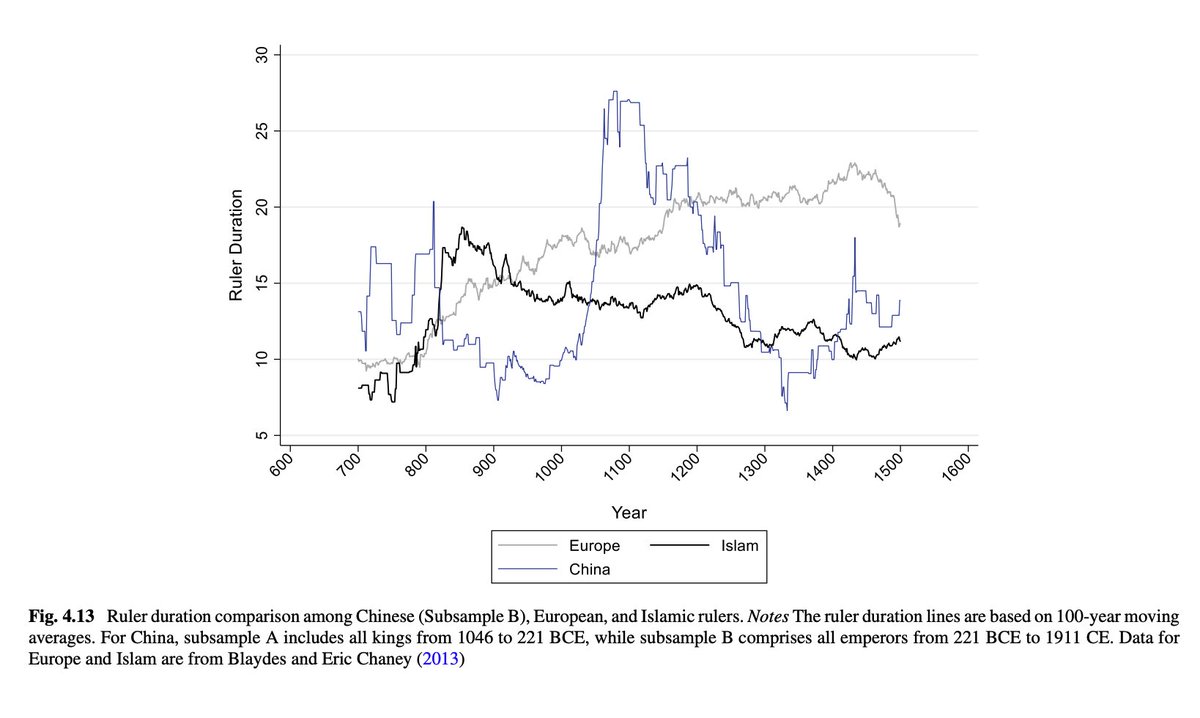

In contrast to some recent accounts (The Rise and Fall of the EAST), the data on ruler longevity here don't appear to show secular increase over time.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh