How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

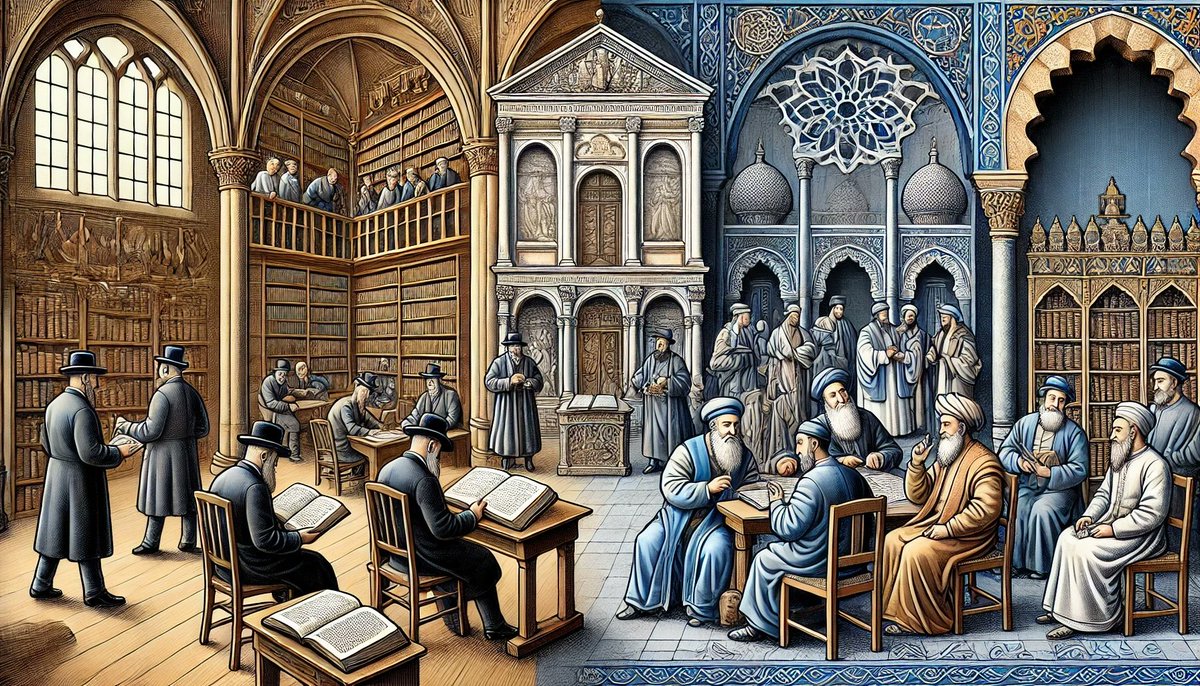

🧵 (2/3) From Yaḇne to Usha, Shefarʿam, Sepphoris, and finally Tiberias, each city carried the Sanhedrin’s embers forward. Around 200 CE, Ribbi Yehuḏa haNasi (c. 135–217 CE), son of Rabban Shimʿon ben Gamliel II, compiled and edited the Mishna, codifying oral deliberation into a framework capable of outlasting empire. When Roman Judea collapsed in revolt after revolt — the First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE), the Kitos War (115–117 CE), and the Bar Kokhḇa Revolt (132–136 CE) — entire regions were emptied, yet law persisted. Cassius Dio records 580,000 dead, 50 fortresses, and 985 villages destroyed. Even if exaggerated, archaeology confirms large-scale depopulation. And the Judean, and Samaritan population has been demoralized, and susptiable to capture mentally. By the mid-third century, as noted earlier, Ribbi Yose bar Ḥanina articulated the lesson of survival: after three failed rebellions, restraint itself became almost doctrine (yet of course, through the centuries political leaders did rise), preservation through patience. Revolt had exhausted revolt.

🧵 (2/3) From Yaḇne to Usha, Shefarʿam, Sepphoris, and finally Tiberias, each city carried the Sanhedrin’s embers forward. Around 200 CE, Ribbi Yehuḏa haNasi (c. 135–217 CE), son of Rabban Shimʿon ben Gamliel II, compiled and edited the Mishna, codifying oral deliberation into a framework capable of outlasting empire. When Roman Judea collapsed in revolt after revolt — the First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE), the Kitos War (115–117 CE), and the Bar Kokhḇa Revolt (132–136 CE) — entire regions were emptied, yet law persisted. Cassius Dio records 580,000 dead, 50 fortresses, and 985 villages destroyed. Even if exaggerated, archaeology confirms large-scale depopulation. And the Judean, and Samaritan population has been demoralized, and susptiable to capture mentally. By the mid-third century, as noted earlier, Ribbi Yose bar Ḥanina articulated the lesson of survival: after three failed rebellions, restraint itself became almost doctrine (yet of course, through the centuries political leaders did rise), preservation through patience. Revolt had exhausted revolt.

📚 Jewish Encyclopedia 1912 + Wissenschaft des Judentums

📚 Jewish Encyclopedia 1912 + Wissenschaft des Judentums

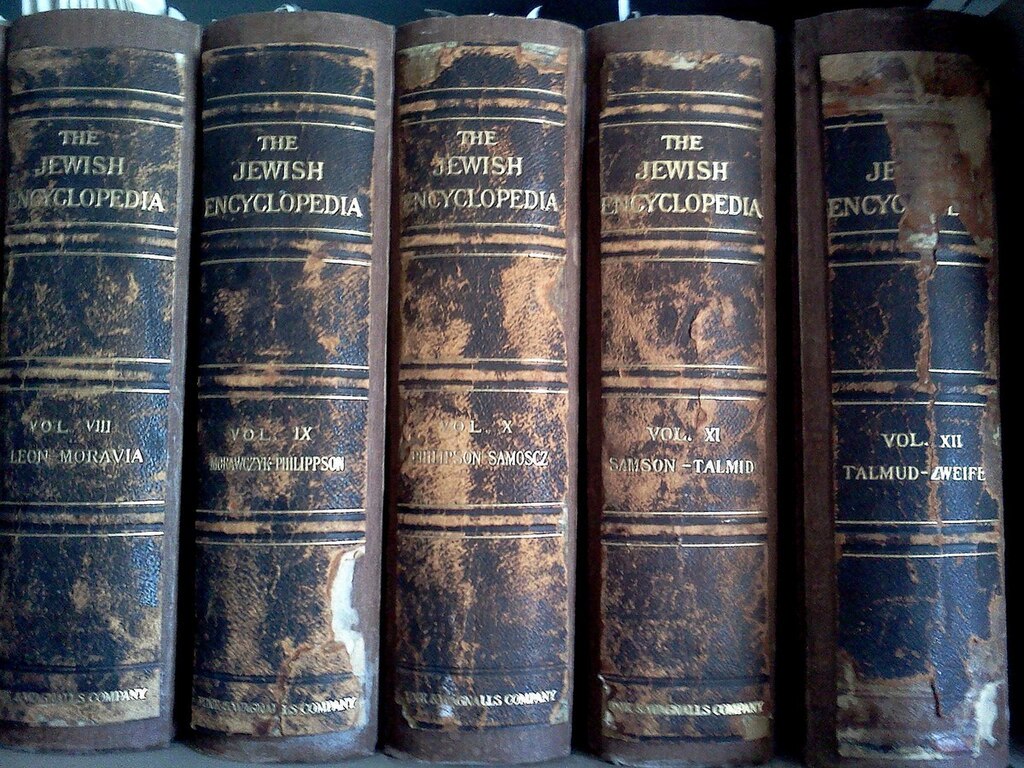

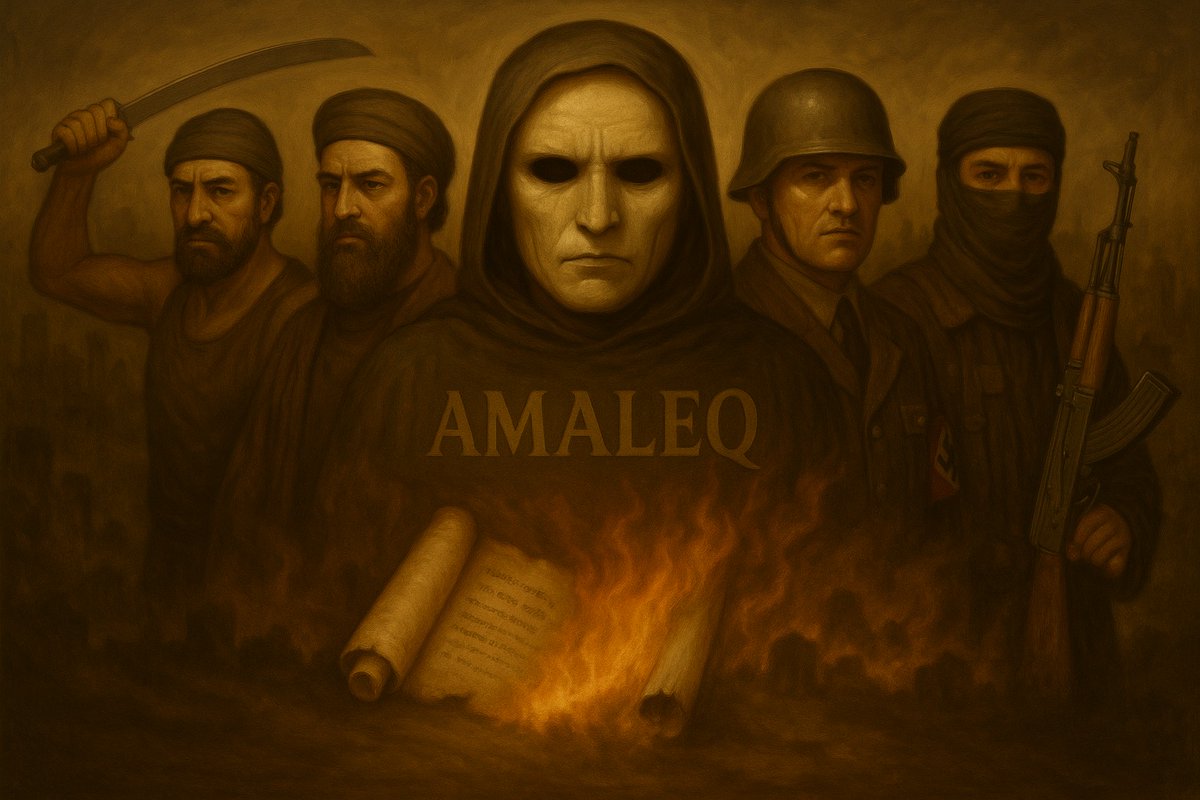

When Jews call Hamas "Amaleq," we are invoking zekher to name cruelty. To resist its return, whether in ancient garb or modern uniforms. You want to talk scripture? Let’s talk. But if you weaponize our texts while ignoring ʿAqṣā Deluge theology, Shahada propaganda, and genocidal hadiths chanted in real time, then you’re not after truth. You’re after absolution.

When Jews call Hamas "Amaleq," we are invoking zekher to name cruelty. To resist its return, whether in ancient garb or modern uniforms. You want to talk scripture? Let’s talk. But if you weaponize our texts while ignoring ʿAqṣā Deluge theology, Shahada propaganda, and genocidal hadiths chanted in real time, then you’re not after truth. You’re after absolution.

People are stuck in the world of “X is a language and so distinct.” But these are post-Enlightenment categories. Modern linguistics carved boundaries that living speakers never recognized.

People are stuck in the world of “X is a language and so distinct.” But these are post-Enlightenment categories. Modern linguistics carved boundaries that living speakers never recognized.

🏛️ Iraq Before Shlaim, Co-existence

🏛️ Iraq Before Shlaim, Co-existence

worldjewishcongress.org/en/legacy-of-j…

worldjewishcongress.org/en/legacy-of-j…

Encountering Reality: Knowledge as a Miṣva

Encountering Reality: Knowledge as a Miṣva

✍️🏽The Meghilla and the Debate Over Writing

✍️🏽The Meghilla and the Debate Over Writing

🕍 Jesus' Identity Embedded in Jewish Tradition

🕍 Jesus' Identity Embedded in Jewish Tradition

🐉 Peterson’s Perspective: The Reality Within Myth

🐉 Peterson’s Perspective: The Reality Within Myth

📜 Historical and Religious Significance

📜 Historical and Religious Significance

🌐 Internet and Social Popularity

🌐 Internet and Social Popularity

📜 Age of Riḇqa in the Tora

📜 Age of Riḇqa in the Tora

📚 Wissenschaft des Judentums Movement

📚 Wissenschaft des Judentums Movement

❓ Why so Reclusive?

❓ Why so Reclusive?

🌍 Pan-Arabism: Origins and Aspirations

🌍 Pan-Arabism: Origins and Aspirations