Cooking in San Diego: A turquoise, 23-story test of the Permit Streamlining Act's new-and-improved "deemed approved" proviso.

This could turn into a big constitutional battle.

🧵/22

This could turn into a big constitutional battle.

🧵/22

Enacted in 1977, the PSA put time limits on CEQA and other agency reviews of development proposals.

If an agency violated the time limits, the project was to be "deemed approved" by operation of law. Wow!

It proved wholly ineffectual.

/2

If an agency violated the time limits, the project was to be "deemed approved" by operation of law. Wow!

It proved wholly ineffectual.

/2

As @TDuncheon & I explained, courts first decided that the Leg couldn't possibly have meant for a project to be approved before enviro review was complete.

Ergo, CEQA review must be finalized before the deemed-approval clock starts ticking.

/3

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

Ergo, CEQA review must be finalized before the deemed-approval clock starts ticking.

/3

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

Then the courts said they were powerless to remedy CEQA delays, notwithstanding the new time limits in the statute.

The third blow was a decision suggesting that neighbors' "due process" hearing rights trump PSA automatic approvals.

/4law.justia.com/cases/californ…

The third blow was a decision suggesting that neighbors' "due process" hearing rights trump PSA automatic approvals.

/4law.justia.com/cases/californ…

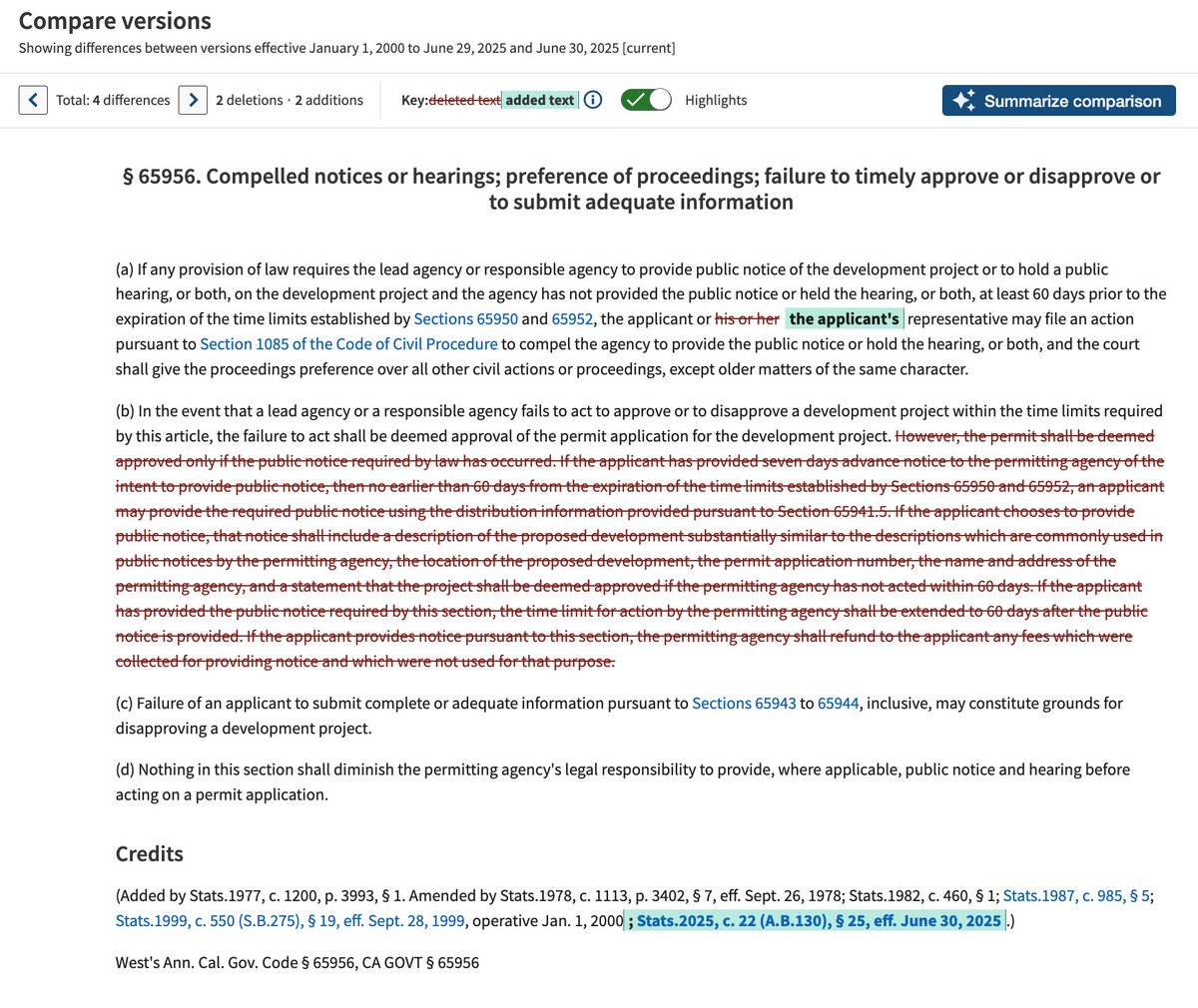

The Leg mustered a partial fix for the due-process issue, declaring that projects couldn't be "deemed approved" without "public notice required by law."

The Leg also established a self-help procedure for applicant to notify public of the possibility of a "deemed approval."

/5

The Leg also established a self-help procedure for applicant to notify public of the possibility of a "deemed approval."

/5

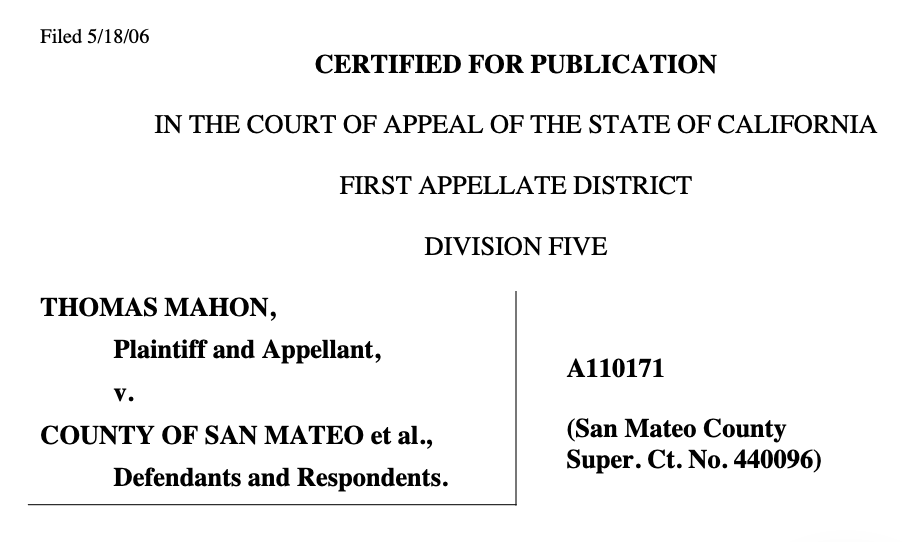

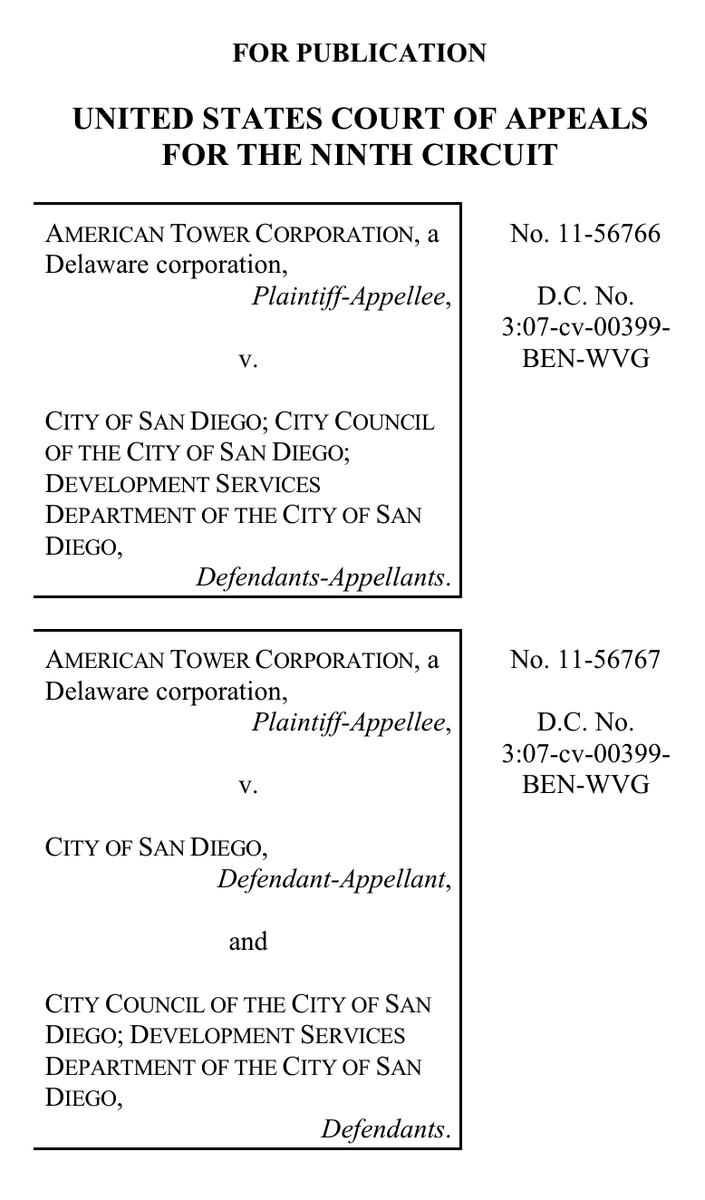

Courts then split on whether advance notice to the public of a potential deemed approval satisfies due process under Horn v. County of Ventura (1979), a CA Supreme Court decision from heyday of degrowth era.

Mahon: yes

American Tower: no

/6

Mahon: yes

American Tower: no

/6

This split was of more theoretical than practical interest, because the CEQA carveout meant cities could delay projects indefinitely w/o worrying about deemed approvals.

Some (probably most) cities adopted convention of approving project & CEQA docs at same time.

/7

Some (probably most) cities adopted convention of approving project & CEQA docs at same time.

/7

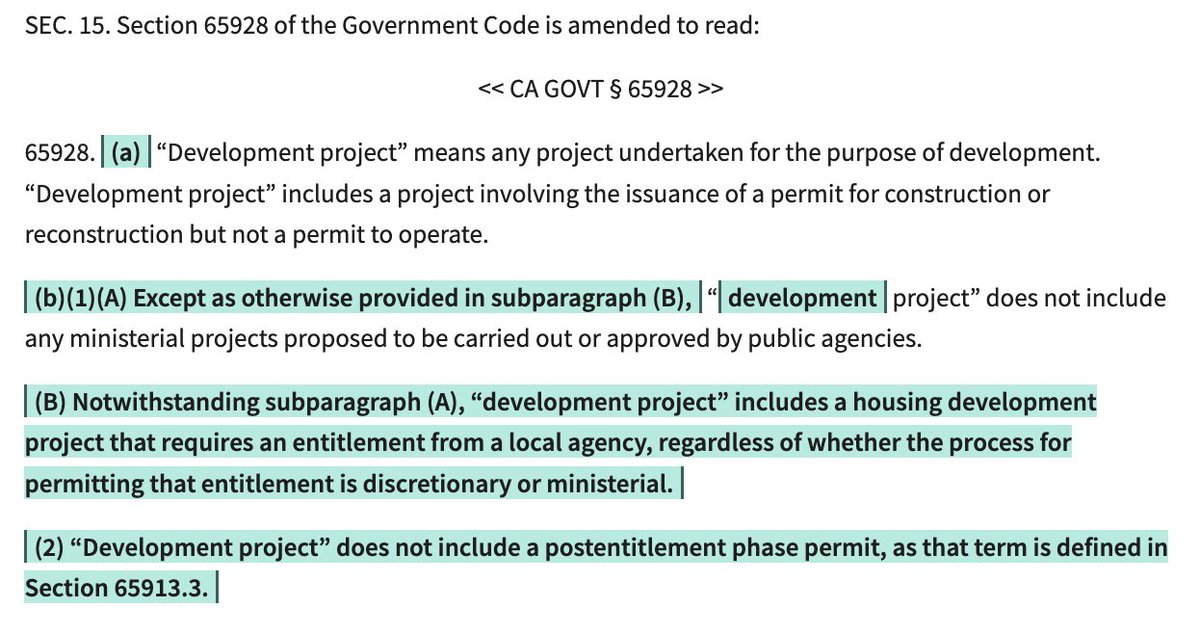

You might suppose that the PSA would at least have worked for ministerial projects -- which are not subject to CEQA, and for which the neighbors aren't entitled to a hearing under Horn.

But the Leg carved ministerial projects out of the PSA.

/8

But the Leg carved ministerial projects out of the PSA.

/8

Today, we're in a new world, thanks to major statutory reforms enacted in 2023 and 2025.

In 2023, the Leg passed AB 1633, which provides a remedy for CEQA delay on infill housing projects.

Here's my contemporaneous thread on AB 1633 & the PSA,

/9

In 2023, the Leg passed AB 1633, which provides a remedy for CEQA delay on infill housing projects.

Here's my contemporaneous thread on AB 1633 & the PSA,

/9

https://x.com/CSElmendorf/status/1712667038223839294

In 2025, the Leg passed AB 130, the blockbuster @BuffyWicks & @CAgovernor trailer bill, which carved most infill housing out of CEQA entirely.

AB 130 made important tweaks to the PSA, too.

/10

AB 130 made important tweaks to the PSA, too.

/10

First, it removed the PSA's exclusion for ministerial housing permits. Now they too will be "deemed approved" if city misses the deadline.

This is a big deal for cities that are subject to the ministerial-permitting penalty box of SB 35/423.

Looking at you, San Francisco.

/11

This is a big deal for cities that are subject to the ministerial-permitting penalty box of SB 35/423.

Looking at you, San Francisco.

/11

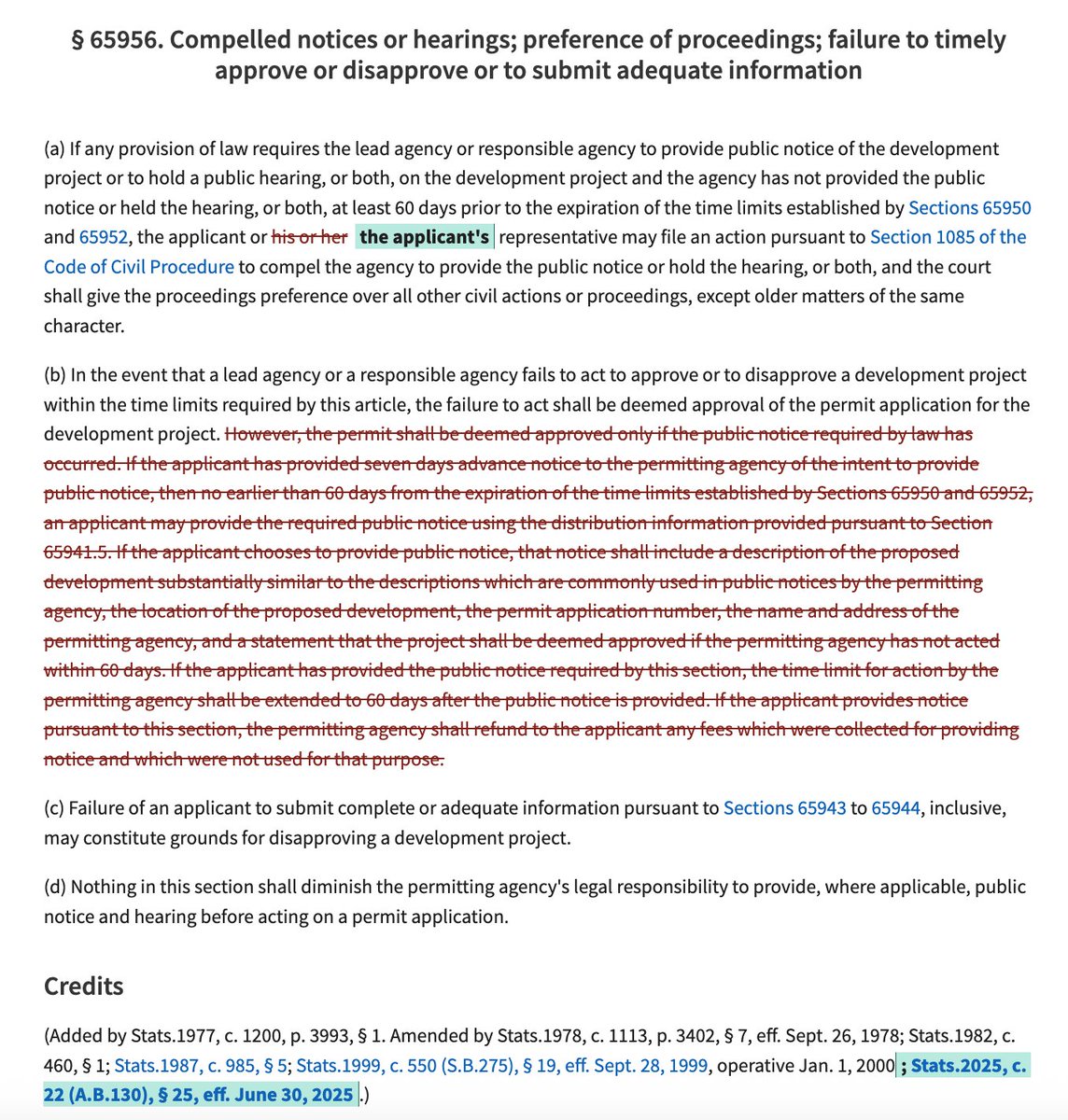

Second, AB 130 ditched the Leg's earlier due-process "fix," removing the stipulation that a project becomes deemed-approved only after any "public notice required by law."

(Self-help notice was repealed too.)

/12

(Self-help notice was repealed too.)

/12

In effect, the Leg said to the courts, "Decide whether Horn is still good law today."

My student @mimiminassians wrote a terrific paper arguing that Horn should be distinguished or overruled. Mandatory reading for CA land-use lawyers!

/13

My student @mimiminassians wrote a terrific paper arguing that Horn should be distinguished or overruled. Mandatory reading for CA land-use lawyers!

/13

https://x.com/CSElmendorf/status/1737556470332629208

Yet even assuming that the courts distinguish (as I expect) or overrule Horn, further leg tinkering will probably be needed before the PSA works as more than a negotiating tactic.

Two big problems remain.

/14

Two big problems remain.

/14

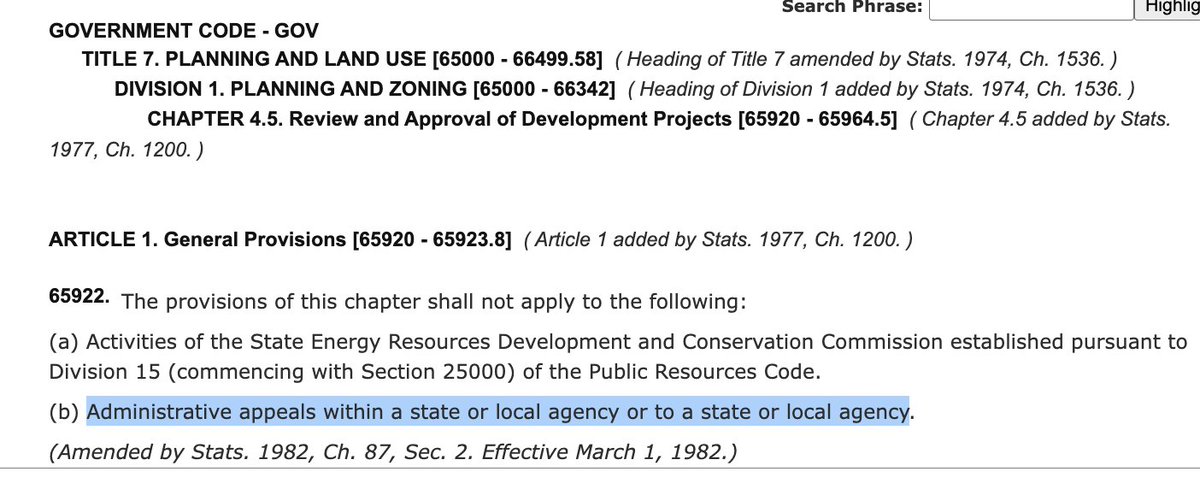

First, the PSA does not apply to "administrative appeals."

Many cities authorize de novo review of housing entitlements by city council or a board of permit appeals. This almost surely counts as an administrative appeal.

/15

Many cities authorize de novo review of housing entitlements by city council or a board of permit appeals. This almost surely counts as an administrative appeal.

/15

There's a plausible (not decisive) argument that a deemed-approved permit may be rejected or modified on internal appeal on same basis as a regularly issued permit...and that city council may take as long as it wants to hear the internal appeal.

/16

law.justia.com/cases/californ…

/16

law.justia.com/cases/californ…

If the PSA merely advances a project from a city's less-political decision-making body (planning department or commission) to the more-political one (city council), it won't accomplish very much.

/17

/17

Second, deemed-approved permits are subject to judicial review. A court is supposed to vacate the permit if the project wasn't approvable (i.e., violates an applicable objective standard).

That's fine in principle but a mess in practice.

/18law.justia.com/cases/californ…

That's fine in principle but a mess in practice.

/18law.justia.com/cases/californ…

E.g., when does the statute of limitations for filing a lawsuit start to run?

In Ciani, the court said the normal SOL applies but is tolled until project opponent has notice of the deemed approval.

Yet the deemed approval is something that happens by operation of law...

/19

In Ciani, the court said the normal SOL applies but is tolled until project opponent has notice of the deemed approval.

Yet the deemed approval is something that happens by operation of law...

/19

... it's not memorialized anywhere, and, as in this San Diego example, there may well be disputes between the city and the developer about whether it even occurred.

/20

.timesofsandiego.com/politics/2025/…

/20

.timesofsandiego.com/politics/2025/…

Second, what is the record on judicial review? By hypothesis, there was no public hearing or notice before the project was "deemed approved."

Does that mean neighbors may introduce new evidence in court? Is court to hold a trial de novo on whether project was approvable?

/21

Does that mean neighbors may introduce new evidence in court? Is court to hold a trial de novo on whether project was approvable?

/21

These problems are fixable if the Leg wants to make the PSA work. Will the new San Diego case prod the Leg to address them?

@DRand2024 @ceqalaw @nicholas_bagley @mnolangray @TimesofSanDiego @dillonliam

/end

@DRand2024 @ceqalaw @nicholas_bagley @mnolangray @TimesofSanDiego @dillonliam

/end

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh