Very interesting result! What struck me most: nobody picked “depends”. I think that’s the right answer, but the question is, of course, "on what". To answer this, let's start with some general thoughts about the role of voters and interst groups in policymaking.

https://twitter.com/edenhofer_jacob/status/2012249546110202203

Simplifying crudely, think of both as "principals" that can impose political losses on a policymaker when (s)he deviates from their "bliss point", their ideal.

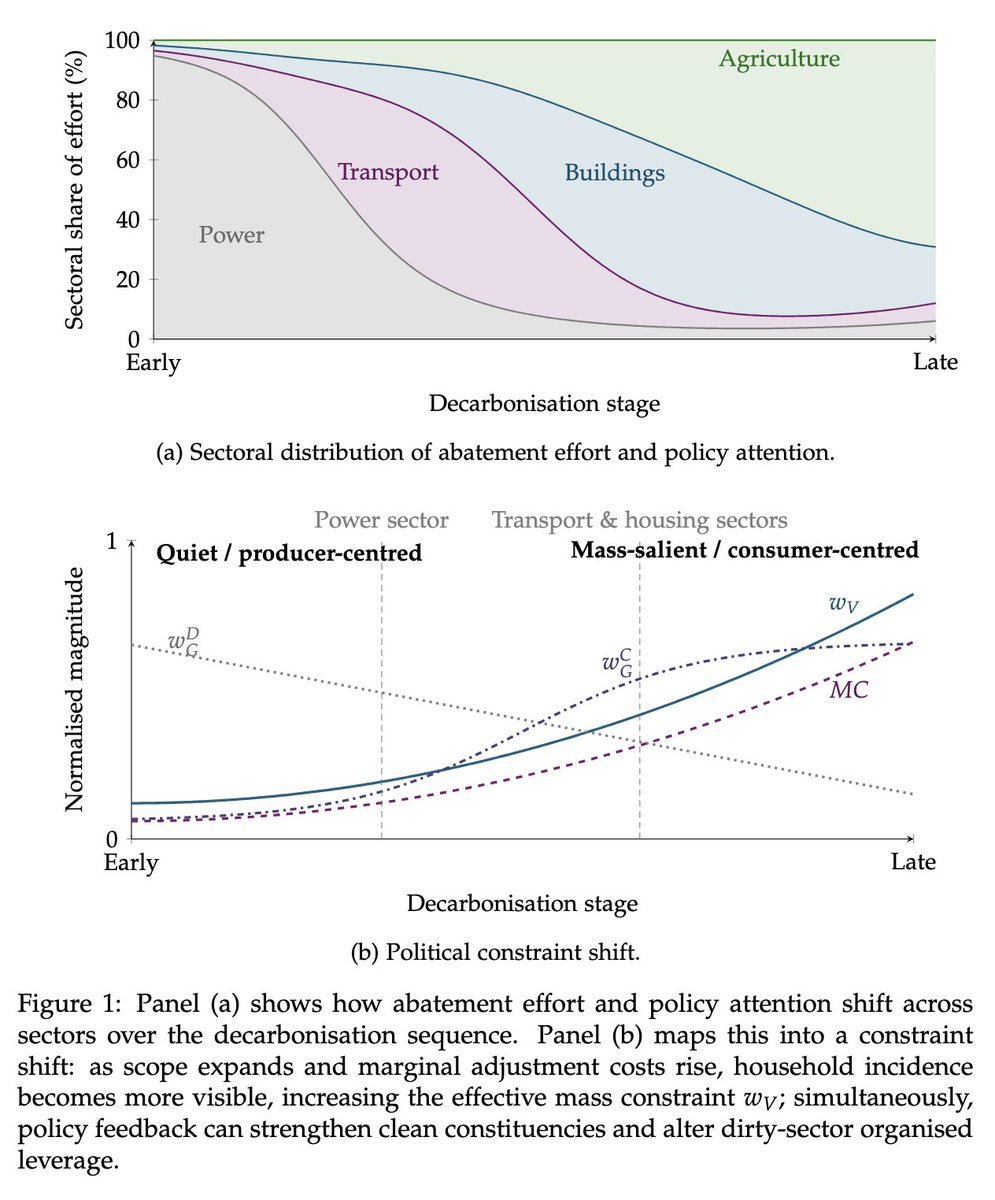

In climate policy, two forces change which constraint binds as decarbonisation deepens:

1. Rising marginal adjustment

In climate policy, two forces change which constraint binds as decarbonisation deepens:

1. Rising marginal adjustment

costs as stringency increases (low-hanging fruit are reaped).

2. Cost incidence visibility / attribution: whether households/voters experience costs as direct, frequent, and clearly attributable to some climate policy (e.g. a carbon tax).

Now add an empirical

2. Cost incidence visibility / attribution: whether households/voters experience costs as direct, frequent, and clearly attributable to some climate policy (e.g. a carbon tax).

Now add an empirical

regularity: many rich democracies have, roughly speaking, pursued the following sequence. Early abatement/policy effort: power sector.

Later: transport + buildings/housing.

Later still (often): agriculture, heavy industry, land-use.

Why does this matter? Because policies

Later: transport + buildings/housing.

Later still (often): agriculture, heavy industry, land-use.

Why does this matter? Because policies

targeted at the power sector have some rather specific characteristics. The are:

- they are technically complex and implementation-heavy (markets, permitting, grid, investment),

- producer-centred (concentrated stakes; organised actors -> can be bought off via exemptions or free

- they are technically complex and implementation-heavy (markets, permitting, grid, investment),

- producer-centred (concentrated stakes; organised actors -> can be bought off via exemptions or free

allocations at relatively moderate costs),

- the costs for households, albeit not insignificant, can often be diffused quiet effectively (both geographically and temporally); they also reach voters via pass-through, which makes attribution more difficult.

The result: early

- the costs for households, albeit not insignificant, can often be diffused quiet effectively (both geographically and temporally); they also reach voters via pass-through, which makes attribution more difficult.

The result: early

climate policy was largely (!) "quiet politics" a la Culpepper. I say "largely" because public opinion wasn't irrelevant. Even in early phases, green parties and NGOs mattered as salience entrepreneurs. Specifically, their presence entailed a threat

cambridge.org/core/books/qui…

cambridge.org/core/books/qui…

for governments: if you pander too much to dirty interest groups, then we will raise the salience of that deviation from public opinion and you will suffer political losses. Importantly, the incentive to politicise is -- perhaps somewhat paradoxically -- greater for those

parties that have a low chance of being in government in the future (as was the case for many green parties). The reason is that, when you are in government, you need the powerful interest groups to cooperate (so that they share information and don't obstruct your every turn).

But they won't be particularly cooperative if you have irked them in the previous period by politicising their anti-majoritarian skullduggery (see above). That threat is of course only credible when politicisation falls on fertile soil: some receptive pro-climate sentiment.

Final caveat: such threats matter mostly for overall ambition (targets, packages, commitments), rather than the specifics of policy design (e.g. car standards or the rules for the allocation of free permits).

Such salience entrepreneurs also matter in another way. By

Such salience entrepreneurs also matter in another way. By

providing incentives for some climate policy and cover for pro-climate bureaucrats, they also enable governments to implement policies that reconfigure the interest group environment (e.g. feed-in tariffs that strengthen the renewables lobby). Early policies can thus

build clean-sector constituencies that later lobby for ambition: the IG environment is, to some extent, endogenous to policy.

As we move beyond the power sector, it becomes much more difficult to hide costs from consumers/voters.

Transport + housing involve choices people make

As we move beyond the power sector, it becomes much more difficult to hide costs from consumers/voters.

Transport + housing involve choices people make

constantly (driving, heating, renovating). Costs become more visible and attributable.

So, at higher stringency, voters “matter more” because distributional conflict and attribution become harder to avoid. This changes the political problem from tinkering with the design of

So, at higher stringency, voters “matter more” because distributional conflict and attribution become harder to avoid. This changes the political problem from tinkering with the design of

policy instruments to creating a durable coalition.

This is where compensation and pork-barrel politics become pivotal. If household incidence is visible, governments need to answer: who pays, when, and for what? See my brief with @fgenovese__.

politicscentre.nuffield.ox.ac.uk/media/zdubebua…

This is where compensation and pork-barrel politics become pivotal. If household incidence is visible, governments need to answer: who pays, when, and for what? See my brief with @fgenovese__.

politicscentre.nuffield.ox.ac.uk/media/zdubebua…

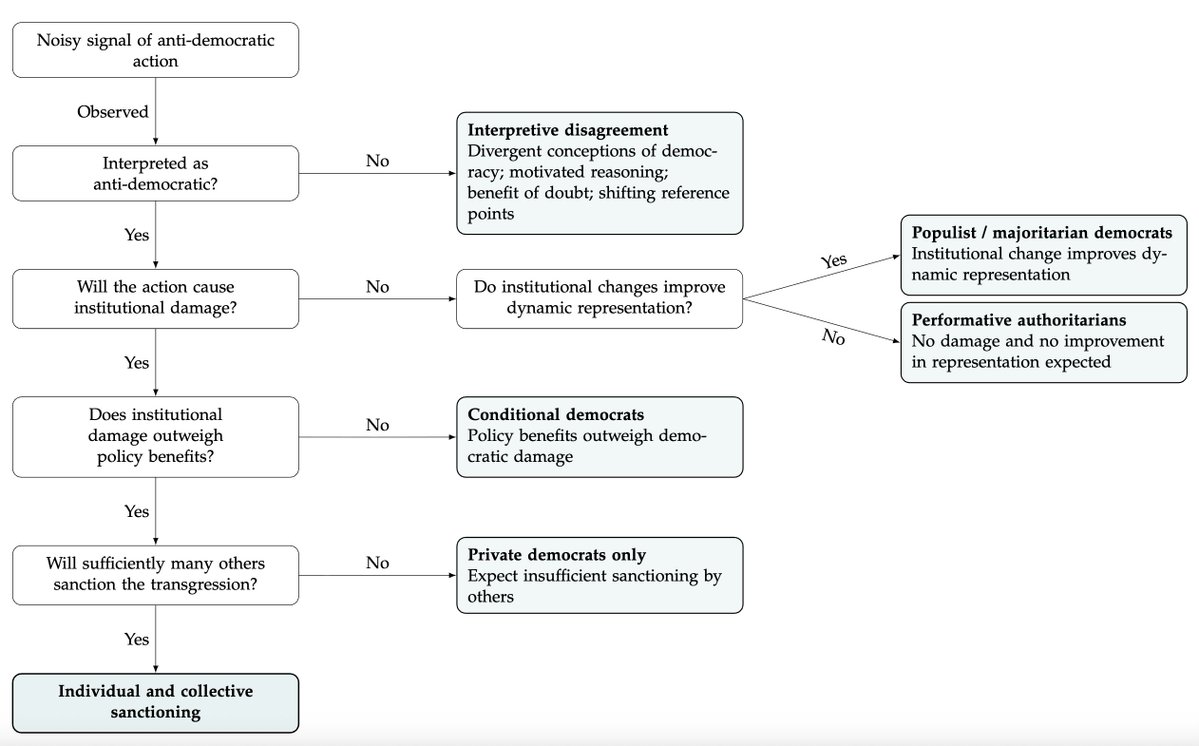

So public opinion explains outcomes "better"when the policy is consumer-facing, costs are salient, and attribution is easy (e.g. heating regulation -- hello, GEG, carbon pricing without revenue recycling, etc.). Interest group accounts, by contrast, are more helpful when

policymaking is technical, the costs for votetrs can be obscured, and implementation depends on cooperation from organised producers.

Where does geopolitics fit? It can reweight the mass and IG constraints:

▶️ energy price shocks can tighten the mass constraint

Where does geopolitics fit? It can reweight the mass and IG constraints:

▶️ energy price shocks can tighten the mass constraint

▶️ foreign competition can weaken producers (e.g. Chinese EV industry weakening the power of the German car industry)

Conclusion: The answer to the question depends on the stage of decarbonisation. Early(-ish) phases often look like interest-group politics (quiet,

Conclusion: The answer to the question depends on the stage of decarbonisation. Early(-ish) phases often look like interest-group politics (quiet,

producer-centred, design-heavy). Later phases increasingly look like mass politics (consumer-centred, visible incidence, compensation-heavy). At high stringency, external competition/geopolitics can gain greater importance, especially as the fiscal space (and other conditions,

e.g. polarisation, as in the US) required to relax the constraints domestically (e.g. via subsidising the green sector) narrows. The figure below tries to summarise this argument in a stylised way. As always, all of this is tentative. Let me know what you think.

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh