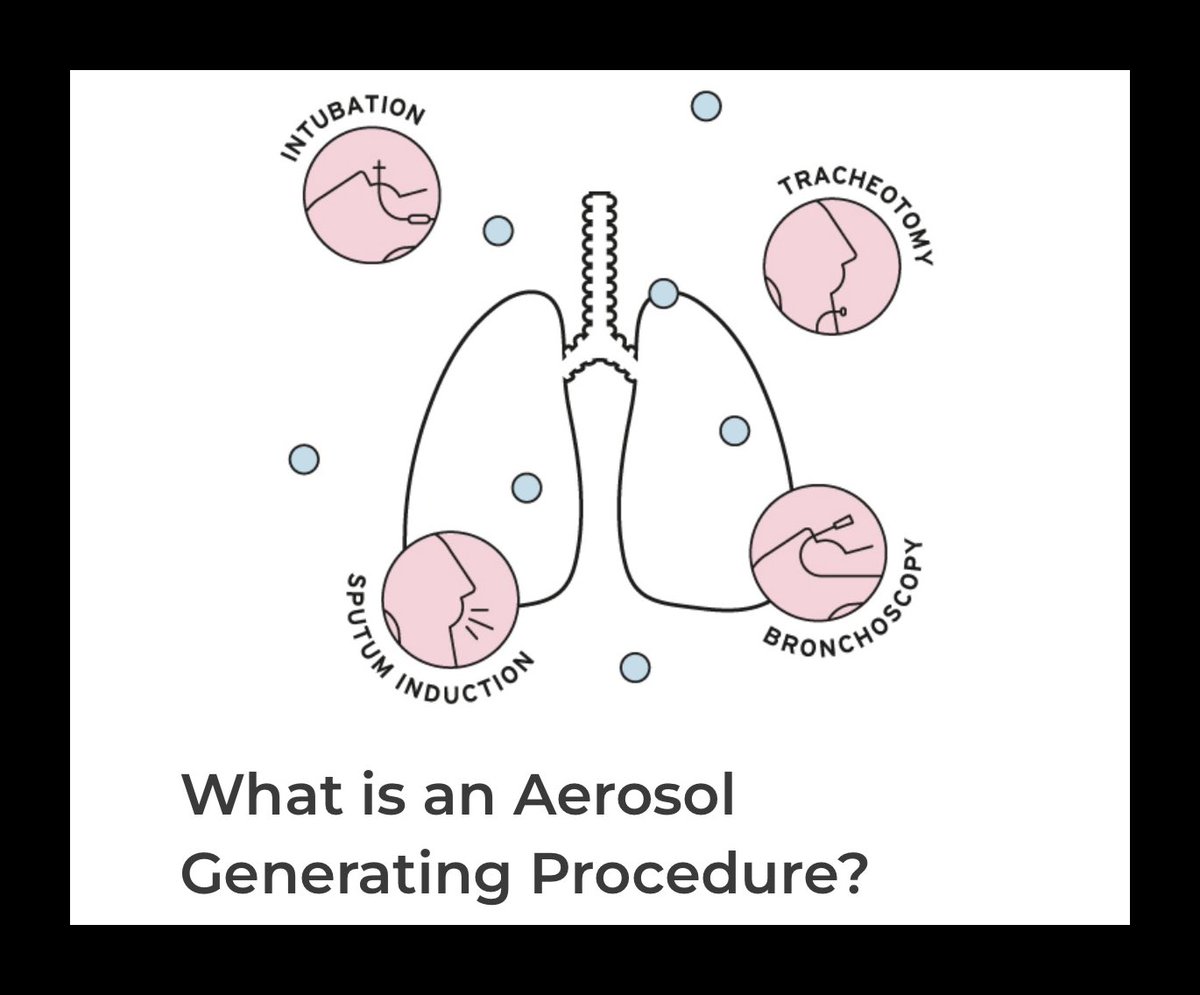

Aerosol Generating Procedures (AGPs) are clinical interventions historically believed to be the only situations producing infectious aerosols triggering higher respiratory protection.

They became the cornerstone of respiratory IPC risk stratification.

They became the cornerstone of respiratory IPC risk stratification.

The rationale was procedural: disruptive airway interventions- intubation, suction, ventilation were assumed to generate aerosols in quantities capable of transmitting infection.

Routine respiratory activity was not considered comparable risk.

Routine respiratory activity was not considered comparable risk.

Protection doctrine followed that assumption.

Respirator protection (FFP3/N95) was restricted to AGPs.

Routine care was managed under droplet precautions.

Respirator protection (FFP3/N95) was restricted to AGPs.

Routine care was managed under droplet precautions.

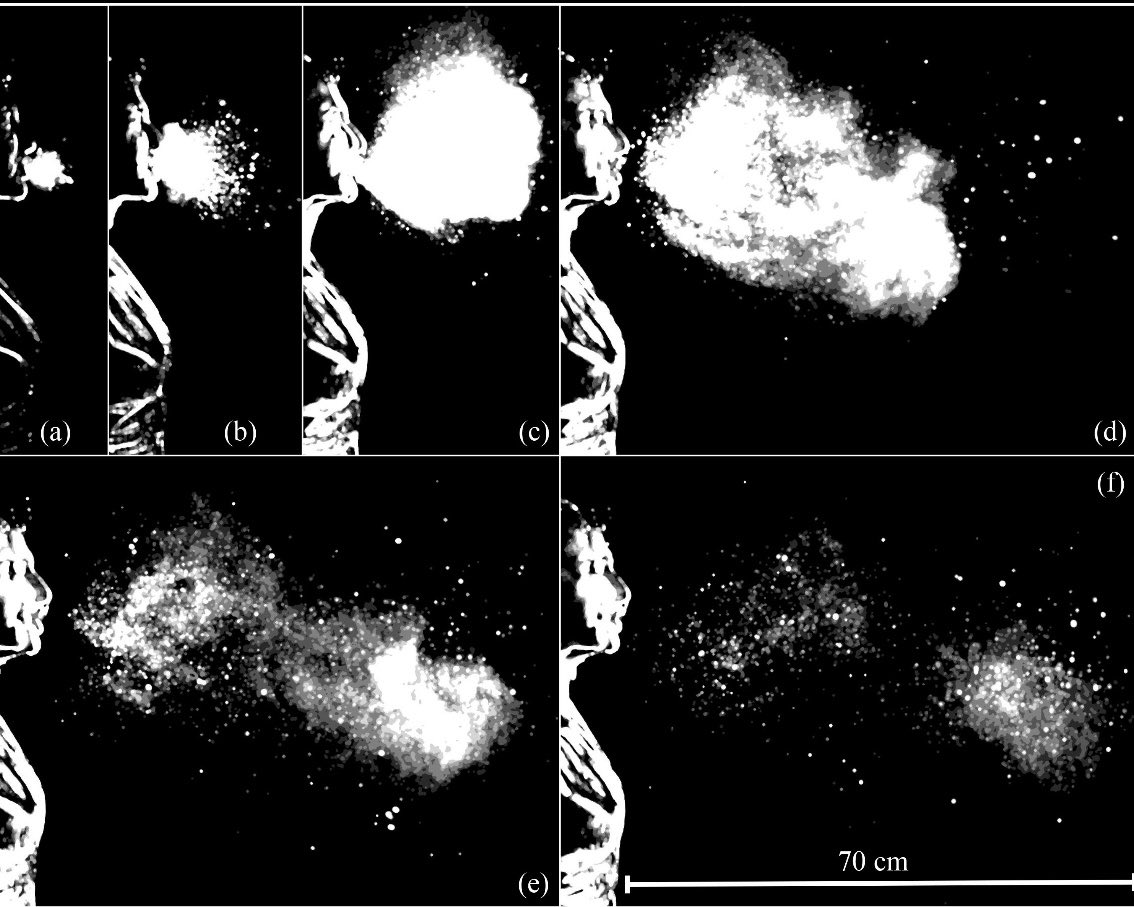

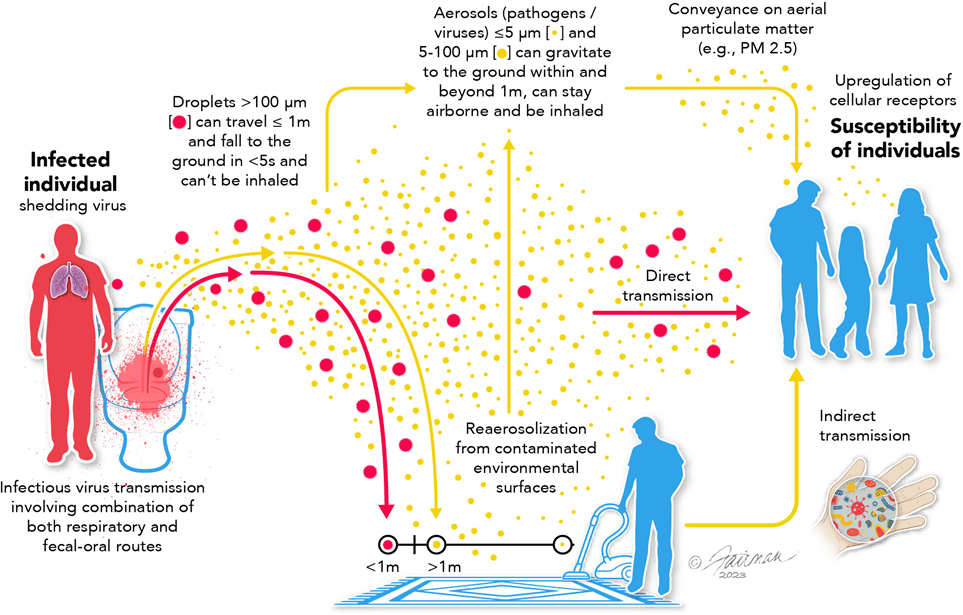

But aerosols aren’t procedure-dependent.

They are produced whenever an infected person exhales - breathing, talking, coughing.

A virus does not become infectious because of a procedure.

They are produced whenever an infected person exhales - breathing, talking, coughing.

A virus does not become infectious because of a procedure.

By the 2010s, aerosol science had already demonstrated this: infectious aerosols are generated through normal respiratory activity and persist in shared indoor air.

(See previous threads.)

(See previous threads.)

Despite this, IPC frameworks continued to treat aerosol risk as primarily AGP-associated.

Respirator access remained procedure-triggered.

Respirator access remained procedure-triggered.

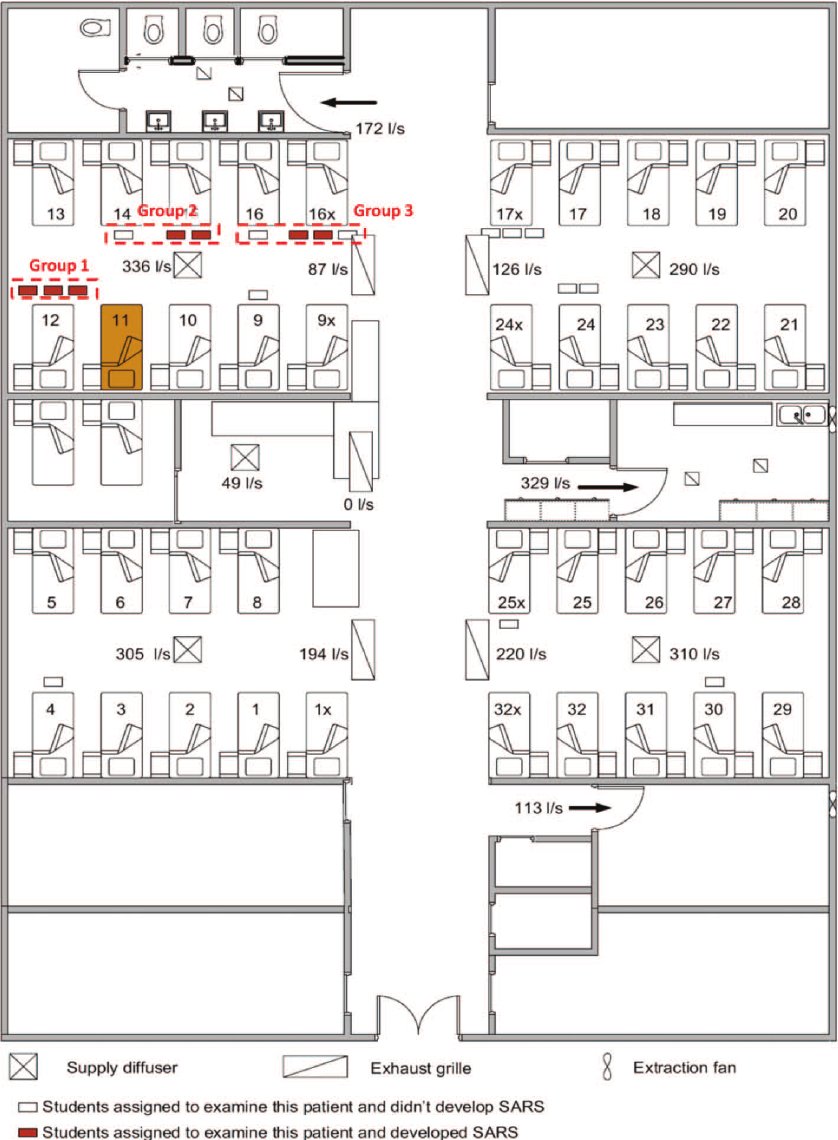

If aerosols are continuously generated, exposure risk exists throughout patient care NOT just during procedures.

Restricting respirators to AGPs misclassifies where risk occurs.

Restricting respirators to AGPs misclassifies where risk occurs.

COVID IPC guidance inherited this doctrine.

Respirator protection remained tied to procedures even as a novel respiratory virus spread through shared air.

Next 🧵: how AGP doctrine shaped healthcare worker protection during COVID.

Respirator protection remained tied to procedures even as a novel respiratory virus spread through shared air.

Next 🧵: how AGP doctrine shaped healthcare worker protection during COVID.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh