I promise to be kind and only post about philosophy, science, and animals. 🤞

How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

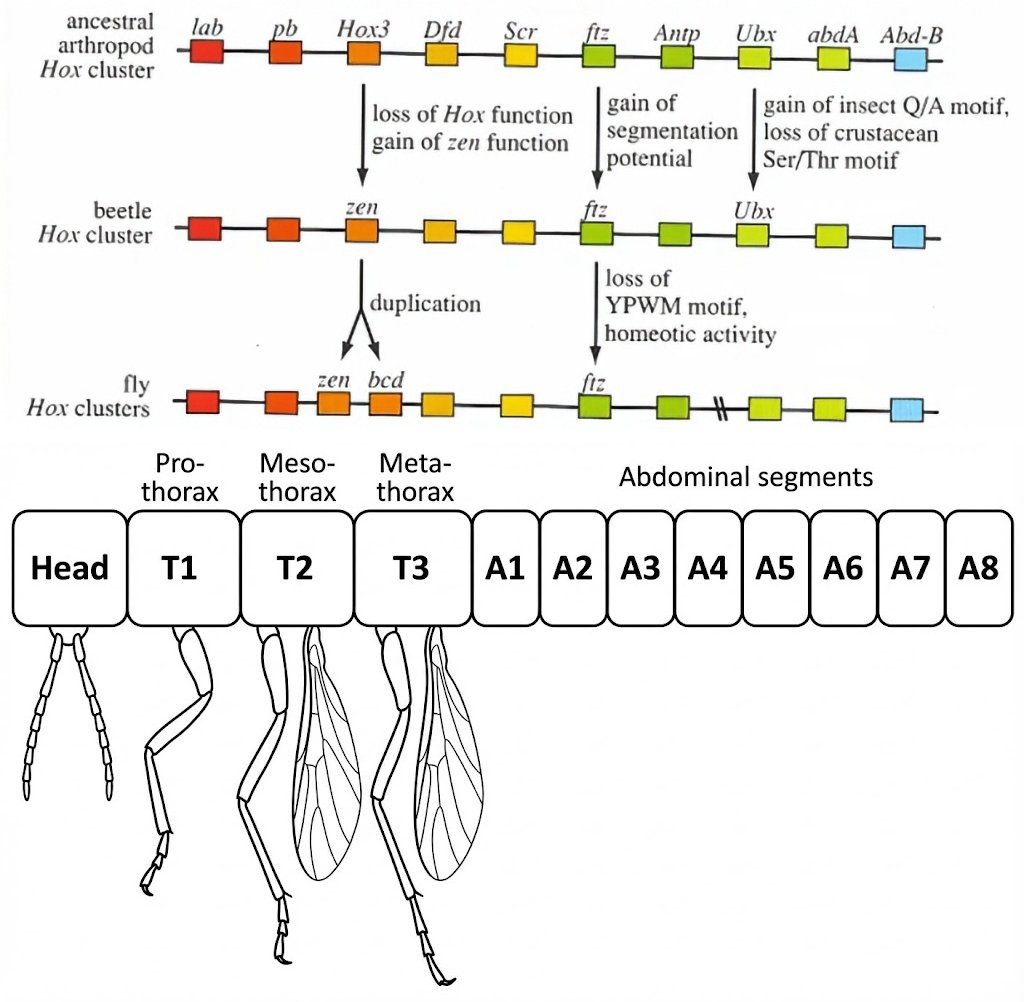

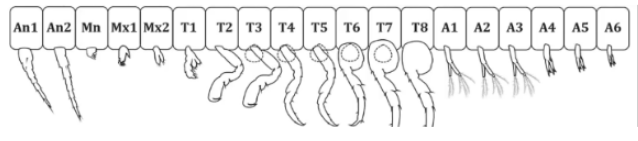

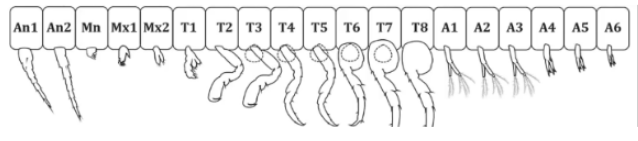

Here you can see the path from the Pancrustacea clade, like our parhyale hawaiensis friend above, to the Hexapoda body plan of flies.

Here you can see the path from the Pancrustacea clade, like our parhyale hawaiensis friend above, to the Hexapoda body plan of flies.