The broad ideology of Marxism has killed roughly 100 million people. It's ghoulish and stupid. Classical liberalism actually works.

7 subscribers

How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

https://twitter.com/rationality1st/status/2015752268004446617Again, the Declaration gives moral clarity about rightful rule, but it does not supply governing capacity. It states legitimacy in first principles: consent, natural rights, just governance, and the right to alter a predatory regime. It is a standard, not a machine. It judges power with moral force. But it does not tell you how those limits stay binding on Tuesday afternoon when passions run high, money runs short, factions scheme, and rivals probe for weakness.

https://twitter.com/SwipeWright/status/2012745051420389548You can thank @thepalmerworm for the snappy phrase “ontological and teleological inversion.” It packs the whole template into four words.

https://twitter.com/Ne_pas_couvrir/status/2002495125210210743The Thesis is Marx’s intellectual evolution can be traced as a shift in the meaning of “practice.” He moves from the Young Hegelian notion of critique as practice (the idea that theoretical criticism itself is a world-changing force) to Moses Hess’s notion of praxis as deed, a fusion of thought and organized action aimed at repairing social estrangement, and finally to Marx’s own materialist recoding of that praxis. Crucially, Marx preserves much of Hess’s functional architecture of alienation and reintegration even as he rejects Hess’s mystical or ethical idiom (what Marx and Engels later dismiss as “True Socialism”).

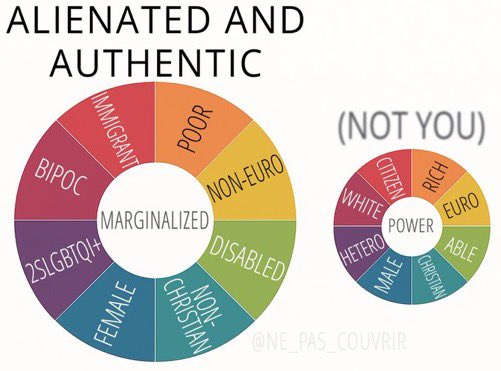

https://twitter.com/ne_pas_couvrir/status/2008503231148933123Alienation is the theory that makes inversion feel true here for the foot soldiers. It trains people to experience human-made realities, money, institutions, norms, and “structures,” as external forces that rule them. Once that move lands, frustration becomes victimhood, opponents become aggressors, and activism becomes moral duty. Activism is life lived inside that inverted map. Praxis is the offensive move sold as rescue and repair. Alienation sells the story. The victim-offender reversal weaponizes it. Praxis executes it.

https://x.com/Ne_pas_couvrir/status/2006845683853042167Mind turn: Descartes and the posture of withdrawal

https://x.com/Ne_pas_couvrir/status/1693045691377946972Stage one: Unity consciousness and contraction.

https://x.com/Ne_pas_couvrir/status/1997140629399523667Where does "left" & "right" actually come from?

The core argument, put simply is, before Luria, most mystical and philosophical traditions imagined reality as a smooth flow from God to the world (like a pyramid with God at the top). Luria dramatically reversed this: God had to withdraw completely to create space for anything else to exist.

The core argument, put simply is, before Luria, most mystical and philosophical traditions imagined reality as a smooth flow from God to the world (like a pyramid with God at the top). Luria dramatically reversed this: God had to withdraw completely to create space for anything else to exist.

https://x.com/Ne_pas_couvrir/status/1979944825827778796Hess inherits this Lurianic-infused Hegelian framework, blending it with Spinoza's monism from the Ethics, which treats thought and extension as modes of a single substance and informs Hess's vision of a reconciled community. While Kant's regulative teleology in the Critique of Judgment and his providential view of history in the 1784 "Idea for a Universal History with a Cosmopolitan Aim" provide a background for seeing progress as purposeful (albeit antagonistic), Hess anchors this teleology in human agency, secularizing it into praxis through his "philosophy of the deed" and making communal reconciliation the product of conscious action rather than inevitable unfolding (Hess, "Philosophie der Tat"; Avineri).

https://x.com/Ne_pas_couvrir/status/1974603374147342747The opening move is a narrowing that makes historical room, followed by a break in the ordering of things that leaves a residue. This process is internal within (the Geist, the oneness), and the framework is explicit re; the internality of this process and the persistence of a trace after contraction; this explains how fragments can still bear the mark of the source even in a damaged field.

https://twitter.com/AOC/status/1969074559602110509

The meme is undefeated.

The meme is undefeated. https://twitter.com/johnpavlovitz/status/1969103912981434603

Fast forward a few years, and you have a clash between Northern and Deep South interests.

Fast forward a few years, and you have a clash between Northern and Deep South interests.

https://twitter.com/FedPoasting/status/1810392510277235013So, what exactly is framing? At heart, it's a mental and communication trick where people, groups, or the media pick and choose how to package information. This influences how you perceive it, make sense of it, and react. In psychology, it's called the framing effect, a kind of bias where the way something's worded or presented, like focusing on the upside versus the downside, nudges your choices without altering the facts. It plays on quick brain shortcuts, making one side feel way more attractive. In broader fields like communication and social studies, framing builds whole stories by spotlighting some details, such as who caused a problem, the moral takeaway, or the fix, while shoving others into the shadows or cutting them out completely. Think of it like a picture frame: it highlights the main scene, draws your eye to certain colors, and crops out distractions, guiding your emotions and actions while setting boundaries on what's acceptable to talk about.

https://twitter.com/Ne_pas_couvrir/status/1927436205911683462

From a Game Theory POV

From a Game Theory POVhttps://twitter.com/Ne_pas_couvrir/status/1930691093370474808Greek Magical Papyri (c. 2nd c. BC (ish)