🧵What infection control failed to integrate

Outside formal IPC guidance, between 2013-2016 scientists were uncovering how everyday human activity generates infectious aerosols in indoor spaces, a finding with direct consequences for hospital transmission.

Outside formal IPC guidance, between 2013-2016 scientists were uncovering how everyday human activity generates infectious aerosols in indoor spaces, a finding with direct consequences for hospital transmission.

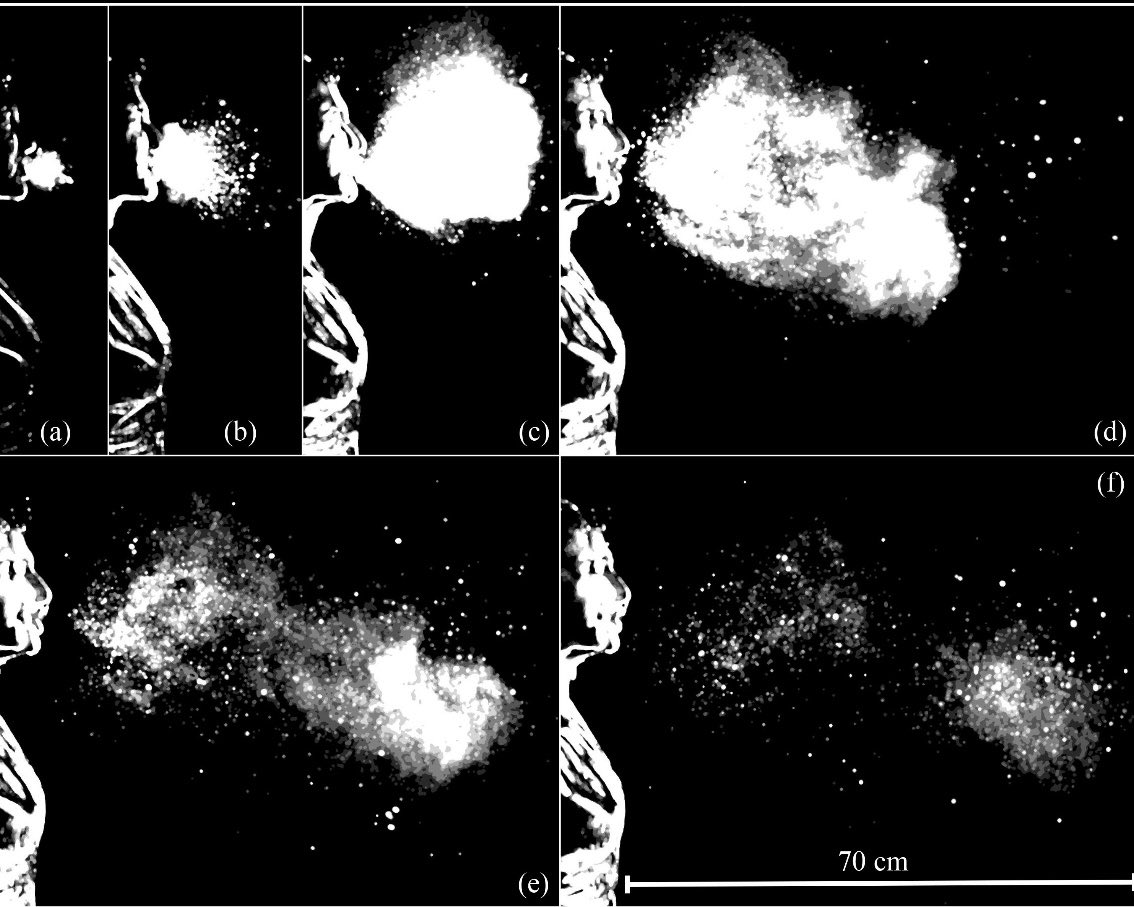

Using high-speed imaging, Lydia Bourouiba (MIT fluid dynamics) and colleagues showed that coughs, sneezes and speech produce turbulent gas clouds that generate fine aerosols capable of remaining suspended in shared air.

(JAMA 2014; NEJM 2016)

(JAMA 2014; NEJM 2016)

In parallel, Donald Milton (aerosol scientist & infectious disease researcher) demonstrated that infectious aerosols are produced during normal breathing NOT ONLY during coughing or symptomatic events.

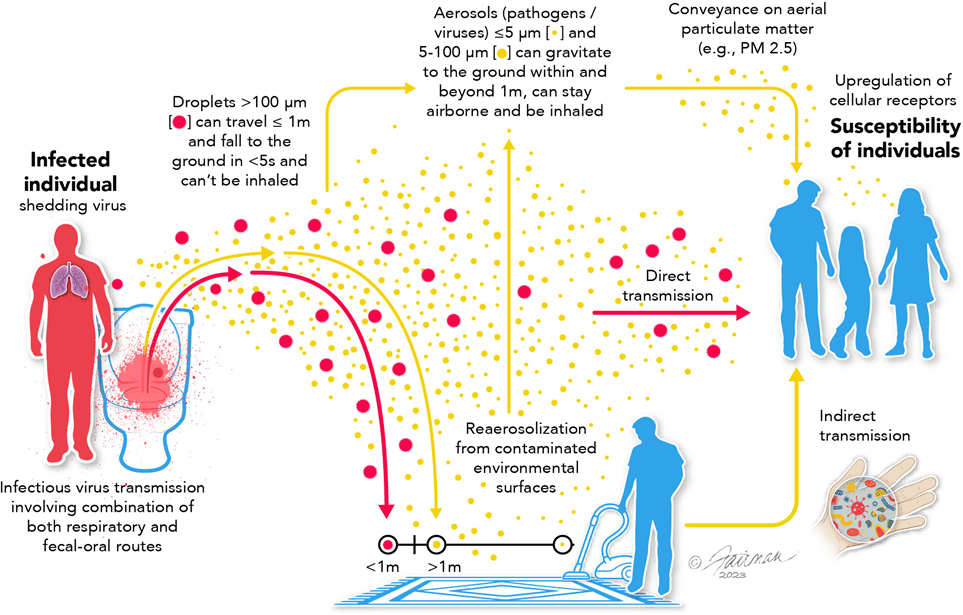

These findings overturned a core assumption of infection control: that exhaled particles either fall quickly to surfaces or dissipate at close range.

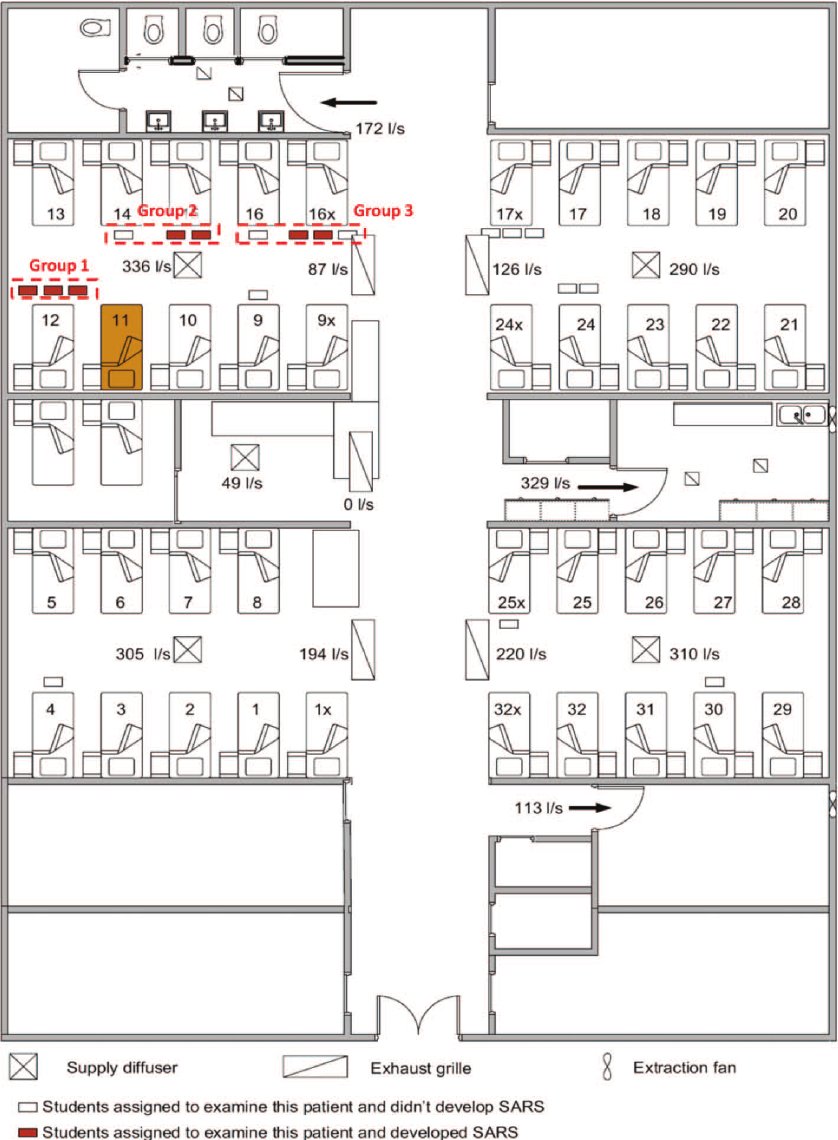

Instead, aerosols could persist and accumulate within indoor air.

Instead, aerosols could persist and accumulate within indoor air.

If aerosols were generated by normal breathing (Milton) and persisted in shared air (Bourouiba), then close-contact infection models were fundamentally flawed.

The droplet–aerosol distinction was no longer theoretical, it was operational.

The droplet–aerosol distinction was no longer theoretical, it was operational.

By 2016, aerosol transmission in hospitals was no longer speculative.

Yet Exercise Cygnus fixed UK pandemic planning to the wrong transmission model and IPC guidance then enforced it.

Yet Exercise Cygnus fixed UK pandemic planning to the wrong transmission model and IPC guidance then enforced it.

Sources:

• Bourouiba et al. J Fluid Mech (2014) “Violent expiratory events…”

doi.org/10.1017/jfm.20…

• Bourouiba. NEJM (2016) “A Sneeze”

nejm.org/doi/full/10.10…

• Milton et al. (2013) influenza virus in exhaled breath aerosols (PubMed)

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23505369/

• Bourouiba et al. J Fluid Mech (2014) “Violent expiratory events…”

doi.org/10.1017/jfm.20…

• Bourouiba. NEJM (2016) “A Sneeze”

nejm.org/doi/full/10.10…

• Milton et al. (2013) influenza virus in exhaled breath aerosols (PubMed)

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23505369/

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh