🧵 THREAD: The quiet revolution in aerosol transmission (2017–2019)

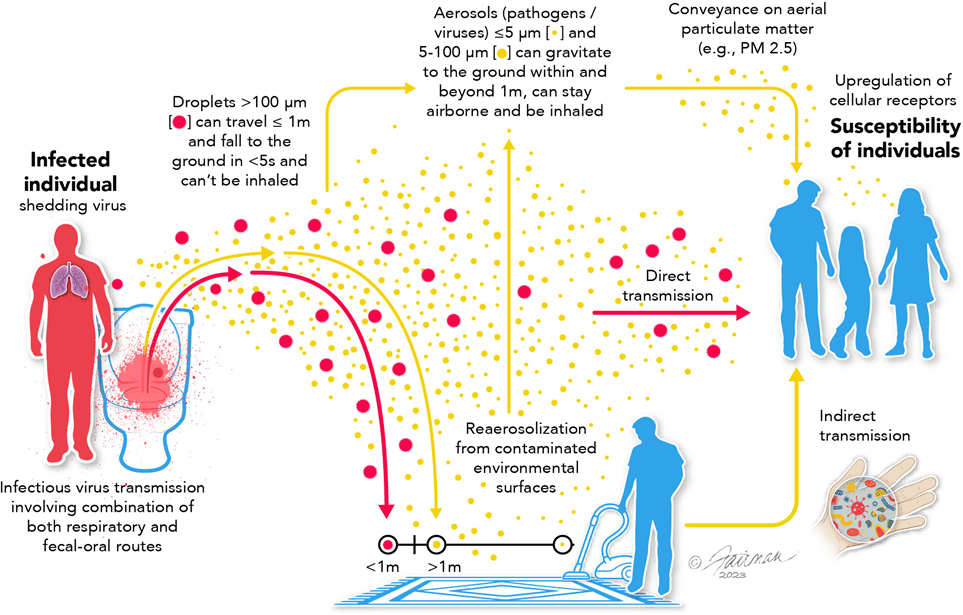

In the years just before COVID, scientists were increasingly clear that “droplet vs airborne” was a false binary and that real-world transmission didn’t fit it.

In the years just before COVID, scientists were increasingly clear that “droplet vs airborne” was a false binary and that real-world transmission didn’t fit it.

Across epidemiology, virology, and aerosol science, researchers were synthesising evidence from influenza, SARS-1, measles, and TB that challenged droplet-based infection models.

Scientists including Linsey Marr, Lidia Morawska, Julian Tang, Tellier, and Zeynep Tufekci were making this case publicly in papers, commentaries, and outbreak analyses.

I’ll cover their work in individual profile tweets.

I’ll cover their work in individual profile tweets.

Their argument wasn’t new physics. It was failure of fit.

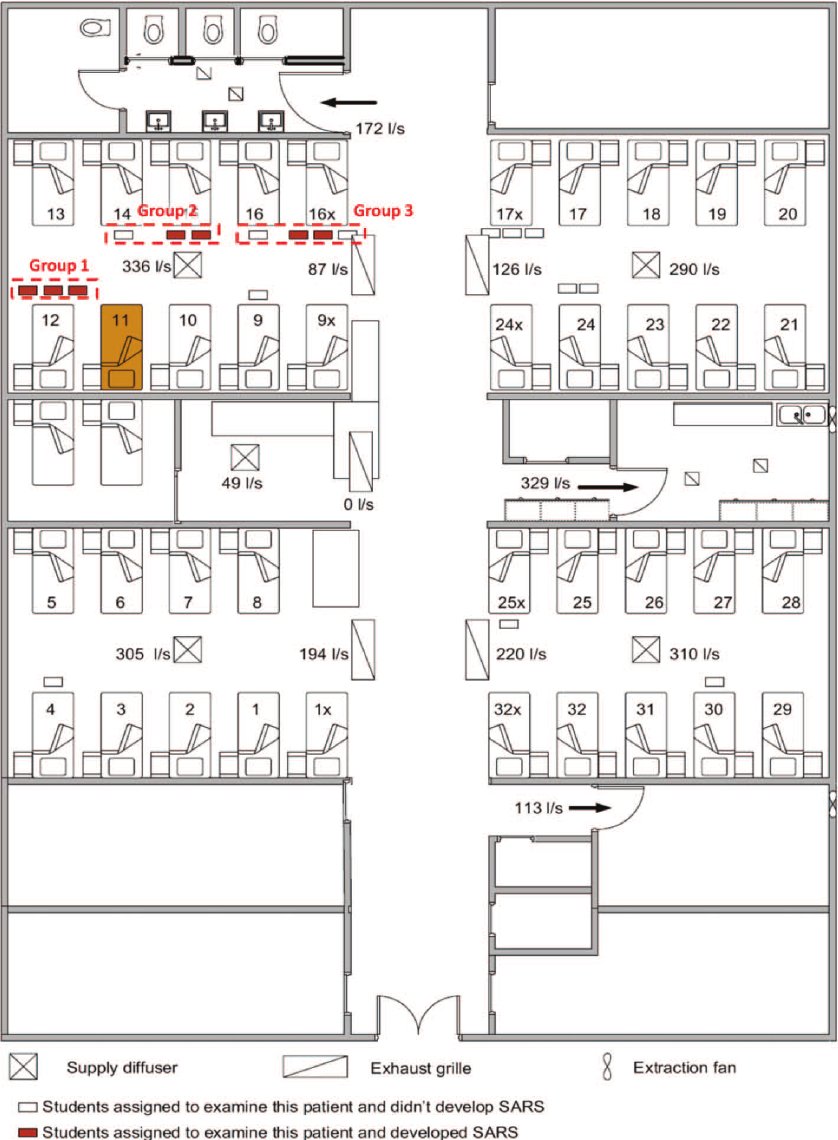

Droplet-based assumptions could not explain observed transmission patterns, especially in indoor settings.

Droplet-based assumptions could not explain observed transmission patterns, especially in indoor settings.

Outbreak investigations increasingly pointed to shared air, ventilation, and exposure time as dominant risk factors where distance, brief contact, or surface cleaning could not account for spread.

By 2019, many scientists were explicit: the droplet–airborne distinction was a false binary.

Transmission existed on a continuum shaped by indoor air with direct implications for hospitals.

Transmission existed on a continuum shaped by indoor air with direct implications for hospitals.

Sources include Morawska et al.; Marr et al.; Tellier et al.; Tang et al.; Tufekci commentaries (2017–2019).

Mini-profiles of each scientist to follow.

Mini-profiles of each scientist to follow.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh