1/

Turns out @profplum99 just did a 3-hour podcast with @PeterMcCormack (thanks for the shout-out).

Well done!

Here is something important to understand as we discuss these issues, and it's one reason I believe progress in economics and policy may come from the finance sector.

Turns out @profplum99 just did a 3-hour podcast with @PeterMcCormack (thanks for the shout-out).

Well done!

Here is something important to understand as we discuss these issues, and it's one reason I believe progress in economics and policy may come from the finance sector.

https://twitter.com/PeterMcCormack/status/1999192495469572158

2/

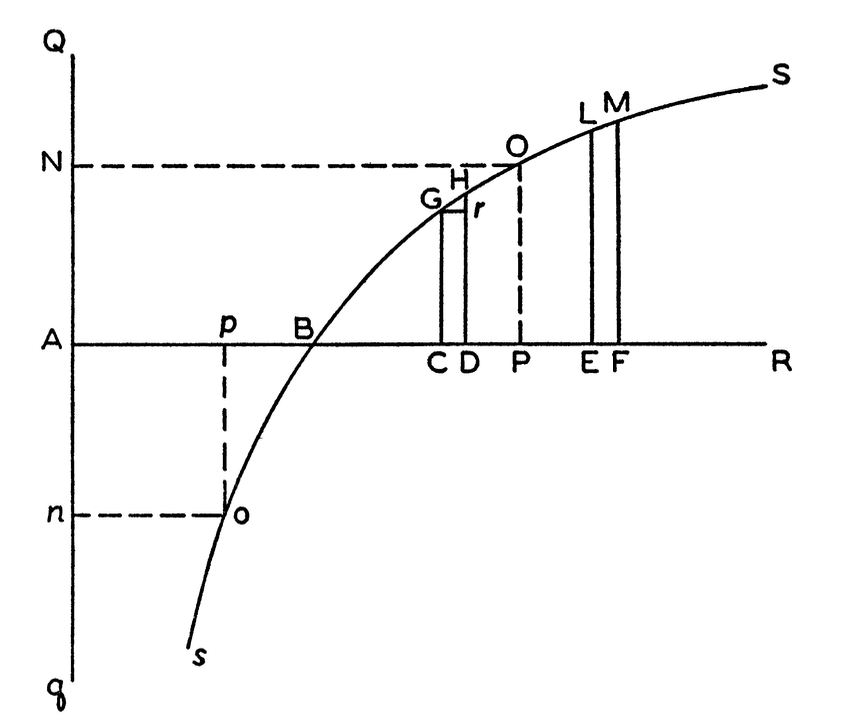

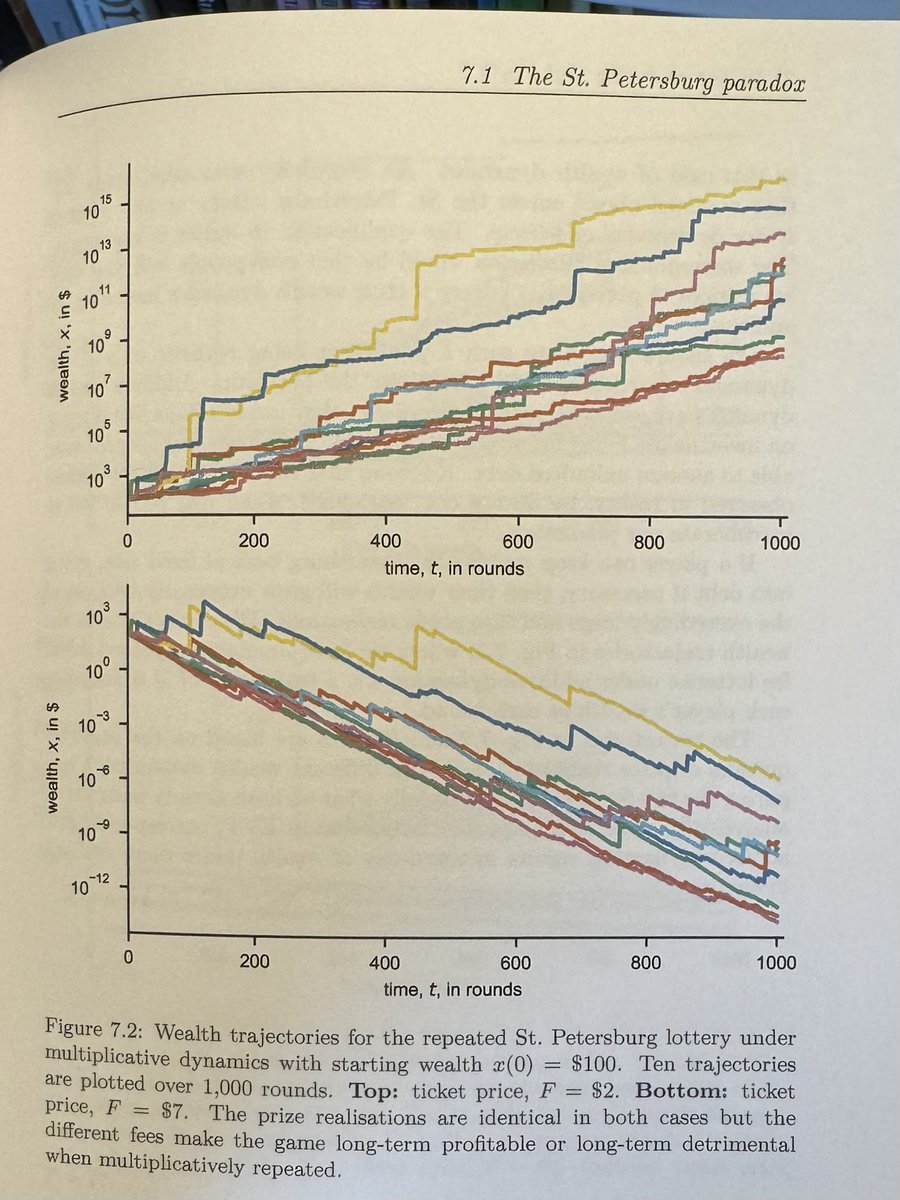

One thing we know about living things is that they self-reproduce. That means they grow multiplicatively.

The reason capitalism feels so alive is that capital and personal wealth do the same. Every finance professional knows this; it's the geometric Brownian motion model.

One thing we know about living things is that they self-reproduce. That means they grow multiplicatively.

The reason capitalism feels so alive is that capital and personal wealth do the same. Every finance professional knows this; it's the geometric Brownian motion model.

3/

So what happens by default to inequality in these systems?

It increases indefinitely. Roughly, one entity ends up dominating. Econophysicists call this "wealth condensation" -- do nothing, let the system run, and wealth condenses into the hands of a small elite.

So what happens by default to inequality in these systems?

It increases indefinitely. Roughly, one entity ends up dominating. Econophysicists call this "wealth condensation" -- do nothing, let the system run, and wealth condenses into the hands of a small elite.

4/

It's a misdiagnosis to believe that malice and conspiracy are required to generate diverging inequality.

Indefinitely increasing inequality is a fundamental mathematical property of multiplicative systems.

Why few economists say this, I don't know. The mathematics knows it.

It's a misdiagnosis to believe that malice and conspiracy are required to generate diverging inequality.

Indefinitely increasing inequality is a fundamental mathematical property of multiplicative systems.

Why few economists say this, I don't know. The mathematics knows it.

5/

I hesitate to speculate politically, but we have to have these conversations now. My sense is that if we want to maintain a healthy middle class, the rich have to sacrifice for it, continually. We have to work to maintain it; it's not what happens "by default."

I hesitate to speculate politically, but we have to have these conversations now. My sense is that if we want to maintain a healthy middle class, the rich have to sacrifice for it, continually. We have to work to maintain it; it's not what happens "by default."

6/

Bitcoin would then not be the solution to this problem. If we dismantle institutions, we just move the system to its unchecked state. In the long run, that leads to wealth condensation, meaning some form of feudalism, I suppose.

We need institutions to maintain a middle class.

Bitcoin would then not be the solution to this problem. If we dismantle institutions, we just move the system to its unchecked state. In the long run, that leads to wealth condensation, meaning some form of feudalism, I suppose.

We need institutions to maintain a middle class.

7/

Of course institutions can be corrupt.

But diverging inequality can be a sign of institutions that are too weak to do their job of maintaining reasonably equal opportunity and enabling a middle class. Not too strong and corrupt.

Of course institutions can be corrupt.

But diverging inequality can be a sign of institutions that are too weak to do their job of maintaining reasonably equal opportunity and enabling a middle class. Not too strong and corrupt.

8/

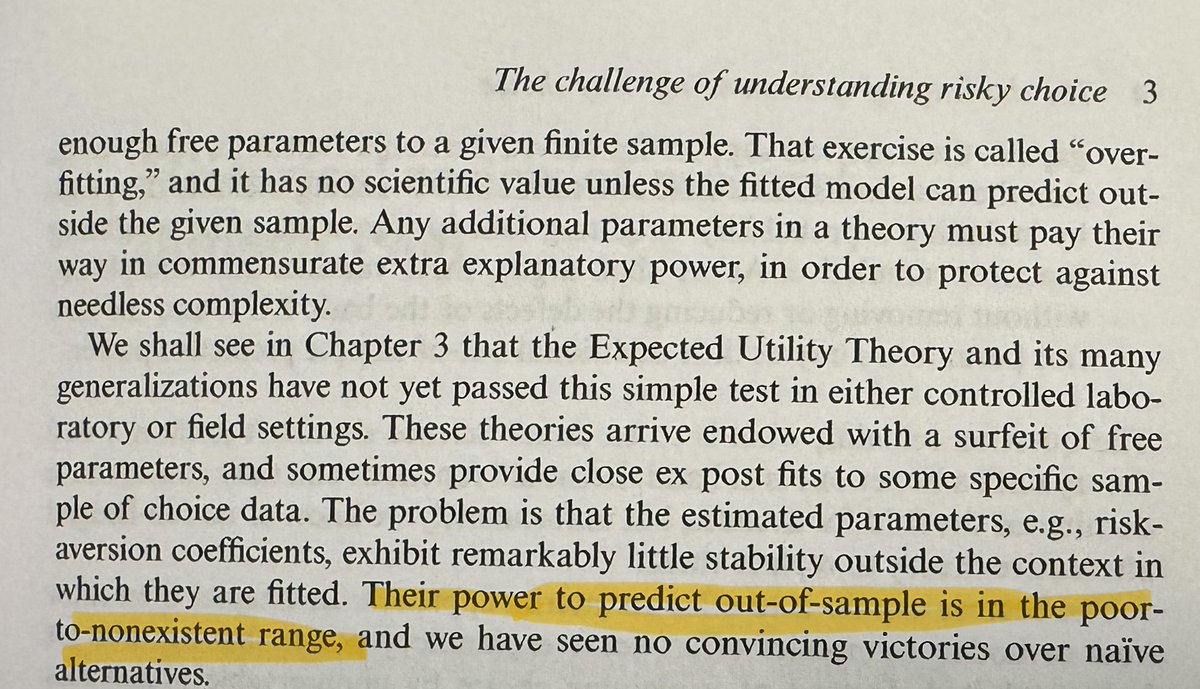

The message: if we do nothing, things diverge.

Economics textbooks of the 1950s knew this; but somewhere in the 1970s or 1980s a different narrative took hold, namely that by not interfering with markets, things will equilibrate.

No. That's not what these systems do.

The message: if we do nothing, things diverge.

Economics textbooks of the 1950s knew this; but somewhere in the 1970s or 1980s a different narrative took hold, namely that by not interfering with markets, things will equilibrate.

No. That's not what these systems do.

10/

Obviously: happy to be challenged on all of the above, but I felt it was worth throwing this into the debate.

Obviously: happy to be challenged on all of the above, but I felt it was worth throwing this into the debate.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh