1) New blog post: NIH funding for ME/CFS keeps falling.

Last year, we calculated that the NIH funded 23 ME/CFS projects, totalling an investment of $10.1 million. In 2025, however, this amount decreased to $7.4 million for 18 projects.

Last year, we calculated that the NIH funded 23 ME/CFS projects, totalling an investment of $10.1 million. In 2025, however, this amount decreased to $7.4 million for 18 projects.

2) Even if we include funding for Ian Lipkin’s team at Columbia University (which did not appear in the database), the funding still decreased by 7% to $ 9.4 million.

3) Five ME/CFS projects are planned to end in 2026, hinting that the decline will likely continue next year. The influx of new grants is currently too low to reverse the downward trend.

4) In 2025, there were only two new NIH projects on ME/CFS.

One focuses on bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cell (BMMSC)-derived exosomes. These are important in the communication between cells and play a role in modulating the immune system.

One focuses on bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cell (BMMSC)-derived exosomes. These are important in the communication between cells and play a role in modulating the immune system.

5) This exosome project is led by Vladimir Beljanski at Nova Southeastern University. His team will isolate blood cells from patients and expose them to BMMSC-exosomes. Afterwards, they will test mRNA gene expression and mitochondrial function.

They got $224,070 in 2025.

They got $224,070 in 2025.

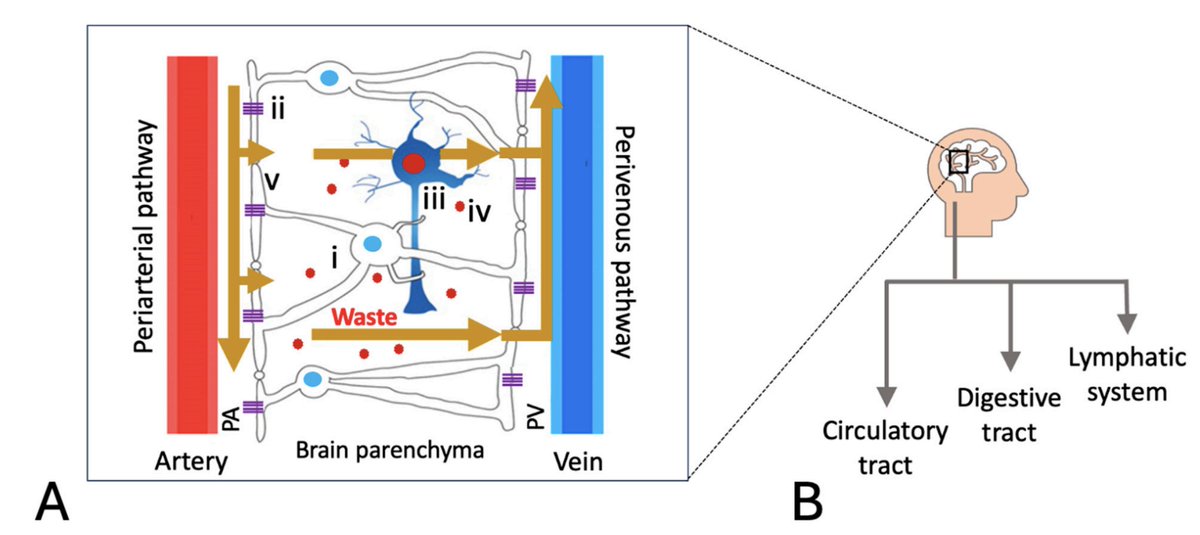

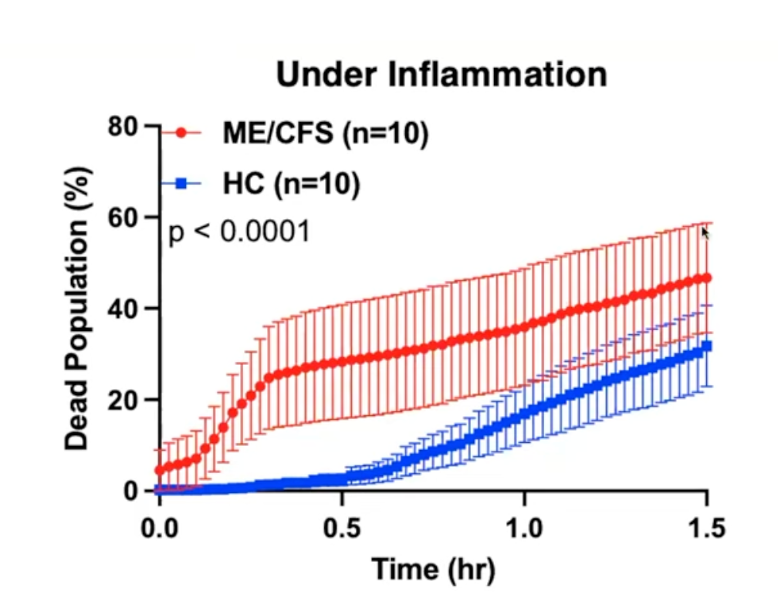

6) The other project is led by Associate Professor Ramasubramanian at San José State University and focuses on red blood cell deformability. Increased stiffness of red blood cells in ME/CFS patients might make it harder to pass through small spaces, such as tiny blood vessels.

7) Ramasubramanian has previously published about this with Ron Davis using a microfluidic device. They suspect that oxidative stress might be the reason why blood cells of ME/CFS patients are less flexible. This new grant will explore this further and received $432,431 in 2025.

8) The level of NIH funding for ME/CFS was already unacceptably low. To be commensurate with its disease burden, it would need to increase roughly 14-fold. Seeing it decrease even more, year after year, feels very unjust for the millions affected by this horrible illness.

10) There's some ambiguity about which projects to include (is it sufficiently about ME/CFS or not?), and we may have missed one, but the overall trend seems clear.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh