I write things. Uncovering America’s forgotten past. Fact-driven. Lore-obsessed. Mounds, myths, maps. I understand people.

3 subscribers

How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

A river ford.

A river ford.

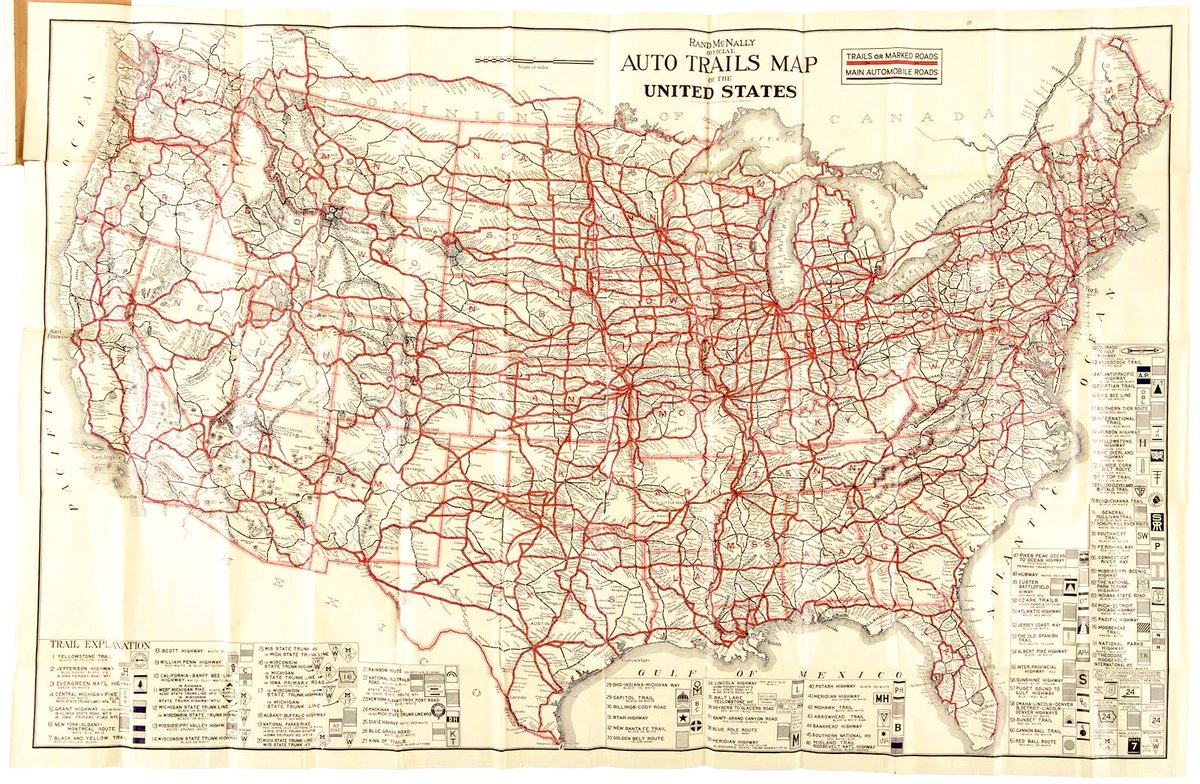

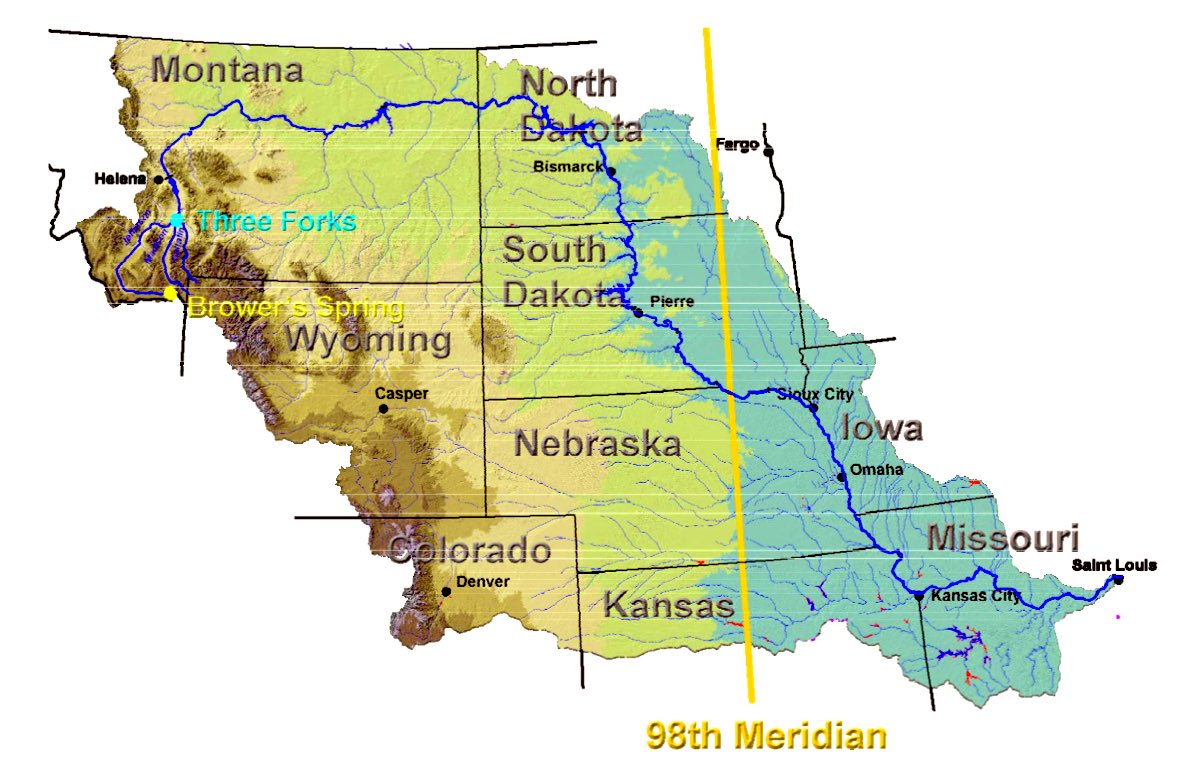

Bison weren’t just wandering the continent.

Bison weren’t just wandering the continent.

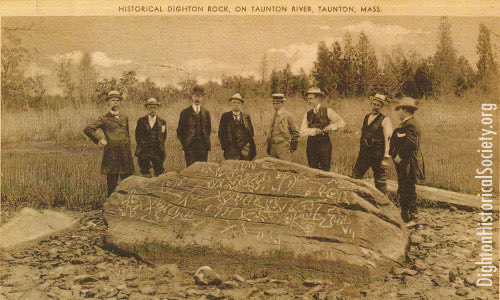

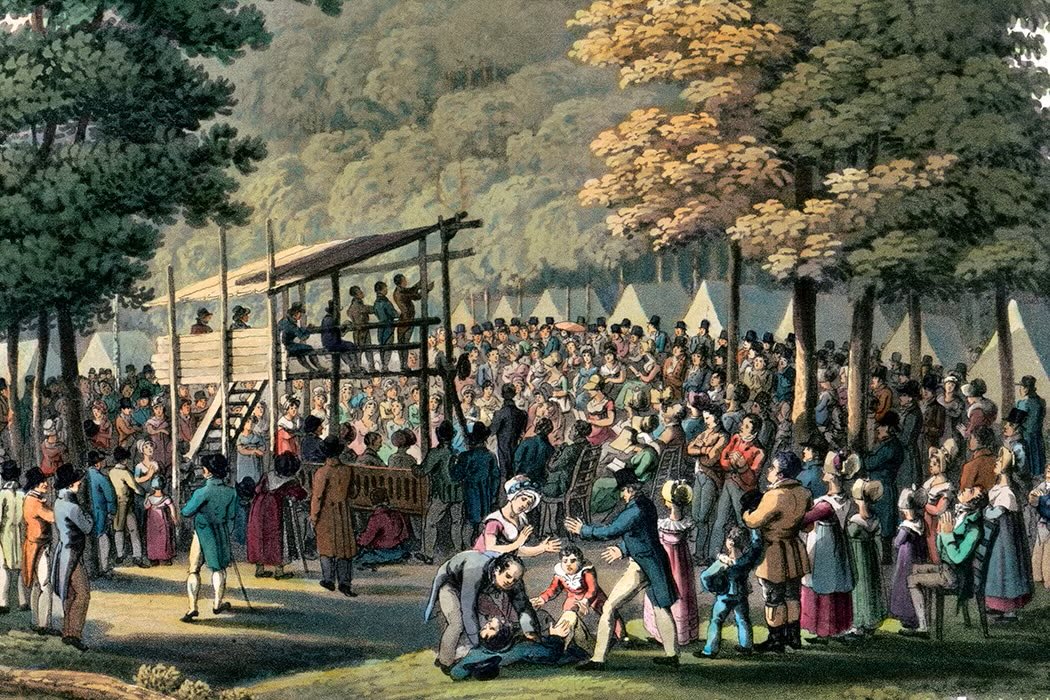

When colonists found it in the 1600s, they couldn’t believe it was Native.

When colonists found it in the 1600s, they couldn’t believe it was Native.

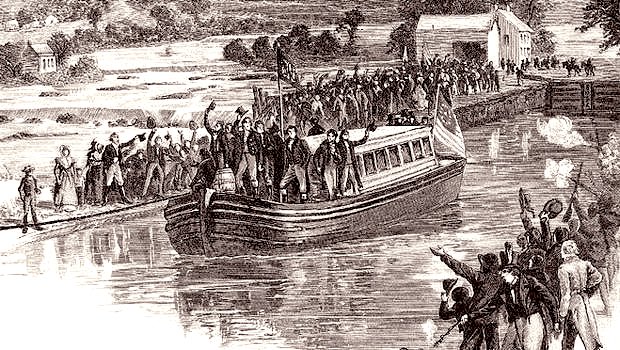

When it reached New York Harbor, that water was poured into the Atlantic.

When it reached New York Harbor, that water was poured into the Atlantic.

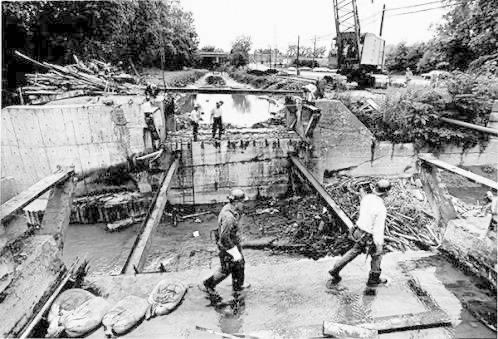

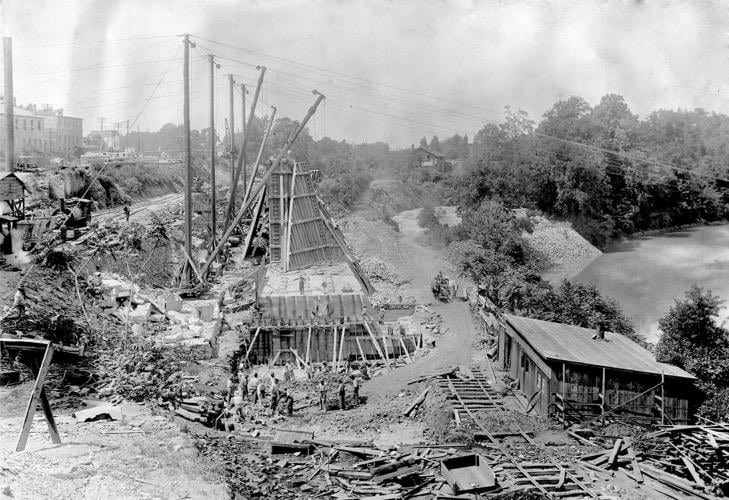

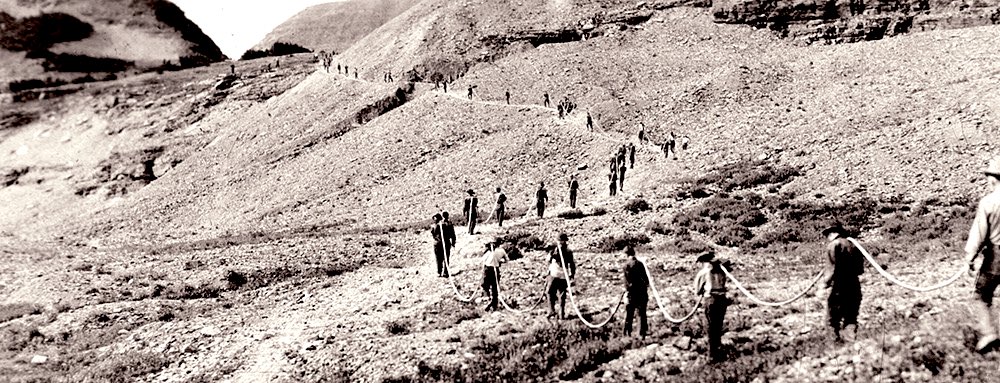

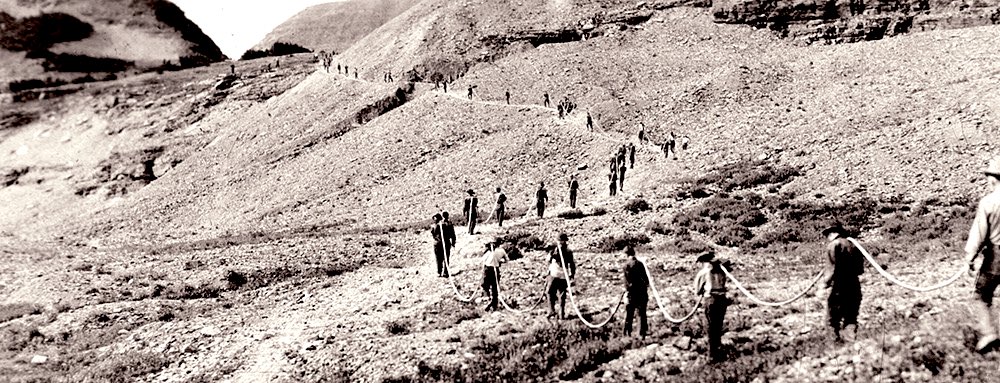

The Erie Canal wasn’t born of machines.

The Erie Canal wasn’t born of machines.

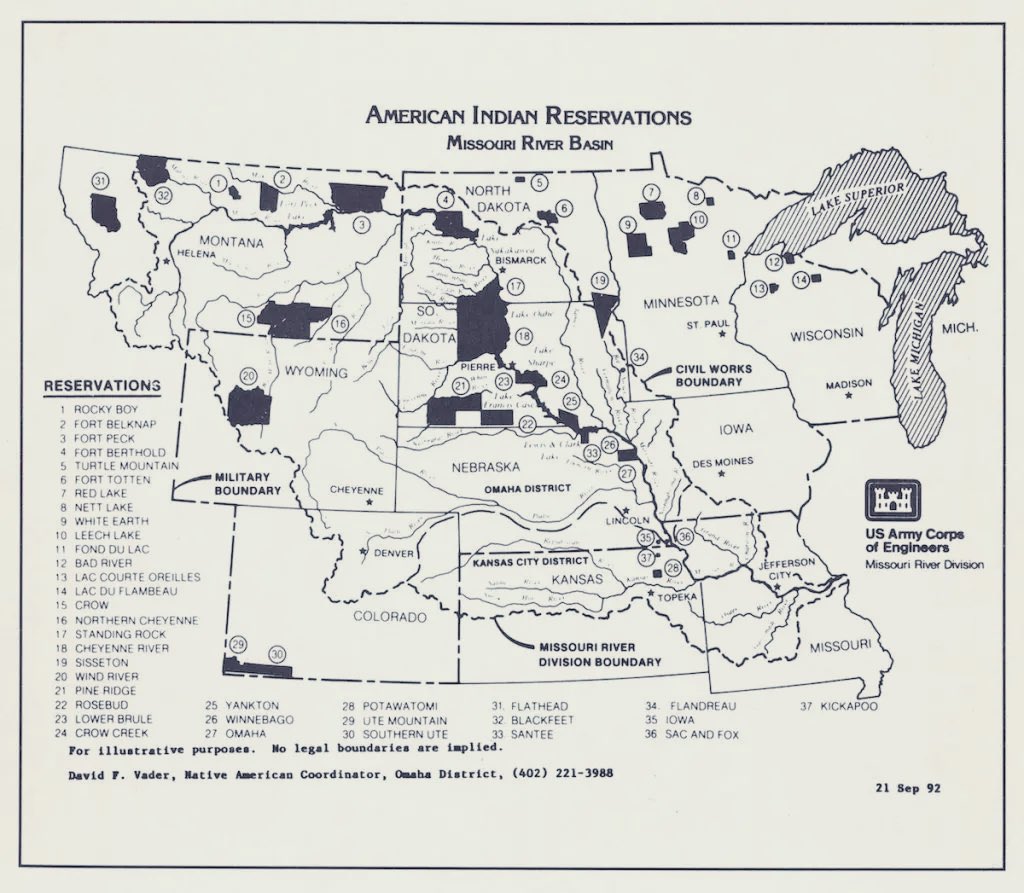

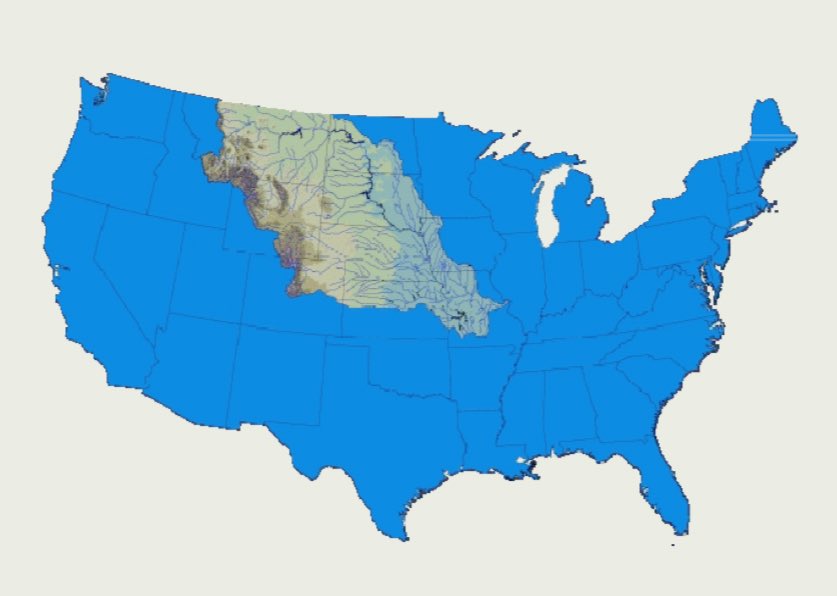

Lake Oahe came from the Pick–Sloan Plan…a postwar promise to “tame” the Missouri.

Lake Oahe came from the Pick–Sloan Plan…a postwar promise to “tame” the Missouri.

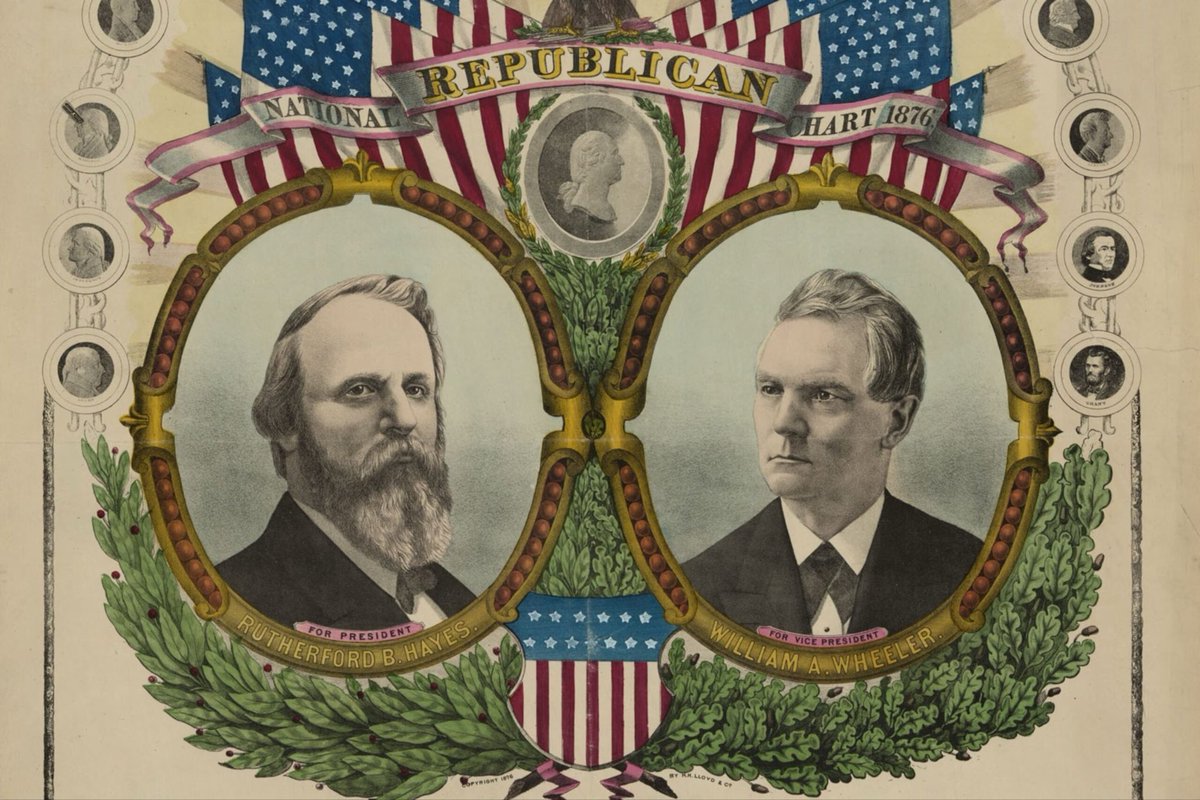

The Civil War was over, but peace wasn’t.

The Civil War was over, but peace wasn’t.

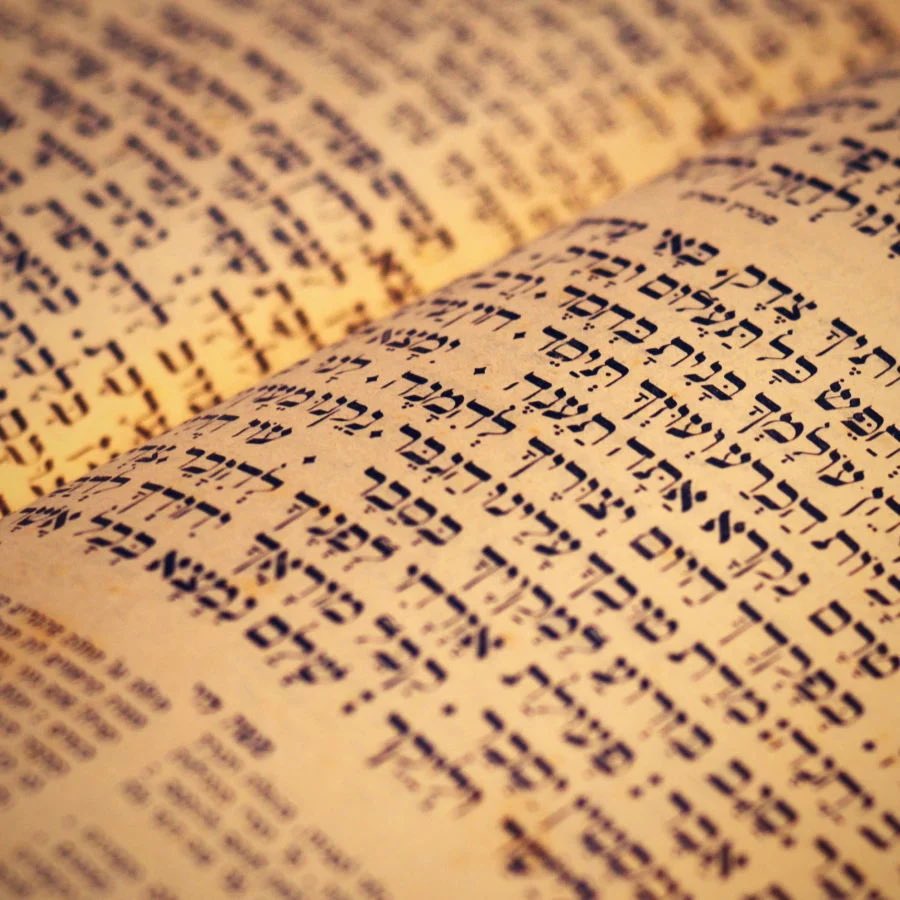

The roots run deep.

The roots run deep.

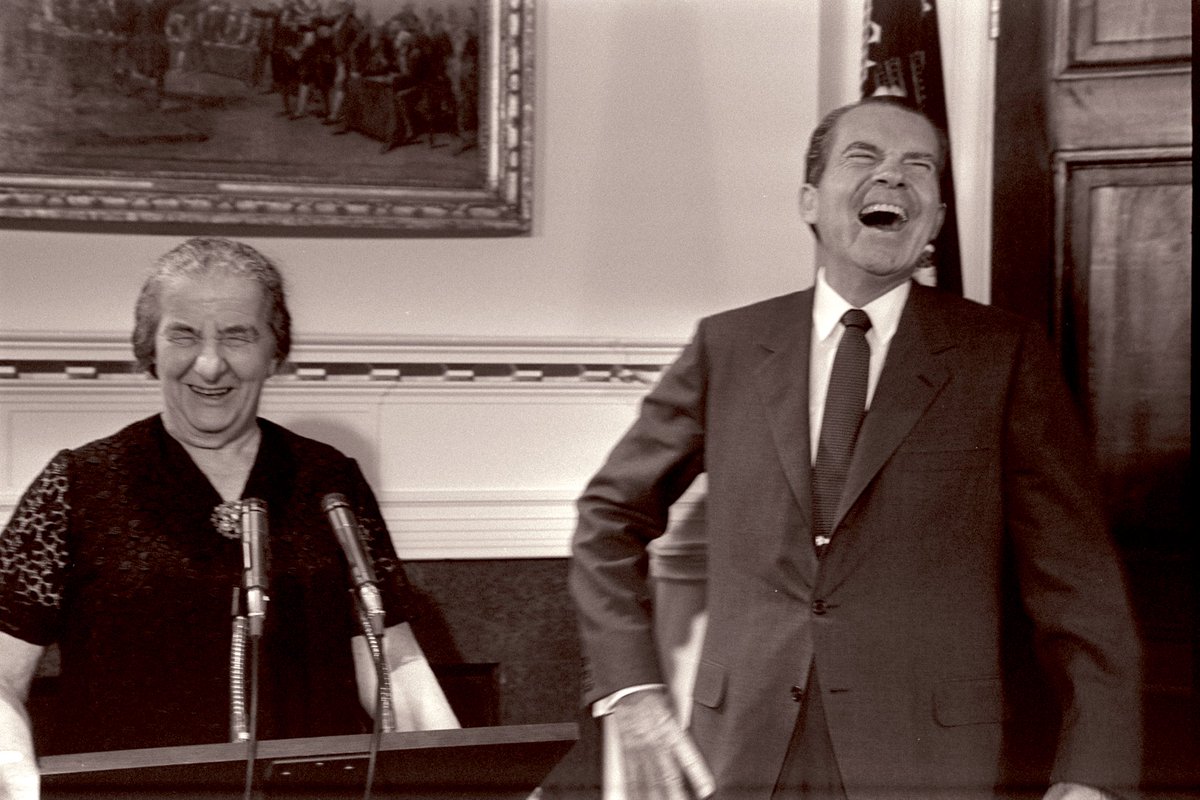

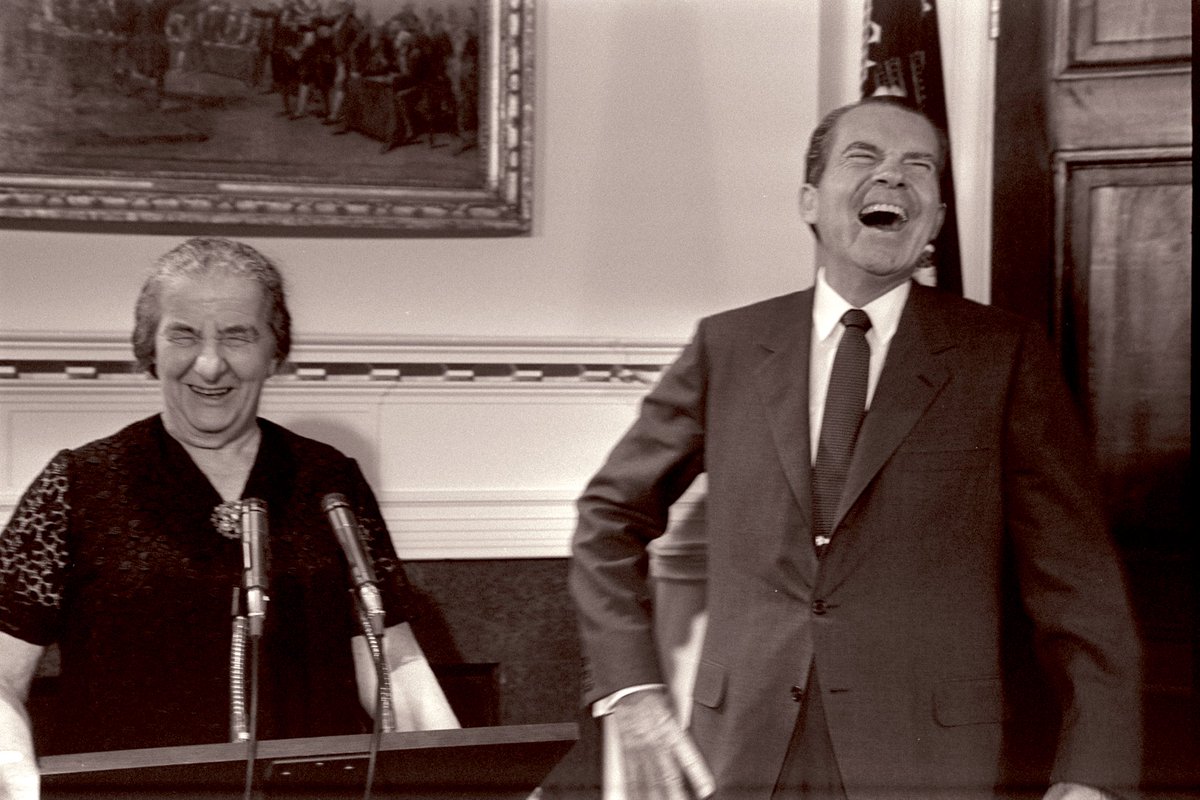

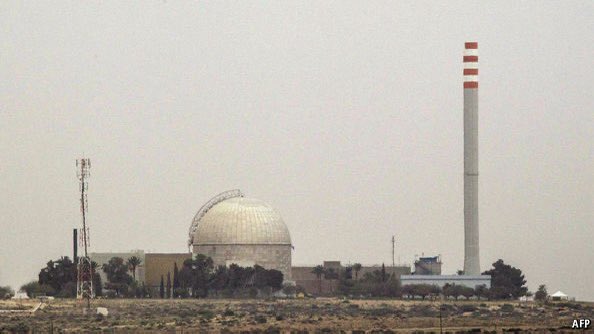

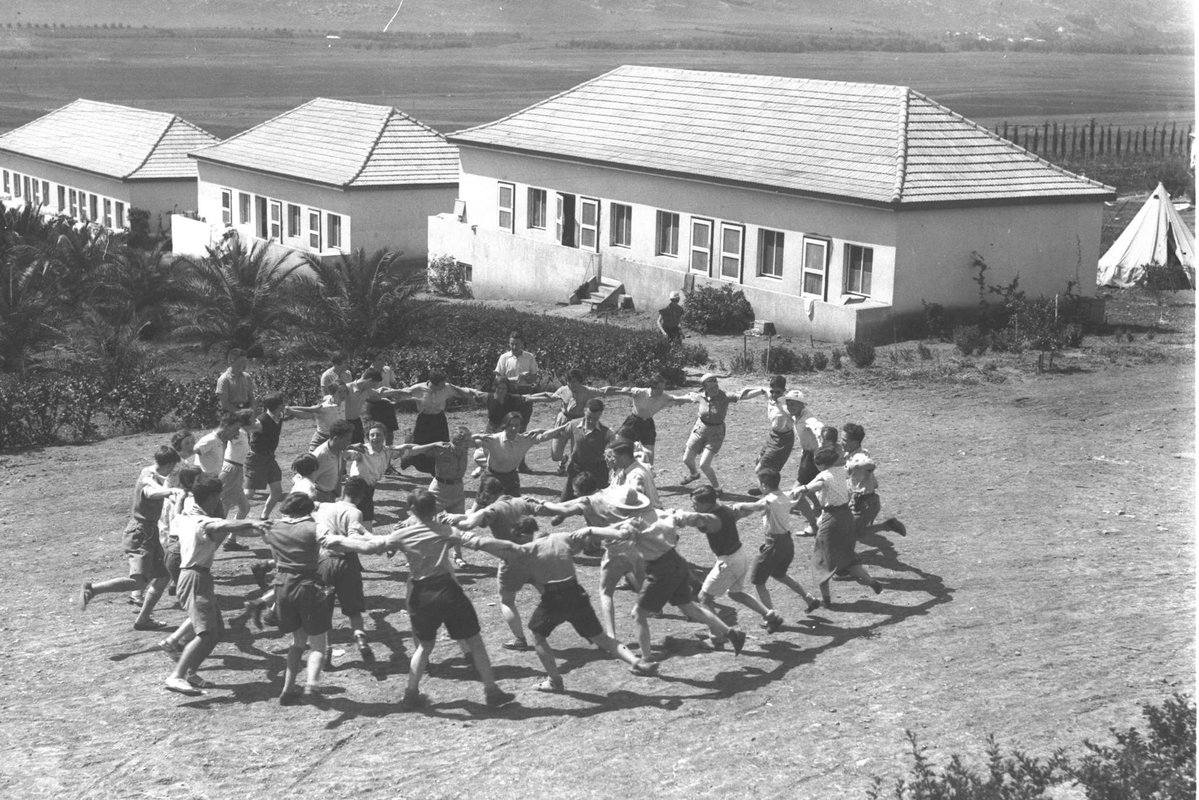

It began in the 1960s at Dimona, in the Negev desert.

It began in the 1960s at Dimona, in the Negev desert.

He named it Taliesin….Welsh for “shining brow.”

He named it Taliesin….Welsh for “shining brow.”

The roots ran deep in America’s imagination.

The roots ran deep in America’s imagination.

Enrollees were 18–25, broke, and hungry.

Enrollees were 18–25, broke, and hungry.

Born in 1734 on Pennsylvania’s frontier, Boone grew up where farm met forest.

Born in 1734 on Pennsylvania’s frontier, Boone grew up where farm met forest.

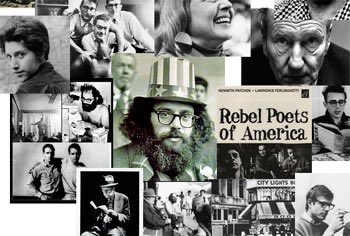

The Beat Generation rose after WWII.

The Beat Generation rose after WWII.

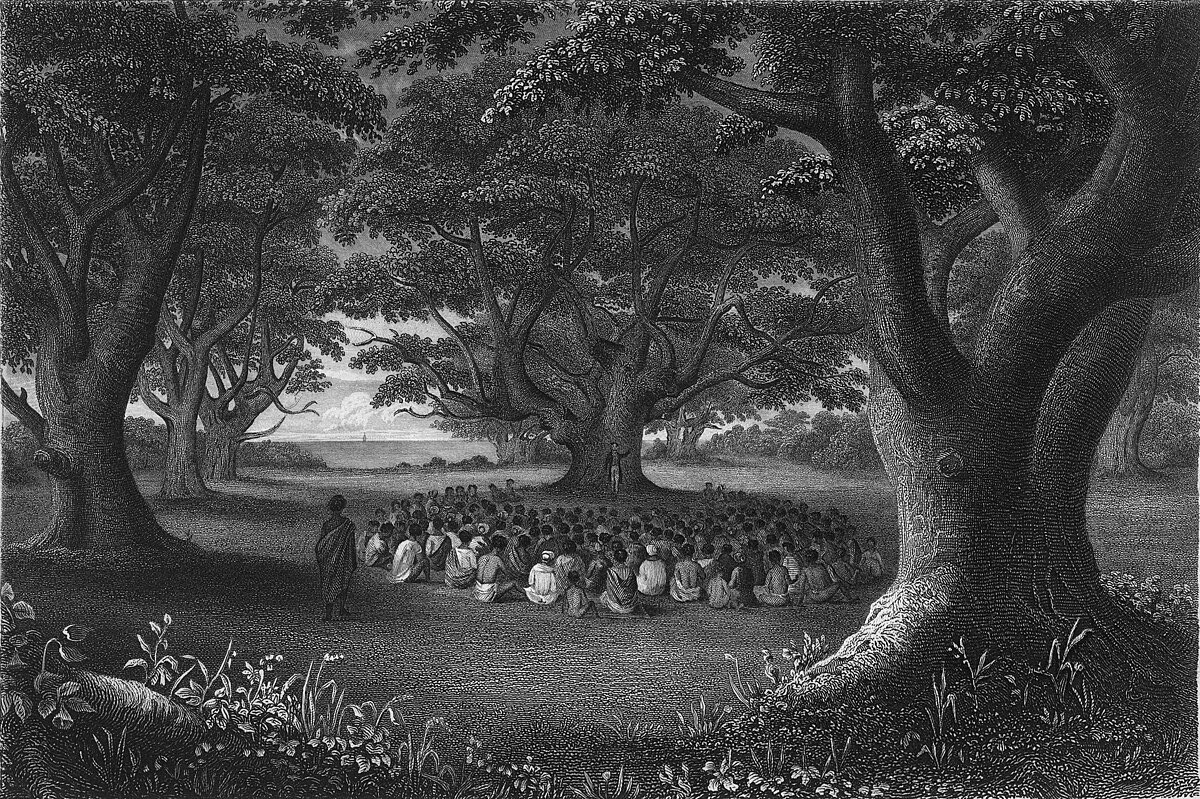

Here, tribes like the Crow, Cheyenne, Shoshone, and Lakota fasted, prayed, and tied offerings.

Here, tribes like the Crow, Cheyenne, Shoshone, and Lakota fasted, prayed, and tied offerings.

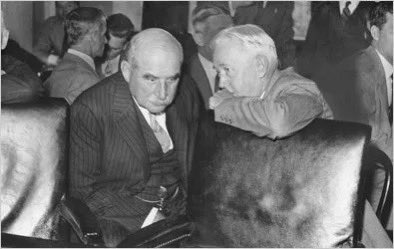

Pecora forced the titans into the Senate chamber:

Pecora forced the titans into the Senate chamber:

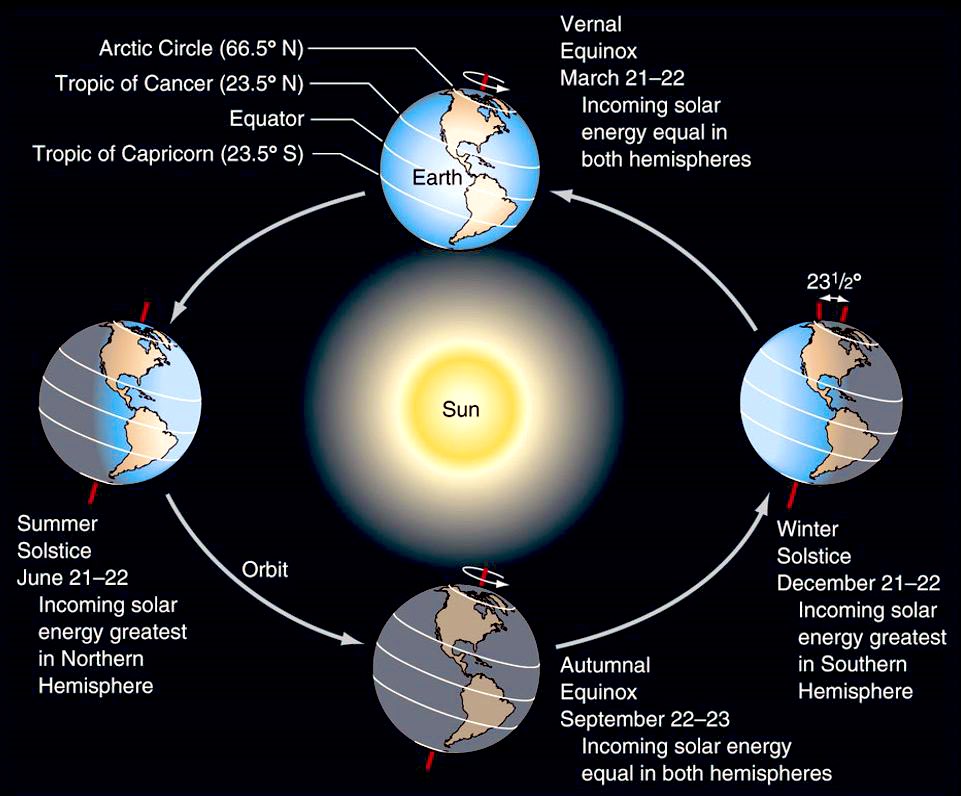

Why does it happen?

Why does it happen?

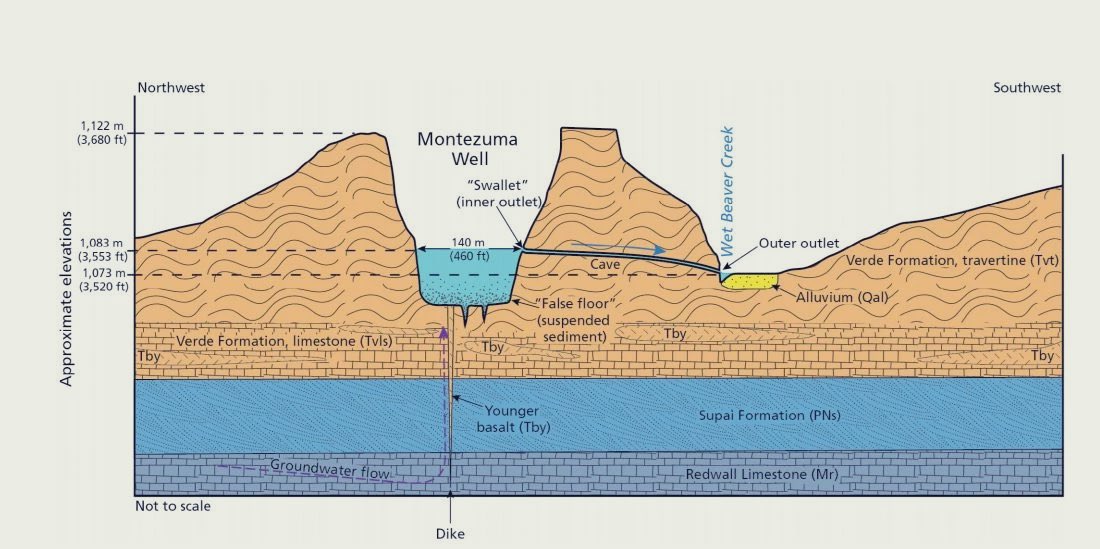

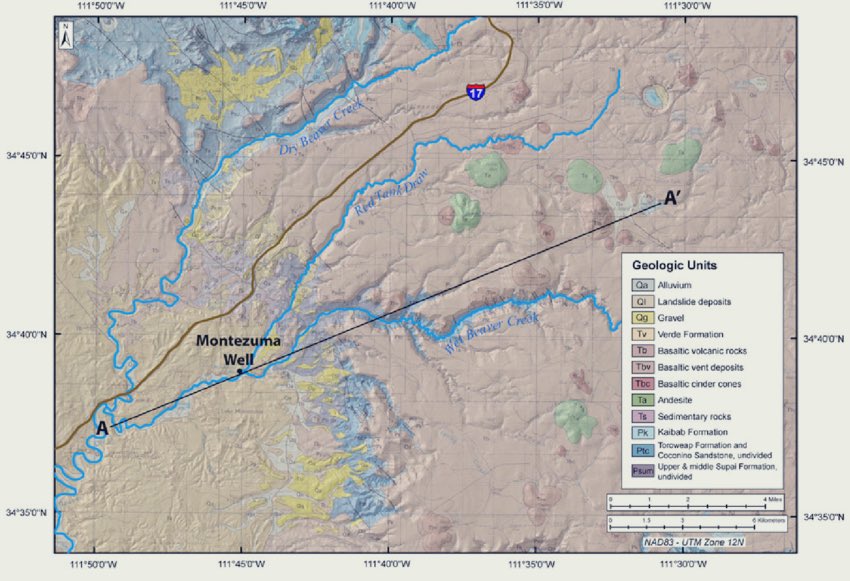

What looks to be crater is actually a collapsed limestone cavern….368 ft wide, 55 ft deep.

What looks to be crater is actually a collapsed limestone cavern….368 ft wide, 55 ft deep.

The memory runs like blood through Paiute history.

The memory runs like blood through Paiute history.

Permafrost isn’t just frozen dirt.

Permafrost isn’t just frozen dirt.

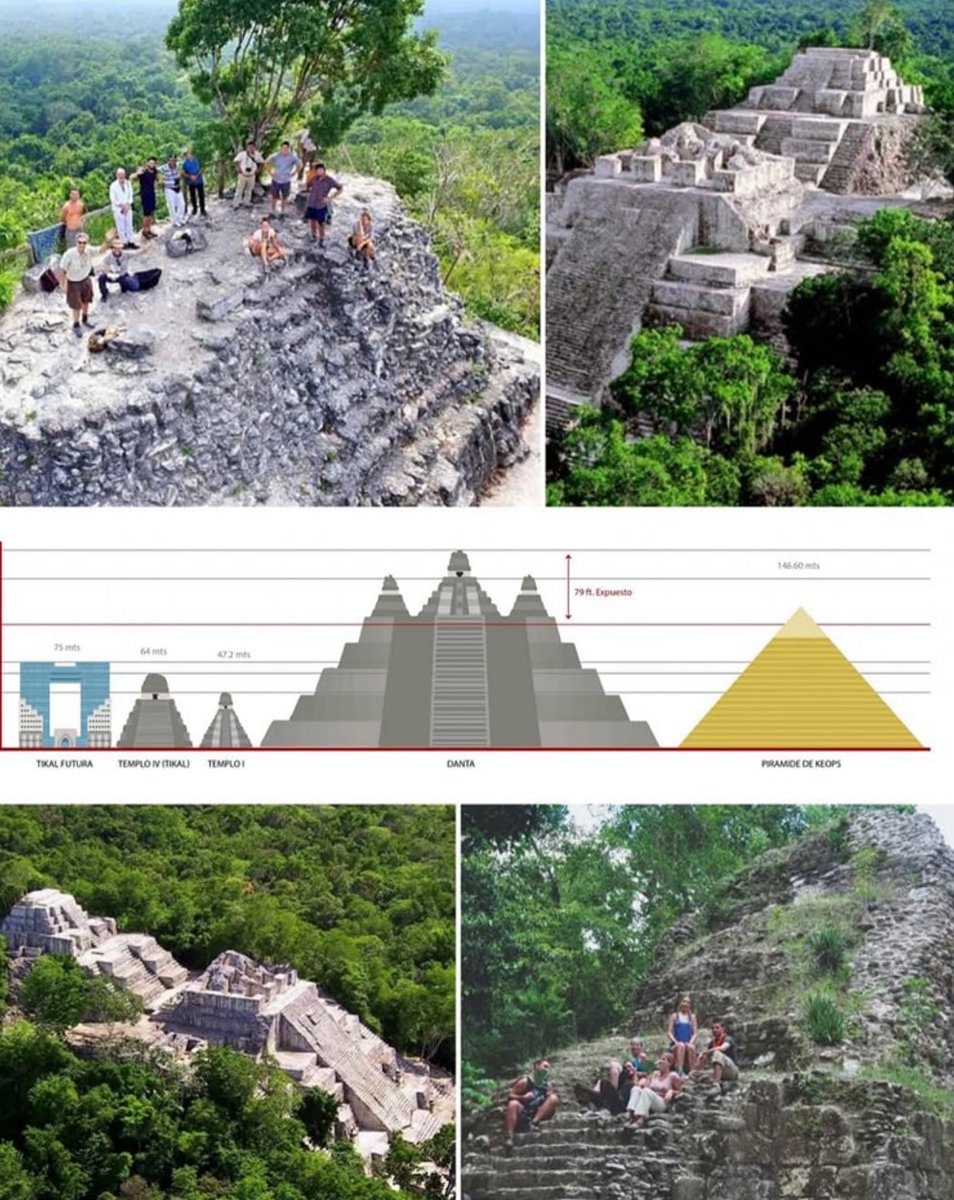

La Danta isn’t just tall (230 ft).

La Danta isn’t just tall (230 ft).