Researcher @CREIResearch, working on international macroeconomics.

2 subscribers

How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

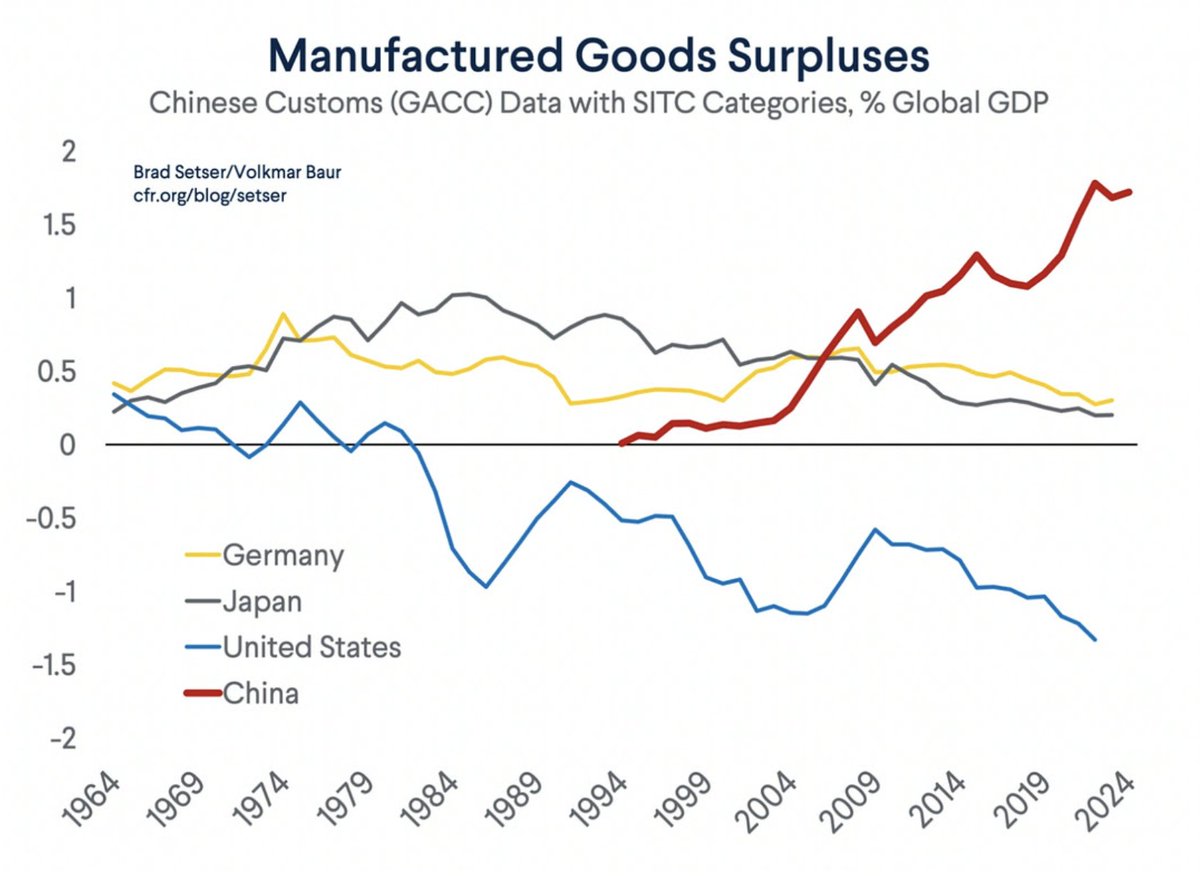

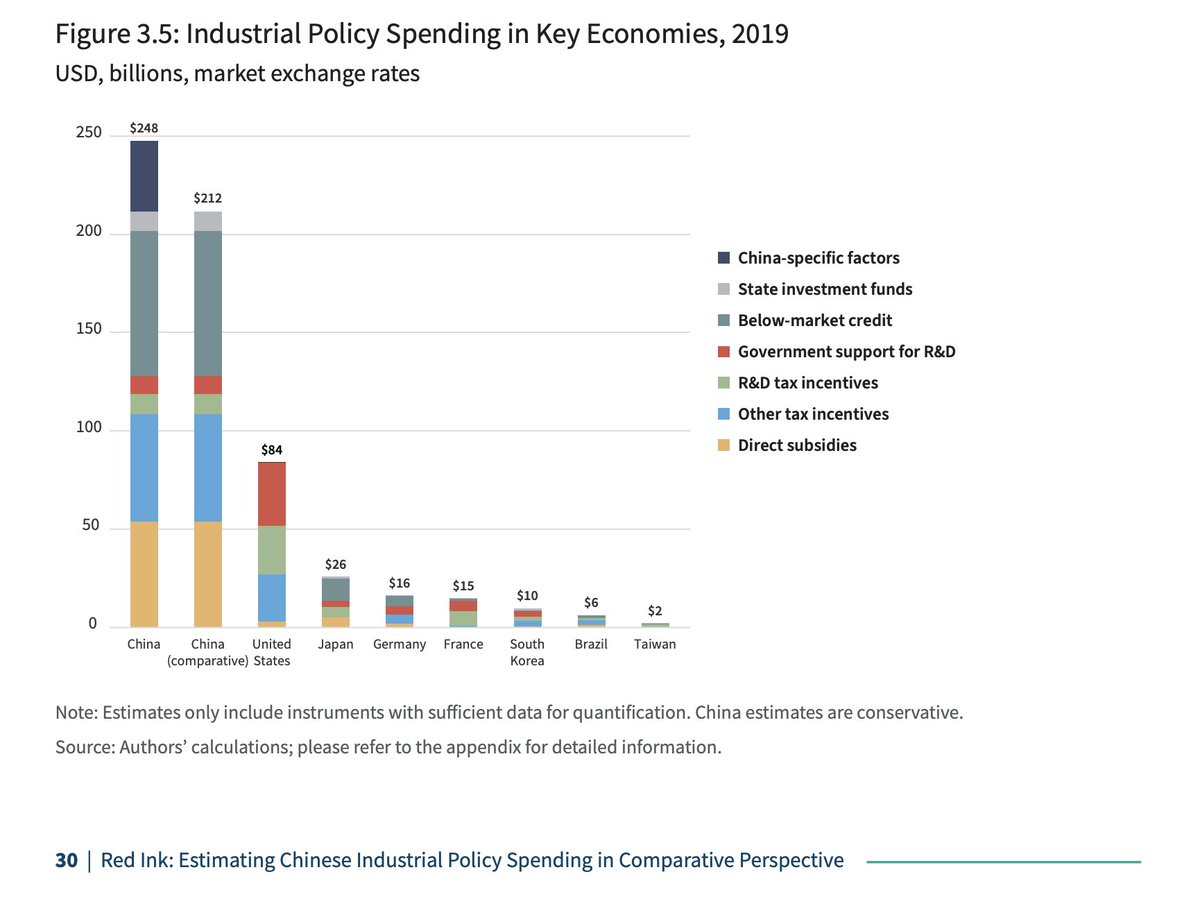

In our framework, governments use IPs to promote high-tech sectors producing tradable goods and services. IPs thus boost the supply of traded goods. When IPs are not balanced by a rise in domestic demand, they cause trade surpluses. Very much what's happening in China.

In our framework, governments use IPs to promote high-tech sectors producing tradable goods and services. IPs thus boost the supply of traded goods. When IPs are not balanced by a rise in domestic demand, they cause trade surpluses. Very much what's happening in China.

My feeling is that this may be a big miss, and that integrating endogenous productivity dynamics in debt sustainability analyses could be an important area for future research.

My feeling is that this may be a big miss, and that integrating endogenous productivity dynamics in debt sustainability analyses could be an important area for future research.

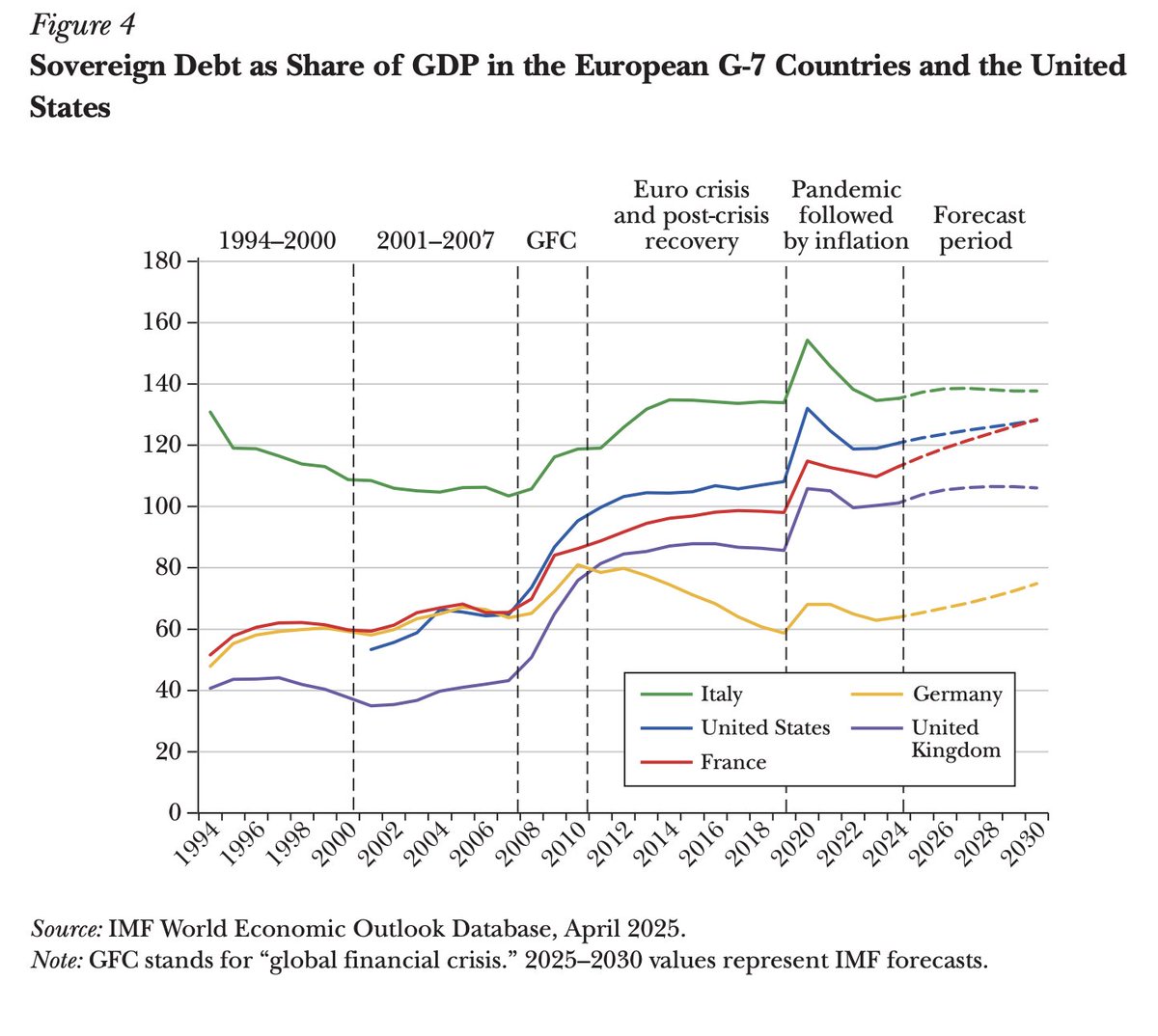

Let's start from Italy. Since the early 1990s, Italy had to post high primary surpluses - high taxes + low public investment - to sustain its public debt. Over this period, productivity growth slowed down dramatically. Will other high-debt countries face a similar scenario?

Let's start from Italy. Since the early 1990s, Italy had to post high primary surpluses - high taxes + low public investment - to sustain its public debt. Over this period, productivity growth slowed down dramatically. Will other high-debt countries face a similar scenario?

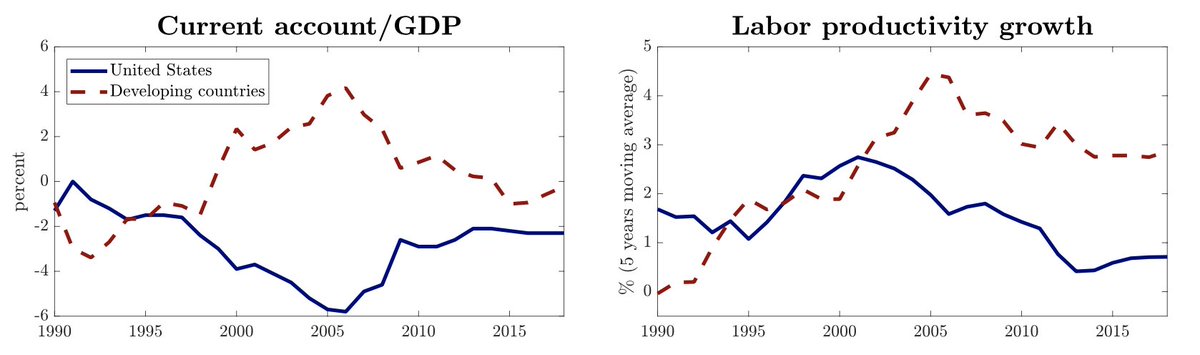

The traditional view is that a country with good growth prospects attracts capital inflows to finance its investment. But in the data the opposite occurs: fast-growing countries run trade surpluses and export capital abroad academic.oup.com/restud/article…

The traditional view is that a country with good growth prospects attracts capital inflows to finance its investment. But in the data the opposite occurs: fast-growing countries run trade surpluses and export capital abroad academic.oup.com/restud/article…

Classic book by @B_Eichengreen on the history of international capital flows, a must read.

Classic book by @B_Eichengreen on the history of international capital flows, a must read.

https://twitter.com/paulkrugman/status/1601628013229400066?s=20&t=LUEatu9BJGVzwJApok39oQ

Empirically, large negative supply shocks - such as hikes in energy prices - are associated with permanent output losses papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…. Fear of these scarring effects is now particularly high in the euro area ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date….

Empirically, large negative supply shocks - such as hikes in energy prices - are associated with permanent output losses papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…. Fear of these scarring effects is now particularly high in the euro area ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date….

Business investment plummeted during the Great Recession, and then recovered slowly. This time is different: strong business investment is a distinguishing feature of the Covid recovery.

Business investment plummeted during the Great Recession, and then recovered slowly. This time is different: strong business investment is a distinguishing feature of the Covid recovery.

that many results can be derived analytically, and can easily be embedded into medium-scale New Keynesian style models. Moreover, the notes touch on themes such as the hysteresis effects from recessions and financial crises, the impact of monetary and fiscal expansions on

that many results can be derived analytically, and can easily be embedded into medium-scale New Keynesian style models. Moreover, the notes touch on themes such as the hysteresis effects from recessions and financial crises, the impact of monetary and fiscal expansions on

I find this fascinating, because when I was in grad school (already more than 10 years ago!) I was taught that business cycles and productivity growth are two independent phenomena, which could be studied in isolation. But then the Great Recession happened...

I find this fascinating, because when I was in grad school (already more than 10 years ago!) I was taught that business cycles and productivity growth are two independent phenomena, which could be studied in isolation. But then the Great Recession happened...

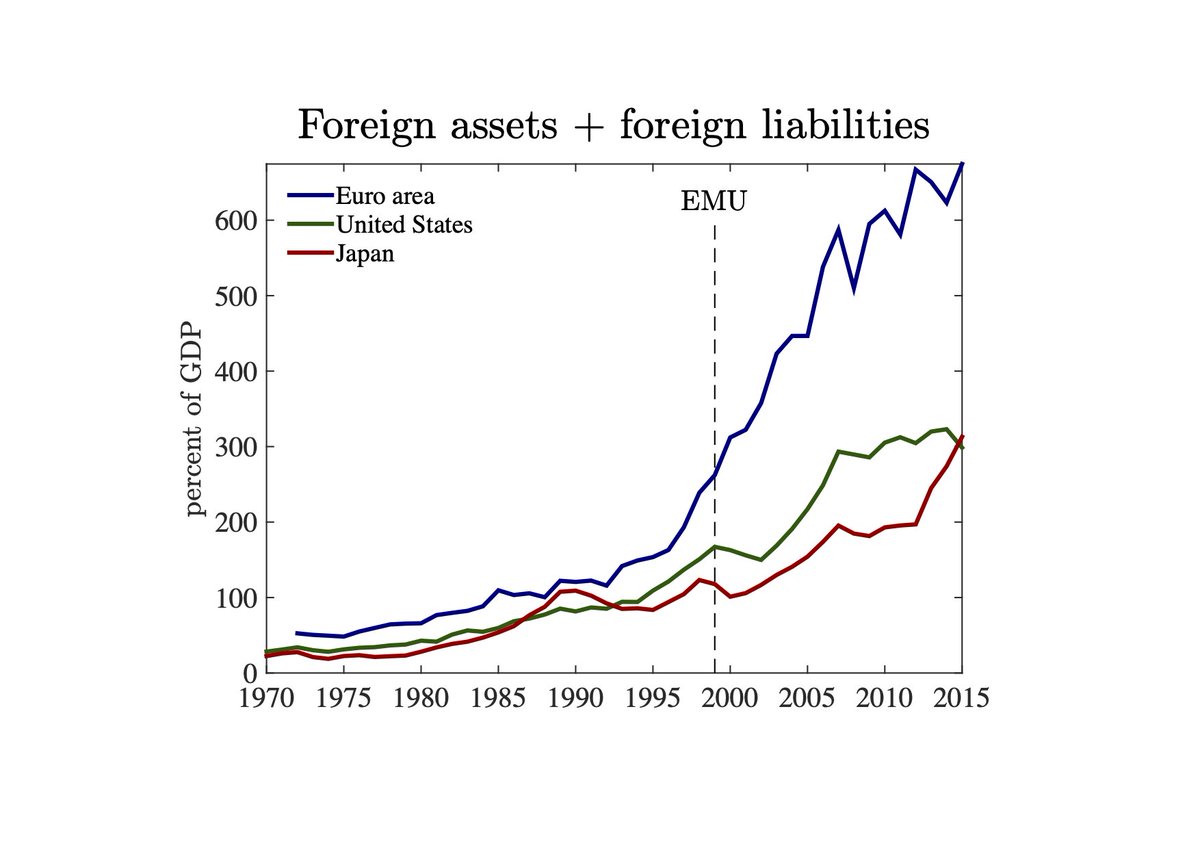

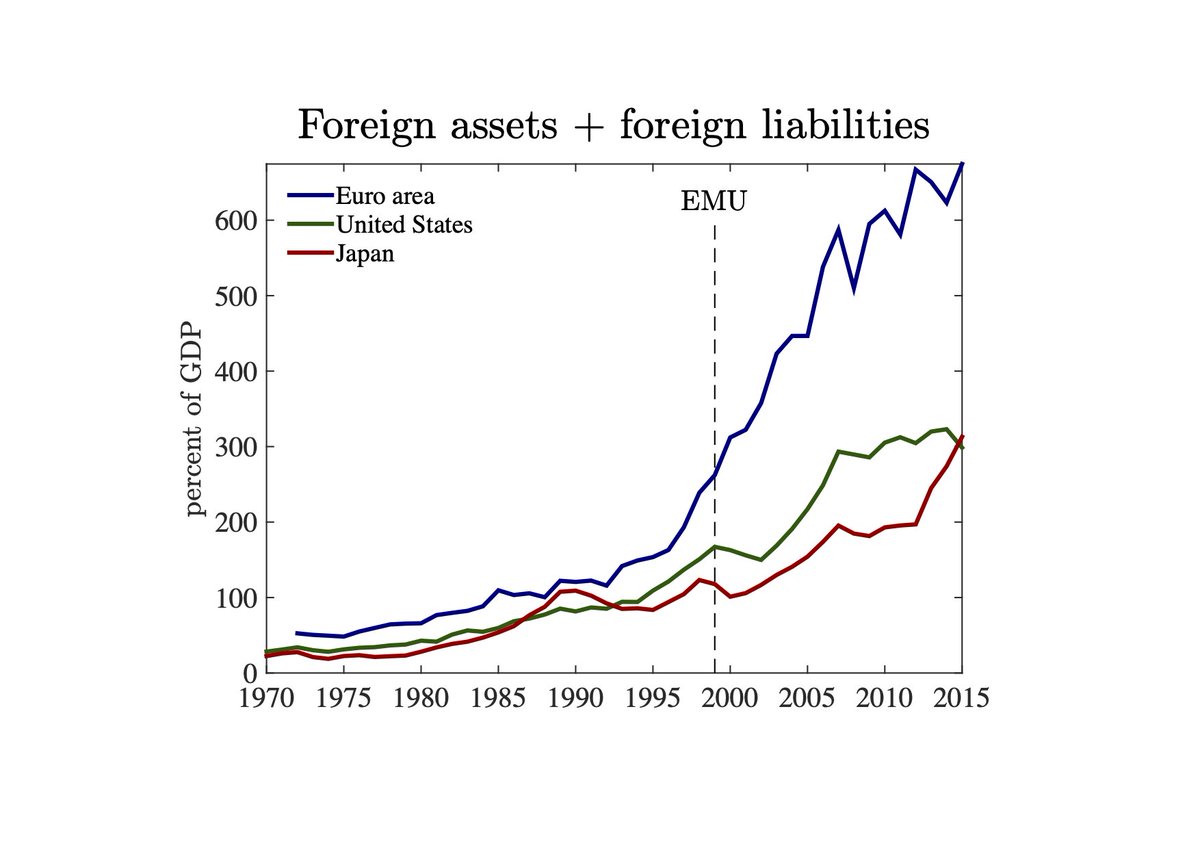

The idea, which goes back at least to Keynes, is that national governments can expropriate foreign creditors by devaluing the exchange rate . Forming a currency union eliminates this possibility, leading to higher capital mobility (crei.cat/wp-content/upl…).

The idea, which goes back at least to Keynes, is that national governments can expropriate foreign creditors by devaluing the exchange rate . Forming a currency union eliminates this possibility, leading to higher capital mobility (crei.cat/wp-content/upl…).

The traditional view - based on the New Keynesian model - is that supply disruptions lead to excessive demand, overheating and inflation above target. The optimal policy response then entails a monetary tightening. But the NK model does not allow for scarring effects.

The traditional view - based on the New Keynesian model - is that supply disruptions lead to excessive demand, overheating and inflation above target. The optimal policy response then entails a monetary tightening. But the NK model does not allow for scarring effects.

We provide a model connecting the global saving glut and productivity growth. Think of a world composed by US and developing countries. Innovation by US firms pushes forward the world technological frontier. Developing countries, instead, grow by absorbing knowledge from the US.

We provide a model connecting the global saving glut and productivity growth. Think of a world composed by US and developing countries. Innovation by US firms pushes forward the world technological frontier. Developing countries, instead, grow by absorbing knowledge from the US.

https://twitter.com/profsufi/status/1272564374599864321?s=20). But the investment response has been lukewarm at best. So why did we see a global saving glut, but not a global investment boom? Here's my take. First, higher saving supply means weaker demand. In turn, weak demand lowers firms' incentives to invest. Due to this effect, an increase in saving supply may lead to a fall in investment and growth! This is what we show in Stagnation Traps (academic.oup.com/restud/article…).

https://twitter.com/jasonfurman/status/1261750314753036291?s=20. To me, especially looking at the post-epidemic phase, a key aspect is how bad the Covid-19 shock is damaging future productive capacity (by making firms scrap their investment plans, companies going bankrupt, destroying worker-firm matches). Some recessions triggered long-lasting supply disruptions and slowdowns in productivity growth, a phenomenon known as hysteresis (voxeu.org/article/persis…, @AntonioFatas).

https://twitter.com/paulkrugman/status/1244965253164793857?s=20Due to the lockdown, households are cutting consumption and increasing savings, making borrowing particularly cheap for the US government. But this logic might not apply to those euro area countries, such as Italy or Spain, most hit by Covid-19.