Editor @WorksInProgMag | Fellow @CPSThinkTank &

@createstreets | Interested in architecture & urbanism | Views my own

How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

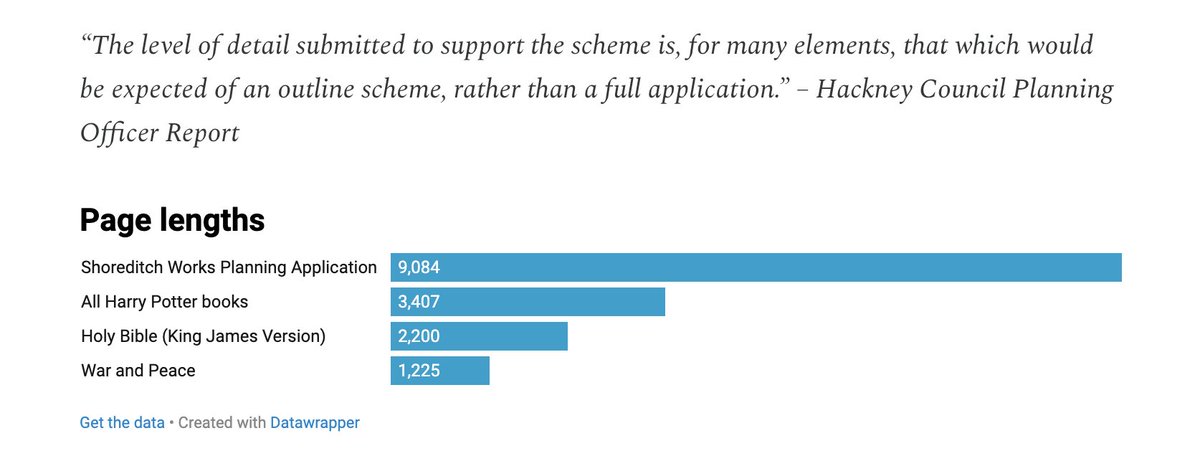

@Michael_J_Hil Although the planning application is some seven times longer than War and Peace and hundreds of times longer than early twentieth-century planning applications, the Dept considers it to be too short.

@Michael_J_Hil Although the planning application is some seven times longer than War and Peace and hundreds of times longer than early twentieth-century planning applications, the Dept considers it to be too short.

The key context is that England’s housing shortage is heavily concentrated in certain areas, as shown by Anna Powell-Smith's map of floorspace values below. We should generally focus housebuilding in these areas, because:

The key context is that England’s housing shortage is heavily concentrated in certain areas, as shown by Anna Powell-Smith's map of floorspace values below. We should generally focus housebuilding in these areas, because:

The headline reason for the collapse of housebuilding is the establishment of a quango called the Building Safety Regulator, whose approval has been required since April 2024 (after a transitional period starting in 2023) for all tall buildings.

The headline reason for the collapse of housebuilding is the establishment of a quango called the Building Safety Regulator, whose approval has been required since April 2024 (after a transitional period starting in 2023) for all tall buildings.

First, let's remember when this happened. The decline starts around 1920. Population continues to fall until about 1990, although gentrification had already started in the 1970s and 80s. Since then, the population has risen steadily.

First, let's remember when this happened. The decline starts around 1920. Population continues to fall until about 1990, although gentrification had already started in the 1970s and 80s. Since then, the population has risen steadily.

Tokugawa cities obviously did not have trains, trams, buses or cars. More surprisingly, they made little use of wheeled transport, relying on pack animals, canals and porters. This meant they only needed narrow and crooked roads.

Tokugawa cities obviously did not have trains, trams, buses or cars. More surprisingly, they made little use of wheeled transport, relying on pack animals, canals and porters. This meant they only needed narrow and crooked roads.

This was an epoch-defining achievement. But when they reached existing cities, the Victorians faced a key constraint: they did not have the technology to bore tunnels deep under cities, and it was fantastically contentious and expensive to plough through them.

This was an epoch-defining achievement. But when they reached existing cities, the Victorians faced a key constraint: they did not have the technology to bore tunnels deep under cities, and it was fantastically contentious and expensive to plough through them.

The reason was that the garden squares raised the value of nearby houses, which were sold by the same developers. They raised it by so much that it outweighed the opportunity cost of not building houses on the squares themselves.

The reason was that the garden squares raised the value of nearby houses, which were sold by the same developers. They raised it by so much that it outweighed the opportunity cost of not building houses on the squares themselves.

Most of the expansion of London took place on 'Great Estates', land owned by various church bodies, charities, guilds and aristocratic families. These are some of the survivors today, but originally there were far more.

Most of the expansion of London took place on 'Great Estates', land owned by various church bodies, charities, guilds and aristocratic families. These are some of the survivors today, but originally there were far more.

Proposals include a new concourse under the platforms running between new entrances on both sides, the pedestrianisation of Cab Road and Mepham Street, the opening up of viaduct arches for shops and restaurants, and the peninsularisation of the currently appalling 'Imax Plaza'.

Proposals include a new concourse under the platforms running between new entrances on both sides, the pedestrianisation of Cab Road and Mepham Street, the opening up of viaduct arches for shops and restaurants, and the peninsularisation of the currently appalling 'Imax Plaza'.

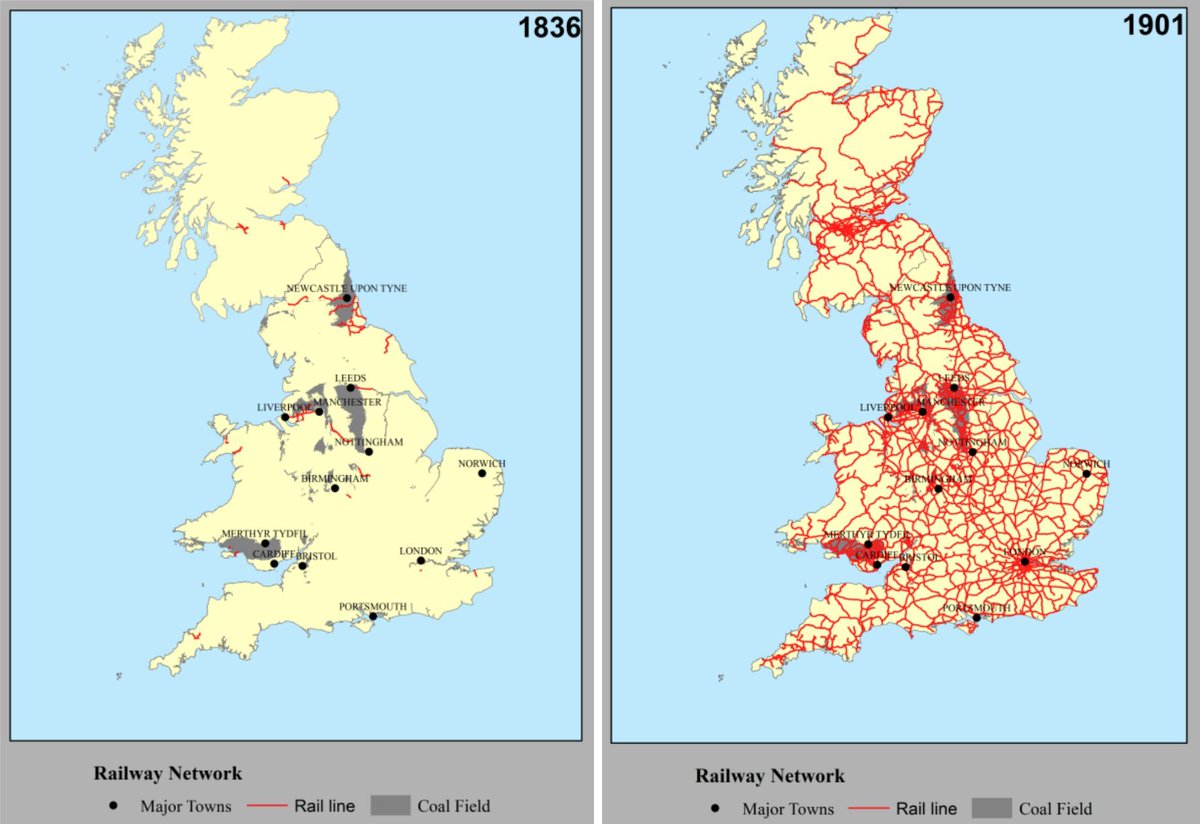

Between 1830 and 1900, railway companies built some 20,000 miles of intercity railways, giving Britain the best railway system in the world. (For comparison, HS2 to Birmingham is 143 miles.)

Between 1830 and 1900, railway companies built some 20,000 miles of intercity railways, giving Britain the best railway system in the world. (For comparison, HS2 to Birmingham is 143 miles.)

@UKDayOne @KaneEmerson To succeed, new towns need to tie into existing cities with shortages of housing and laboratory space, as I argued in this recent BD piece. Doing so helps the new towns flourish and alleviates the shortages in existing centres.

@UKDayOne @KaneEmerson To succeed, new towns need to tie into existing cities with shortages of housing and laboratory space, as I argued in this recent BD piece. Doing so helps the new towns flourish and alleviates the shortages in existing centres.

The Romans founded planned new towns, like York, Chester and Gloucester. The Saxons founded them at places like Oxford and Wareham. Many planned towns were founded in the Middle Ages, of which Salisbury is famous.

The Romans founded planned new towns, like York, Chester and Gloucester. The Saxons founded them at places like Oxford and Wareham. Many planned towns were founded in the Middle Ages, of which Salisbury is famous.

Like many myths, this is partly true. In premodern societies, making ornament generally did take a great deal of craftsmanship.

Like many myths, this is partly true. In premodern societies, making ornament generally did take a great deal of craftsmanship.

Now, §1 sets out only the ‘simplified method’. §2 allows builders to do ‘dynamic thermal modelling’, potentially allowing larger windows. But this is more complex and costly. There is a risk that large windows have effectively been banned in new homes for people on lower incomes.

Now, §1 sets out only the ‘simplified method’. §2 allows builders to do ‘dynamic thermal modelling’, potentially allowing larger windows. But this is more complex and costly. There is a risk that large windows have effectively been banned in new homes for people on lower incomes.

Such framing is extremely common in older urbanism, creating a kind of artistic mutual dependence between the great public buildings and the fabric of the city around them. Here, Amiens.

Such framing is extremely common in older urbanism, creating a kind of artistic mutual dependence between the great public buildings and the fabric of the city around them. Here, Amiens.

The architect of the 1959-60 work, Stephen Dykes Bower, bequeathed everything he had to help fund the completion of the church, which was led by Warwick Pethers.

The architect of the 1959-60 work, Stephen Dykes Bower, bequeathed everything he had to help fund the completion of the church, which was led by Warwick Pethers.

Of the street, in his characteristic striking style, LC wrote: 'There is neither the pride which results from order, nor the spirit of initiative which is engendered by wide spaces ... only pitying compassion born of the shock of encountering the faces of our fellows.'

Of the street, in his characteristic striking style, LC wrote: 'There is neither the pride which results from order, nor the spirit of initiative which is engendered by wide spaces ... only pitying compassion born of the shock of encountering the faces of our fellows.'

Externally however the change was rather a disaster, as may be seen by comparing the one facade that retains them (R) to the incoherent ones without. Suggested moral: windows are hugely important for enlivening and articulating facades, over and above their utilitarian value.

Externally however the change was rather a disaster, as may be seen by comparing the one facade that retains them (R) to the incoherent ones without. Suggested moral: windows are hugely important for enlivening and articulating facades, over and above their utilitarian value.

Only a qualified version of the regulations applied in pre-1780 areas, but in arondissements XIII-XX the new rules had astonishingly rapid effects. Of course the mood shifted rapidly, and in 1974 Paris returned to a version of its ancient regulations.

Only a qualified version of the regulations applied in pre-1780 areas, but in arondissements XIII-XX the new rules had astonishingly rapid effects. Of course the mood shifted rapidly, and in 1974 Paris returned to a version of its ancient regulations.