History is an unending dialogue between present and the past, that's why few pages of history give more insight than all the metaphysical volumes. (9)

18 subscribers

How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

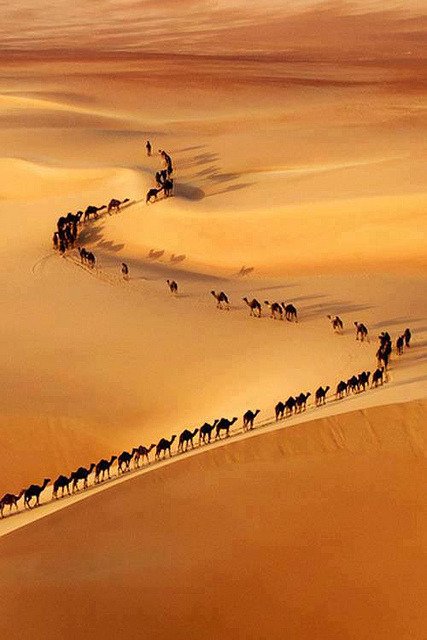

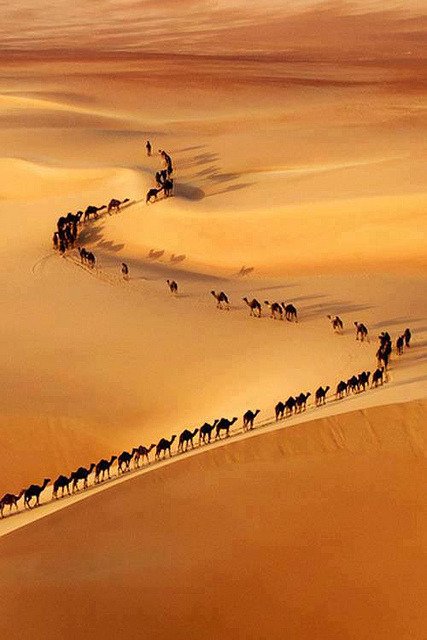

No one is sure when the camel entered history; some estimates say it was about-3000B.C. But in any case, funerary decorations in the pyramids show, the camel was known in Egypt before the Assyrian conquest of the seventh century B.C. (See Aramco World, May-June 1973), yet by that time the camel had already been established for 400 years in Syria and Palestine, a result of the Midianites' invasion in which they came "as grasshoppers.. .for both they and their camels were without number..." The Midianites vanished into history, but the camel remained and multiplied. Job, says the Bible, in one of its 31 references to camels, owned 6,000.

No one is sure when the camel entered history; some estimates say it was about-3000B.C. But in any case, funerary decorations in the pyramids show, the camel was known in Egypt before the Assyrian conquest of the seventh century B.C. (See Aramco World, May-June 1973), yet by that time the camel had already been established for 400 years in Syria and Palestine, a result of the Midianites' invasion in which they came "as grasshoppers.. .for both they and their camels were without number..." The Midianites vanished into history, but the camel remained and multiplied. Job, says the Bible, in one of its 31 references to camels, owned 6,000.

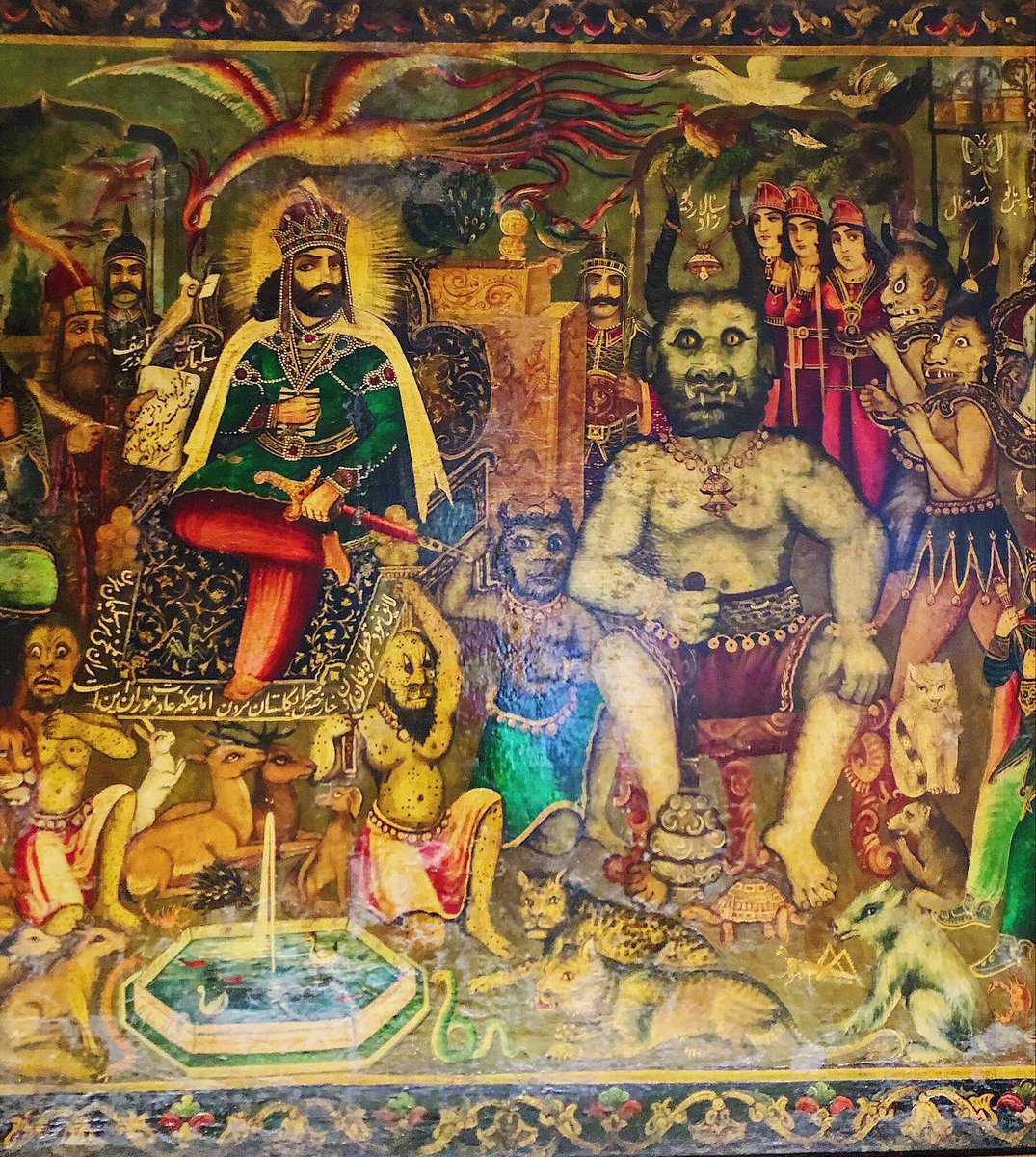

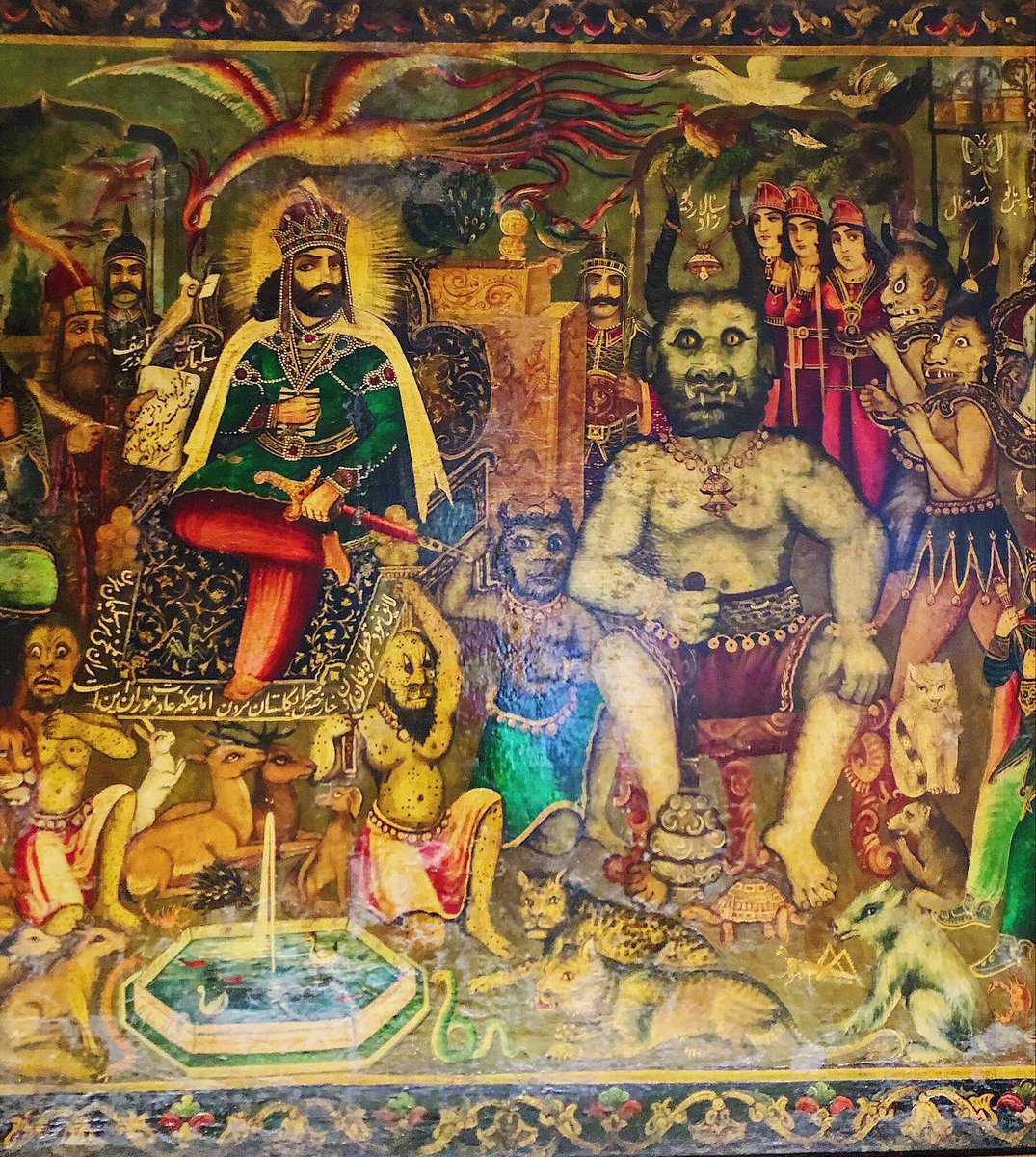

Over time, the painting has acquired a certain mystique, drawing attention not only for its subject matter but also for the artistic skill and talent of Heinrich Lossow. The detailed brushstrokes, the captivating use of color and light, and the intricate composition of the scene all contribute to the painting’s enduring appeal.

Over time, the painting has acquired a certain mystique, drawing attention not only for its subject matter but also for the artistic skill and talent of Heinrich Lossow. The detailed brushstrokes, the captivating use of color and light, and the intricate composition of the scene all contribute to the painting’s enduring appeal.

Just imagine a procession of disembodied heads and headless, hairy-legged, hoofed creatures shambling by. Doesn’t exactly make you want to go out and ask them to grant any wishes.

Just imagine a procession of disembodied heads and headless, hairy-legged, hoofed creatures shambling by. Doesn’t exactly make you want to go out and ask them to grant any wishes.

The number of slaves a person owned was a conspicuous measure of wealth. While the private home of an average person living in Rome might use five to twelve slaves, the urban residence of the elite might have up to five hundred performing tasks that only needed a small fraction of that total. A large agricultural estate might employ two or three thousand.

The number of slaves a person owned was a conspicuous measure of wealth. While the private home of an average person living in Rome might use five to twelve slaves, the urban residence of the elite might have up to five hundred performing tasks that only needed a small fraction of that total. A large agricultural estate might employ two or three thousand.

The 2011 edition of Catastrophobia titled Awakening the Planetary Mind: Beyond the Trauma of the Past to a New Era of Creativity has a whole new audience. Bored by old-paradigm Darwinian archeology that claims the human species has always advanced, young researchers hear me when I say we are a very damaged species because we were almost destroyed. Seeking what really happened to us so recently, they paint and pierce their bodies like hunter-gatherers at the end of the last ice age! Meanwhile, the recovery of our real story makes us realize people did survive radical climate changes, information that young people know they may need. Well, Göbekli Tepe goes right back to these great changes, so it is a gateway that can help us imagine who we were before we regressed. I think cosmic contact was severed 11,500 years ago. The recovery of the advanced astronomical knowledge of our ancestors is piercing the pain of human separation from the universe. Andrew Collins said to me in a recent email that he “probably didn’t fully understand the term catastrophobia until I started to piece together the motives behind the construction of Göbekli Tepe some 12,000 years ago. Then suddenly it all made sense! God, those people must have lived in fear, and without psychologists in those days, it was a matter that could only be rectified by shamans, which is exactly what I think happened.”

The 2011 edition of Catastrophobia titled Awakening the Planetary Mind: Beyond the Trauma of the Past to a New Era of Creativity has a whole new audience. Bored by old-paradigm Darwinian archeology that claims the human species has always advanced, young researchers hear me when I say we are a very damaged species because we were almost destroyed. Seeking what really happened to us so recently, they paint and pierce their bodies like hunter-gatherers at the end of the last ice age! Meanwhile, the recovery of our real story makes us realize people did survive radical climate changes, information that young people know they may need. Well, Göbekli Tepe goes right back to these great changes, so it is a gateway that can help us imagine who we were before we regressed. I think cosmic contact was severed 11,500 years ago. The recovery of the advanced astronomical knowledge of our ancestors is piercing the pain of human separation from the universe. Andrew Collins said to me in a recent email that he “probably didn’t fully understand the term catastrophobia until I started to piece together the motives behind the construction of Göbekli Tepe some 12,000 years ago. Then suddenly it all made sense! God, those people must have lived in fear, and without psychologists in those days, it was a matter that could only be rectified by shamans, which is exactly what I think happened.”

Sumerians lived in Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and Iran) between Tigris and Euphrates rivers from 4500-1750 BC. Despite being an ancient civilization, their reign was marked by a number of impressive technological advancements. For example, Sumerians invented plow, which played a huge role in helping their empire grow. They also developed cuneiform, one of earliest known systems of writing in human history. In addition, they came up with a method of keeping time, which modern people still use to this day.

Sumerians lived in Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and Iran) between Tigris and Euphrates rivers from 4500-1750 BC. Despite being an ancient civilization, their reign was marked by a number of impressive technological advancements. For example, Sumerians invented plow, which played a huge role in helping their empire grow. They also developed cuneiform, one of earliest known systems of writing in human history. In addition, they came up with a method of keeping time, which modern people still use to this day.

Over time, the painting has acquired a certain mystique, drawing attention not only for its subject matter but also for the artistic skill and talent of Heinrich Lossow. The detailed brushstrokes, the captivating use of color and light, and the intricate composition of the scene all contribute to the painting’s enduring appeal.

Over time, the painting has acquired a certain mystique, drawing attention not only for its subject matter but also for the artistic skill and talent of Heinrich Lossow. The detailed brushstrokes, the captivating use of color and light, and the intricate composition of the scene all contribute to the painting’s enduring appeal.

Hunting marine mammals such as seals called for real teamwork so that the Inuit could spot them, follow them, kill them and cut them up. In winter, dogs would sniff out the mammals’ breathing holes in the ice pack and then the hunters would lie in wait, and as soon as a seal came up for air it was harpooned. In spring, mammals could be killed while they sunned themselves on the rocks or ice, and in summer they were hunted at sea using kayaks.

Hunting marine mammals such as seals called for real teamwork so that the Inuit could spot them, follow them, kill them and cut them up. In winter, dogs would sniff out the mammals’ breathing holes in the ice pack and then the hunters would lie in wait, and as soon as a seal came up for air it was harpooned. In spring, mammals could be killed while they sunned themselves on the rocks or ice, and in summer they were hunted at sea using kayaks.

However while the Teutonic Order was given relative autonomy in the functioning of its troops in the region, Hungarian king prohibited knights from erecting stone-based fortifications – probably because he didn’t want the order to be a militarily independent faction with strong political influence in the area. But the Teutonic Knights broke their agreement and started constructing stone-based castles, and at the same successfully repelled various Kipchak raids.

However while the Teutonic Order was given relative autonomy in the functioning of its troops in the region, Hungarian king prohibited knights from erecting stone-based fortifications – probably because he didn’t want the order to be a militarily independent faction with strong political influence in the area. But the Teutonic Knights broke their agreement and started constructing stone-based castles, and at the same successfully repelled various Kipchak raids.

Upon seizing power, Philip’s immediate political concerns were the Illyrians. Having killed his predecessor in battle, the Illyrians posed a unique threat as they had been emboldened by their success and might inspire others to revolt against Macedonian power. Philip marched to meet the Illyrians in the Erigon Valley in 358 BC, where he decisively defeated them and slew their king on the field.

Upon seizing power, Philip’s immediate political concerns were the Illyrians. Having killed his predecessor in battle, the Illyrians posed a unique threat as they had been emboldened by their success and might inspire others to revolt against Macedonian power. Philip marched to meet the Illyrians in the Erigon Valley in 358 BC, where he decisively defeated them and slew their king on the field.

The frescos from the Tomb of the Bulls (Tombe dei Tori) in Tarquinia are characterised by fertility symbols, although the meaning of some of the symbolism is not entirely clear. The panel on the left depicts a heterosexual scene involving two couples, whereas the scene on the right depicts a homosexual scene. This has been variously interpreted. It is noted that the bull on the right has an aggressive pose, whereas the bull on the left is completed passive, which has been interpreted by some authors as a disapproval of homosexuality. Note also that the bulls have human faces, possibly indicating some mythological context.

The frescos from the Tomb of the Bulls (Tombe dei Tori) in Tarquinia are characterised by fertility symbols, although the meaning of some of the symbolism is not entirely clear. The panel on the left depicts a heterosexual scene involving two couples, whereas the scene on the right depicts a homosexual scene. This has been variously interpreted. It is noted that the bull on the right has an aggressive pose, whereas the bull on the left is completed passive, which has been interpreted by some authors as a disapproval of homosexuality. Note also that the bulls have human faces, possibly indicating some mythological context.

At first it was thought that the ‘bull-cult’ had been confined to the royal precincts at Knossos; but examination of the palaces at Phaistos and Malia, the ‘summer palace’ at Hagia Triada and other important sites at Zakro, Armenoi and Pseira, has provided evidence that the phenomenon was fairly widespread throughout the island.

At first it was thought that the ‘bull-cult’ had been confined to the royal precincts at Knossos; but examination of the palaces at Phaistos and Malia, the ‘summer palace’ at Hagia Triada and other important sites at Zakro, Armenoi and Pseira, has provided evidence that the phenomenon was fairly widespread throughout the island.

The presence of infectious disease in the Neolithic can be examined in several ways. The most common is through the archaeological record. For decades, the presence of mass graves and skeletal markers of disease after excavation were the only available indicators of pathogens from thousands of years ago. As a result, this type of analysis has become very robust. The combination of various skeletal deformities and lesions can distinguish between similar diseases; tuberculosis and syphilis, for example, can both cause bone lesions, but syphilis does so specifically on the face and may affect the long bones like the tibia in unique ways. Unfortunately, these methods limit paleomicrobiology to the effects of the microbes and not organisms themselves. As a result, skeletal paleopathology only identifies microbes that cause diseases that affect bone and have cases severe enough to be visible on skeleton. Diseases caused by Treponema like syphilis and yaws, for example, only start permanently affecting bone when they reach the tertiary stage. This stage only occurs in one of every three untreated cases, suggesting that diseases significantly affecting quality of life and population demographics may be seriously underrepresented.

The presence of infectious disease in the Neolithic can be examined in several ways. The most common is through the archaeological record. For decades, the presence of mass graves and skeletal markers of disease after excavation were the only available indicators of pathogens from thousands of years ago. As a result, this type of analysis has become very robust. The combination of various skeletal deformities and lesions can distinguish between similar diseases; tuberculosis and syphilis, for example, can both cause bone lesions, but syphilis does so specifically on the face and may affect the long bones like the tibia in unique ways. Unfortunately, these methods limit paleomicrobiology to the effects of the microbes and not organisms themselves. As a result, skeletal paleopathology only identifies microbes that cause diseases that affect bone and have cases severe enough to be visible on skeleton. Diseases caused by Treponema like syphilis and yaws, for example, only start permanently affecting bone when they reach the tertiary stage. This stage only occurs in one of every three untreated cases, suggesting that diseases significantly affecting quality of life and population demographics may be seriously underrepresented.

• Temple of Artemis at Ephesus :

• Temple of Artemis at Ephesus :

The Soma was a landmark of the city and its fame drew visitors from far and wide. That only makes its disappearance more peculiar. The last recorded visit to the tomb was in 215 CE when the Roman emperor Caracalla visited during his time in Egypt. Caracalla ordered some of the burial goods to be removed but supposedly added some of his own gifts to the burial as compensation. After this, the tomb and Alexander’s body are only referenced off-handedly.

The Soma was a landmark of the city and its fame drew visitors from far and wide. That only makes its disappearance more peculiar. The last recorded visit to the tomb was in 215 CE when the Roman emperor Caracalla visited during his time in Egypt. Caracalla ordered some of the burial goods to be removed but supposedly added some of his own gifts to the burial as compensation. After this, the tomb and Alexander’s body are only referenced off-handedly.

Ancient Urban Landscapes of the Amazon – A Deeper Dive into the Discoveries

Ancient Urban Landscapes of the Amazon – A Deeper Dive into the Discoveries

Tell me about medieval Islamic civilization. Wasn’t there a flowering in the 9th and 10th centuries?

Tell me about medieval Islamic civilization. Wasn’t there a flowering in the 9th and 10th centuries?

After conquering a place, Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire were good about inducting talent and new ideas into his own lexicon of success. A wonderful example of this is a man Chu-Tsai, a Giant by any conventional standards (standing 6’8”) Governor of North China who worked for Genghis Khan as a chancery (tax and laws book keeper) despite having previously worked for one of Genghis’ rivals, the Jin Emperor. He (Chu-Tsai) would spend many years attempting to reign in Kublai’s uncle, Ogadai’s dreadful drinking and spending habits, recommending a more reserved life instead. Going as far as suggesting, that Ogadai should nurture and tax the poor, rather than razing them along with the crops to make room for horse pasture. Implemented in 1230, this method of taxation produced 10,000 silver ingots ad likely spared many lives, a revolutionary idea for the time. Genghis is succeeded by Ogadai “whose kingdom was won on horseback, could not be governed there” said Chu-Tsai.

After conquering a place, Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire were good about inducting talent and new ideas into his own lexicon of success. A wonderful example of this is a man Chu-Tsai, a Giant by any conventional standards (standing 6’8”) Governor of North China who worked for Genghis Khan as a chancery (tax and laws book keeper) despite having previously worked for one of Genghis’ rivals, the Jin Emperor. He (Chu-Tsai) would spend many years attempting to reign in Kublai’s uncle, Ogadai’s dreadful drinking and spending habits, recommending a more reserved life instead. Going as far as suggesting, that Ogadai should nurture and tax the poor, rather than razing them along with the crops to make room for horse pasture. Implemented in 1230, this method of taxation produced 10,000 silver ingots ad likely spared many lives, a revolutionary idea for the time. Genghis is succeeded by Ogadai “whose kingdom was won on horseback, could not be governed there” said Chu-Tsai.

During that winter the sultan gathered the resources for war against Acre. Giant trees were cut down in the mountains of the Lebanon and laboriously hauled to Damascus to be fashioned into catapults. Siege miners were summoned from Aleppo. Troop detachments were requisitioned from all the vassal princes in Palestine and Syria. Preaching in the mosques in the name of jihad fired up the ordinary people to volunteer for the cause. The Christians also made increasingly desperate calls to Europe for a new crusade to save the city. The pope issued a general encyclical exhorting people to take the crusade but the response was limited. The appetite for crusading ventures by the kings and great nobles of Europe was dying. In the end only 3,000 men made it. Few of them were professional soldiers.

During that winter the sultan gathered the resources for war against Acre. Giant trees were cut down in the mountains of the Lebanon and laboriously hauled to Damascus to be fashioned into catapults. Siege miners were summoned from Aleppo. Troop detachments were requisitioned from all the vassal princes in Palestine and Syria. Preaching in the mosques in the name of jihad fired up the ordinary people to volunteer for the cause. The Christians also made increasingly desperate calls to Europe for a new crusade to save the city. The pope issued a general encyclical exhorting people to take the crusade but the response was limited. The appetite for crusading ventures by the kings and great nobles of Europe was dying. In the end only 3,000 men made it. Few of them were professional soldiers.