I think we've let the damage that covid infections do to *linings* slip into the background of all the other problems that covid infections cause.

I think this may be a *big* problem.

I think this may be a *big* problem.

Across all of these, the pattern is the same: structural cell loss is followed by repair that restores structural continuity but not precision of purpose.

The tissue remains present, but its behaviour changes.

Function becomes uneven.

Symptoms emerge from loss of fine control

Function becomes uneven.

Symptoms emerge from loss of fine control

So there it is, making *everything else* worse, and causing plenty of its own problems.

And did I say...

They epithelial and endothelial damage is cumulative?

They epithelial and endothelial damage is cumulative?

A single infection may cause limited cell loss that is repaired well enough to restore basic function.

But repair is rarely perfect.

But repair is rarely perfect.

Small areas heal thinner.

Others heal stiffer.

Junctions are re-formed, but not always with the same precision.

On its own, that may cause few or no symptoms.

Others heal stiffer.

Junctions are re-formed, but not always with the same precision.

On its own, that may cause few or no symptoms.

With reinfections, the same surfaces are stressed again, the injury does not start from a clean baseline.

Each cycle increases the chance that repair shifts from replacement toward scarring, or from regulation toward rigidity.

Over time, this changes how the tissue behaves even if it still looks intact.

Like a waterproof jacket that's just... no longer waterproof.

Because epithelial and endothelial cells form continuous sheets, damage does not need to be extensive to matter. Patchy loss creates uneven repair.

How much of a balloon needs to break for it to pop?

I have spent hours and hours this autumn supporting a young professional whose artery ruptured after they had a covid infection.

How much of an artery needs to fail for you to have a rupture?

How much of an artery needs to fail for you to have a rupture?

Like I said, patchy loss creates uneven repair. Some areas remain flexible and responsive.

Others become leaky or stiff.

The system still functions, but less smoothly.

Reserve is lost.

Tolerance to stress drops.

Symptoms appear earlier and last longer after each insult.

The system still functions, but less smoothly.

Reserve is lost.

Tolerance to stress drops.

Symptoms appear earlier and last longer after each insult.

This cumulative process also partly explains why later infections can feel different from earlier ones. The pathogen may be the same, but the tissue it encounters is not.

Repair pathways are more easily tipped into fibrosis.

Inflammation spreads more readily because containment is weaker.

Recovery takes longer because the structure being repaired is already altered.

It also partly explains why other infections hit so hard straight after Covid.

The castle walls are broken.

It even explains why some infections are possible at all.

Things that should never be able to get past linings now can.

The castle walls are broken.

It even explains why some infections are possible at all.

Things that should never be able to get past linings now can.

Importantly, this is not about damage endlessly adding up cell by cell, it is about architecture drifting over time. Each repair slightly reshapes the surface.

After enough cycles, the tissue behaves differently as a whole. That is why the effects are often delayed, diffuse, hard to pin to any single event, and so hard to spot and pull together as one single problem.

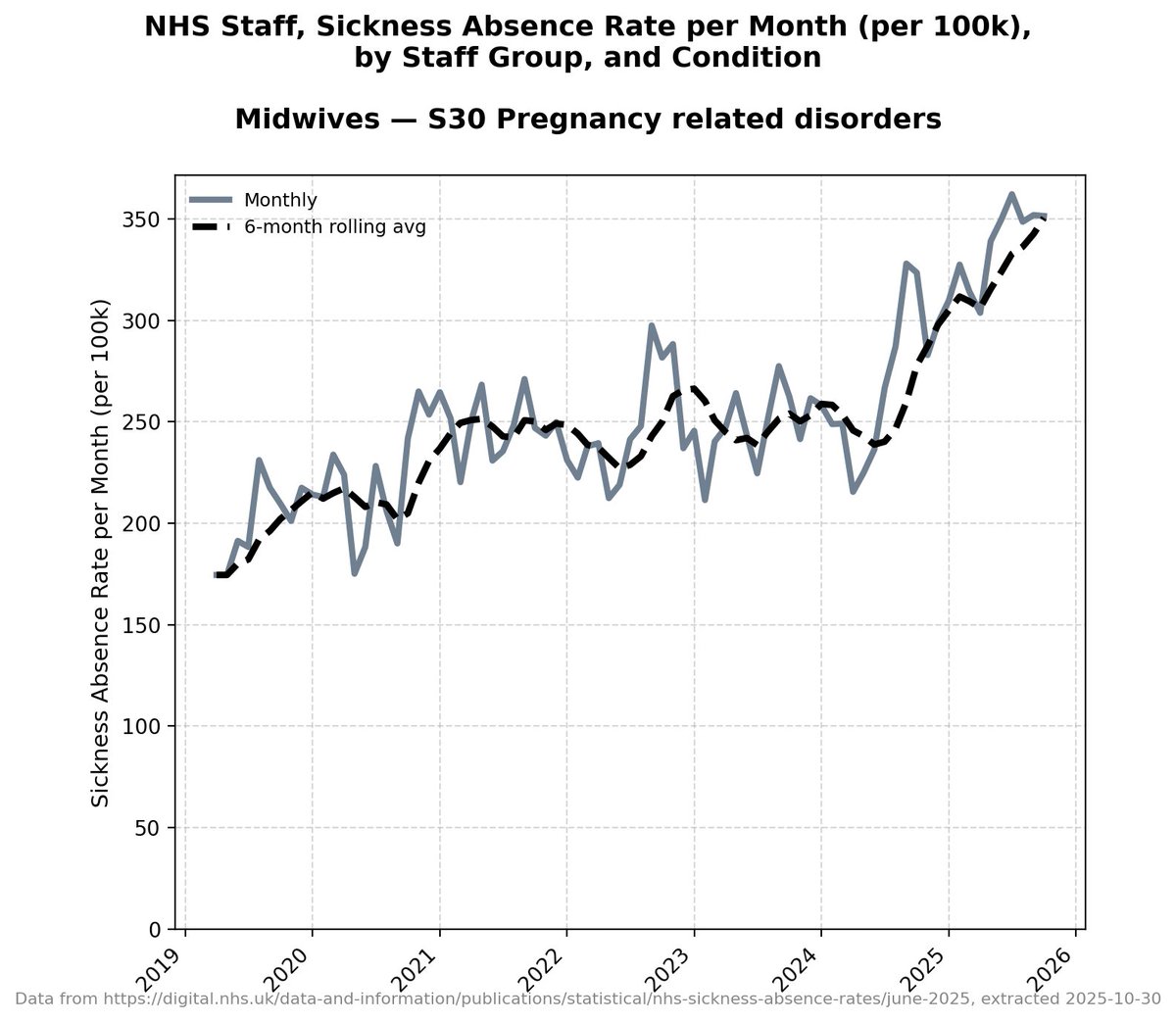

Now... this all adds in to the way covid infection affects different age groups differently.

Different age groups are at different stages in immune capacity and adaptability.

And different stages of metabolism.

Different age groups are at different stages in immune capacity and adaptability.

And different stages of metabolism.

So in children and young people, epithelial and endothelial tissues generally repair quickly. Cell turnover is high, blood supply is good, and scarring is less likely after a single injury.

You're less likely to see the effects of leakiness and stiffness in kids yet.

You're less likely to see the effects of leakiness and stiffness in kids yet.

Yet.

That gives a lot of resilience. But repeated infections still matter.

Each episode places demands on repair systems that are still developing. Most recover well, but a small minority may be left with subtle changes in regulation or sensitivity that only become obvious later, when demands increase.

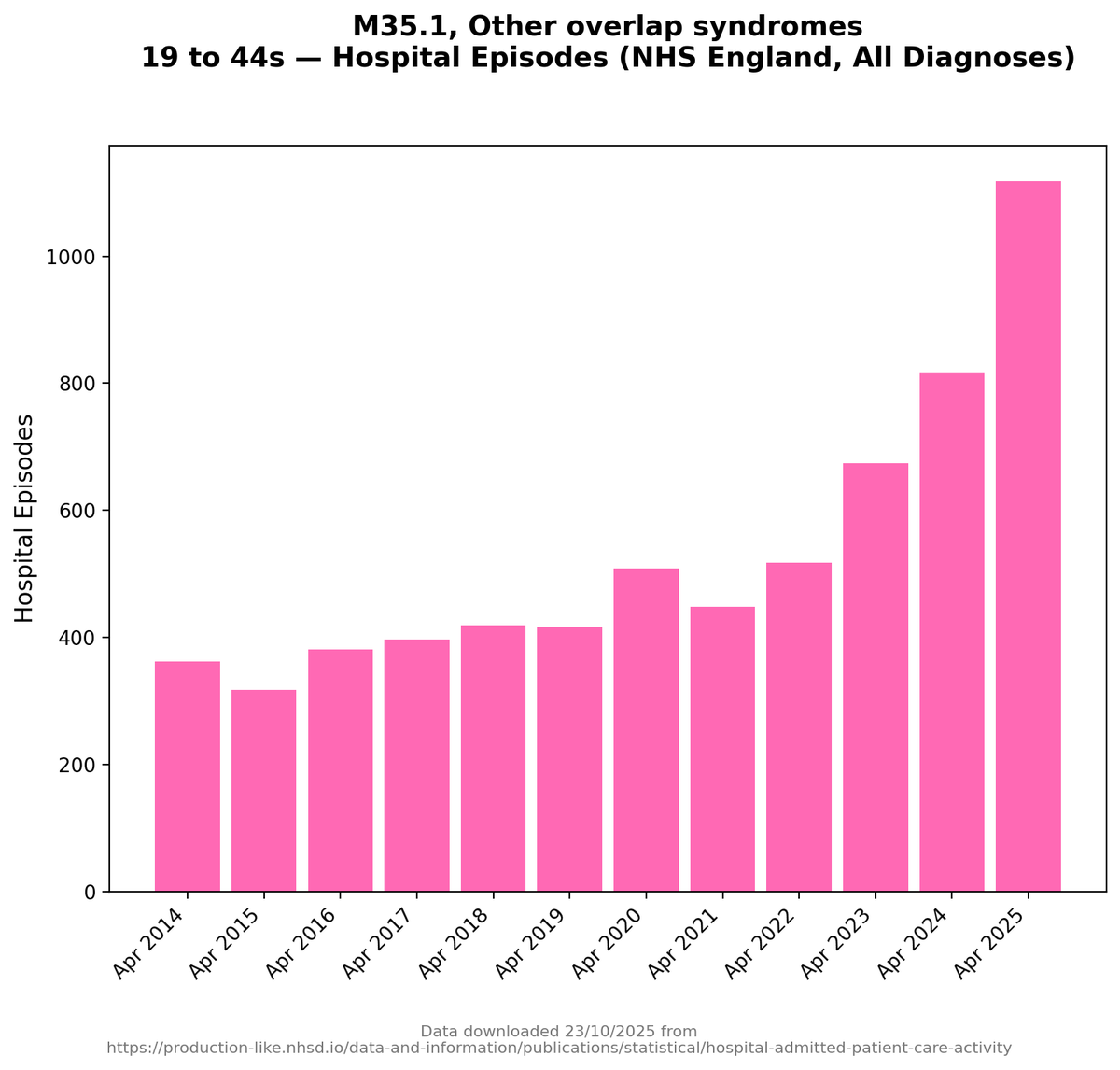

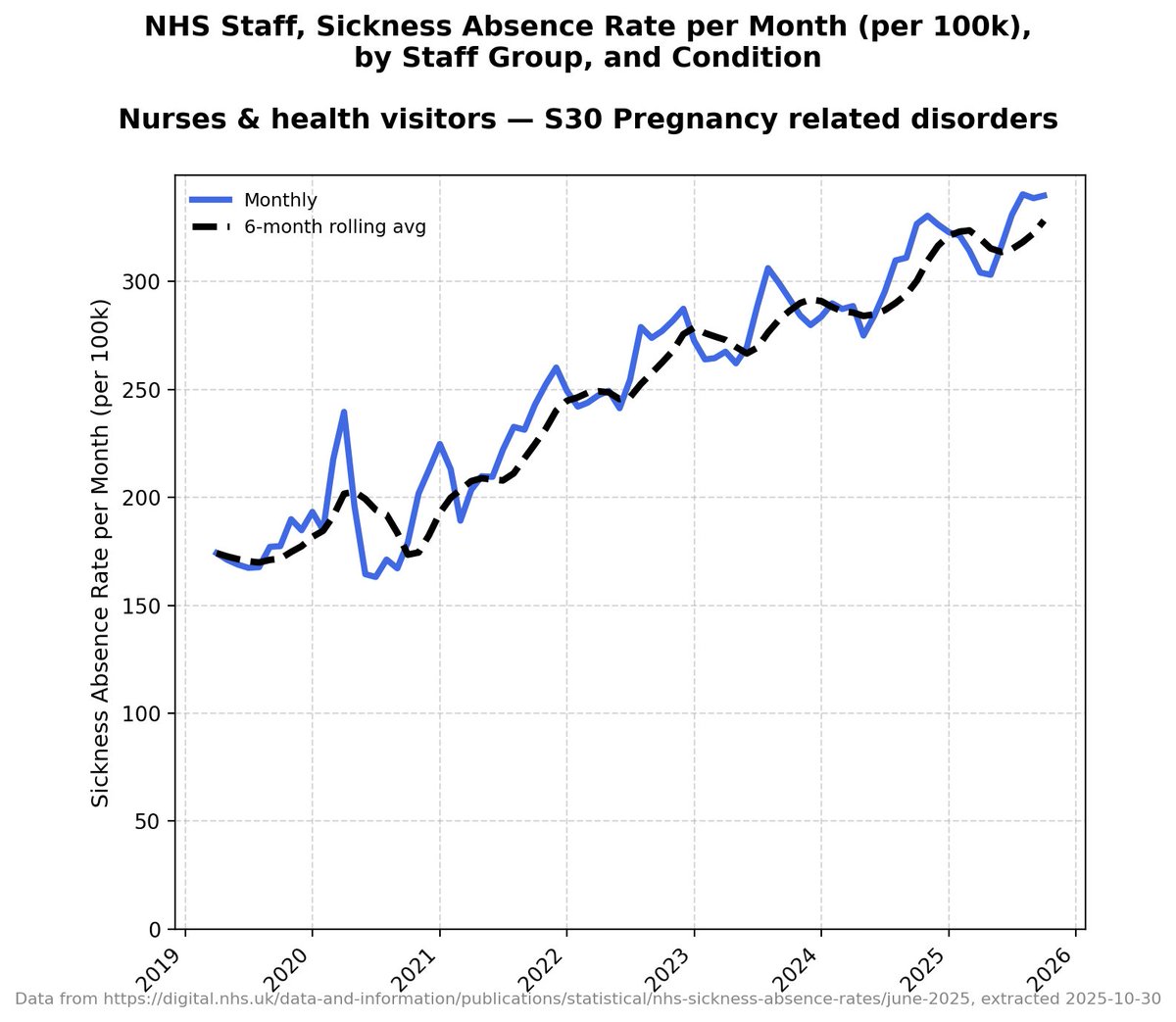

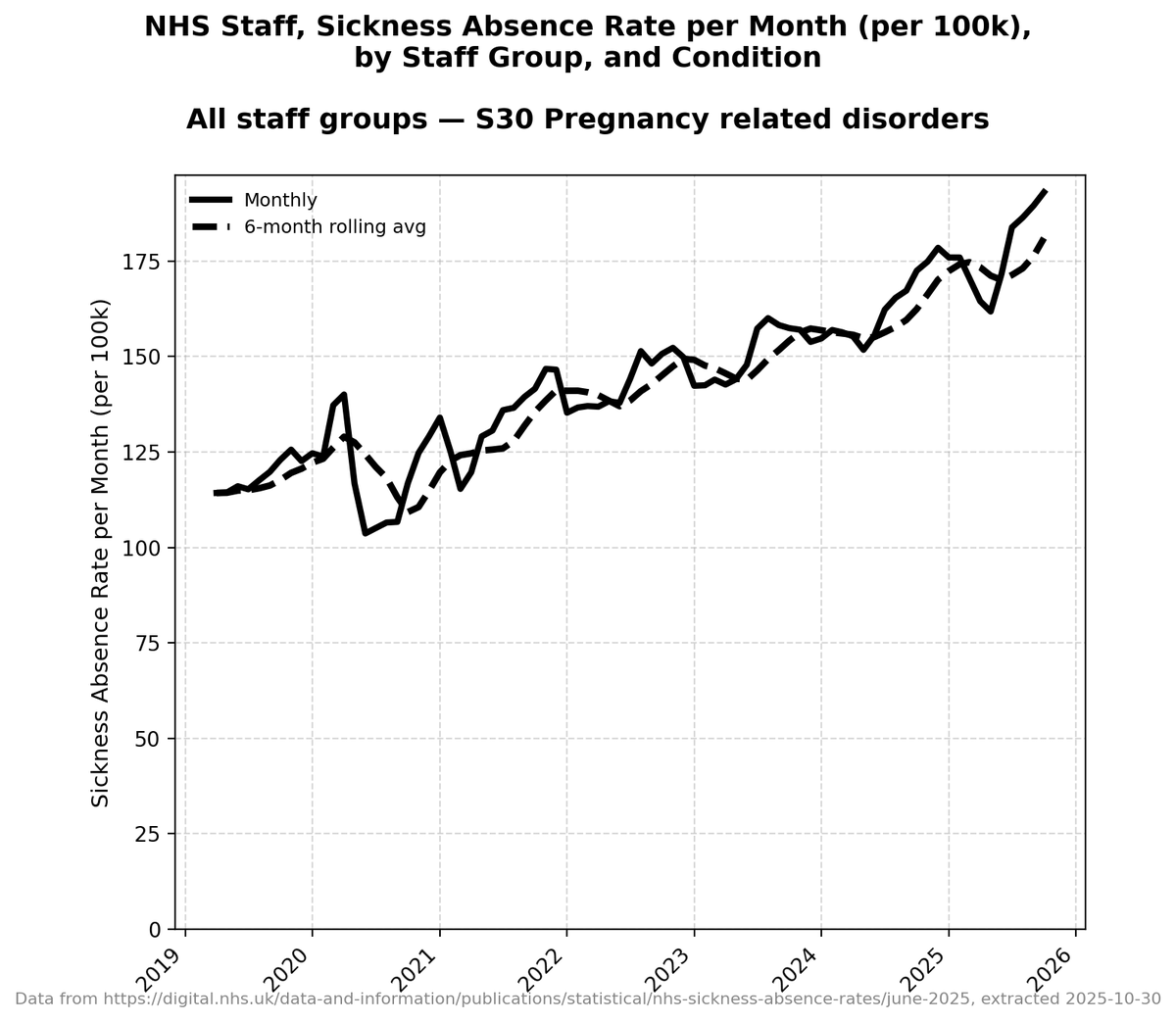

That's reflected in the charts.

The conditions affected by lining damage aren't showing up so much in kids yet.

The conditions affected by lining damage aren't showing up so much in kids yet.

Yet.

In young adults, repair is still effective, but less forgiving. Barriers usually reseal, yet repair is more variable. Some areas heal well, others less precisely. Reinfections land on tissue that is no longer pristine.

Symptoms may be intermittent. Recovery may feel slower than it used to be. People notice reduced tolerance for stress, exercise, or illness, even though tests often look normal.

In midlife, cumulative effects become clearer. Repair is slower. Fibrotic responses are more likely. The balance tips more easily from replacement toward scarring. Small losses of reserve start to matter.

Systems still work, but with less margin. This is where people begin to see clustering of problems: lungs and heart rhythm, gut and brain, skin and nerves. Not failure yet necessarily, but reduced adaptability.

In older adults, the same processes are amplified. Structural cell turnover is slower. Repair pathways favour sealing and stiffness over fine control.

Pre-existing scarring becomes a scaffold for further dysfunction.

This is where I'm seeing most of the accelerated damage in the part of my work that involves supporting people through ill health.

Reinfections are less well tolerated, not because the infection is worse, but because the tissue being repaired is already altered. Recovery is longer, and baseline function may not fully return.

Each episode places demands on repair systems that are still developing. Most recover, but a small minority may be left with subtle changes in regulation or sensitivity that only become obvious when demands increase.

And that's often the point of crisis.

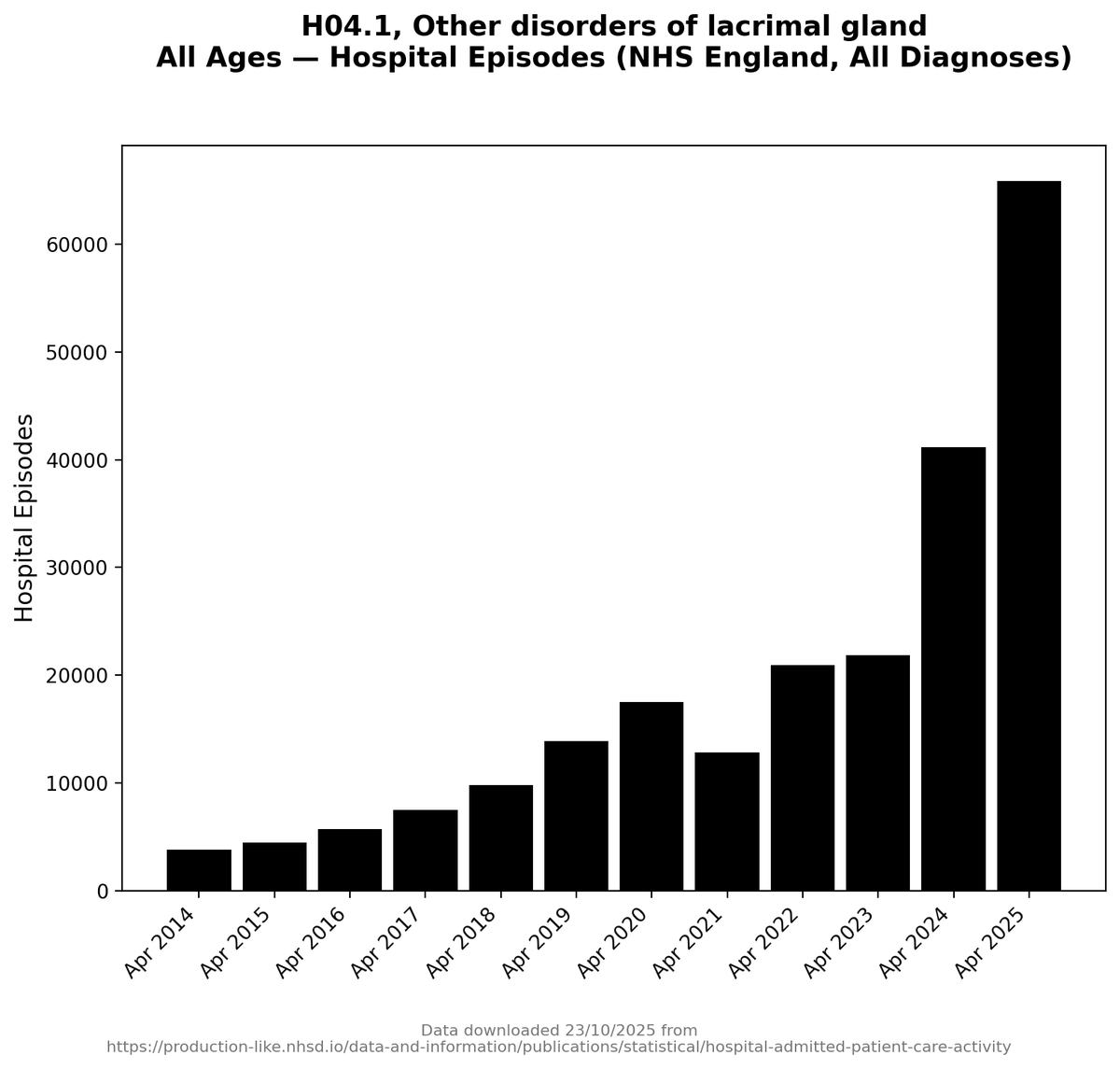

I was going to do a separate thread on how this all interacts with conditions like Sjögren's Disease (and still will do), but I think it's worth putting some of it here.

Sjogren's sits right at the intersection of barrier failure, immune dysregulation, and poor repair.

It is usually described as an autoimmune disease affecting salivary and tear glands, but that description undersells what is actually going on.

At its core, Sjogren's is a condition where epithelial surfaces that should stay moist, protected, and regulated lose their integrity and become chronically inflamed.

The earliest and most obvious features are classic barrier problems: dry eyes and dry mouth reflect failure of epithelial linings and glandular interfaces that normally regulate fluid secretion.

Once those surfaces dry out and become inflamed, they are more vulnerable to irritation, infection, and nerve sensitisation.

The symptoms feel *local* - like dry eyes - but the underlying problem is *loss of epithelial stability*.

What makes Sjogren's especially relevant here is that it does not stay confined to glands.

Many people develop problems involving joints, lungs, kidneys, nerves, blood vessels, skin, and the brain.

Sjogren's also gives you increased risk of several other serious secondary conditions.

These are often treated as separate complications, but they follow a familiar pattern: surfaces and interfaces become inflamed or leaky, immune activity escapes its normal boundaries, and repair is incomplete or maladaptive.

Fibrosis plays a role too.

In Sjogren's, chronic inflammation can lead to scarring in salivary glands, lung tissue, and kidneys.

In Sjogren's, chronic inflammation can lead to scarring in salivary glands, lung tissue, and kidneys.

That scarring stiffens tissue, reduces function, and locks in symptoms even when the overt stages of inflammation are fluctuating.

In sport we say "form is temporary, class is permanent".

Tissue damage is like that.

Tissue damage is like that.

The disease shifts from active attack to structural damage, which is harder to reverse and less responsive to anti-inflammatory treatment alone.

I've been through the whole process of 'realising something is slightly wrong', 'realising it may be necessary to talk to a doctor', 'realising something is badly wrong', 'realising doctors can't help', 'realising this is it' with a close family member with Sjogren's.

I write about this from painful experience.

The story we experienced also highlights how Sjogren's symptoms cluster across systems that are supposed to be unrelated.

Dry eyes appear alongside joint pain.

Lung involvement alongside fatigue and brain fog.

Neuropathic pain alongside gut and bladder symptoms.

These clusters make more sense when you think in terms of *shared epithelial and endothelial vulnerability* rather than isolated organ failure.

In that sense, Sjogren's is a clear, established example of what happens when barrier systems fail, immune control loosens, and repair goes wrong.

It shows how a condition can begin at surfaces and interfaces, then ripple outward into a multisystem disease without ever needing a single dramatic failure of a membrane or lining, or even an obvious site of damage.

And the sad news is that there are some very concerning rises in conditions that are *indicators* of Sjogren's.

That's going to come in a separate thread - I think it's *very* serious.

That's going to come in a separate thread - I think it's *very* serious.

Without going into too much depth on all of them, I think there are several other conditions like Sjogren's that are also ones to keep a very close eye on:

Systemic sclerosis and scleroderma

A disease of epithelial and endothelial injury followed by fibrosis.

Starts at skin and blood vessels, then affects lungs, gut, kidneys, and heart through stiffening and barrier dysfunction.

A disease of epithelial and endothelial injury followed by fibrosis.

Starts at skin and blood vessels, then affects lungs, gut, kidneys, and heart through stiffening and barrier dysfunction.

I had initially thought that scleroderma was one condition that wasn't being made worse by covid infection, but recently I've had reason to suspect it needs watching.

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Immune attack targets interfaces such as blood vessels, skin, kidneys, joints, and the blood–brain barrier. Symptoms move between systems *depending on which boundaries fail*.

Immune attack targets interfaces such as blood vessels, skin, kidneys, joints, and the blood–brain barrier. Symptoms move between systems *depending on which boundaries fail*.

Mixed connective tissue disease

An overlap condition by definition. Features from lupus, scleroderma, and myositis combine, reflecting widespread interface and vascular involvement rather than single-organ failure.

An overlap condition by definition. Features from lupus, scleroderma, and myositis combine, reflecting widespread interface and vascular involvement rather than single-organ failure.

Antiphospholipid syndrome

Primarily an endothelial disorder. Abnormal clotting arises because vascular interfaces behave incorrectly, affecting brain, placenta, kidneys, lungs, and skin.

Primarily an endothelial disorder. Abnormal clotting arises because vascular interfaces behave incorrectly, affecting brain, placenta, kidneys, lungs, and skin.

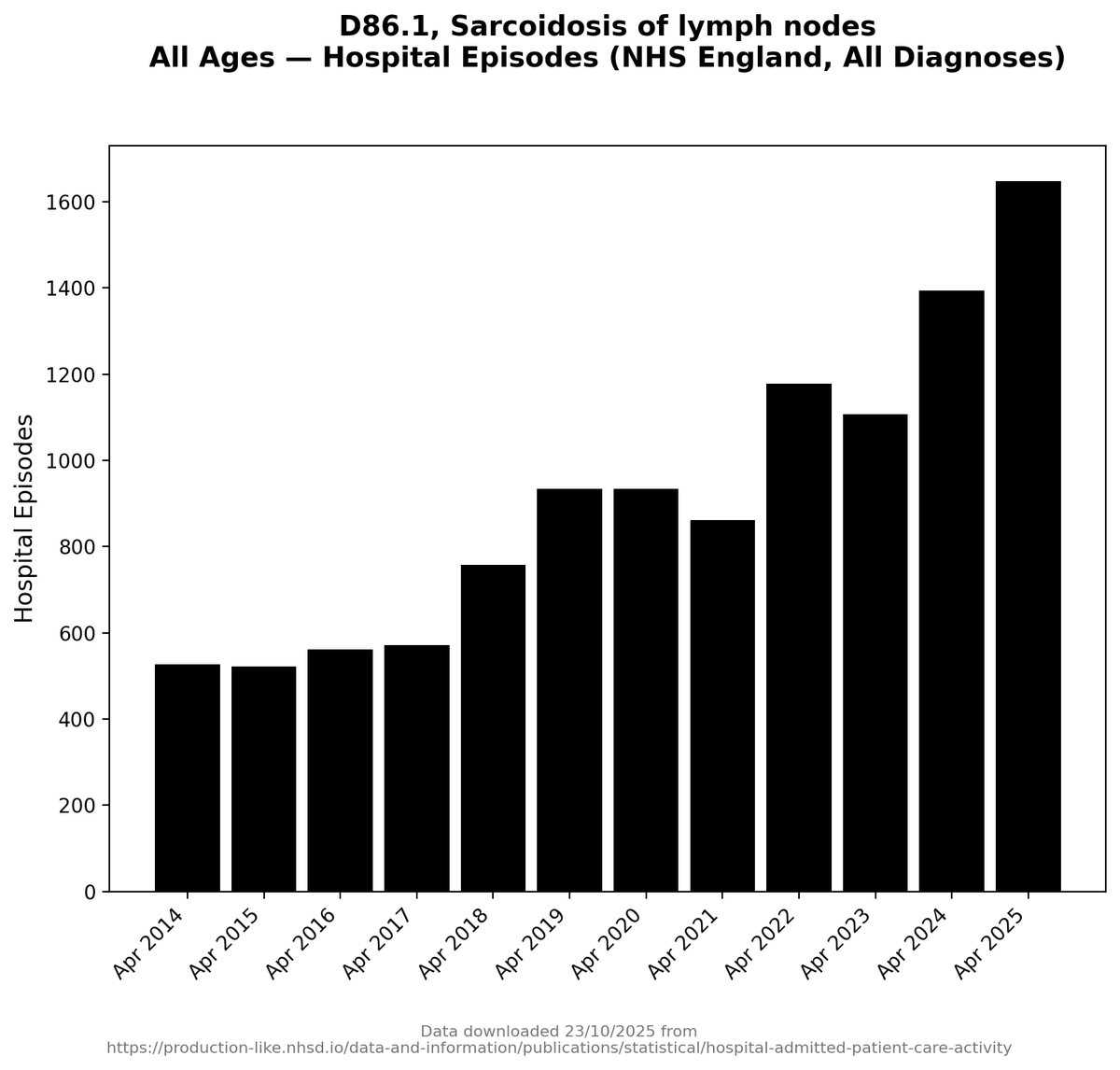

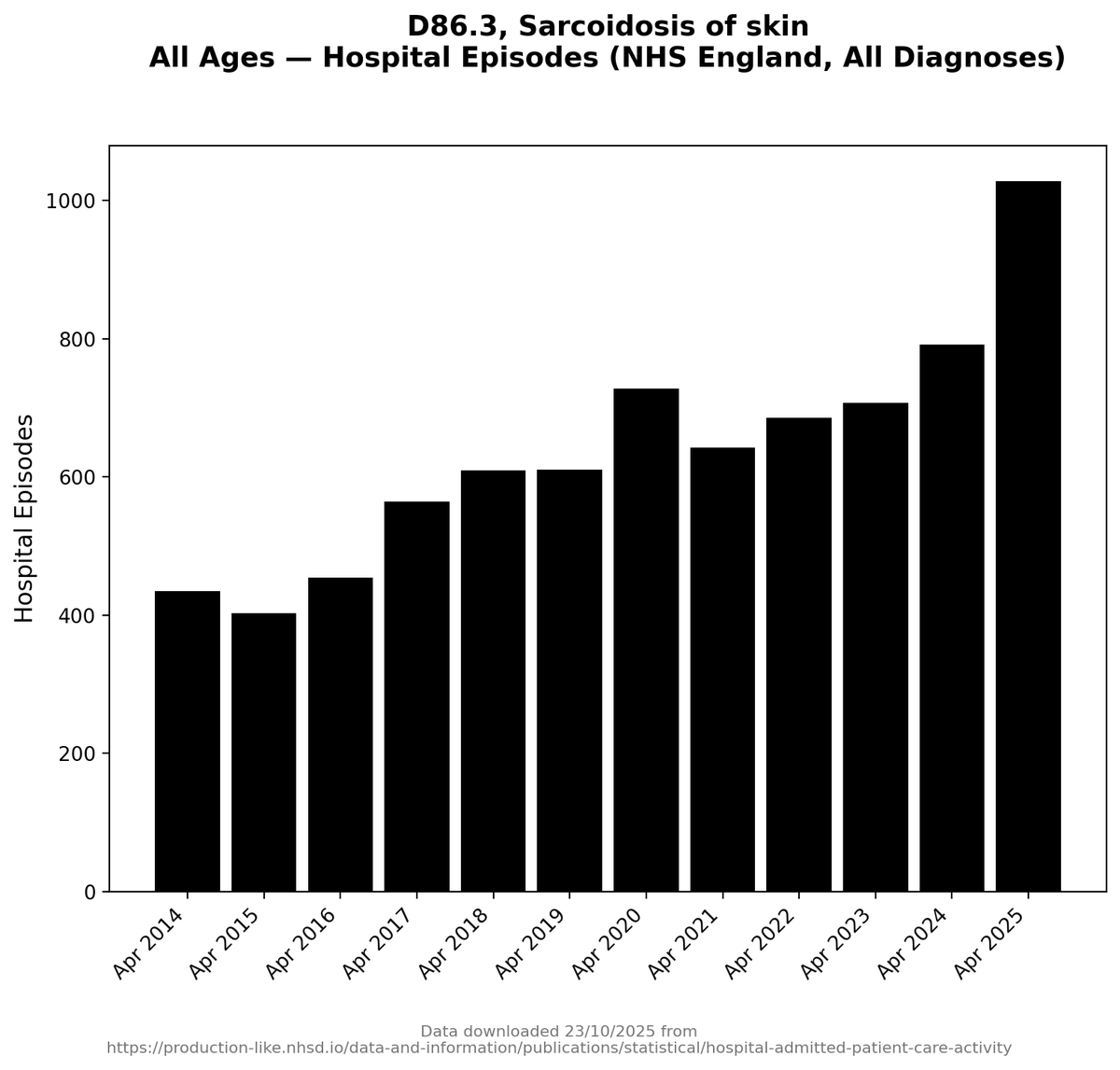

Sarcoidosis

Granulomas form at tissue interfaces, especially in lungs, lymph nodes, skin, eyes, and heart. The disease respects no single organ boundary.

Granulomas form at tissue interfaces, especially in lungs, lymph nodes, skin, eyes, and heart. The disease respects no single organ boundary.

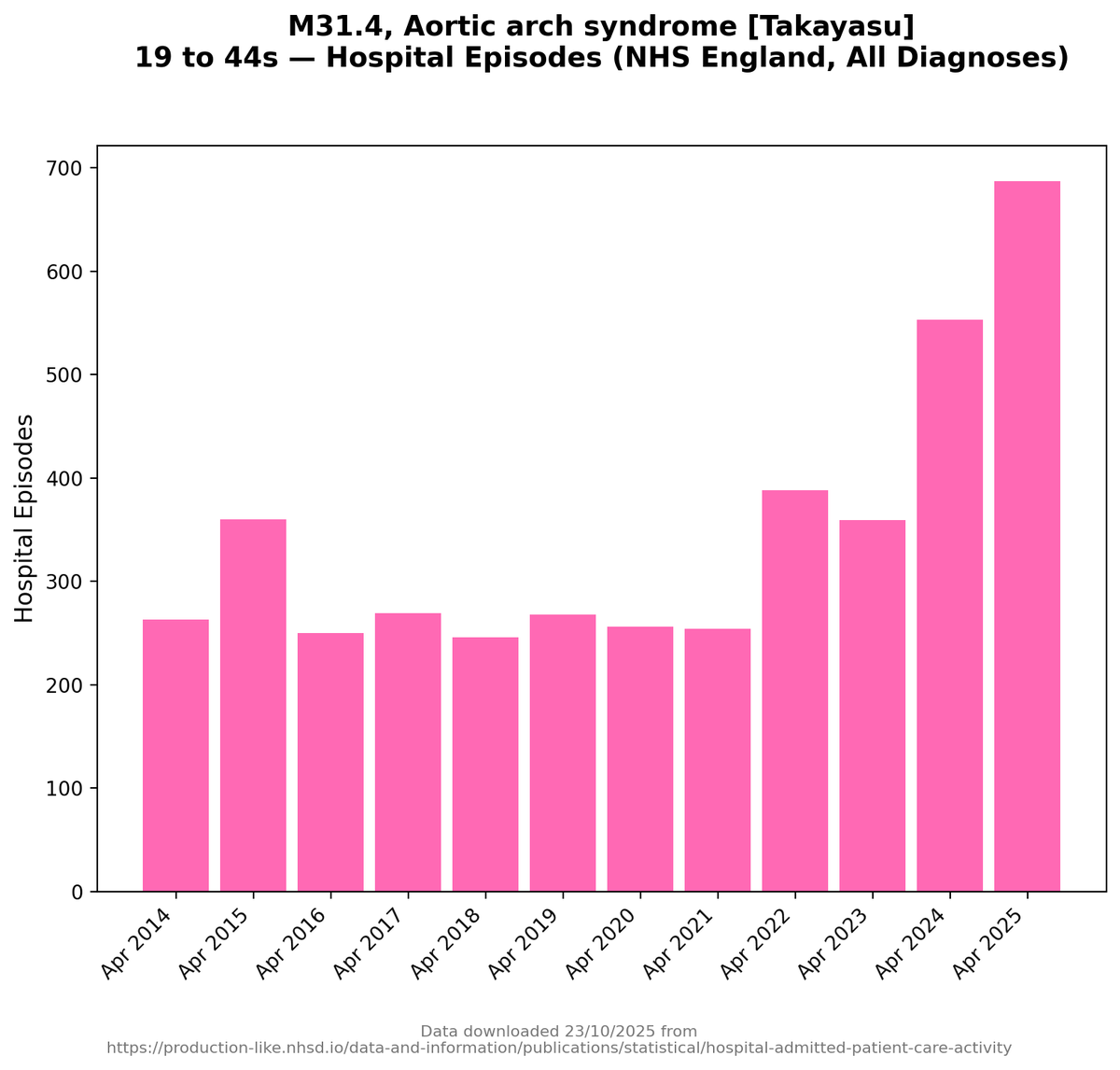

Vasculitis syndromes

Inflammation targets blood vessel walls, disrupting the interface between circulation and tissue. Effects appear wherever vessels supply organs, including nerves, kidneys, lungs, and skin.

Inflammation targets blood vessel walls, disrupting the interface between circulation and tissue. Effects appear wherever vessels supply organs, including nerves, kidneys, lungs, and skin.

Inflammatory bowel disease *with extraintestinal manifestations*

Begins at the gut lining but frequently involves joints, skin, eyes, liver, and blood vessels, reflecting shared epithelial and immune pathways.

Begins at the gut lining but frequently involves joints, skin, eyes, liver, and blood vessels, reflecting shared epithelial and immune pathways.

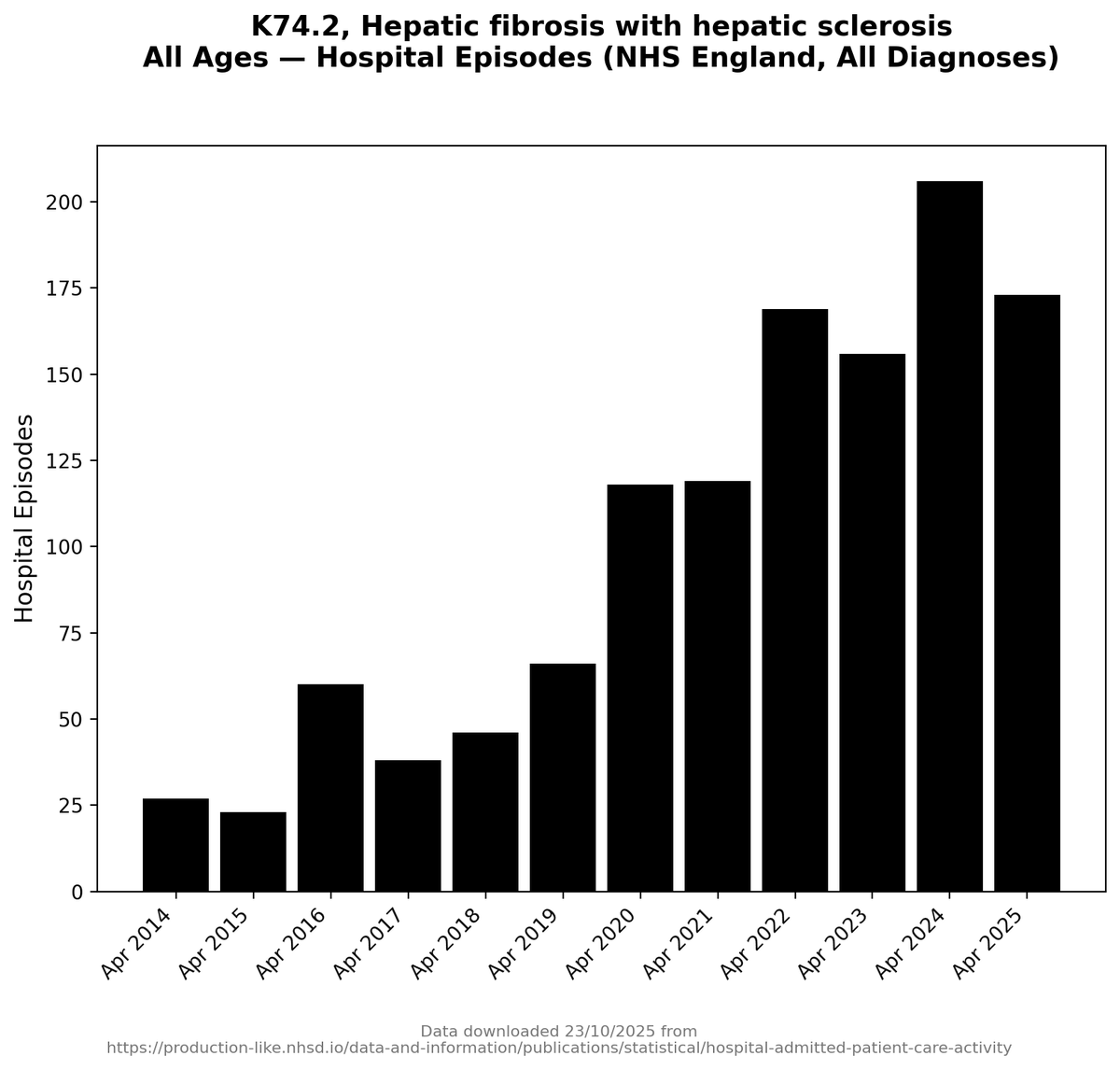

Primary biliary cholangitis

Targets epithelial linings of bile ducts, then extends systemically through immune and vascular effects, often clustering with Sjogren’s.

Targets epithelial linings of bile ducts, then extends systemically through immune and vascular effects, often clustering with Sjogren’s.

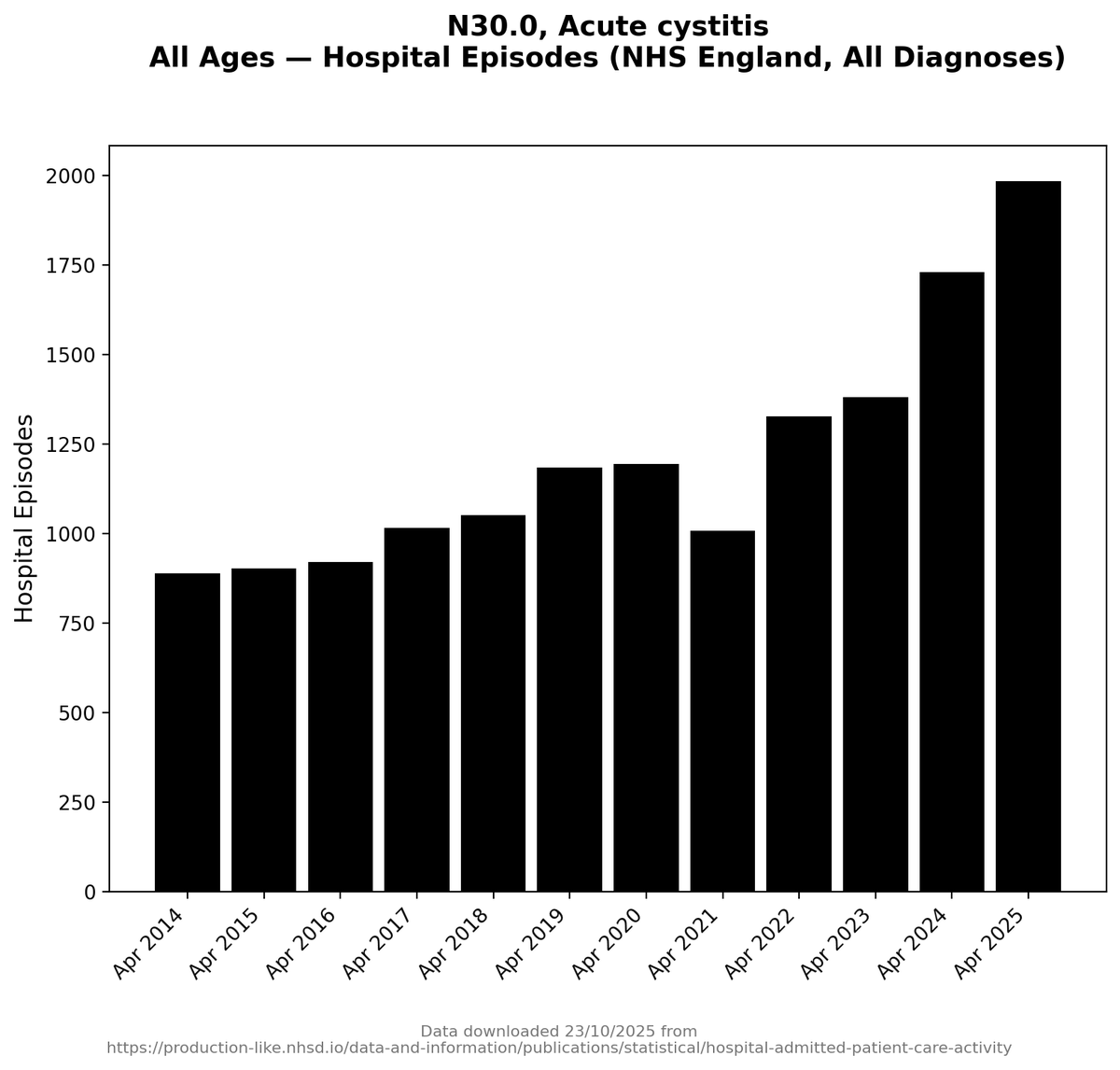

Interstitial cystitis / bladder pain syndrome

A urothelial barrier disorder with immune and nerve involvement. Often overlaps with gut, pelvic, and autoimmune conditions.

A urothelial barrier disorder with immune and nerve involvement. Often overlaps with gut, pelvic, and autoimmune conditions.

Endometriosis

Misplaced epithelial-like tissue breaches anatomical boundaries, provoking inflammation and fibrosis across pelvic organs, nerves, and bowel.

Misplaced epithelial-like tissue breaches anatomical boundaries, provoking inflammation and fibrosis across pelvic organs, nerves, and bowel.

IgG4-related disease

A systemic fibro-inflammatory condition affecting glands, ducts, vessels, and organs at interfaces. Characterised by swelling, scarring, and loss of normal compartmentalisation.

A systemic fibro-inflammatory condition affecting glands, ducts, vessels, and organs at interfaces. Characterised by swelling, scarring, and loss of normal compartmentalisation.

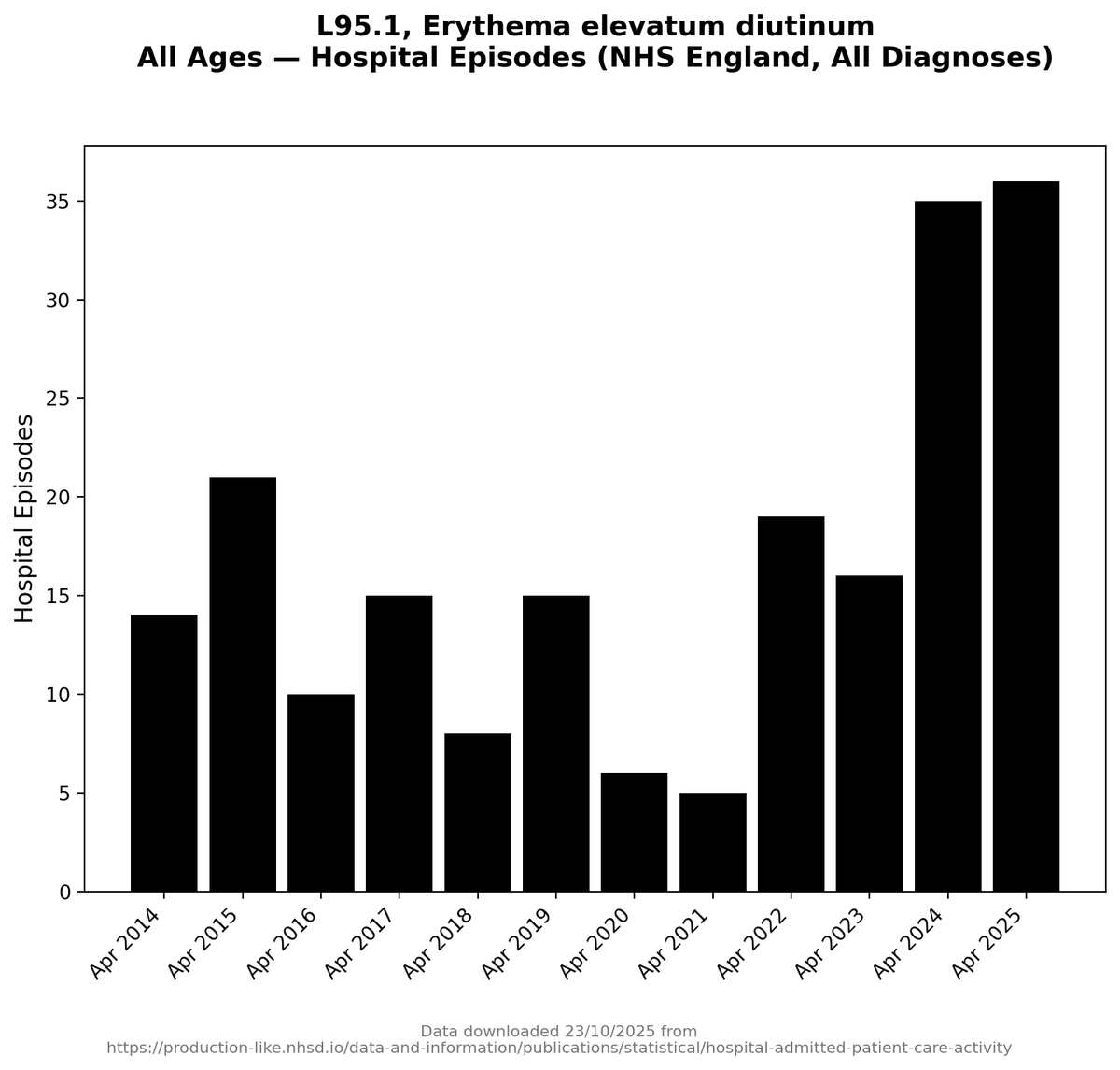

erythema elevatum diutinum...

It’s a chronic small-vessel vasculitis of the skin

Low numbers... but not as low as they used to be.

It’s a chronic small-vessel vasculitis of the skin

Low numbers... but not as low as they used to be.

There is often a *long* gap between problems beginning at barriers and interfaces, and anyone recognising that something is wrong.

Early barrier dysfunction is quiet.

Early barrier dysfunction is quiet.

They produce vague symptoms, shifting discomfort, and problems that come and go. Nothing dramatic enough to point clearly to one organ or one diagnosis. At this stage, the body is already struggling, but it is able to compensate.

When a person does seek help, the way medicine is organised shapes what happens next.

Doctors do not approach symptoms by asking whether epithelial or endothelial systems are failing.

Doctors do not approach symptoms by asking whether epithelial or endothelial systems are failing.

They work organ by organ:

Eyes go one way.

Joints another.

Gut symptoms another.

Each problem is approached in isolation.

Eyes go one way.

Joints another.

Gut symptoms another.

Each problem is approached in isolation.

Diagnosis then takes time because these conditions rarely announce themselves cleanly.

Tests are often normal early on.

You can't see damage on imaging until long after it appears as symptoms.

Blood markers fluctuate.

Tests are often normal early on.

You can't see damage on imaging until long after it appears as symptoms.

Blood markers fluctuate.

Many of these diseases are diagnoses of exclusion... which means other things have to be ruled out first.

*That process alone can take years*.

*That process alone can take years*.

Even once suspicion arises, confirmation is slow. Specialists are involved one at a time.

Referrals take months because they're not always urgent.

Referrals take months because they're not always urgent.

In the meantime, symptoms spread and deepen, not because the disease is fast, but because barrier failure and poor repair are still there in the background as the root of the whole problem.

So any rise in the conditions comes long after a rise in the problems that the conditions cause.

So, I think, the worst of all this is yet to come.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh