Most people just don't understand the immune system, its different components, how covid weakens it, and what that leaves you vulnerable to.

We tend to imagine immunity as a single light switch.

On or off.

Maybe on a dimmer switch.

Strong or weak.

On or off.

Maybe on a dimmer switch.

Strong or weak.

In reality it is a whole set of tightly coordinated systems, and covid happens to damage several of the ones you rely on for dealing with infections that hide inside your own cells.

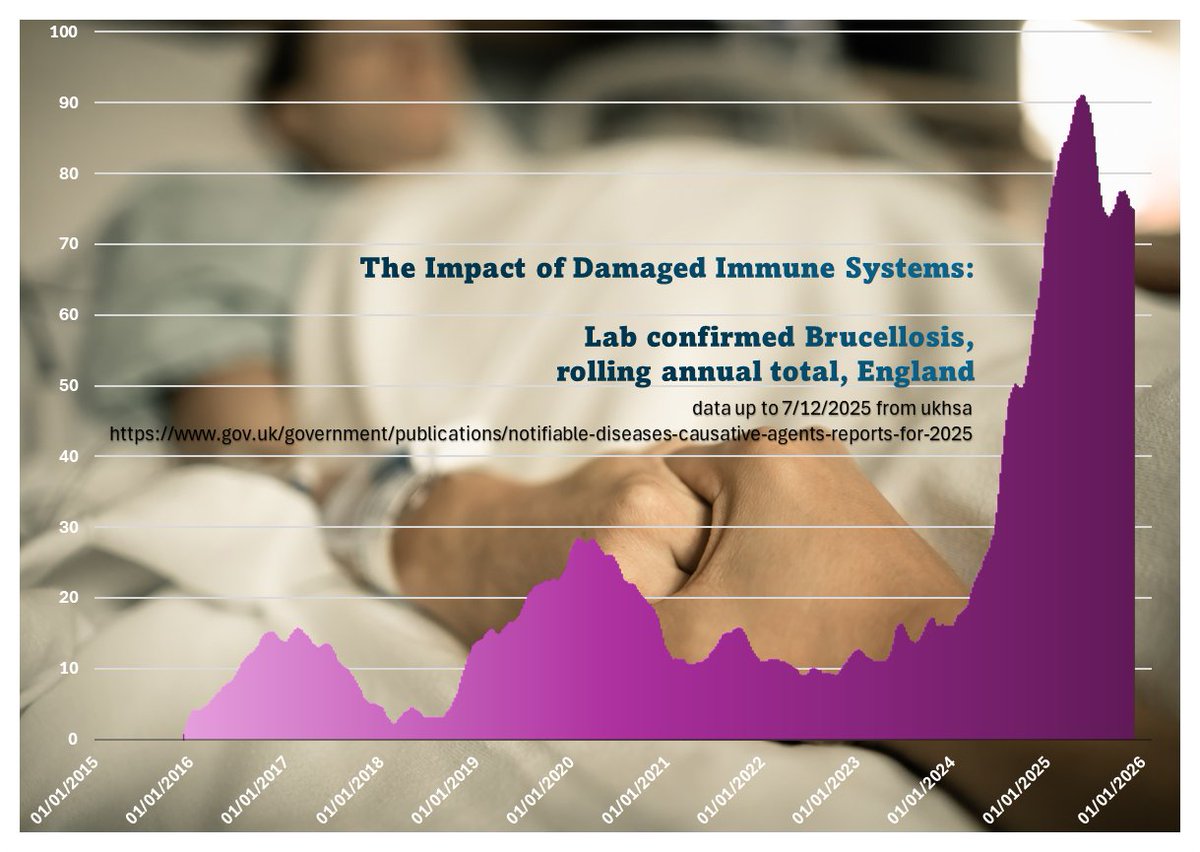

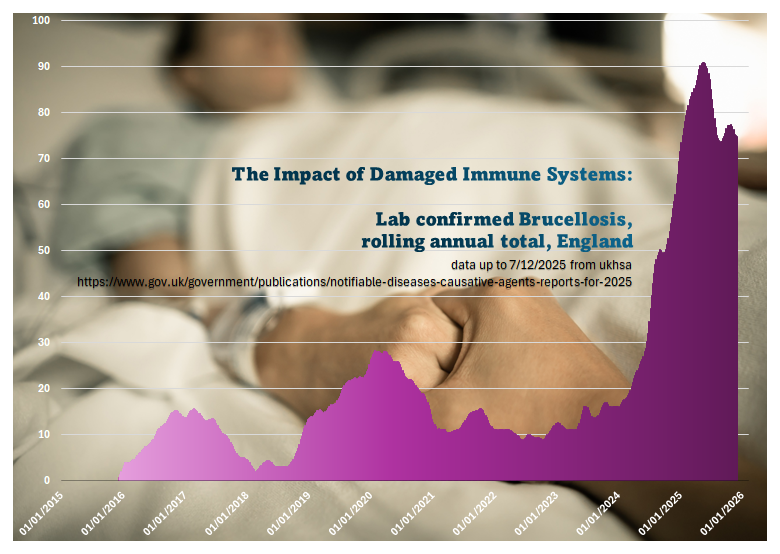

I mean this graph is almost the textbook answer to the question:

"What would happen to the number of Brucellosis cases if repeat covid infections caused damage to the different functions of the immune system?"

"What would happen to the number of Brucellosis cases if repeat covid infections caused damage to the different functions of the immune system?"

Brucella is not a typical bug.

It is an 'intracellular' bacterium.

It slips into macrophages (a type of immune cell used to clean up microbes and debris) and uses *them* as its safe house.

It is an 'intracellular' bacterium.

It slips into macrophages (a type of immune cell used to clean up microbes and debris) and uses *them* as its safe house.

That means that to deal with the brucella invasion, your immune system has to recognise that a cell looks wrong, send the right interferon gamma signals to indicate there's a problem, bring in the right T cells...

and then kill that infected cell without causing too much collateral damage.

If *any* step fails, brucella digs in.

Brucella makes you ill by *persisting*.

It doesn't usually cause dramatic symptoms at first.

It doesn't usually cause dramatic symptoms at first.

Fever that comes and goes, deep fatigue, joint pain, night sweats, back pain, and a general sense of being unwell.

It can sit in the body for months or years.

It is slow, it is stealthy, and it causes illness mainly because the immune system cant fully clear it, so the response to the infection - the firefighting and inflammation - drags on.

Chronic brucellosis is basically your immune system fighting a slow wildfire it never quite wins.

And this is exactly the kind of organism that flourishes when covid infection has knocked key systems off balance.

Covid infection weakens interferon gamma responses.

That's the early alert signal for intracellular pathogens. If that signal is weak or delayed, brucella gets a head start.

That's the early alert signal for intracellular pathogens. If that signal is weak or delayed, brucella gets a head start.

Covid infection knocks down and scrambles lymphocytes - the white blood cells that learn specific targets and build long term immune defence.

During and after Covid infection, T cells (the immune systems precision coordinators) drop sharply in many people, and in a proportion they stay low or behave erratically.

Without strong T cell direction, macrophages (the big eater cells that should destroy infected cells) never switch into proper kill mode.

Covid disrupts monocytes and macrophages themselves. Monocytes (the precursor cells that mature into macrophages) and macrophages often come out of covid either exhausted or stuck in an inflammatory but ineffective state.

Brucella loves that, because the exact cells that are meant to kill it instead become long term hiding places.

Covid skews cytokines (chemical signals that tell immune cells what to do) like IL6 and TNF for months. They're meant to be tightly regulated.

Covid infection dysregulates them.

Covid infection dysregulates them.

And when they drift, the immune system loses focus. Intracellular bacteria (pathogens that hide and replicate inside human cells) start slipping through cracks that did not exist before.

Repeat infections stack this damage.

One hit might cause temporary dysfunction.

Several rounds can make interferon responses glitchy, T cells inconsistent, and macrophages chronically unreliable.

One hit might cause temporary dysfunction.

Several rounds can make interferon responses glitchy, T cells inconsistent, and macrophages chronically unreliable.

You do not need a catastrophic collapse for this to matter. A small drop in performance can turn a rare infection into a more common one.

So when you see brucellosis rising after years of stability, this is exactly what you would expect when a population has been repeatedly exposed to a virus that selectively injures the systems needed for intracellular defence.

This is the part that doesn't get shouted about enough.

Covid is not just a respiratory virus.

It is a virus that damages the interferon system, the T cell system, and the macrophage system.

It is a virus that damages the interferon system, the T cell system, and the macrophage system.

As well as a thousand other systems in the body.

And all that cumulative damage grinds people down.

And all that cumulative damage grinds people down.

Reduced energy.

Reduced ability to fight infection.

Reduced capacity to monitor for cancer.

Reduced cognitive function.

Reduced ability to heal.

Reduced ability to fight infection.

Reduced capacity to monitor for cancer.

Reduced cognitive function.

Reduced ability to heal.

Covid doesn't just affect one system.

It affects them all.

It affects them all.

But here, with the example of Brucellosis, it's *exactly* what you would expect to see if more people were struggling with immune dysfunction on the back of Covid infections.

Brucellosis is one example.

It is not the only one.

This thread here... it's just about the lungs:

https://x.com/1goodtern/status/1992290946415751433?s=20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh