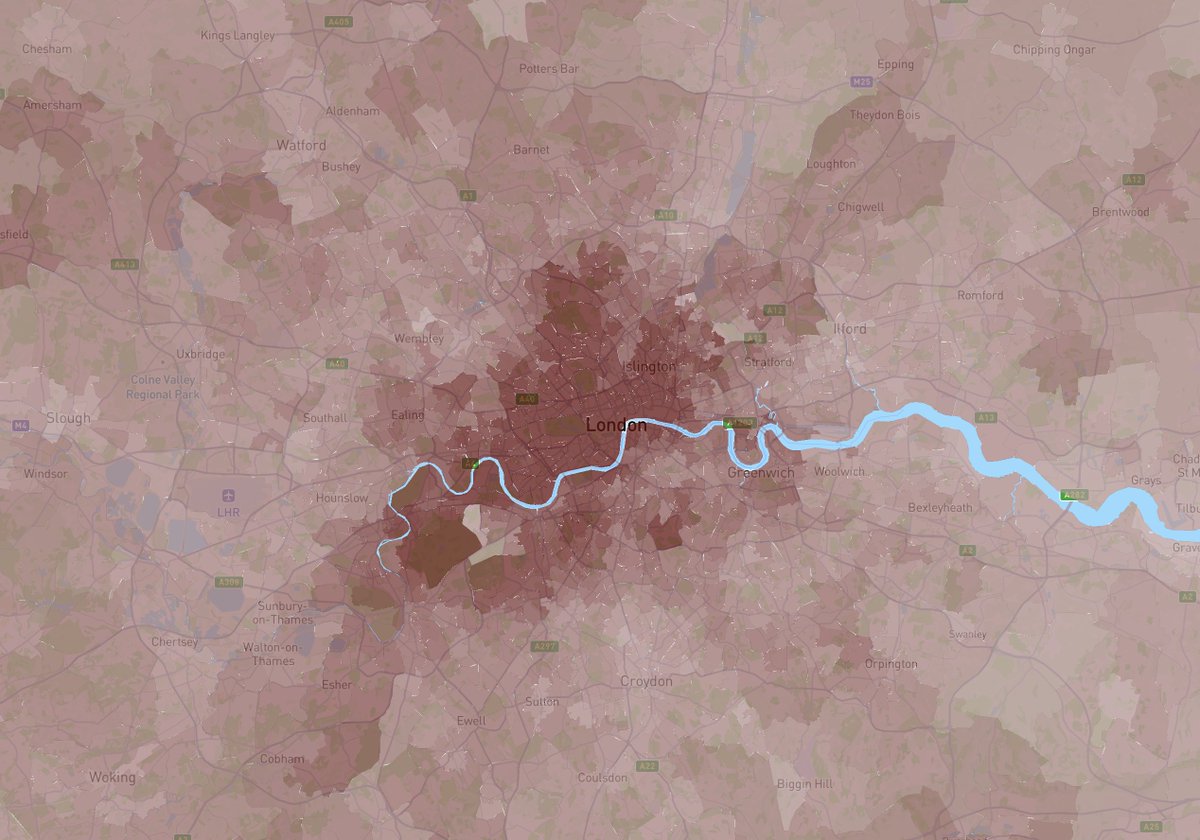

Thread of highlights from @Michael_J_Hil's excellent piece on Hackney Planning Dept's rationale for rejecting the hugely popular densification scheme 'Shoreditch Works', which would create space for 4,000 jobs on brownfield sites in central London.

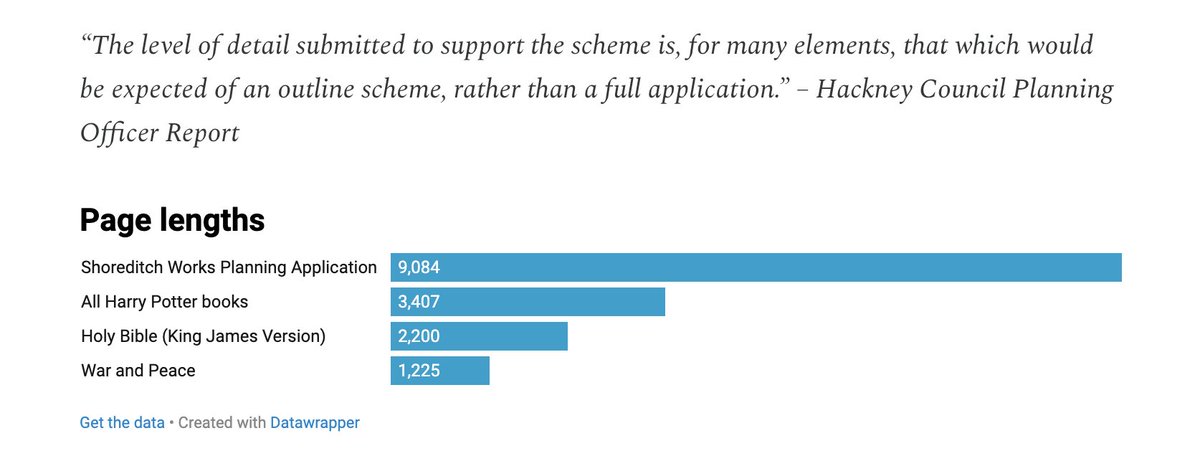

@Michael_J_Hil Although the planning application is some seven times longer than War and Peace and hundreds of times longer than early twentieth-century planning applications, the Dept considers it to be too short.

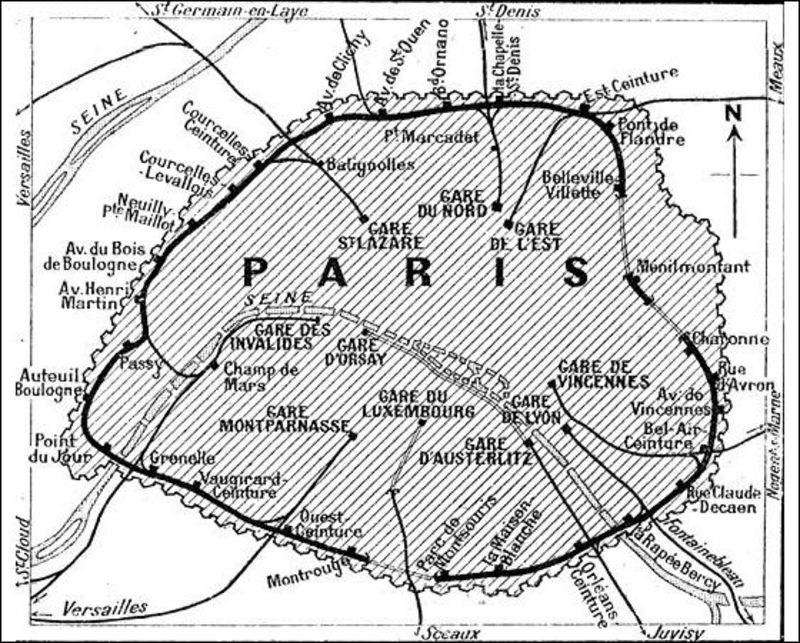

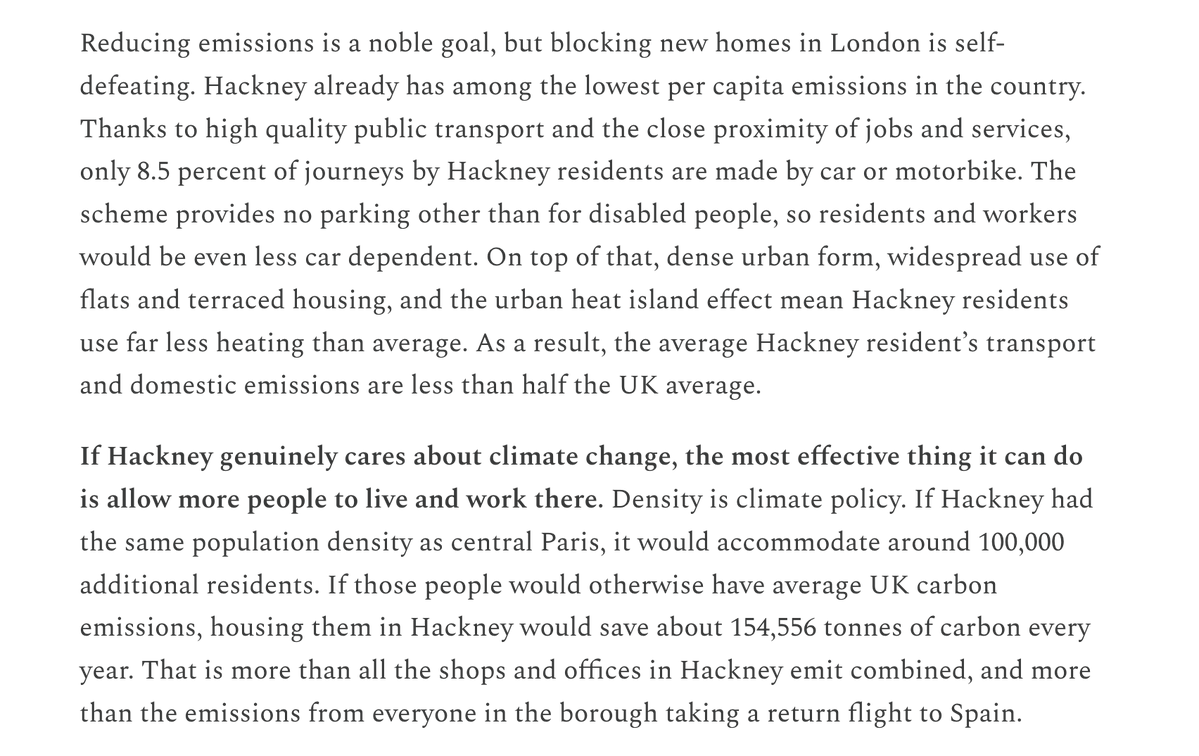

@Michael_J_Hil The developers have not provided enough evidence that the development will reduce greenhouse gas emissions, although there is overwhelming reason to believe it will.

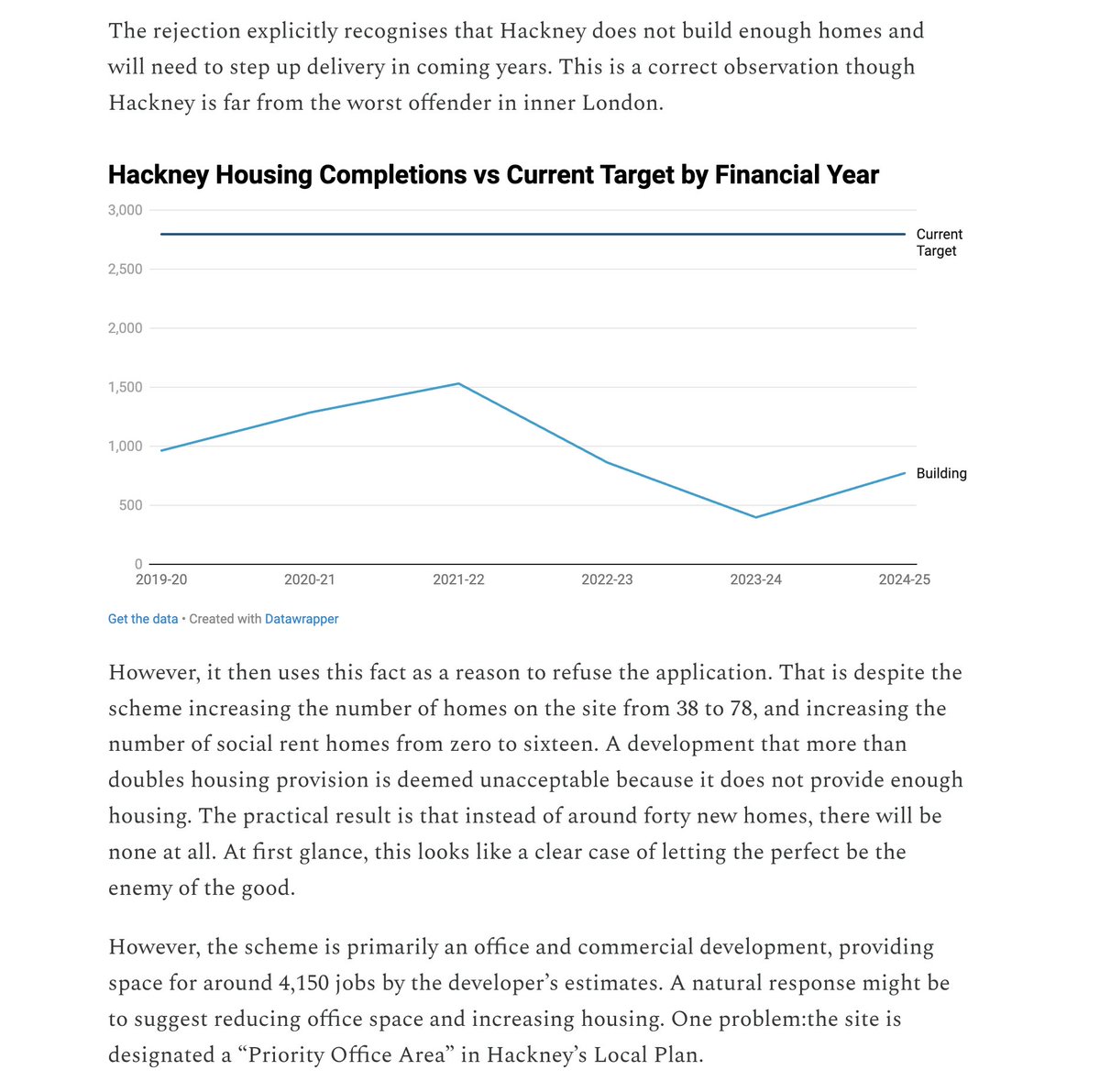

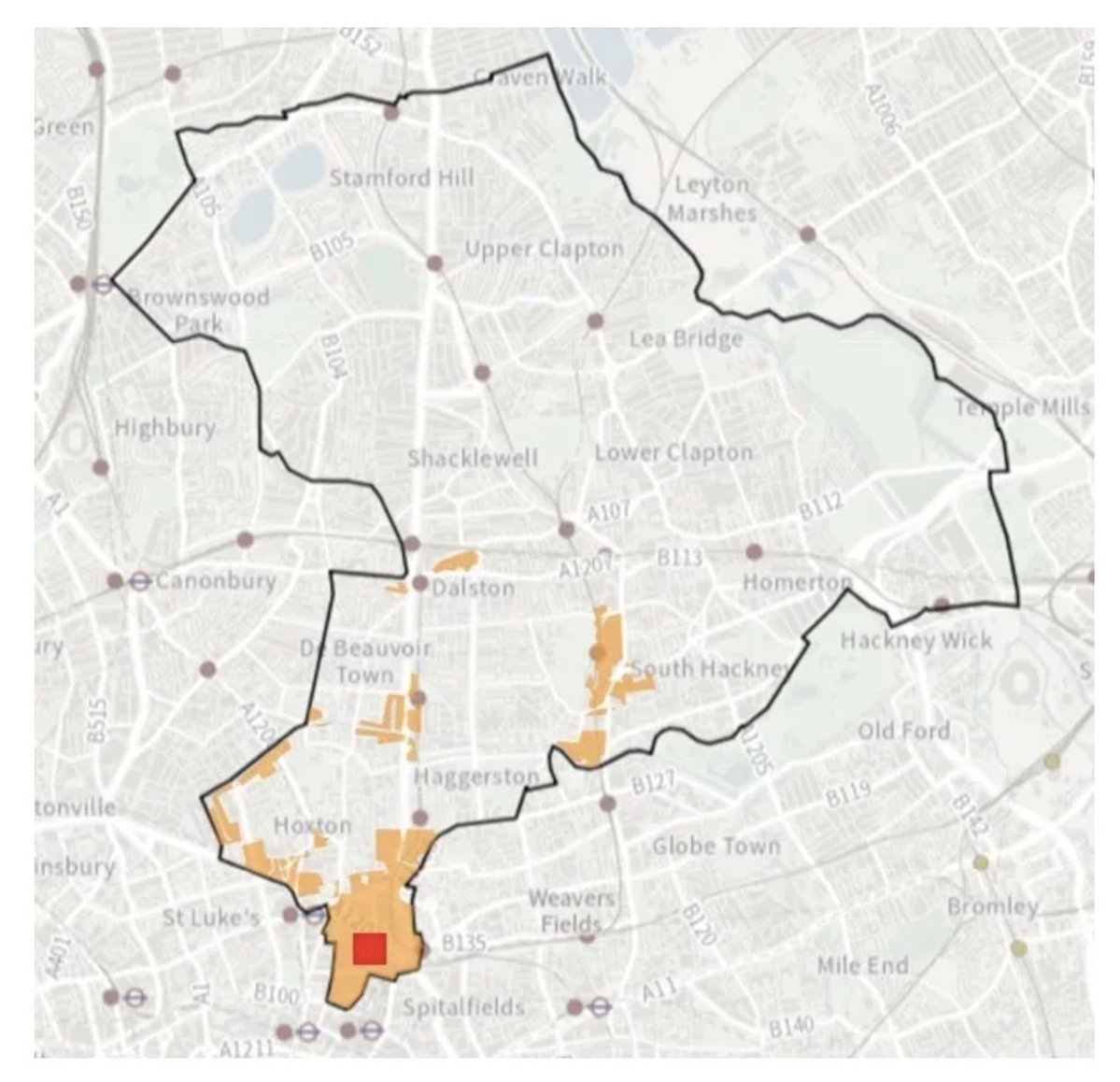

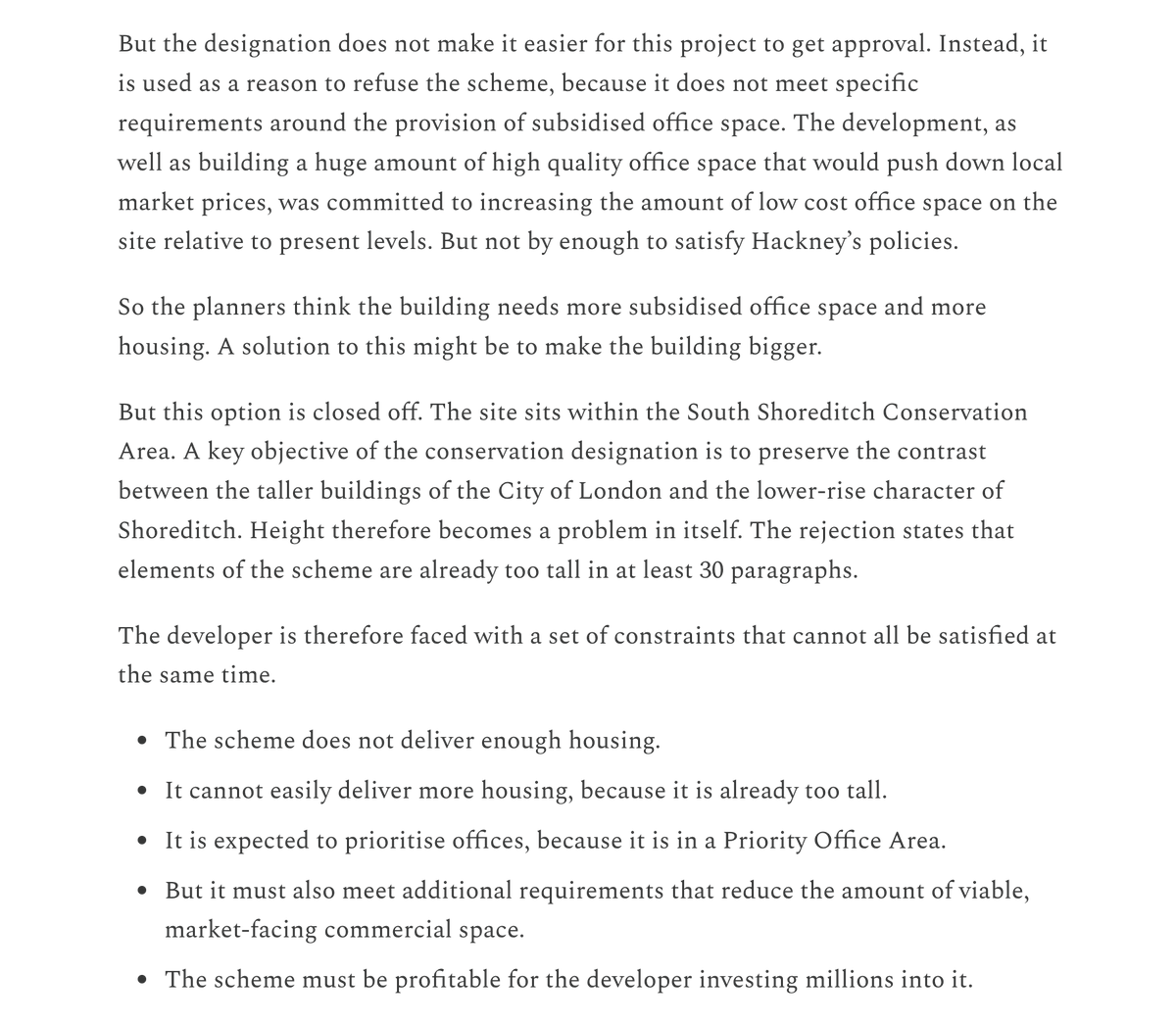

@Michael_J_Hil The development is too weighted towards offices, although Hackney itself has designated the site a 'Priority Office Area'.

@Michael_J_Hil The proposed buildings are too large, but also insufficient housing and affordable workspace is created.

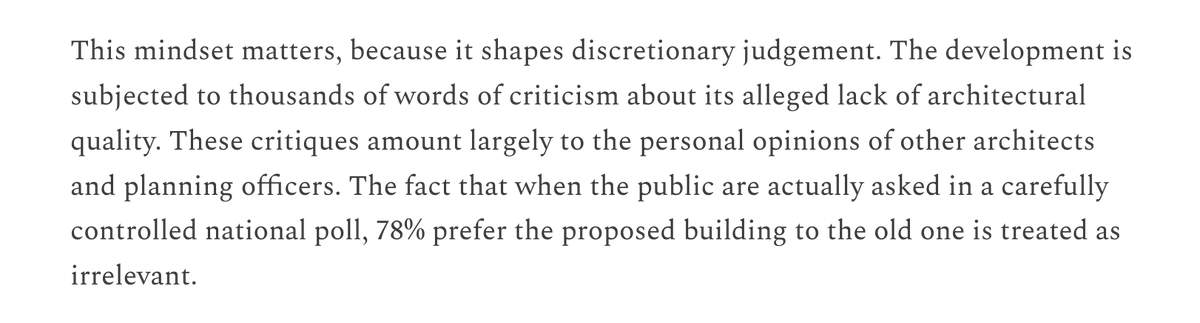

@Michael_J_Hil The Design Review Panel's disapproval is given much weight, while demonstrable public approval is not considered at all.

I know developers don't make the most convincing 'sob story' protagonists, but I do feel rather sorry for them, subject to this suite of bizarre, unreachable and mutually contradictory standards.

But you don't have to care about developers – you just need to care about growth, urbanism or climate, or about Hackney, or about London. I hope the councillors see reason in their meeting this evening.

Full details here: x.com/Michael_J_Hil/…

But you don't have to care about developers – you just need to care about growth, urbanism or climate, or about Hackney, or about London. I hope the councillors see reason in their meeting this evening.

Full details here: x.com/Michael_J_Hil/…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh