Founder @algxtradingco; TG: https://t.co/LMpThmUgWk TV: https://t.co/QKr8ST4wPQ YT: https://t.co/DaRiDWDDcK

How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

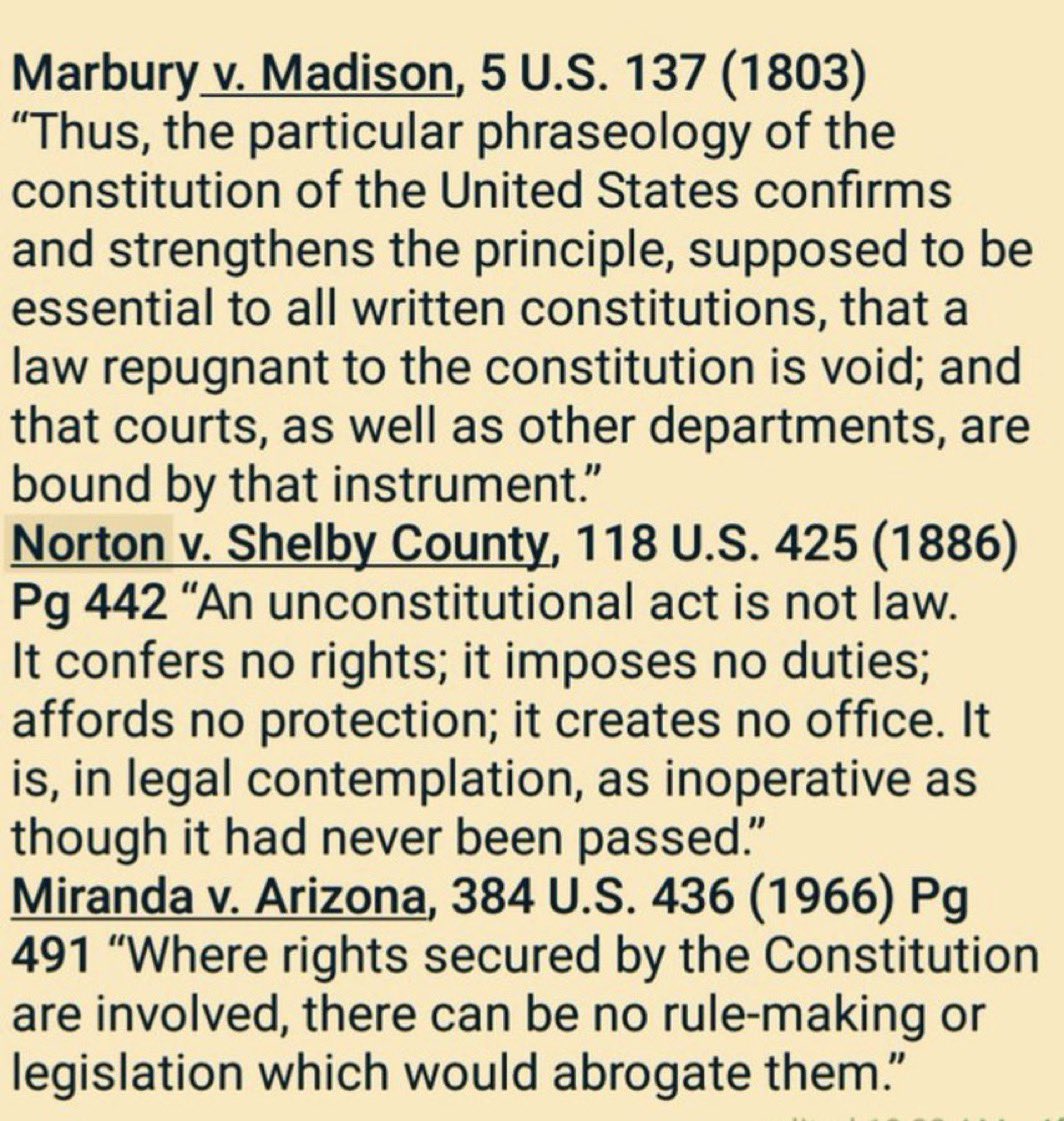

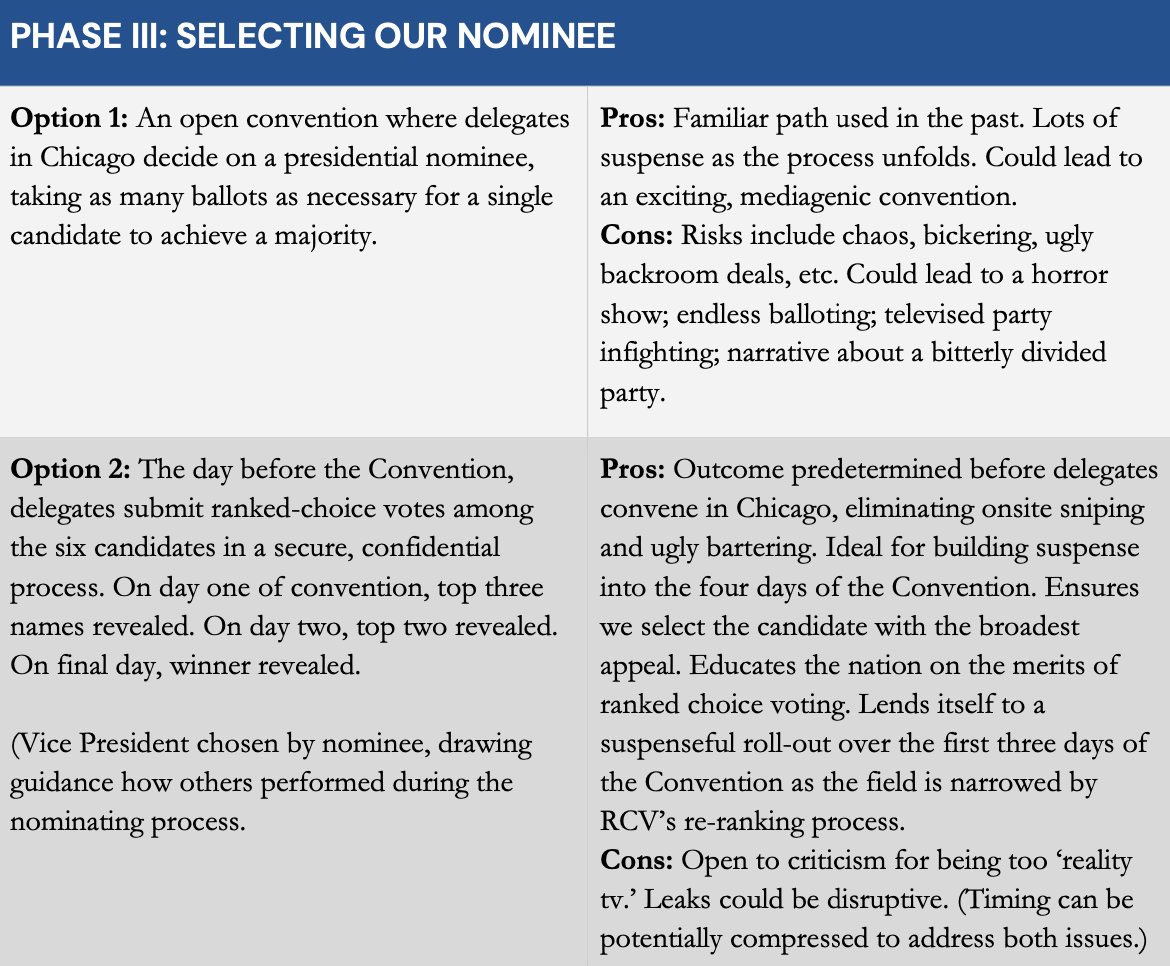

Panel I — The Gate that Pretends to be a Wall

Panel I — The Gate that Pretends to be a Wall

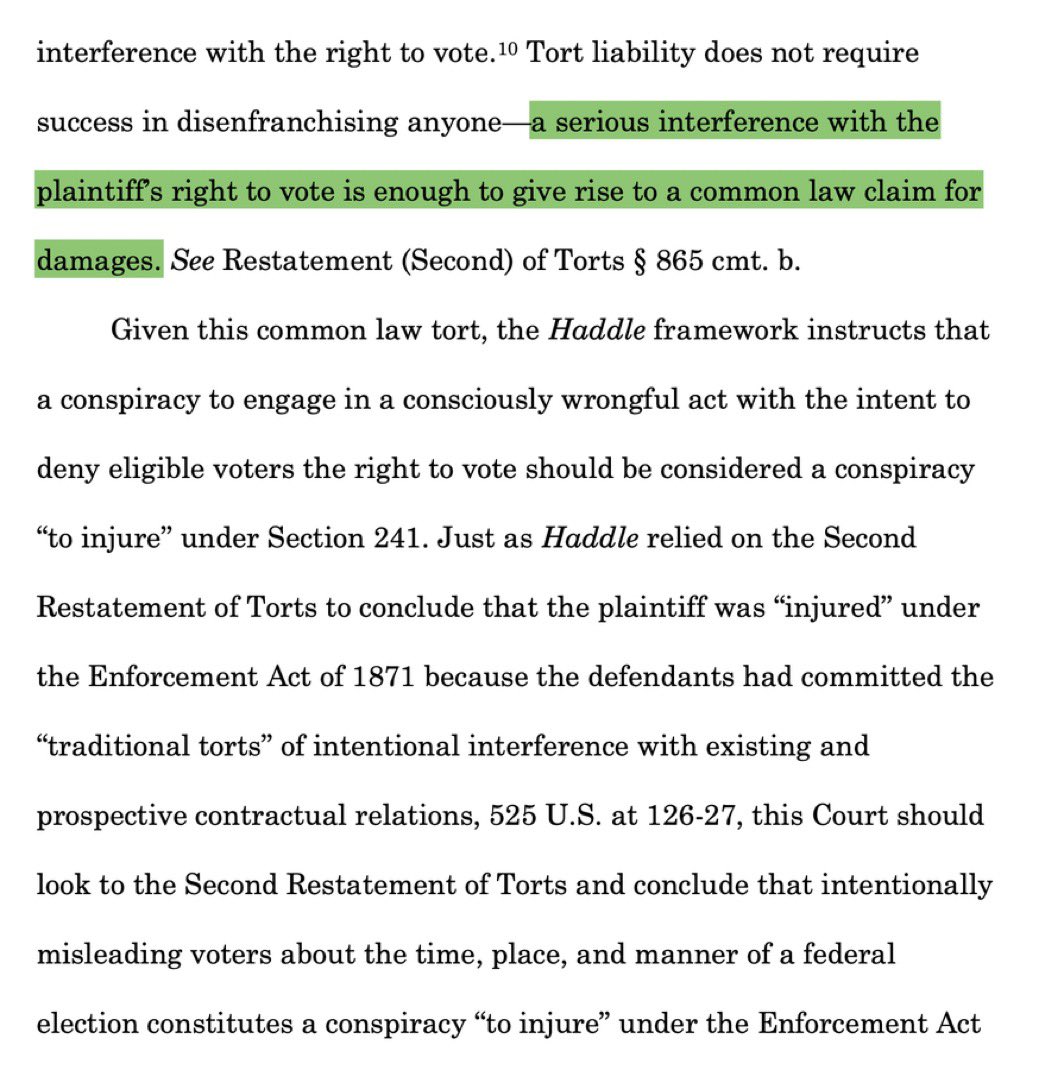

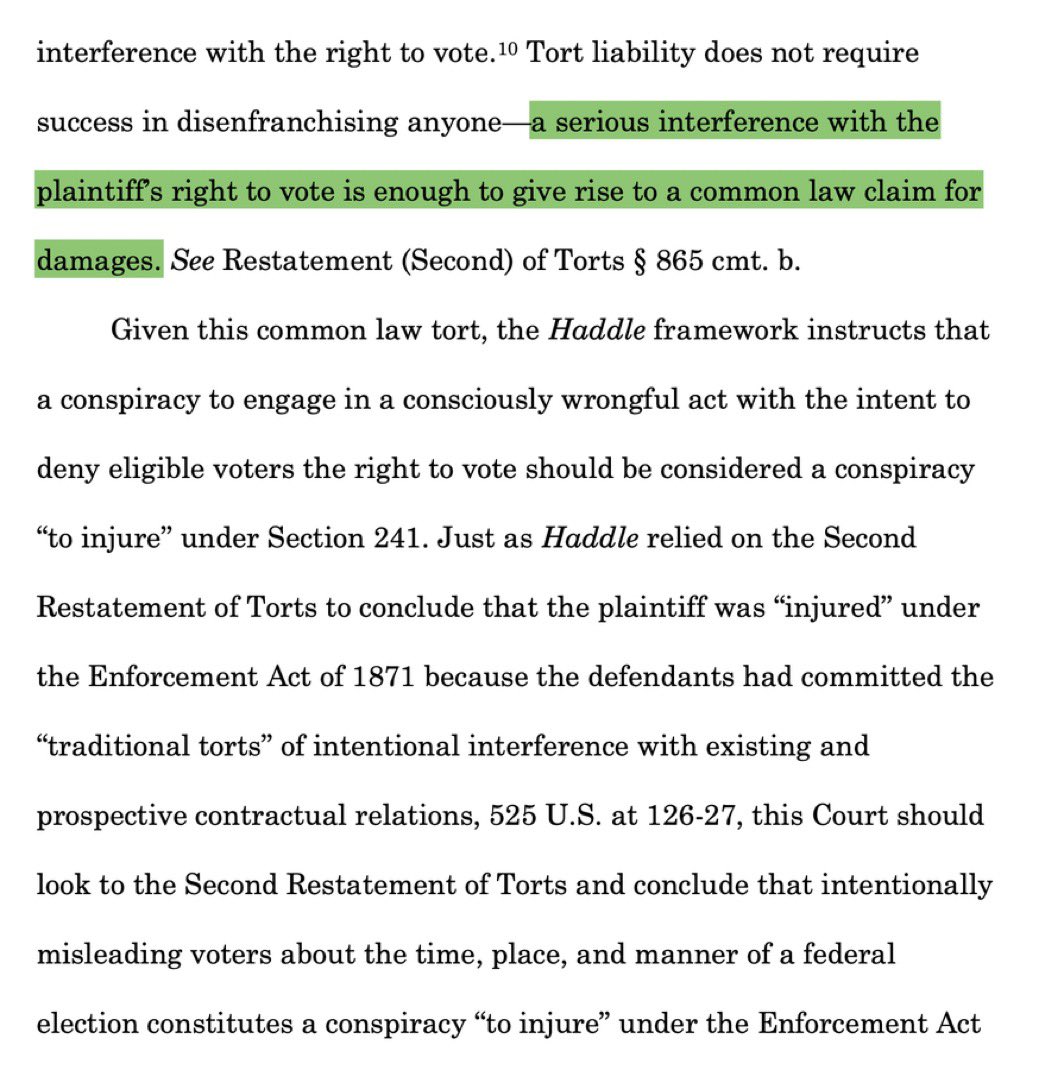

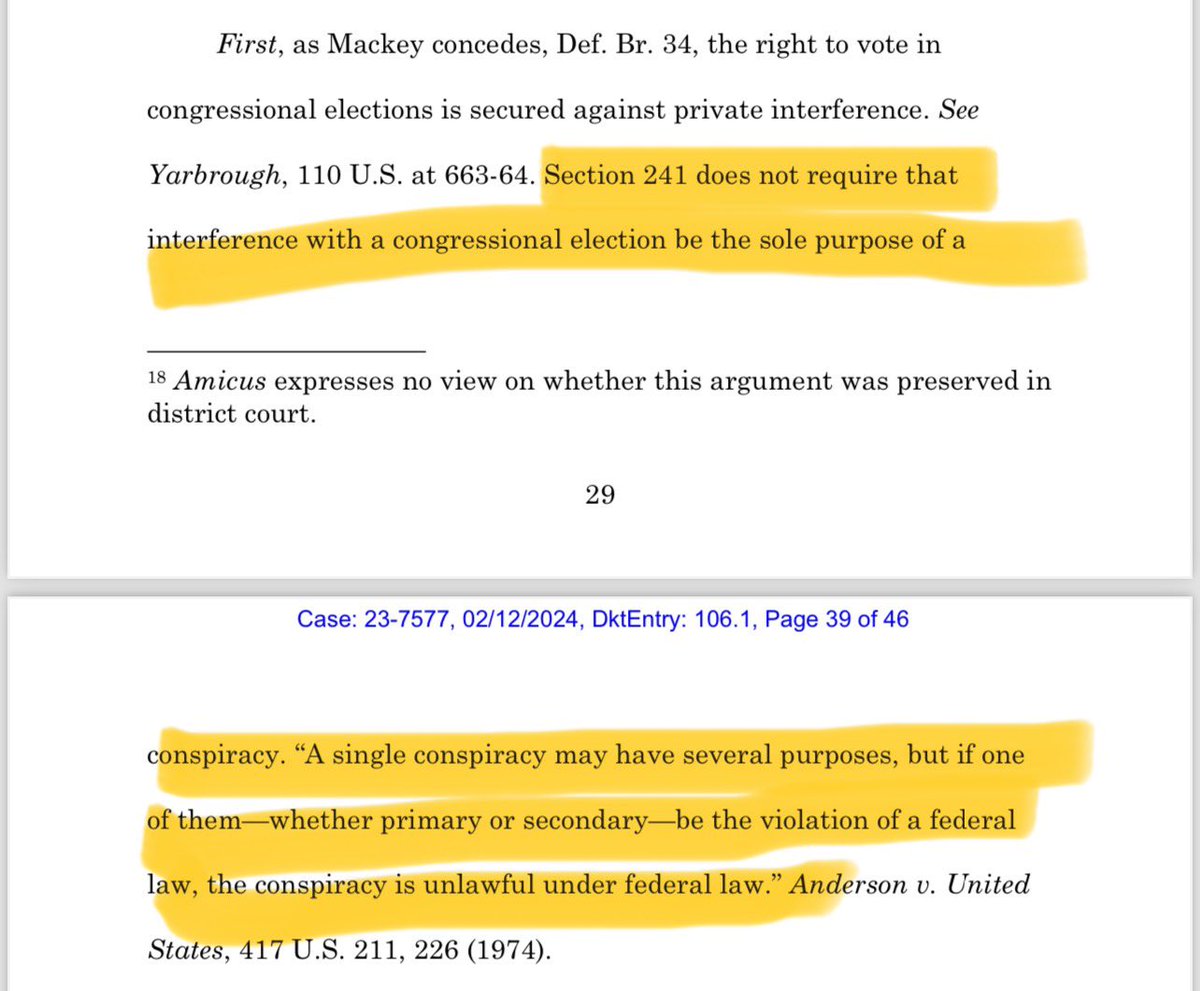

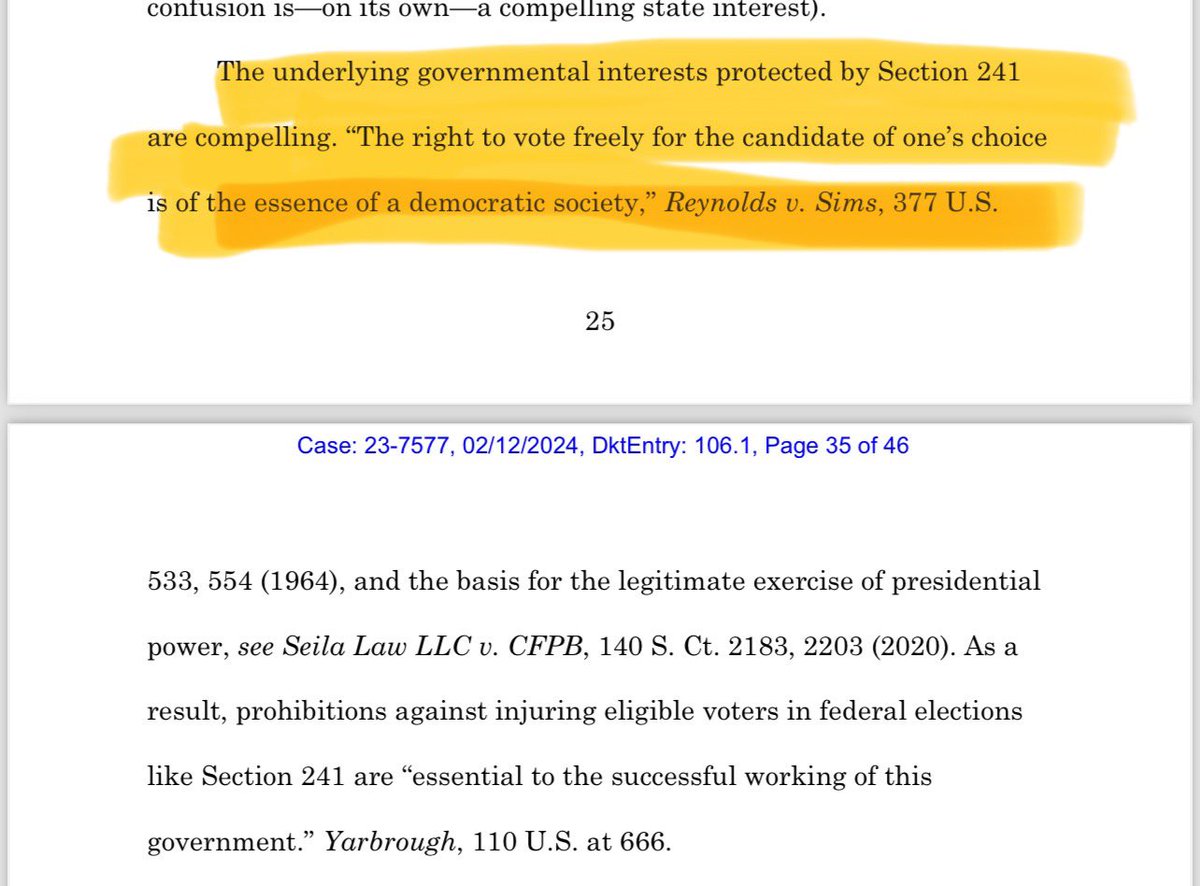

Serious Interference

Serious Interference

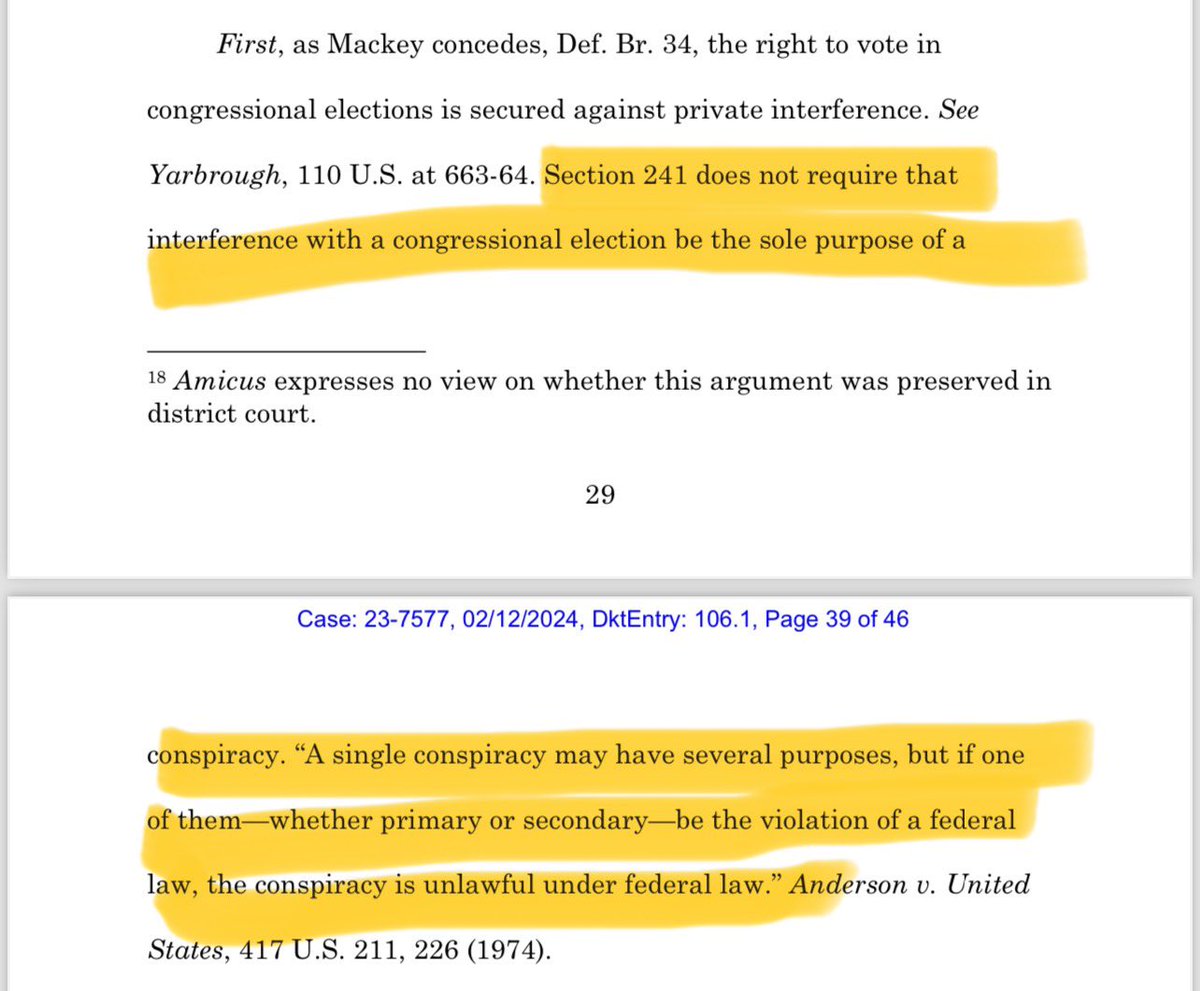

I. Antitrust Violations

I. Antitrust Violations

@julie_kelly2 This is the partial novel prosecutorial theory. This is around 300 pages long, and it’s just the outline. This is very detailed, but it includes nearly everything that would be needed for prosecution.

@julie_kelly2 This is the partial novel prosecutorial theory. This is around 300 pages long, and it’s just the outline. This is very detailed, but it includes nearly everything that would be needed for prosecution. https://twitter.com/algxtradingx/status/1802491148021408180

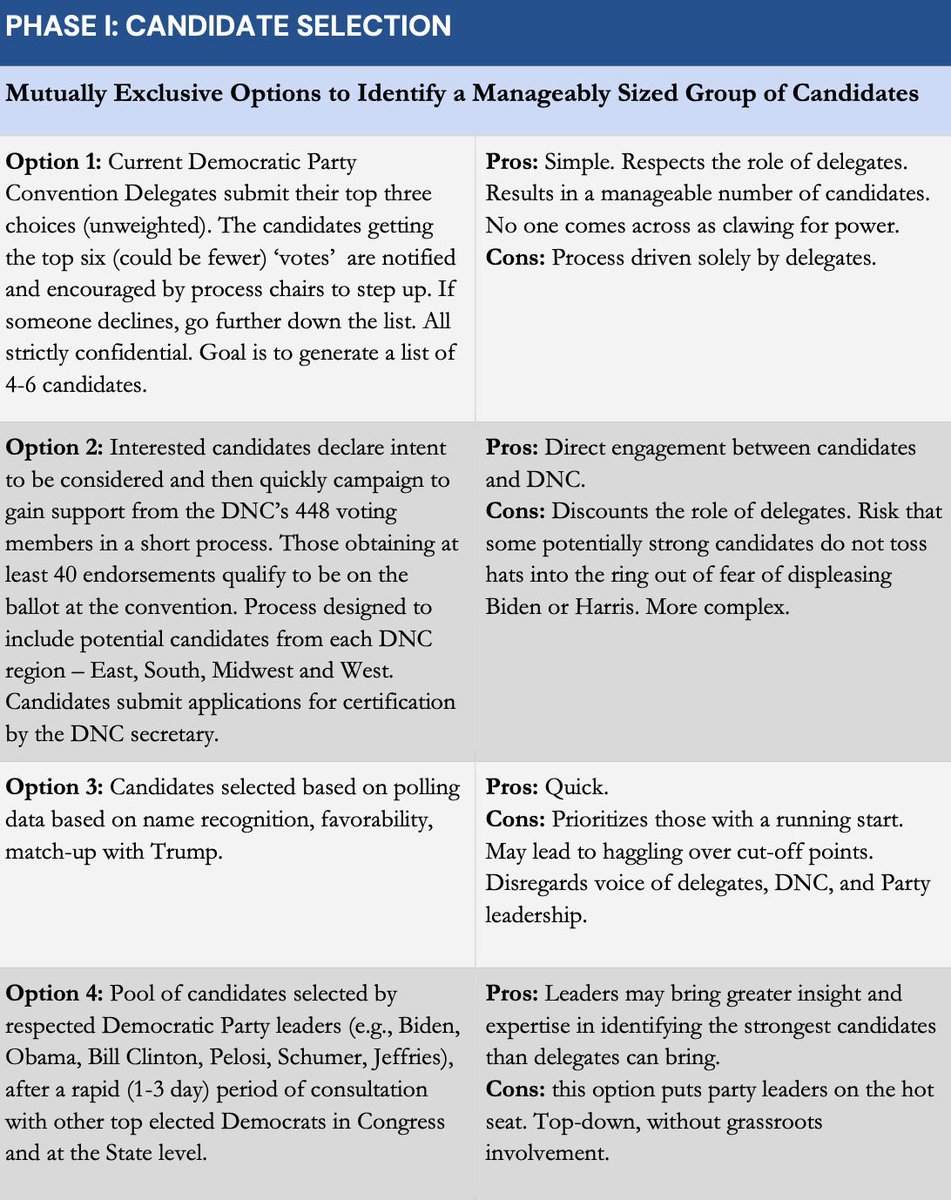

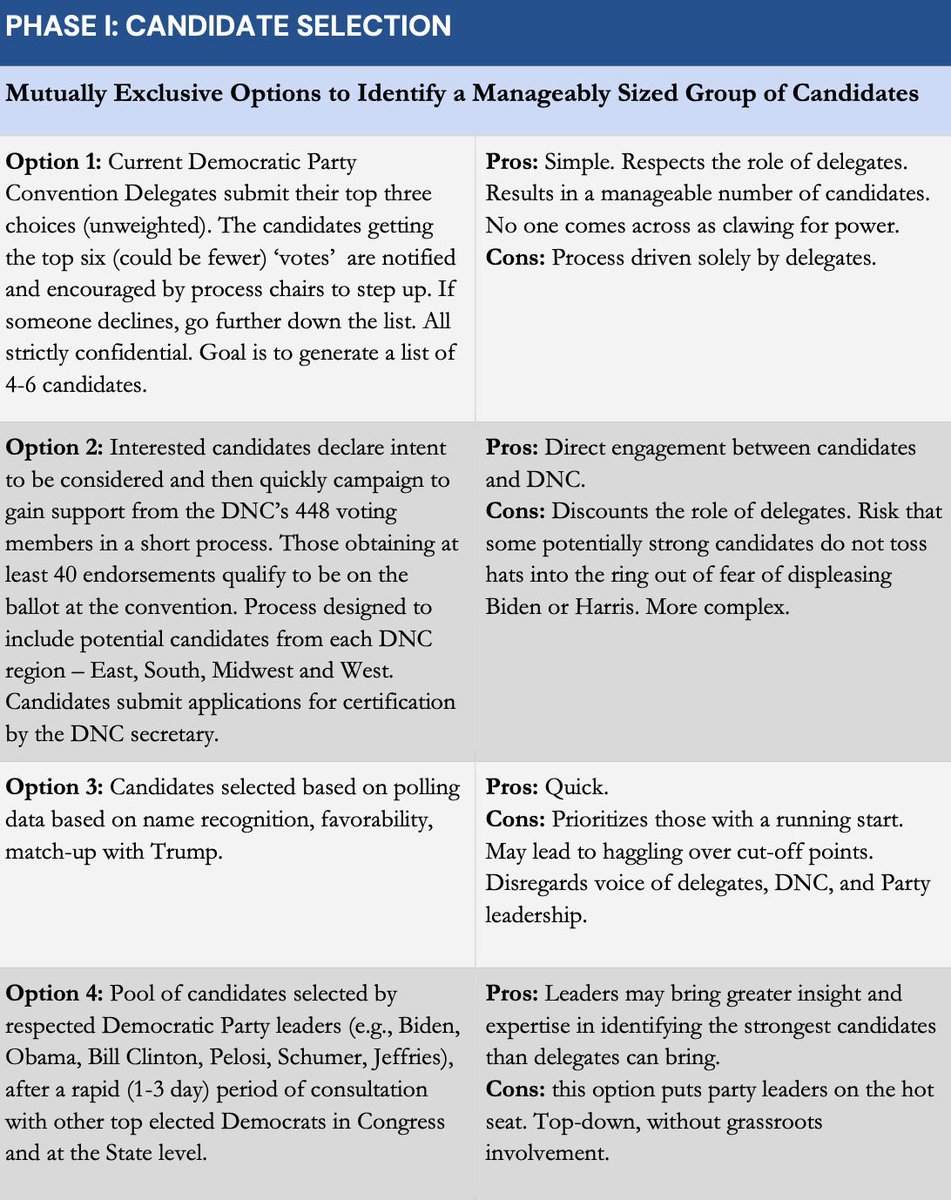

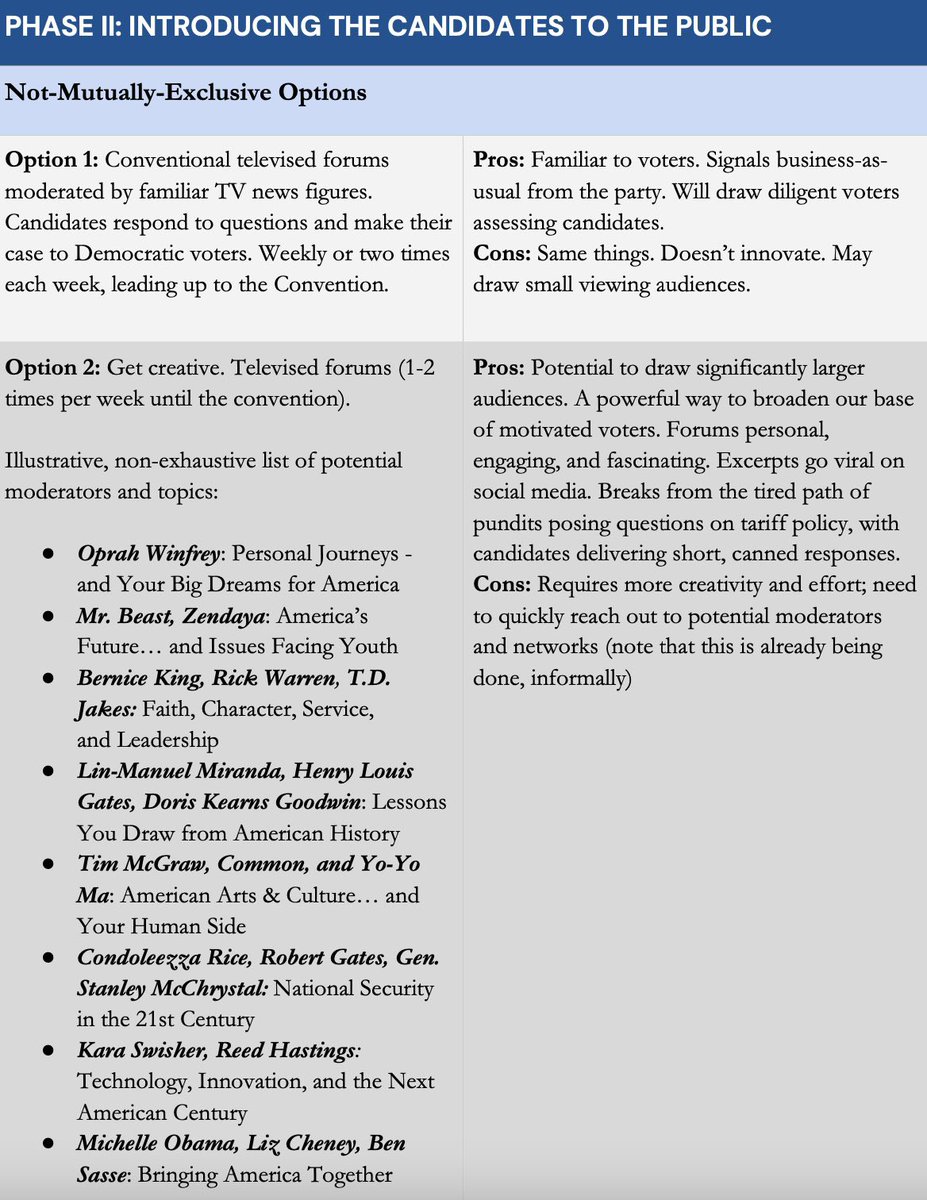

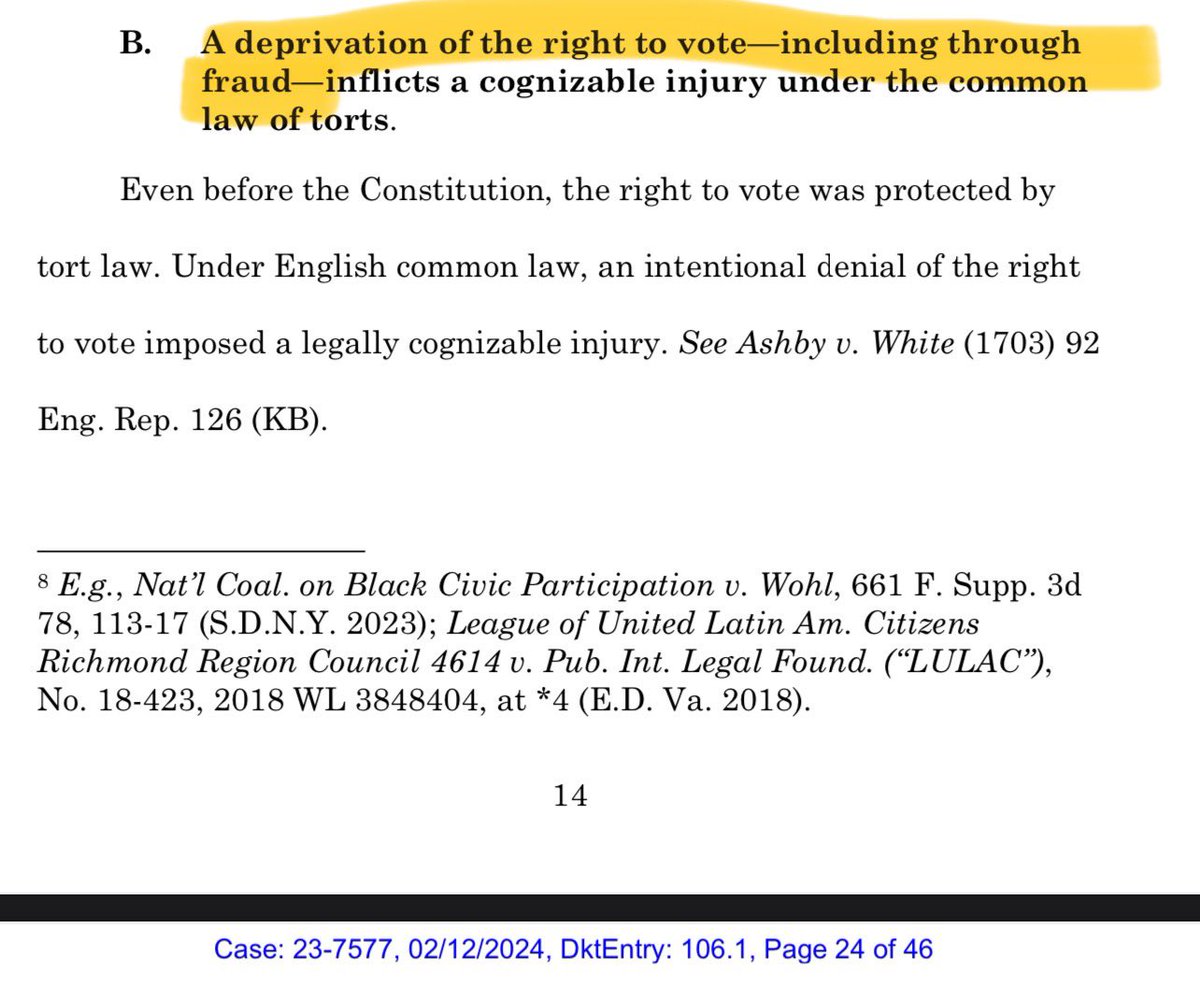

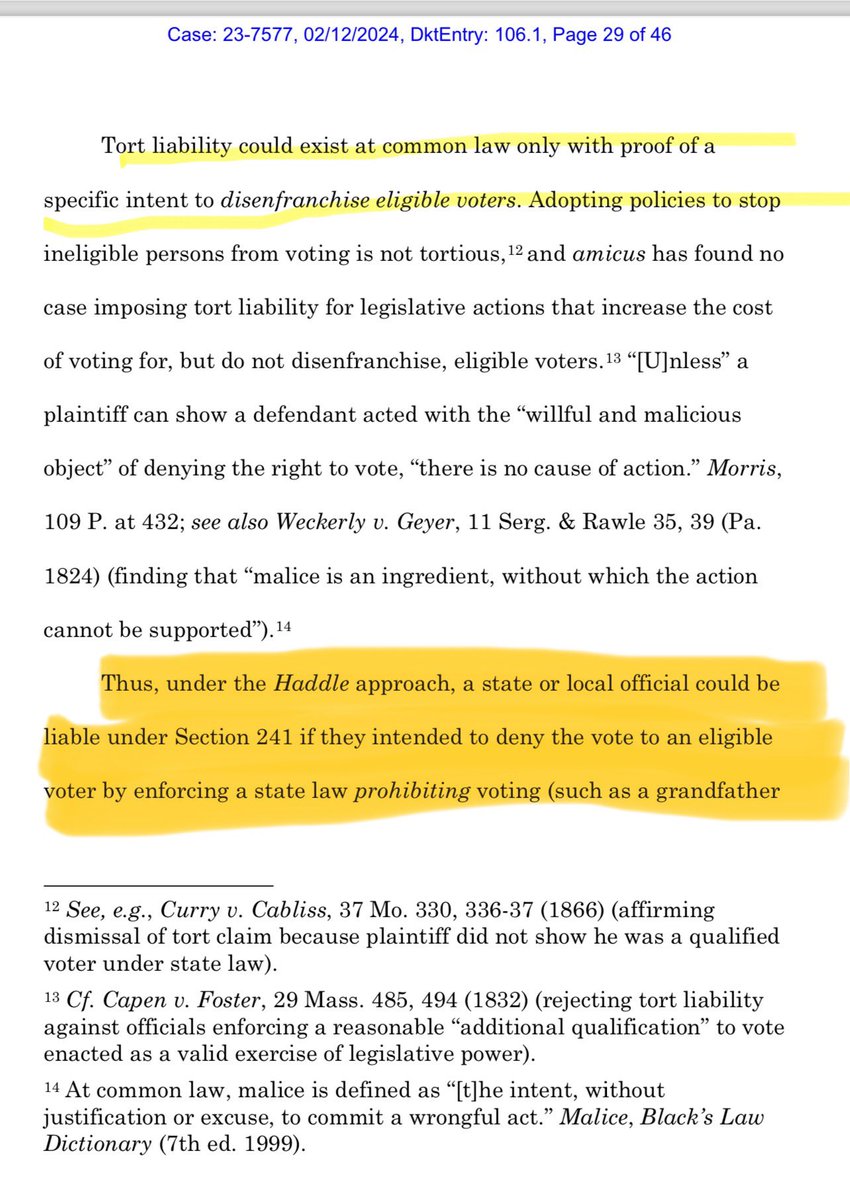

1. Campaign Influence and Legal Boundaries Theory

1. Campaign Influence and Legal Boundaries Theory