Building an evidence base on hospital-acquired COVID & patient safety failures, to secure proper investigation, accountability & learning - starting in Wales.

How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

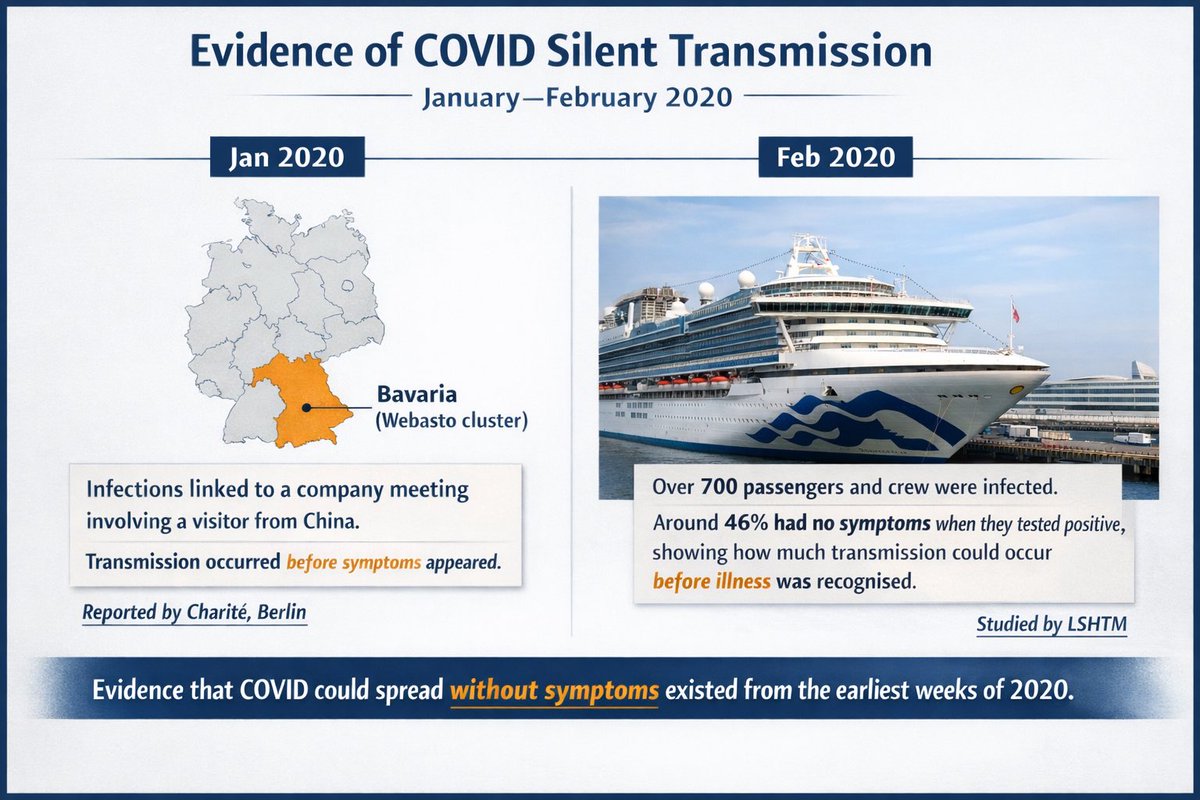

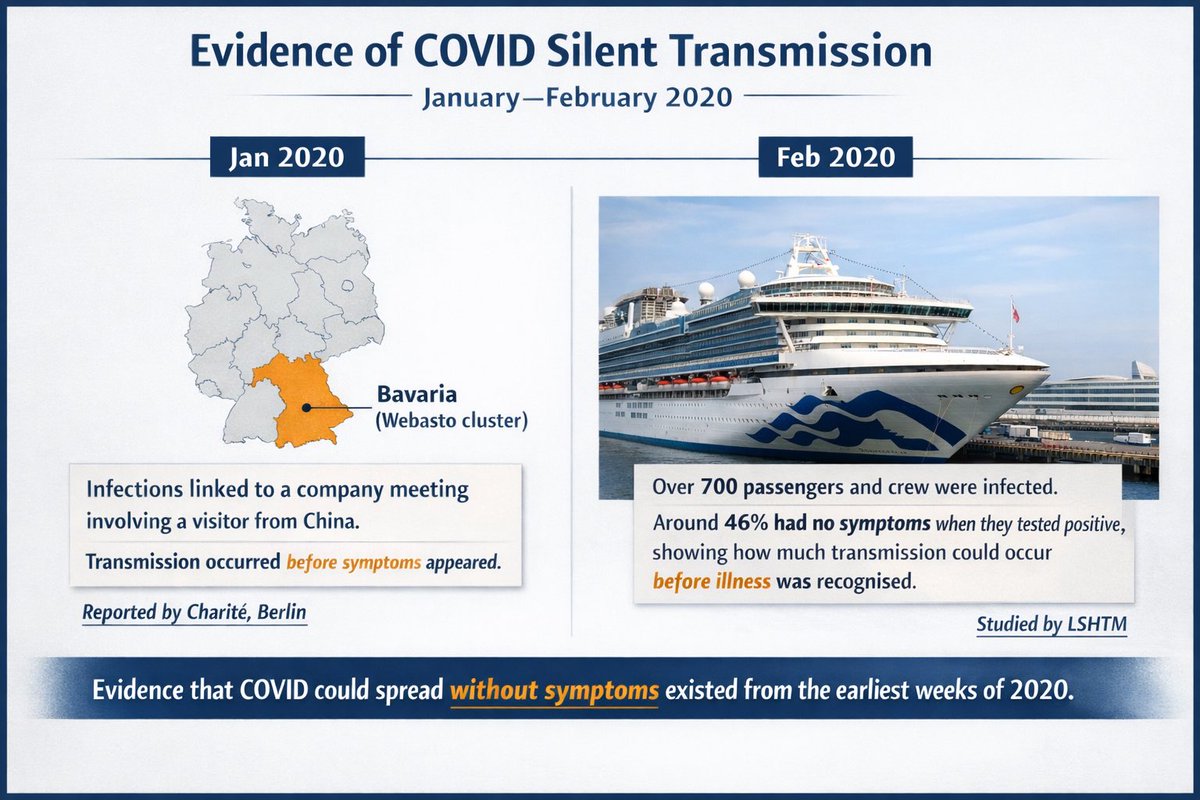

From the very start, scientists warned that people could spread SARS-CoV-2 before symptoms appeared.

From the very start, scientists warned that people could spread SARS-CoV-2 before symptoms appeared.

This wasn’t a blank slate.

This wasn’t a blank slate.

WHO Director-General,Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus @DrTedros stated that COVID was airborne. Following an off-mic exchange & note from Executive Director Dr Michael Ryan, he then corrected this to droplet transmission.

WHO Director-General,Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus @DrTedros stated that COVID was airborne. Following an off-mic exchange & note from Executive Director Dr Michael Ryan, he then corrected this to droplet transmission.

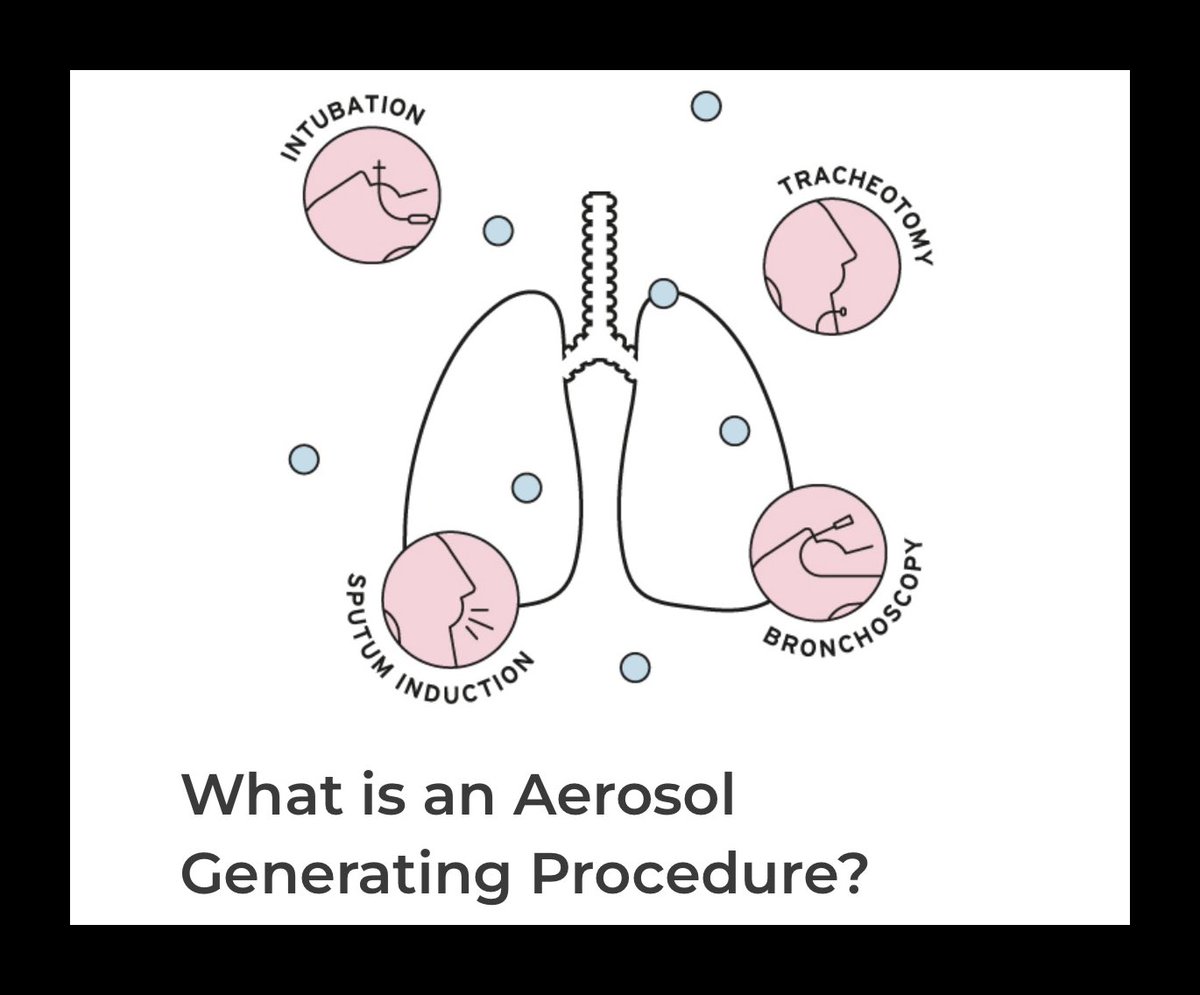

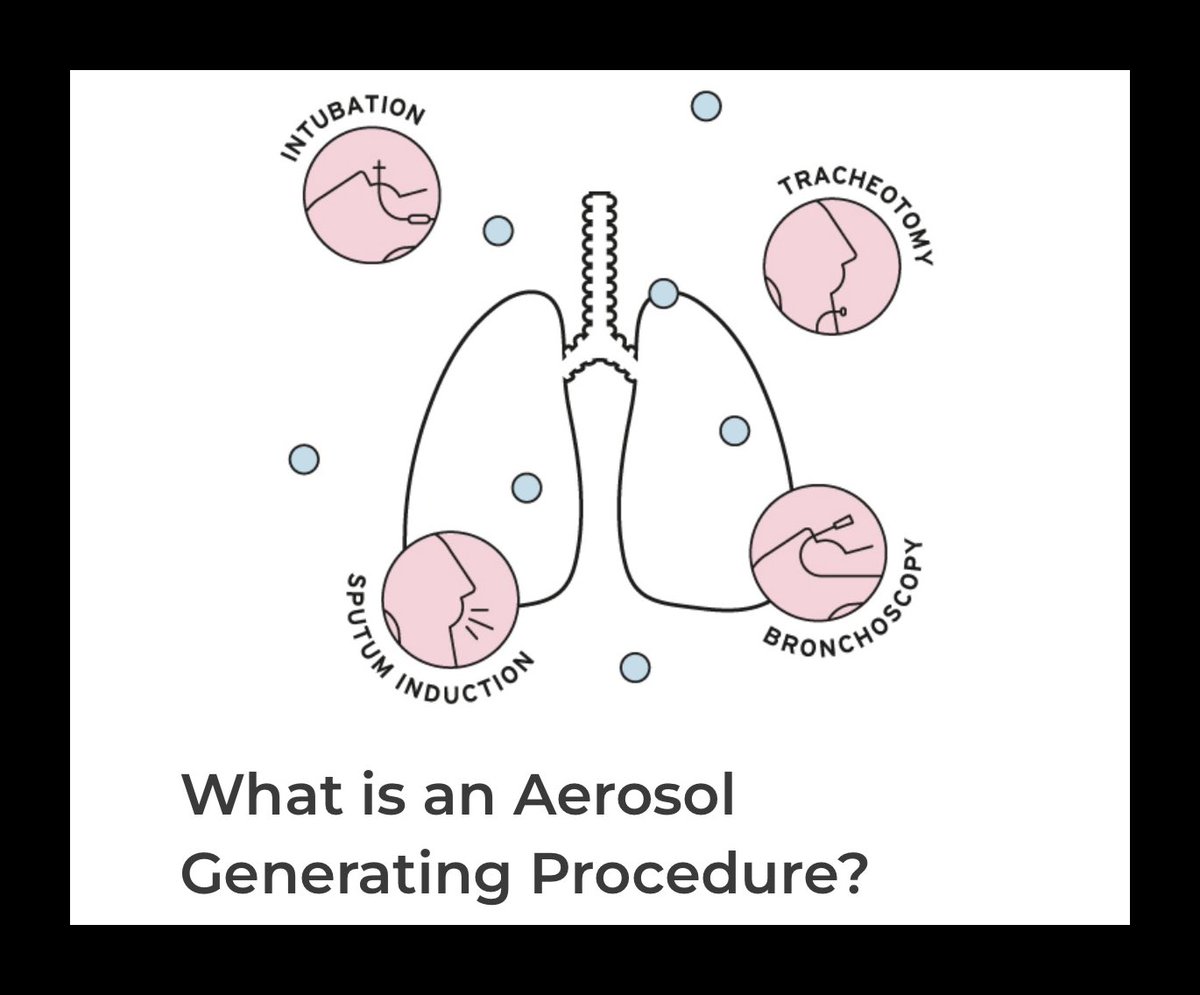

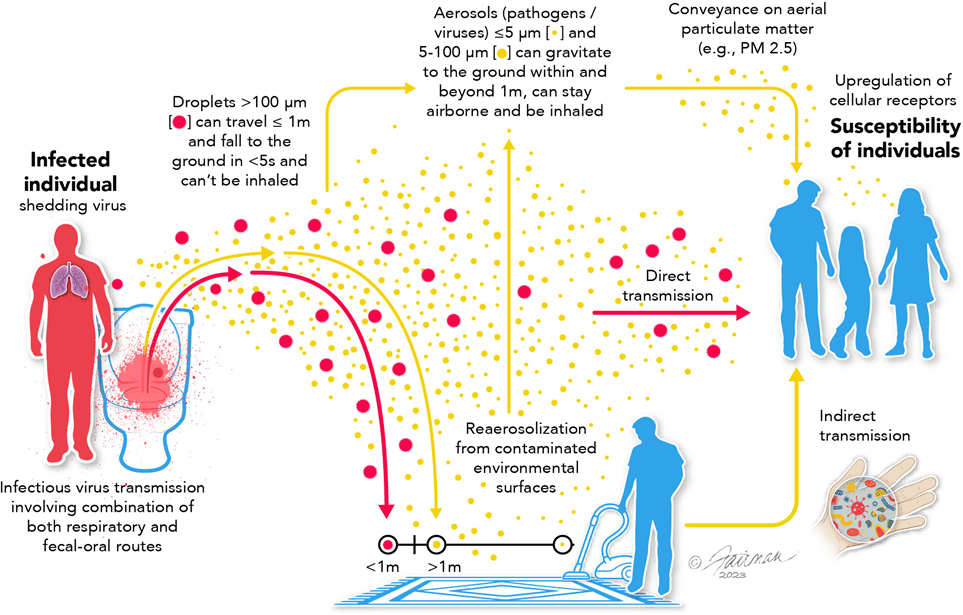

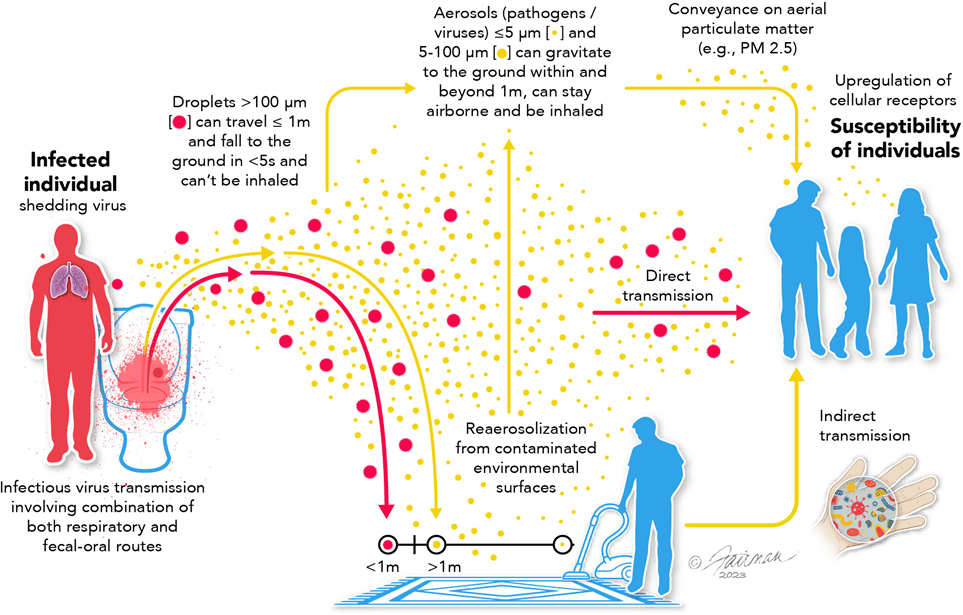

The rationale was procedural: disruptive airway interventions- intubation, suction, ventilation were assumed to generate aerosols in quantities capable of transmitting infection.

The rationale was procedural: disruptive airway interventions- intubation, suction, ventilation were assumed to generate aerosols in quantities capable of transmitting infection.

Across epidemiology, virology, and aerosol science, researchers were synthesising evidence from influenza, SARS-1, measles, and TB that challenged droplet-based infection models.

Across epidemiology, virology, and aerosol science, researchers were synthesising evidence from influenza, SARS-1, measles, and TB that challenged droplet-based infection models.

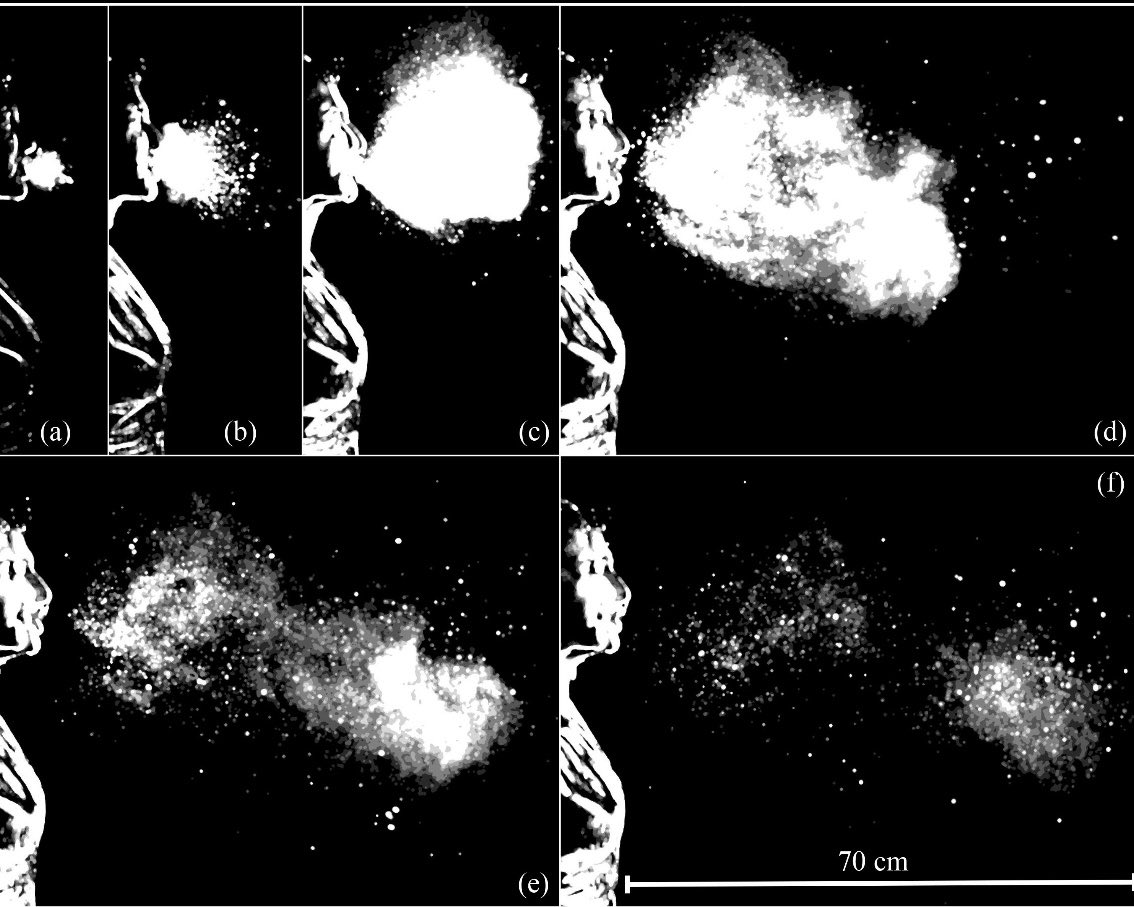

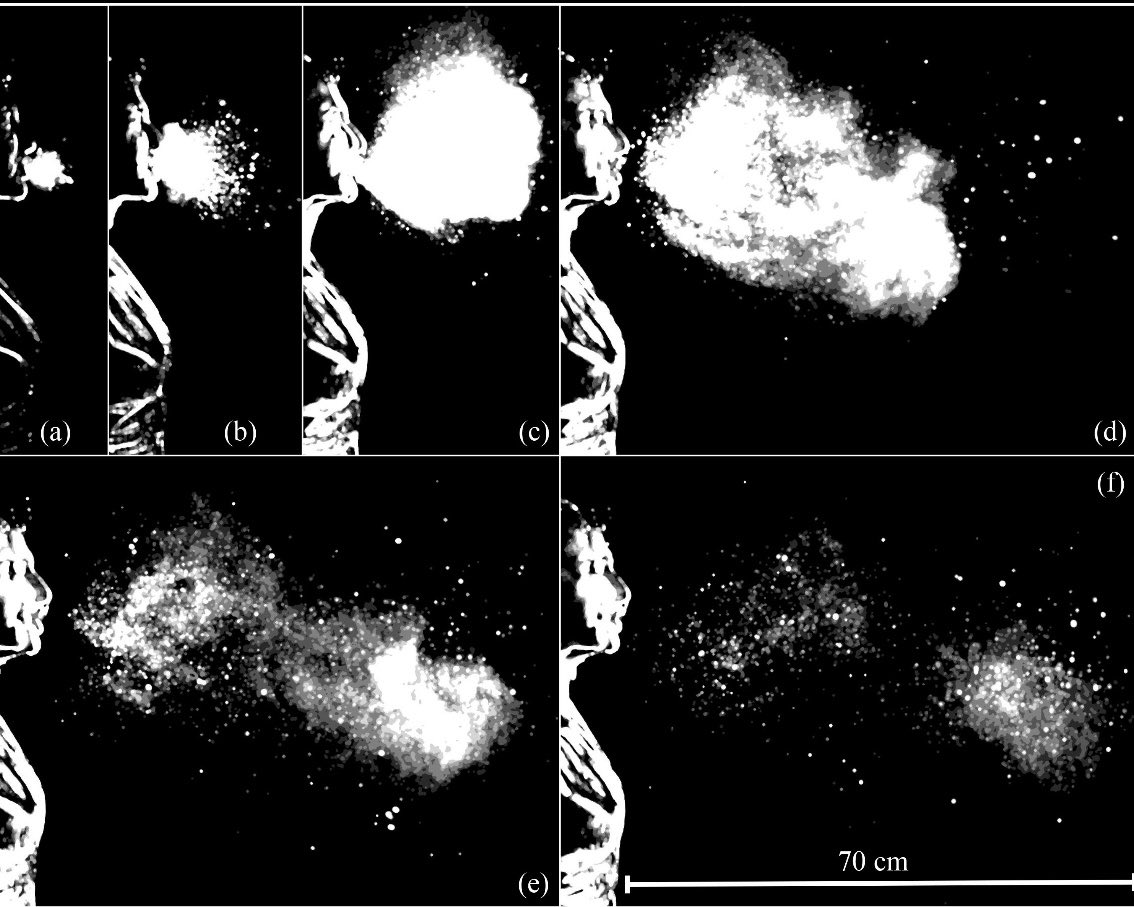

Using high-speed imaging, Lydia Bourouiba (MIT fluid dynamics) and colleagues showed that coughs, sneezes and speech produce turbulent gas clouds that generate fine aerosols capable of remaining suspended in shared air.

Using high-speed imaging, Lydia Bourouiba (MIT fluid dynamics) and colleagues showed that coughs, sneezes and speech produce turbulent gas clouds that generate fine aerosols capable of remaining suspended in shared air.

Aerosols are tiny particles released when people breathe, speak, cough, or shout.

Aerosols are tiny particles released when people breathe, speak, cough, or shout.