The great horror of this age is that we know so much, but are still as incapable as ever. How do we stop this madness? What purpose does it serve?

https://twitter.com/jamesdenselow/status/1058727207978369024

Because I don’t have any better ideas on how to stop this horror, I’d like to retain your attention with an account of another famine, which took place just 75 years ago in Amsterdam and other Dutch cities during the Hunger Winter of 1944-’45.

At the time, my grandparents were running a drugstore in Amsterdam West, which meant they had it pretty easy compared to most other people, because they had plenty to trade in exchange for food, when their money proved to be inedible.

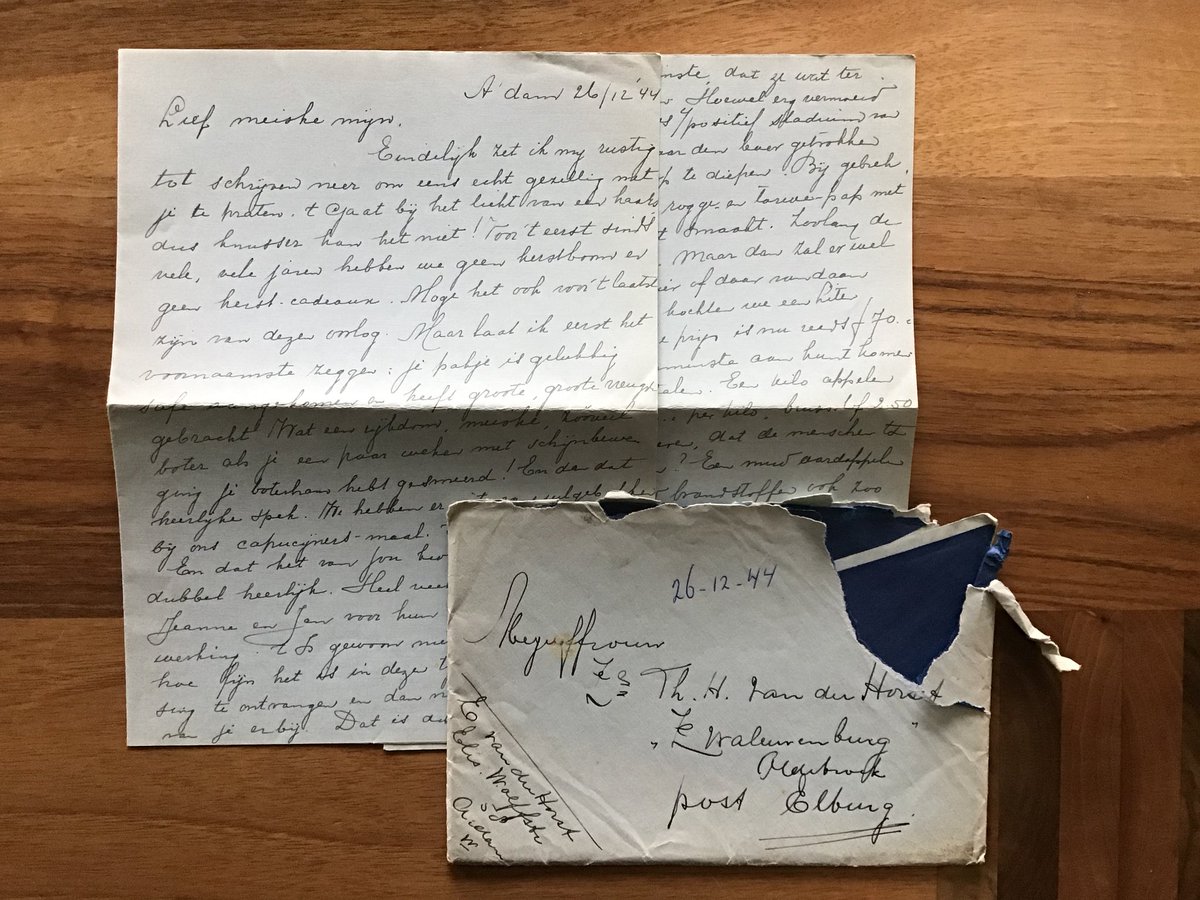

My grandmother wrote letters to my mother, who was working as a nurse out in the countryside, where food was more plentiful, leading to a constant stream of hungry people from the cities, walking long distances to beg farmers for food to bring home to their starving families.

The tone of my grandmother’s letters changes gradually as the situation becomes more desperate and macabre. I’d like to share some excerpts from her letters here, perhaps as a daily reminder that people are starving to death, and in 75 years’ time it may be our grandchildren.

Friday 16 June 1944 | “Listen love, please don’t forget the groceries and keep finding ways to send us a little extra. You know what we need. Your mumsy is still feeling weak and easily tired. If you can’t get meat, it would be good to get butter, cheese, eggs etc. Can you help?"

23 June 1944 | “Things have calmed down in the shop, but life is incredibly expensive. Vegetables are hard to come by or much too expensive, and everything else is rationed. We received the package you sent. Thanks ever so much.”

23 June 1944 | “We received word that 31 locomotive were shot to pieces the day before yesterday. If they keep that up, we’ll have none left soon. I’d really like to visit Uncle Theo and Aunt Marie in Hilversum, but the train trip is a nightmare...” [Amsterdam-Hilversum = 30+km]

“...Not because of the shooting, but because it’s so dreadfully busy and you almost suffocate if you’re sitting down, that’s if you’re lucky enough to get on board! Sadly, I don’t have a bicycle at my disposal. And so we wait for better days, if they are to be granted.”

*** I'll try to update this thread daily at noon CET. Meanwhile, let's see if we can convince @MinPres and other European leaders to increase the pressure to end the attacks on Yemen and allow relief aid to be brought to those who are being starved to death. ***

23 June 1944 | “Vinolia have stopped supplying shaving cream, because the quality has gotten so bad they don’t want their brand on it! And so we’re losing one thing after another. Well, I suppose things need to get worse before they get better, as people always say.”

19 July 1944 | “Today we got a tip for a place to stay in Putten. People we know are staying there and the conditions look good; pre-war food situation and 6 guilders per person per day. It sounds like a great option. Not terribly far away and the surroundings are magnificent.”

8 October 1944 | “Things are getting out of hand here. No electricity since this morning. Only the three biggest hospitals have electricity. All the others have to work in darkness and get by as best they can. The shops are open from 10 till 4...”

“...Apparently, there’s only enough gas left for another week. After that, we’ll probably have to get food from the central kitchen. Will you be joining us for dinner? The war seems to have ground to a halt, we hear. I wonder how long it will stay that way.”

8 October 1944 | Yesterday was Saturday, the last day the lights were on, so everyone was working like mad, vacuuming, washing, ironing etc. etc. etc. All of which meant that the electricity had been used up by 8 ‘o clock, and so the lights slowly faded and then went out.

“...I’m going to sign off now. I want to use the warm water to wash my hair. Dear sister, congratulations again on your 21st birthday! Wishing the very best and a lovely day. Hope to see you soon. Bye, honey. A big kiss from your sister.” [My mother turned 21 on 11 October 1944.]

5 November 1944 | “Your letter finally arrived on 31 October, eleven days after it was dated! We were glad to hear you had a festive birthday dinner, even though it was delayed. Better late than not at all.”

[...] “You know what’s a real shame? Our telephone has been cut off, so you won’t be able to call us anymore. But your sister says she’ll write and tell you how you can contact her via the pharmacy if you have anything special to report or just to tell us how you are.”

[...] “There has been terrible fighting. We hear that Apeldoorn was heavily bombed. Evacuees keep flooding into Holland. Lots of the wounded are being brought here by river barge. As many as 800, we hear. After dark, the Red Cross vehicles ferry the wounded to hospitals.”

5 November 1944 | “The situation in A’dam is far from bright. No gas, no electricity, no butter, fat or margarine or other victuals available with food stamps, except cheese, which they fortunately did have until now. We haven’t had meat for weeks, except on stamps for the sick.”

[...] “And the black market has all but dried up. They’re demanding exorbitant prices for all sorts of combustible oil, anthracite and potatoes. This week they were charging 30 guilders/litre for petroleum, 90-100 guilders/70kg for potatoes, 100-125 guilders/70kg for anthracite.”

[...] “They’re chopping down trees like it’s a national pastime. They've razed the entire Amsterdam wood and all the trees along the Zuidelijke Wandelweg. They’ve even started stealing the wooden blocks between the tram rails and the wooden paving under the Rijksmuseum!”

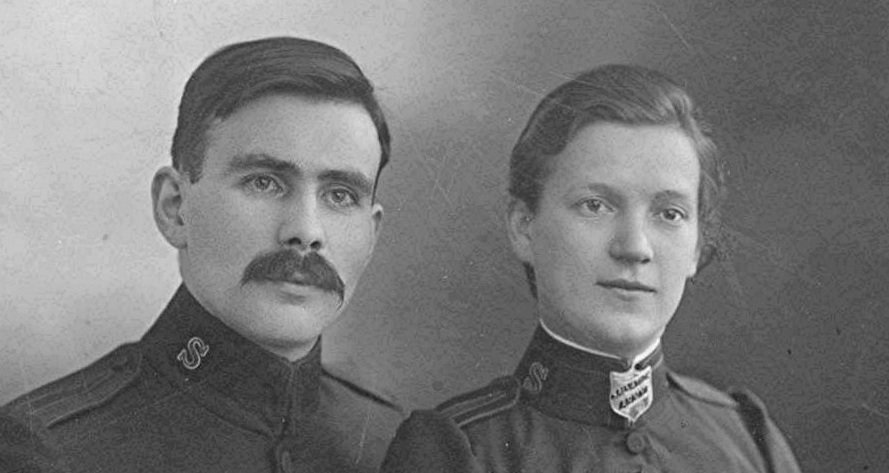

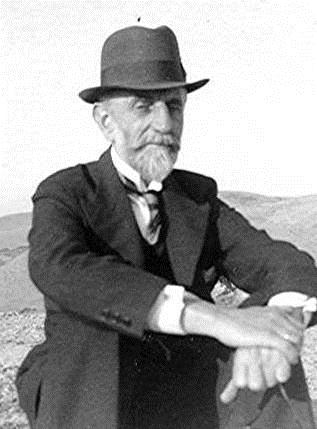

Your famine reporter, Charlotte van der Horst-van Charldorp, is on the right. Before opening their drugstore, my grandparents worked for the Salvation Army.

5 November 1944 | "Lots of families have only been issued fuel for 1 month. We've received the full 4-month ration, but that also has its dangers, especially if you don’t get your meals from the central kitchen, like us, which means cooking everything on the stove in the lounge."

"[...] “The central kitchen issues a ½ litre of food per person. Something like: 3 x mash & veg, 2 x porridge and 2 x soup. On Sundays there’s porridge too, I think. Everyone has a designated hour to fetch their food..."

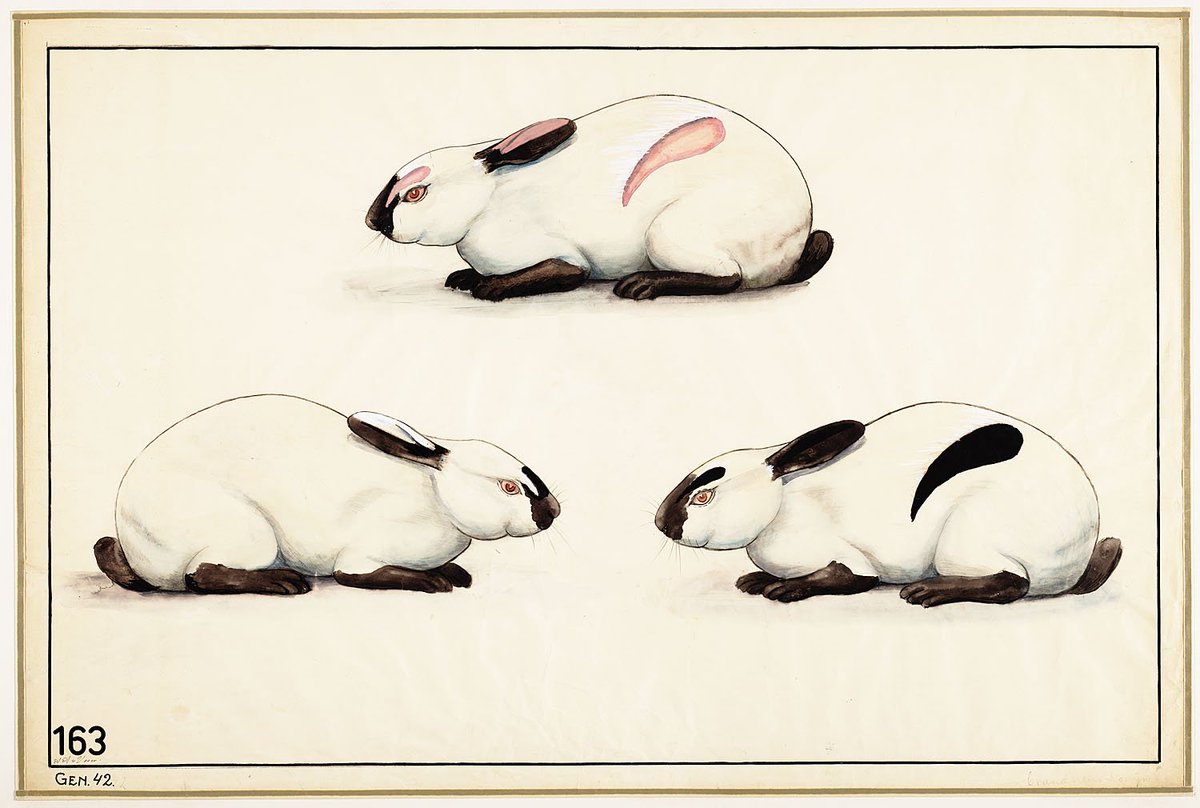

“That means you have to heat it up and do a bit of extra cooking, because it usually isn’t enough. So we’ve decided to do our own cooking, because it means we can set our own menu. Coming Wednesday 8 Nov. we have rabbit with apple sauce on the menu!” (My grandfather's birthday.)

“It just won’t be the same without our Benjamin. You'll be in our hearts and the knowledge that you're safe and have enough to eat will be of comfort to us. We live day by day and entrust ourselves to our loyal Guide, who has the power to offer care beyond prayer and thought.”

22 November 1944 | “Dearest fille cadette. Thanks a million for the ration stamps you sent! They vanished like a drop of water on a hotplate, and I hope we’ll keep seeing that figure of speech in literal form in the months ahead, because fuel is becoming a major problem.”

“[...] All the stamps were still valid, except the full-cream milk, so I’ve sent those back to you. I need to go for a run-around soon as possible to cash them in, or better yet ‘food them in’, because food is more valuable than gold nowadays and almost as difficult to obtain.”

“[...] The situation is going to get completely out of hand in the foreseeable future. From next week, we’ll be down to one loaf of bread per person per week, apparently. For the past fortnight, we’ve had two loaves per person per week. Everyone’s nerves are frayed.”

If you're ever at the Paradiso music centre near Leidseplein, look across the tram rails to the entrance of the Barlaeus Gymnasium, that's where the above photo was taken.

22 November 1944 | “I really wish we could get some powdered milk, otherwise I don’t know what we'll feed the cat. We’re hoping to get some full-cream powder via one of Katrien’s contacts. Butter, margarine and fat are hard to come these days.”

“[...] This week we’ll be getting a half litre of rape-seed oil, which will have to last until 31 December, we’ve been told. Cheers! Potatoes are beyond our means on the black market (80-100 guilders per 70kgs). And there are no beans, etcetera, etcetera, etcetera.”

“[...] The fat ration we were supposed to get for this fortnight hasn’t even been delivered to the shopkeepers. Only the cheese stamps are being paid out with half-cream cheese. It’s getting to the point where we don’t know what we miss most.”

“[...] We’ve managed to get by pretty well until now, but the threat of hunger is now lurking just outside our tents. No coffee milk for Char yesterday, no milk for the cat, and no porridge this morning. And so we all ate more bread and exceeded our limit.”

22 November 1944 | “Today we’re trading in the skimmed-milk stamp you sent us. Fortunately, we also got some full-cream milk. 1 litre costs 2.40 guilders, if you can get it! Anneke sent us a package from Friesland (the linen she’d borrowed) in which she’d hidden 1 kg of butter!”

“[...] We were overjoyed! She says she’ll try to get more, and potatoes, as soon as she’s out of the quarantine ward where she’s working as a nurse. Apparently, the post are accepting packages again. But nothing heavier than 2 kg. Maybe you can help us hungry folk here in A'dam.”

“[...] Maybe you can phone around to check the options. Anything is welcome, even powdered milk. And don’t forget: the sooner the better. Maybe you could even hide a chunk of bacon in there. Everything out of Friesland is arriving intact, although it’s taking longer to get here.”

22 November 1944 | “You’re probably thinking: what a fun letter, full of needs and wishes! But don’t forget things are never as bad as they seem. We’re taking vitamin tablets and a couple of spoonfuls of Biomals every day! If need be, we’ll even switch to cod-liver oil! Brrr!”

[People with a doctor’s prescription are issued Biomals with priority, so that this fortifying elixir is easily available to new mothers and mothers-to-be, the frail, the ill and children. But...don’t forget to return you empty container! BIOMALS The power of sprouting corn.]

“[...] In the evenings, we sit around an oil lamp and our throats are always dry, because there’s not tea to be had. And of course there’s no sugar either. 125 grams every fortnight, and then you get brown sugar. Even I have learned to eat porridge without sugar.”

This is from the Diary of Anne Frank, in case that wasn’t clear.

22 November 1944 | “We could perform several plays featuring the acrobatics needed to prepare our afternoon meal. Papa and Charry sequester themselves in the garden shed with our reserve stove; a rusty, corrugated-iron barrel, through which round rods have been driven.”

“[...] These rods are supposed to form the grill, but they were clearly conceived by a man, because they’re so far apart that anything that wasn’t king-sized fell into the fire. So we are using the zinc filter plate out of our old washing machine as a grill on top of the rods.”

“[...] But it’s a real adventure to poke up the fire through the holes in the grill. And whenever you want to add a piece of cardboard to the fire, you first have to lift up the pan and then the washing-machine grill, which is why it is strictly a two-man stove!”

“[...] The neighbours lament this innovation, because of the crude smoke which, with apparent disregard for any law or rule, favours one group of neighbours and then the next. ‘What a to-do, your smoke!’ one lady moaned. To which Papa replied, unflappable: ‘It’s war down here!’”

22 November 1944 | “Thank goodness they manage get dinner done each time. I can see Papa and Char emerging triumphantly from the realm of shadows with our afternoon meal or rather: our evening dinner, because darkness is already falling all around. What has become of the world?"

“[...] What never-racking times we live in. No wonder the psychiatric hospitals are full. If we don’t watch out, 9/10ths of humanity will be candidates for commitment. Everyone’s nerves are frayed. Even the most peaceful couples have become belligerent.”

“[...] We’re expecting a major roundup of men in the 17-40 age group, which means an extra dose of terror and anxiety for thousands of families. And the war? Metz has fallen, as well as Belvoirt, and there are rumours that the Allies have crossed the Rhine at Aachen.”

10 December 1944 | “Regrettably, we spend the days here asking ourselves: what shall we eat and drink? Materialism is running riot in our existence, affecting everything it touches and consorts with. Happy is he who is not entirely absorbed, because it ravages the soul.”

“[...] May the mercy of the Lord touch our souls and raise them above ‘the shattering cry and muddy ooze’, so that we may be what we were born to be: a city upon a hill, radiating light in the darkness of the night. Ever do we — do I — fall short in this respect!”

“[...] Dear child, when will we see one another again? All this is taking so long and there are so few glimmers of hope and silver linings. Hunger lurks at our doors.”

please don't forget

the groceries, love

keep finding ways

to send a little extra

meat might be nice

but butter, cheese

and eggs will do

you know our needs

please don't forget

keep finding ways

the groceries, love

mumsy's feeling weak

and easily tired

please don't forget

the groceries, love

keep finding ways

to send a little extra

meat might be nice

but butter, cheese

and eggs will do

you know our needs

please don't forget

keep finding ways

the groceries, love

mumsy's feeling weak

and easily tired

please don't forget

things have calmed

down in the shop

but life is so expensive

vegetables are hard

to come by and

incredibly expensive

and everything else

is rationed and

outrageously expensive

we got the package

thanks ever so much

I really hope it wasn't

terribly expensive

down in the shop

but life is so expensive

vegetables are hard

to come by and

incredibly expensive

and everything else

is rationed and

outrageously expensive

we got the package

thanks ever so much

I really hope it wasn't

terribly expensive

'Zeg Theke, denk je nog aan middelen en wegen om ons van wat extra’s te voorzien. Je weet wat we nodig hebben. Je moedertje voelt zich nog steeds slap en erg gauw vermoeid, maar waar ‘k geen vleesch mag eten zal ’t goed zijn boter, kaas, eieren enz. te krijgen.' #Brieven44

the train trip is a nightmare

not because of the shooting

but it’s so dreadfully busy

you almost suffocate

when you’re sitting down

that’s if you’re lucky

enough to get on board

and so we wait for better days

wishing for our bikes back

not because of the shooting

but it’s so dreadfully busy

you almost suffocate

when you’re sitting down

that’s if you’re lucky

enough to get on board

and so we wait for better days

wishing for our bikes back

11 December 1944 | Papa writes | “I’m writing this as I wait for the water to boil. Things are hectic in the store and with all the other chores: keeping the stove alight, chopping up anything that will burn, making sure we have enough food on the table and goods in the store.”

“[...] But we keep cheerfully buying whatever we can lay our hands on and we really haven’t had cause to complain, although our butter and fat situation is getting precarious. Is there no way of sending something to Amsterdam by boat via Elburg, Nunspeet or Harderwijk?"

“[...] We could also really use some rye, potatoes, apples etc. Anneke sent us 15 kilos of potatoes last week using the Lemmer Boat. We swapped 9 kilos of potatoes for a ½ pound of sugar. This week we have 600 grams of bread per person, that’s ¾ of a loaf.”

“We see this great city teetering on the brink of famine. Fortunately, we still have some cod-liver oil and vitamin preparations for ourselves and for those close to us. And now the page is almost full. Bye, dear child. Until next we meet, God willing.”

18 December 1944 | Sister Charry writes: “How are things, girly? Still keeping your spirits up? It’s going to be really strange not having you home for the festive season. Hopefully you’ll be in good company there. We can’t even get a Christmas tree here!”

“[...] At our Salvation Army meetings we have candlelight + blazing stoves, all of which is arranged by the attendees; one brings a candle, another a tea light, another a block of wood or a shovelful of coal. Very festive indeed, which is lovely because it has been freezing!"

[...] “We are now getting, per head: 1 kg of potatoes + 1000 gr of bread (= 1½ loaf) + 1 ounce of cheese. That’s all! Isn’t it awful? Things really are desperate. Fortunately, we get a buck full of food from the Central Kitchen every day, which we share with the Palstra Family.”

[...] “Rudi Hordijk brings us the food from Rapenburg, where they get whatever leftovers are available. Papa then adds all sorts of condiments, which actually makes the food quite tasty! I’m not sure if we’re allowed to share this with the world, so keep it to yourself!”

18 December 1944 | “Do you have any more funny stories to tell? There’s not a lot happening here. Everyone is down and touchy. If you don’t watch your words, you get into arguments before you know it, even with strangers who come into pharmacy for something or other. Bizarre!”

“[...] Well, girly, I’m going to end off. You probably won’t get this letter on time, but all the same we wish you a blessed Christmas, a joyous year end and a happy New Year! Here’s hoping 1945 will bring what we all desire most: Peace! Not just for us, but for the whole world.”

26 December 1944 | “Finally I’ve found time to sit down and have a lovely chat with you. I’m writing by candlelight. Could it get any cosier? For the first time in many, many years we had no Christmas tree and no Christmas gifts. Hopefully, it will be the last time in this war.”

“[...] But let me start with the most important news: your parcel arrived safely and brought us great, great joy. Such bountiful treats, girly, sóóó much butter, especially if you’ve spent the past weeks spreading sweet-nothing on your slices!”

“[...] And then that lovely bacon! We fried some down and had it with our field peas. It was delicious. The fact that it came from you, made it all the more tasty. Thank you so much! It really is hard to express what it’s like to receive a surprise like this in these dark days.”

“[...] The fact that the parcel also contained a letter from you, made it a double delight!”

26 December 1944 | “How’s the heating round your way? You must also be struggling too, dearie. If I knew you could find a place for us, where it’s nice ‘n’ warm and where we really wouldn’t be in anyone’s way, who knows we might come knocking, if things get any worse here.”

“[...] Papa will hear nothing of it. He’s afraid they’ll plunder the whole place, including the furniture, and tear the house down. I certainly wouldn’t put it past them. There really have been lots of burglaries and baker’s carts robbed and shops plundered."

"But if people have nothing in reserve, it’s worse than awful.”

'Eindelijk rust om eens echt gezellig met je te praten. ’t Gaat bij het licht van een kaars, dus knusser kan het niet! Voor ’t eerst sinds vele, vele jaren hebben we geen kerstboom en geen kerst-cadeaux. Moge het ook voor ’t laatst zijn van dezen oorlog.'

'Maar laat ik eerst het voornaamste zeggen: je pakje is gelukkig safe aangekomen en heeft grote, grote vreugde gebracht. Wat een rijkdom, meiske, zóóveel boter als je een paar weken met schijnbeweging je boterham hebt gesmeerd!'

'En dan dat heerlijke spek. We hebben er iets van uitgebakken bij ons capucijners-maal. ’t Was delicious. En dat het van jouw kwam, maakte het dubbel heerlijk. ’t Is gewoon niet uit te drukken, hoe fijn het is in dezen tijd zulk een verrassing te ontvangen.'

26 December 1944 | “Last week, Papa stood in the misty cold for three hours to exchange a couple of coupons for fat, which had been issued in late October or early November. Quite by chance, he was the last to get anything.”

“When he got to the shop at 9 o’clock there were already 400 people waiting. Another 300 joined the queue behind him, but they got nothing. Officially, they’re still issuing coupons, but the truth is that lots of people stand waiting in the cold for hours, for nothing.”

26 December 1944 | “The trees have vanished from streets and lanes as if by magic. The entire Woodland Plan has been razed, as well as all the trees along the Zuidelijke Wandelweg. The Vondel Park has been locked down to prevent complete annihilation.”

“[...] Char wanted to park her bike outside her piano teacher’s house, but the tree was gone. I’d laugh, if it weren’t so sad. Some kids were standing there, with an axe in hand, offering the tree to passers-by. “Lovely tree, sir! Just five guilders! Free delivery to your home!”

“[...] If it goes on like this, whole houses will collapse. Things are terrible in the Jewish districts. Some houses only have the walls left standing. Doors, floors, beams, stairways, all torn out. Amsterdam’s youngsters have always been destructive, but now they need fuel.”

26 December 1944 | My mom's sister, Charry, writes: “What a wonderful surprise, Thea, when Mrs Langendoen dropped your parcel off at the pharmacy! It was so heavy, I simply couldn’t contain my curiosity and had to open it there and then. I was jumping for joy! What a delight!”

“[...] I wrapped it up again, with letter and all, and didn’t say a word when I got home. Just left it on the table. Mom was out running errands, unfortunately, so she couldn’t share the moment. Papa was just too impatient, ripping it open and almost tearing your letter!”

“Well, that really helped to get us in the Christmas mood, as you can imagine. And would you believe, that very same afternoon, someone dropped off a parcel from Anneke, which also contained butter and some delicious ox meat. Such a special treat!”

26 December 1944 | Charry writes: “Do you have any news of the war? We now know less than ever before and what’s worse is that I really couldn’t care less these days. But that’s wrong of me, isn’t it? I’m just not very optimistic anymore!”

“Remember I told you that my colleague, Cock, had been arrested. She spent a week in prison, along with her mother and sister. But now her father, Matthijs Verkuijl, and her brother and brother-in-law and several others have all been executed. Isn’t it awful?”

“The worst thing is they still haven’t received official notification, even though the men were probably shot ten days before Christmas. How horrid! Her mother turned grey within a week. She knew exactly what was going to happen when she was arrested.”

“They tried to get the men freed, but to no avail. And so thousands are suffering in silence in the Netherlands. People we hear nothing about, unless we happen to know them by chance.”

7 January 1945 | “We never stop discovering things about ourselves in this life and, in general, what we discover is far from satisfying. You too must summon great mercy, Job’s patience and Solomon’s wisdom in your interaction with the girls.”

“[...] The only thing that will have a lasting impact on them is, I firmly believe, an exemplary way of life, truthfulness in word and deed, and strictness in the judgement of one’s own errors and shortcomings.”

“[...] This will ensure that mildness prevails in your judgement of their shortcomings, surpassing your initial, justified indignation. Only if you adopt this way of life, will you succeed in starting each new day with a joyous heart.”

<I've decided to revive this thread, because the situation in Yemen remains dire.>

7 January 1945 | My grandmother to my mother: “I’m sure you’re wondering how things are here. Fortunately, we are very much alive and healthy. The store is busier than ever. We have no worries about money, but everything is still very expensive, if available at all!”

“Yesterday, we managed to lay our hands on a couple of eggs, so that we had something special for Eef’s birthday. Our potato position has improved. A cooperative at the retirement home purchased potatoes and hired a boat. One half arrived safely, the other half vanished.”

“[...] Still, we managed to get 40 kilos of potatoes. Anneke also sent us some from Friesland, but that boat was attacked by an English plane, shot to pieces and unloaded at the Entrepotdok here in Amsterdam. The holes were repaired and the cargo was put back in, but...”

“Our package had vanished, along with many others, of course. After three trips eastward and many disputes, Papa returned home bearing a booty of 17 kilos of potatoes. The skipper eventually just filled Papa’s bag with treasure from the hold. So we feel filthy rich right now!”

<Each trip would have taken about an hour each way. With 17 kilos on his shoulder on the last homeward hike.>

7 January 1945 | “Mrs and Major Hordijk informed us that they regularly, once a week, receive a package by post from Franeker. The maximum weight is 2kg and it regularly arrives exactly on time, containing 1kg of wheat with some buried treasure like sausage, bacon or butter.”

“They give the postman 1 guilder each time he delivers the package, to keep him on the straight and narrow. Is this something you might consider? It would be most welcome, particularly a little fattiness, which is well-nigh impossible to get here, neither for love nor money.”

“Our stash of fat is shrinking fast. See what you can manage, girlie, to keep our spirits up here. Your proposal to join you out there has many drawbacks. The principal one being: our store. If we leave it unguarded, we will return to find it plundered and gutted.”

“And then there’s the trip out there, without suitable transport, carrying all sorts of baggage. Dr Schothorst would, as director of the institution, also have to give permission that Papa could assist with administration and so on.”

“The knowledge that he could be of some use out there is the only thing that might seduce Papa to leave the store unattended. He says that Char and I can go, if we want, but I’m sure you understand that I can’t leave your dear dad on his own here. He simply couldn’t cope!”

“Even working together, it is almost impossible to keep the business running. And yet it is a wonderful thought that we always have the option of heading out to join you, if push comes to shove, especially now we know that Jeanne and Jan will open their darling house to us.”

“That certainly is far more appealing to me than that big house, where it was frightfully cold, even in summer. Char could sleep in your room. But would there be sufficient bedding, I wonder? I ask because it would be difficult to expedite our own, all things considered.”

7 January 1945 | My grandmother rounds off her long New Year’s letter to my mother. | “We are all so attached to our own house and hearth, to our own bed and our own way of life, especially as we grow older. But still we appreciate the chance to escape, should the need arise.”

“Do you know what I forgot to tell you? We managed to get some fuel for the fire by way of trade, which means our fear of being stuck in the cold and not being able to cook our food has now been dispelled, at least for the coming weeks. What a blessing! I could jump for joy!”

“We had to give a lot away in return, but that isn’t so bad, all things considered. We now have something to feed the fire and ourselves. As for the rest, we’ll just have to soldier on. I really must end off now. My arm is lame from writing and it’s well past bedtime.”

“So, dear sweetheart, I wish you lots and lots of love. Be strong, honest, brave and loyal. Keep your languages up to scratch, but try to avoid doing so with questionable institutions. Best you keep those at bay. Wish your co-workers well. And don’t forget to mail us some fat.”

<This is the Elisabeth Wolffstraat where my grandparents had their drugstore, which was at the far end of the street. Not sure when this photo was taken, but the complete lack of bicycles and cars suggests that this may have been sometime during the war.>

14 January 1945 | My mother’s eldest sister, Charry, worked as an apothecary during the war. She writes: “There’s also a lot of acrobatics going on around there, I've heard, to get things running smoothly. I’m sure it must be quite tense, but I know you’re not the nervous type.”

“I wish I could come out and lend a hand, but just last week two of my assistants fell ill at the same time; the first in early January (she lived out way in Oost and they’ve opened a chemist’s there) and Ada, who I told you about, won’t be back for the foreseeable future.”

“The landlord terminated her room and board, claiming lack of food as the reason! So suddenly my abundance of staff has been converted into a shortage, and of course the major winter peak has just begun! We’re working hard, but only from 9 to 4.30, so we’re managing.”

“Had it been until 7pm, what with the terrible cold spell that is upon us, I’m not sure we wouldn’t all freeze to death here! Fortunately, the electric lights have come back on in the Surinamestreet, mainly because the Moffen* have a sawmill around the corner now.” (*Germans)

“They need lights there, so our entire block was turned back on, but when they came round to turn us off again, we managed to get official permission, as an apothecary, to keep our lights. Of course we’ll be exploiting this in more ways than one, if you know what I mean!”

“Speaking of knowing what you mean, did you really think we didn’t know who you were talking about? Come on now! Who do you think we are? Mama just meant you should watch out for provocateurs and the like. We know you’re perfectly capable of looking after yourself, little sis!”

<This is the Surinameplein in 1949. The Surinamestraat is at top, left. My aunt’s pharmacy was probably under the arcade or across street, where there is an identical arcade. The streets in this neighbourhood are all named after Dutch colonies in the West-Indies.>

14 January 1945 | My mother’s eldest sister, Charry, writes: “Had I mentioned that I sleep downstairs nowadays? I just couldn’t get warm upstairs and lay awake for hours with frozen feet. But now I sleep in bed with mama, where it’s nice and warm.” <My aunt was 29 at the time.>

“Papa makes a little nest on the divan every night. He uses all the cushions and says it’s really very comfy. So much so, that I can’t convince him to swap places with me! But let me tell you about the new additions to our food reserves over the past week.”

“Eef twice got a bag of potatoes from the hospital. These were two shipments the municipal medical service arranged for staff. One barge vanished for 14 days and they’d given up hope it would turn up. And Anneke also sent us potatoes and a pack of wheat. Isn’t she sweet?”

“There’s a whole palaver connected to this. Anneke sent it via a private skipper, which was the only option. But that ship was attacked on the way, leaking and half sunk, all the parcels mixed up, hastily unloaded in A'dam, stolen by people on the quay – all sorts of confusion!”

“Papa twice walked out (his bike is being repaired) to the Entrepotdok (out near the zoo!), but he couldn’t find our parcel. After lengthy negotiations, the skipper gave Papa a bag of potatoes he scooped out of the hold. We were over the moon to get them! But that wasn’t all...”

“Early one morning, a lady dropped in at the store and said: ‘I’m the skipper’s sister. There’s a parcel for you. You’d better hurry, because he sets sail this morning!’ So Dad raced over there, but the skipper had already left and he’d taken our parcel with him!”

“The harbour master said: ‘If you run fast, you may be able to catch him at the Oosterdoksluis.’ So Dad raced off again and managed to catch up with the skipper. The parcel contained nearly 30kg of potatoes and a pack of wheat. Unfortunately, the bag was badly torn.”

“But a friendly man lent Dad a bag, just like that, and Dad carried it all the way home on his back. And it was very icy on Tuesday! What a hero! Our new problem is that we don’t have any vegetables! They simply aren’t available at the moment. But we haven’t lost heart!”

<This is the Oosterdoksluis in 1936. The skipper probably had a Frisian cargo barge with a mast, which meant he had to wait for the rail bridge in the background to be raised. The bridge opened at set times, based on the rail schedule.>

Tuesday morning, 16 January 1945 | My grandfather writes to my mother: “Between all my work and domestic commitments, I’ve found time to write to my littlest girl, who is bravely fighting the good fight, not only for herself, but also on behalf of others.”

“We were glad to hear that the situation surrounding Sister Boerema has improved and, if the assurances given to Eef are to be believed, she should be back at the Zwaluwenburg in about six weeks. Let’s hope the experience doesn’t have any permanent effects on her fragile health."

<Sister Boerema was the director of the Zwaluwenburg, the institution for "wayward girls" where my mother was a trainee nurse. Boerema was arrested and imprisoned in December 1944, after several girls ran off and informed the German authorities that they were being abused.>

“How brave of you, dear girl, to shuffle off your sombre mood by taking a long walk in the misty cold. Once the sun starts shining within once more, let it radiate brightly on all around you, because most people don’t have the strength to find joy and balance in these dark days.”

“[...] Things are still very busy in the store. It’s almost impossible to get anything nowadays (no one’s delivering, most of the factories are closed and almost all the warehouses are empty), but our turnover is fantastic. We keep clearing out our stock.”

“If we do decide to join you out there, we won’t have to worry about having a valuable inventory, because there isn’t any! If necessary, we can store our furniture somewhere until we get back. I’ve got to run, dear child, hope this letter finds you well in spirit, soul and body.”

24 January 1945 | My grandmother writes: “How long still? I do hope this whole, bloody conflict would come to an end, so that every creature can breathe easily once more and devote itself to the repair of home and hearth.”

“The destruction in every area of human life is vast and thousands of families will be unable to recover, whether it be morally or spiritually, not to mention the physical and mental suffering they have endured. I do so hope your institution will be left in peace from now on.”

“If the authorities are willing to imprison the director for such spurious reasons, you all run exactly the same risk. According to our laws, she has done no more or less than is expected of her: which is to supervise the care for wayward minors.”

“I hope you have the wisdom to spot danger when it comes and to seek safe refuge before it arrives. That said, I think you will have more pressing matters on your mind in the coming weeks than the lies of unreliable elements within your community.”

24 January 1945 | “The bread ration has been cut by another 200gr. That means we get 800gr (which is one loaf) plus 1kg of potatoes for a whole week. No vegetables, no cheese or any similar supplementary food. We’re just glad you’re eating enough, doing that heavy work.”

“This can’t go on for much longer. People keep plundering bakers’ carts and potato and vegetable shipments. Hundreds of families are trying to find shelter for their children outside the city. But others don’t have that option and older people especially are suffering terribly.”

“It’s freezing here and the city is buried deep under icy snow, which means transport has ground to a near standstill, and that includes the supply into A’dam. All this perfectly suits the starvation strategy in certain circles, allowing them to retain the illusion of goodwill.”

“Our beautiful city is slowly becoming polluted, because the work of the city cleaners has also been disrupted. The dead are left unburied for eight to ten days (and sometimes even longer). Everything is stagnating. How long can this go on?”

4 February 1945 | My mother’s sister Charry writes from Amsterdam: “I miss not having my bicycle, now that it’s a bit warmer. It takes me so much longer to walk to work and back, and walking makes me more hungry. That was the worst thing about the cold! The hunger!”

“Things really were dismal! At least we’re getting a little more now, but it still isn’t enough. The school in our street is now the distribution point for the central kitchen, which means that all day long we have people coming and going, carrying pans and buckets.”

“You can see the hunger etched on their faces! The people really look ragged. To make things worse, the garbage isn’t being removed. People just leave their mess at the roadside. It’s starting to stink already, so you can imagine what it will be like when things get warmer.”

“But the war news really is wonderful, right? We really are enjoying the fact that the Moffen are finally experiencing what it is like to have war in their own country. We hope the allies will keep pressing on now, so that the Germans don’t get a chance to catch their breath!”

“If that means the English will take longer to liberate us, so be it! Although I do hope the battle will be fought outside our little country. Imagine how frightful it would be if they fought for Amsterdam like they’ve been fighting for Budapest!”

<During the Siege of Budapest, the Hungarian capital was surrounded by Soviet forces for 50 days until the German occupying forces capitulated. During the siege, 38,000 civilians died of starvation and military action. Some referred to it as “a Second Stalingrad”.>

5 February 1945 | My grandfather writes: “Dearie. When will you get this letter? If there’s another round of ice and snow, it could take ages before this reaches you. According to Eef, who seems to delight in bringing evil tidings, it will be 20 below around 15 February.

“I feel we’ve had more than enough of this. And we had sufficient fuel for the fire, but countless others had nothing or next to nothing left and they really suffered when the cold came. I’m very, very grateful I managed to trade goods for fuel in December. What a blessing.”

“We have now (better late than never) also started trading other goods that we no longer sell for money: sweets for wheat and potatoes; salt and vinegar for potatoes and vegetables etc. No one in Amsterdam even mentions fat and butter anymore, let alone tastes them.”

"Twice, the Germans took the butter that had been made available for holders of children’s ration stamps, which dated from November and even before that. The only things that keeps Amsterdam going is hearing that the 'East-Asian hordes' are overrunning the ‘Kultuurland’.”

“They are now counting the kilometres that separate them from the ruins of the Reich’s capital. This makes it easier for people to keep their spirits up, to better endure the hunger and cold, than when the war had become bogged down, without any movement.”

Under the banner of

“moral and spiritual rearmament”

we have found one another.

Proletarians and Plutocrats of all nations — unite!

“moral and spiritual rearmament”

we have found one another.

Proletarians and Plutocrats of all nations — unite!

<Dutch communist resistance propaganda, which perhaps aptly has the precise dimensions of a folded business card.>

5 February 1945 | My grandfather continues: “There’s so much going on. There are daily reports of people hijacking potato shipments and bakers’ carts. This is mostly the work of unsavoury elements, with ill-gotten goods being sold on the black market at exorbitant prices.

“A loaf of bread costs 35-45 guilders! Potatoes are sold at 5 guilders/kg (which is cheap). Meat hasn’t become very much more expensive. We buy as much as we can and whatever we can. Meanwhile, we’re doing fantastic business in the store, as long as we can get goods.”

“We can literally sell anything. For example, we had a couple boxes full of kitchen sweetener in sachets. This stuff is called Wonderzoet (Miracle Sweetener), probably because no one could taste that it was actually sweet. But now it has suddenly proved to be very useful.”

“If you use enough, it sweetens the cake and bread people are baking with the rye and wheat they have in reserve, which they're using to supplement their meagre bread rations. We’re selling Wonderzoet 40-50 sachets at a time. Vitamin and calcium products, too!”

“And finally an ‘assignment’ for you, dear child. Next time you’re in Apeldoorn visiting Sister Boerema, would you please visit our laundry and ask them about the last hamper we sent, shortly before “Dolle Dinsdag” (Crazy Tuesday) in September, which must be ‘somewhere’.”

“The hamper (extra-large) is worth at least 1000 guilders, so it really would be worthwhile tracking it down. The laundry’s address is Wasscherij Chr. J. Gijsbers. Hoenderparkweg 48 Apeldoorn. We just want to make sure the goods are safe, for our peace of mind.”

<I have many questions about this “assignment”. Why would someone in Amsterdam send their laundry to Apeldoorn in wartime? How much ‘laundry’ could you get for 1000 guilders in those day? Why leave it there if it’s worth so much? Feel free to add your best guess below.>

<My guess is that the 'laundry' may in fact have been a person in hiding, who needed to be moved. Possibly for a fee of 1000 guilders. But proof? Niks.>

21 February 1945 | My grandmother writes to my mother: “How wonderful that Sister Boerema has been released! But she must remain cautious, because she will be arrested again if the authorities feel there is anything out of the ordinary. And that goes for all of you, too.”

“The main risk is the unreliable nature of many of your girls, whose untruthful representation of the state of affairs is believed by the authorities. This has made your work so much more difficult than before. You have been robbed of the power to educate!”

“Eef is also having a hard time. She works night shifts every three weeks. An endless night from 7 in the evening until 7.30 in the morning, followed by restless sleep during the day, accompanied by regular colds, headaches and stomach cramps.”

“She also hates the long walks. She never liked walking, but now things are deathly quiet and very inhospitable along the way. Dirt and hunger are everywhere on the streets, etched on the faces of many adults and children passing by. I hope this untenable situation ends soon.”

“Hundreds of people are dying of malnutrition. Eef’s hospital is having difficulty storing the corpses. That’s how many people are dying there. Everything is stagnating, with some bodies staying above ground for 4 to 5 weeks before there is a chance to bury them. Isn’t it awful?”

“When things get warmer, there’s a very real danger that contagious diseases will spring up and spread. Fortunately, there is still hope in the hearts of the people, otherwise many more would already have died. But hope springs eternal.”

Amsterdam, 16 March 1945 | “Dearest treasure. We were overjoyed to receive your unexpected letter. Fortunately, I already knew you had returned safely to the Zwaluwenburg, by way of a letter sent to Eef. There was no mention of the journey, but it was proof that all was okay.”

<My mother was driven to Amsterdam by her sister's high-school sweetheart, who had joined the SS and picked her up in a German staff car. The four soldiers took turns sitting on the bonnet to spot RAF fighters strafing the road. My mom asked them to drop her far from home.>

“[...] We got sick after you left. Charry caught a cold at the pharmacy and felt ill. She was running a fever and then became really unwell, with an upset tummy. She lost her appetite completely. She felt better on Sunday, but worse on Monday, and went back to work on Thursday.”

“On Wednesday, I have a massive bout of dysentery, which literally left me as floppy as a tea towel and completely exhausted. Fortunately, this circus lasted just 24 hours and now I feel fit enough to do my share of the communal chores again, for which I am ever so grateful.”

“[...] Well, dearie, that’s all the news I have for you. Sadly, the war isn’t over yet. Oh, I almost forgot the worst news: Uncle Hendrik has been in Scheveningen Prison since early February for hiding Jews. Everything was taken from them: furniture, clothing, bicycles, cash.”

“My sister was released on account of her heart condition, and Tiny managed to escape. She showed up here last week Monday, all the way from The Hague, on a borrowed bike, without any tires, to do some shopping. She went back on Friday. She’s staying with my sister and a friend.”

“Hendrik was to be taken to a concentration camp in Germany, but it remains to be seen if he can be transported. They did what they could to get him out, but to no avail. It really is terrible They’re getting on in years and Hendrik had a busy surgery with an elderly doctor.”

<My granduncle Hendrik Jakobs was a doctor in The Hague. He was married to my grandmother’s sister, Maria van Charldorp. They had given refuge to a Jewish family. Hendrik was captured delivering a message to another address, where other members of the family were hiding.>

<The Jewish families at both addresses were arrested by Kees Kaptein and his notorious team of “Jew Hunters”. The families were imprisoned, but the war ended before they could be transported to the death camps in the East. Granduncle Hendrik was less fortunate.>

<After his arrest, he was imprisoned in Scheveningen and tortured by Kaptein. Later, Hendrik was taken to the prison camp at Leusden near Amersfoort, where he was executed on the 18th of March 1945, two days after my grandmother wrote this letter to my mother.>

<This photo of Hendrik Jakobs was taken in Southern Utah or Northern Arizona in April 1939, when he was visiting my grandmother's other sisters, who had married Mormons and settled in Utah and Ohio in the 1920s.>

<Because I wanted to find out more about Hendrik Jakobs and my grandaunt, I contacted my family in America, who informed me that they had lost contact with my branch of the family when my grandmother died in 1947. The other sisters had always stayed in touch.>

In a letter to her sisters in America, my grandaunt Maria writes about her arrest: “All of a sudden they were there in the room with me. One stood pointing his revolver at me, while the rest did a thorough search of the house. The Jewish family was also found, of course.”

“Because of the sudden raid, there had been no time for them to go to their hiding place. It was a father, mother, two sons, the brother-in-law of the lady, and a son of the latter. The last two arrived on August 24th. The family had asked several times if they could come, too.”

“We turned them down at first, because there were just too many. But on my birthday I said to Hendrik: ‘Let us save the lives of those two people as a birthday present to me, and take them in with us.’ Two days later they had already arrived.”

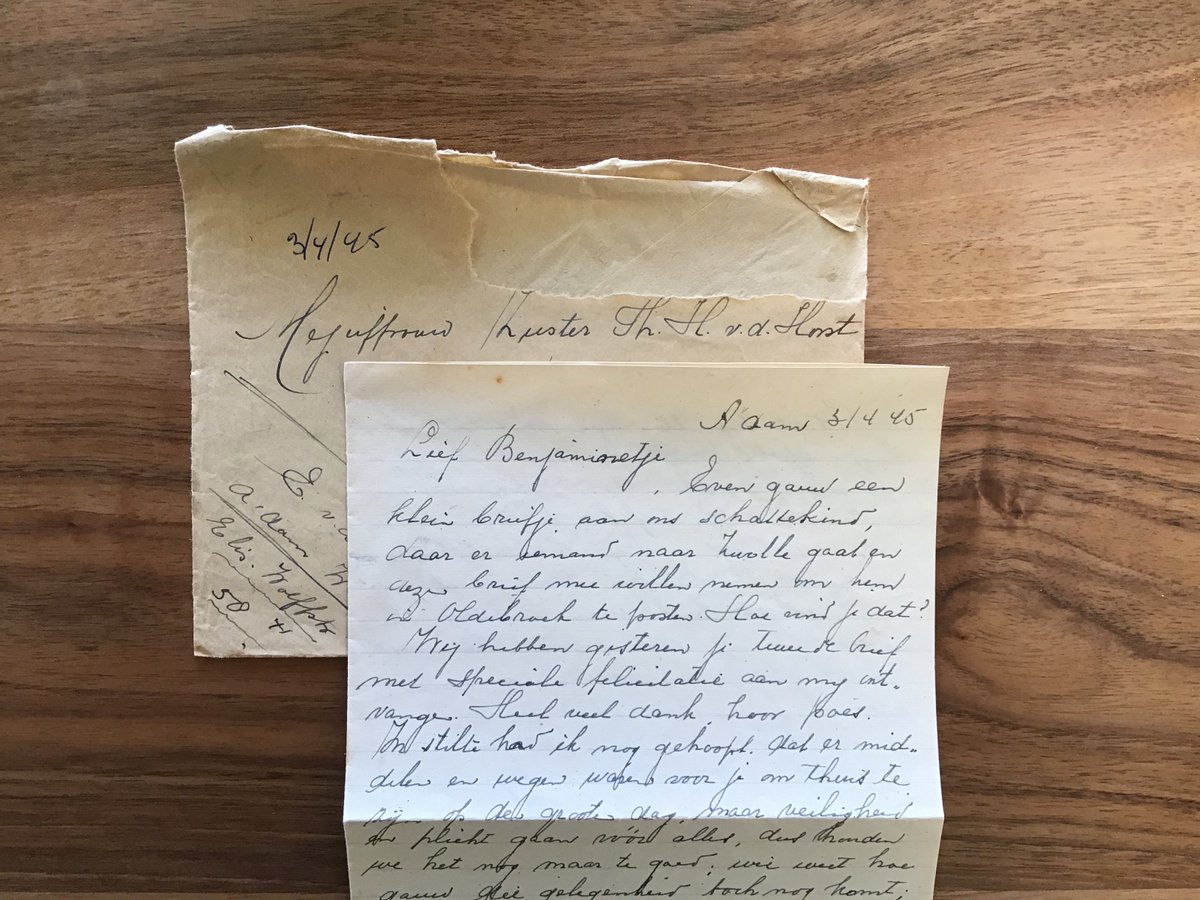

Amsterdam, 3 April 1945 | The war is drawing to a close. My grandmother writes to my mother: “Dear little Benjamin – Just the quickest of notes to our sweet child, as someone who is going to Zwolle has promised to post this for us in Oldebroek. Isn’t that lovely?”

“[...] I'd quietly hoped there would be some means or way for you to be home on the big day, but safety and duty above all else, and so we now have something to look forward to; who knows how soon the opportunity may arise; I sense a spirit of anticipation and delight.”

“The festive spirit is already catching on here. And you know what that means: washing the rugs and curtains; giving furniture an extra polish; cleaning out cupboards etc. All of which heightens the impression of festivity. Unfortunately, we’ve run out of coal.”

“We’re finishing off our wood reserves and doing our best to barter goods for fuel. We're doing pretty well food-wise, but our fat status is poor. Auntie Leen is coming to dinner, but we won’t slaughter our last rabbit yet. If you don’t stay away too long, we’ll save it for you!”

Amsterdam, 3 April 1945 | “Everything is fine here. We’re keeping our spirits up. You too? It’s a good thing you’re so busy and don’t have time to hang your head. Sometimes I miss you a bit, but fortunately I’m so terribly busy with everything, which really is the best medicine.”

“I hope you can read my handwriting. I’m writing quick-quick and Charry is sitting here slicing her bread, which isn’t really helping. I really must end off now, darling, because Char has to leave and will be taking this letter along. Lots of kisses and big, big hug from us all.”

“PS The bacon is a delight! Papa used it to make pancakes, which are on the table in front of me, to supplement our bread rations. The butter was delicious too, but already finished. It’s so much tastier than the stuff we get with ration stamps, which is fat-free and taste-free.”

Meanwhile at the #Zwaluwenburg... | One morning in March 1945, I was called because two young German officers wanted to inspect the house, and I was the only one who spoke German fluently. They explained that they had been instructed to find a way station for retreating troops.

“Feel free to look around,” I said, “but don’t get your hopes up, because this is an institution for ladies and girls, and the whole place is in use. There’s an empty estate near Elburg you could use. Your friends threw hand grenades in there, but it still has walls and a roof.”

The officers didn’t take offense to my remark and calmly explained that the other place was unsuitable, because it was exposed to attack from the air. I nodded and when they left I thought to myself: that’s that, problem solved. But around 3 o’clock I was called again.

I followed the harbinger of doom to the window and saw a well-filled uniform crossing the bridge on foot. Apparently, the senior officers didn’t fully trust the wooden bridge over our moat, because they always left their staff cars on the driveway and walked the last stretch.

When I opened up, he walked right past me without saying a word. So I kept my trap shut and followed him around as he opened and closed doors, inspecting different quarters. I asked if there was anything I could do for him, but he didn't say a word.

He opened the door to one of the rooms, where Sisters Bertha and Mien were doing needlework with a group of girls. Bertha looked up, but said nothing, and we went silently on our way, the officer and I. There were nurses and patients everywhere, but he ignored them all.

I answered all the quizzical glances with a shrug. And once we had seen the whole house, we headed down the steps towards the garage. We still hadn’t said a word to one another. But suddenly I felt my heart shrivel in my chest: the horses!

Behind our garage, we had three stables and because the farmers’ horses were still being confiscated and it was too cold to keep them in the woods, the farmers had hidden their horses with us. My only hope was that this was a quartermaster and not a horse rustler.

He stepped into the garage, which had once been the coach house, and saw the two horse boxes, which had probably been for the carthorses, and triumphantly spoke his first words: “Ahaa! Pferde!”

“Well spotted,” I said, "but there are no horses here. Look. Just firewood drying."

“Well spotted,” I said, "but there are no horses here. Look. Just firewood drying."

He walked through the garage to the back door. If I didn’t distract him, he would keep going, step outside and probably smell the horses in their stables. I realised he was so arrogant he would probably do the exact opposite of what I suggested, but he was almost at the door.

So I said, as nonchalantly as possible: “If you go through that door, you’ll find the garden you just saw from the first floor.” He nodded curtly and turned back. With trembling knees I followed him out of the garage and across the courtyard to the other wing.

He walked through the garage to the back door. If I didn’t distract him, he would keep going, step outside and probably smell the horses in their stables. I realised he was so arrogant he would probably do the exact opposite of what I suggested, but he was almost at the door.

So I said, as nonchalantly as possible: “If you go through that door, you’ll find the garden you just saw from the first floor.” He nodded curtly and turned back. With trembling knees I followed him out of the garage and across the courtyard to the other wing.”

<The Zwaluwenburg Estate is still much the same today as it was during the Second World War.>

Having returned to the foot of the stairs, the officer turned to me, raised two fat fingers and said: “Zwei.”

I had no idea what he meant.

“Zwei stunden.”

He was giving us two hours to vacate the house.

He turned to leave.

“Und was...” I said angrily.

He turned back.

I had no idea what he meant.

“Zwei stunden.”

He was giving us two hours to vacate the house.

He turned to leave.

“Und was...” I said angrily.

He turned back.

“Und was do you expect us to do with the patients for whom we are responsible? Do you realise we cannot transport them? Would you like us to leave them alongside the Zwolle-Amersfoort road or the Apeldoorn road? Shall we drop them in a ditch to wait until the war is over?”

We stared at each other for a moment. Then he said: “Come,” and mounted the steps for a second inspection. He asked me how many people lived in the house and counted how many of them slept downstairs. This time round he took a longer look in each room.

He gave me a chance to point out the leaking buckets by the toilets and the fact that we had no electricity. He turned a tap and flicked a switch, and when I told him we’d had no heating during the past winter, had asked where we fetched our water and how we prepared our food.

When I told him that we couldn’t prepare our own food anymore and that we had to fetch it at the soup kitchen in Elburg, which was an eight-kilometre walk every day, the officer looked suitably concerned. The well-filled uniform and I were starting to understand each other.

“The two nurses staying in the attic must remove their personal belongings, because those quarters will be for the officers,” he said. “And please take everything you need from the ground floor up to the first floor. Only the office downstairs, on the left, must remain as it is.”

“You can make use of the first floor, but the attic and everything else downstairs, with the exception of the gardener’s quarters, must be made available to the Wehrmacht. Is that clear?

It was clear, and he had a good eye. It was going to be a challenge, but not impossible.

It was clear, and he had a good eye. It was going to be a challenge, but not impossible.

“And the kitchen?” I asked. “We can’t heat anything upstairs.”

“You can make use of the kitchen, but I don’t want any patients down here.”

"I'll be in charge of the kitchen," I said, "We'll need to fetch water, but that will always be done under staff supervision.

“You can make use of the kitchen, but I don’t want any patients down here.”

"I'll be in charge of the kitchen," I said, "We'll need to fetch water, but that will always be done under staff supervision.

“That’s acceptable,” he said.

"Will your cook and assistants also fetch water for me, and can you guarantee that there won’t constantly be people walking in an out?" I asked

“The kitchen will be out of bounds for everyone except the kitchen staff and high-ranking officers.”

"Will your cook and assistants also fetch water for me, and can you guarantee that there won’t constantly be people walking in an out?" I asked

“The kitchen will be out of bounds for everyone except the kitchen staff and high-ranking officers.”

We’d have to wait and see whether his men followed orders, but at least we didn’t have vacate the place! And I’d saved three horses! When the officer disappeared from view, I ran straight to the gardener to say that the farmers needed to come and fetch their horses immediately.

Then we went in to see the matron to convince her we needed to get cracking. It was a major operation, trying to find space for all the patients and all the nurses who slept downstairs. And then came the next problem: Truus had two rabbits – Hollanders – hidden in the garden.

Truus was sure the soldiers would find the rabbits. “They’ll end up in a stew!”

“Put their run under the kitchen window,” I said. “I’ll keep an eye on them.”

The very next day the first group of retreating soldiers arrived on foot.

“Put their run under the kitchen window,” I said. “I’ll keep an eye on them.”

The very next day the first group of retreating soldiers arrived on foot.

It is March 1945 at the #Zwaluwenburg. My mother reports:

They were on foot, clearly tired, and when I saw them from nearby, they looked far too old to be playing at soldiers, and clearly they felt much same.

I was busy in the kitchen and heard men speaking outside.

They were on foot, clearly tired, and when I saw them from nearby, they looked far too old to be playing at soldiers, and clearly they felt much same.

I was busy in the kitchen and heard men speaking outside.

The three of them were standing around the rabbit hutch.

“Good morning,” I said, stepping outside.

They greeted me and asked if the rabbits were mine.

“No, they belong to my colleague,” I replied.

“Holländer,” he said gently. “I had some, too."

He paused.

"Gone. All gone."

“Good morning,” I said, stepping outside.

They greeted me and asked if the rabbits were mine.

“No, they belong to my colleague,” I replied.

“Holländer,” he said gently. “I had some, too."

He paused.

"Gone. All gone."

Because I wanted to console him, I told him about Truus’s fear that her rabbits would end up in a stew.

The three of them chorused: “Never! Never!”

I asked them what division they were with, but they didn’t seem to know.

The three of them chorused: “Never! Never!”

I asked them what division they were with, but they didn’t seem to know.

They told me they were all workers whose factories had been bombed or closed. They had been issued old uniforms and they pointed out where they had been repaired and stained. I’m pretty sure they had little or no idea where they were.

Because I had to go back to work, I asked them to keep an eye on the rabbits.

They sat down around the hutch, clearly honoured by the faith I had in them.

How could I hate these poor buggers?

They departed the next day. Not marching, singing soldiers, but shuffling boys.

They sat down around the hutch, clearly honoured by the faith I had in them.

How could I hate these poor buggers?

They departed the next day. Not marching, singing soldiers, but shuffling boys.

<The lad in the photos is 16-year-old Hans-Georg Henke, who was captured by the US 9th Army in Germany on 3 April 1945>

March 1945 | The retreating Wehrmacht are using the #Zwaluwenburg as a way station. My mother reports:

The next lot were completely different! They arrived in three open armoured cars (much like Jeeps) and an ambulance!

The next lot were completely different! They arrived in three open armoured cars (much like Jeeps) and an ambulance!

<Beppie, committed to the institution by her family, saw the soldiers arriving. “There were about 300! One of the cars had a red cross on the roof. Very scary! But we had a laugh, too! We expected to see wounded soldiers, but they brought out a live calf for the slaughter!”>

<Back to my mother...> I intercepted two officers who were heading for the front door. None of the first group had entered the main house, but this groups consisted entirely of officers and NCOs, so I showed them around the ground floor and explained about the water and lights.

I heard one of them say: “This really is incredible.”

There were paintings on the walls and a superb antique cupboard in the room, but when I turned around to see what he was admiring, I found him looking at me through his binoculars!

There were paintings on the walls and a superb antique cupboard in the room, but when I turned around to see what he was admiring, I found him looking at me through his binoculars!

I glanced at his fellow officers and asked: “How old is that child? I hope he isn’t playing at being a doctor.”

This group was accompanied by a Hungarian chef, almost certainly a collaborator, who must have been quite disillusioned by his choice at this point of the war.

This group was accompanied by a Hungarian chef, almost certainly a collaborator, who must have been quite disillusioned by his choice at this point of the war.

I sent him to tell the officers that I’d been promised help, because of the water situation, and they sent a junior officer. Then Maaike came in with two NCOs she'd found wandering around the upper floors of the house. She didn’t speak German, so she had no idea what they wanted.

“We’d heard there were two attic rooms available,” they explained. but they were occupied.”

Apparently, Matron Bertha had given permission to reoccupy the rooms, because the first group hadn’t used them.

Goddammit! That woman caused more trouble than the entire German army!

Apparently, Matron Bertha had given permission to reoccupy the rooms, because the first group hadn’t used them.

Goddammit! That woman caused more trouble than the entire German army!

Maybe my reaction was excessive, but the preceding days had really put me on edge, so I kept ranting and raging and eventually ended off with something like: “But when push comes to shove, it’s up to me to arrange every damn thing with these guys!” But I used the word “kerels”.

As Maaike went off to make the bedrooms available, one of the Germans approached me and said that he objected to me using the word “kerel” in reference to them. That was a very, very bad idea. I exploded: “Were you appointed to teach me my own language?!”

“Do you really think the Dutch word ‘kerel’ means the same as the German ‘KERL’?!”

That shut him up and they skulked out, leaving me to get on with my work. Apparently, they didn’t need to do any cooking that evening, so I had the kitchen to myself.

That shut him up and they skulked out, leaving me to get on with my work. Apparently, they didn’t need to do any cooking that evening, so I had the kitchen to myself.

We return to the #Zwaluwenburg. It is still March 1945. My mother reports:

The third group arrived a few days later. We could hardly believe our eyes. The soldiers who emerged from the trucks looked like they were fresh out of high school. As if they were on a school trip.

The third group arrived a few days later. We could hardly believe our eyes. The soldiers who emerged from the trucks looked like they were fresh out of high school. As if they were on a school trip.

I don’t recall a commanding officer, but they didn’t need one, they were so disciplined. All drilled in the “Hitlerjugend” programme, no doubt. They spent the night, but didn’t make use of the kitchen. The lads were keen to explore. Our rabbits remained a firm favourite.

They were the newest recruits, they told me, and they thought they were on their way to Arnhem.

“But then you’re going towards the advancing troops!” I said.

They seemed to be very nonchalant about this. At least, the ones I spoke to.

“But then you’re going towards the advancing troops!” I said.

They seemed to be very nonchalant about this. At least, the ones I spoke to.

It was a disgrace that they would use these young kids to fight a lost battle against men who had fought all the way from Normandy, through France and Belgium and the Southern Netherlands.

Cautiously, I told them the previous groups thought the war was practically over and were retreating towards the Western Netherlands. But the lads confidently explained that the Führer would soon reveal a secret weapon that would change the course of the war, ensuring victory!

I gave up. The V1 rockets had sowed terrible destruction, and the V2 was even more powerful apparently, but it came too late. The RAF had perfected its cooperation with the resistance and destroyed German launch platforms in the Netherlands before they could be used.

When they drove off the next day, I could only hope the information about their destination was as much a lie as the propaganda about their secret weapon.

<Adolf Hitler with Nazi party Hitler Youth at a 1935 gathering. | Credit: Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images>

<Adolf Hitler with Nazi party Hitler Youth at a 1935 gathering. | Credit: Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images>

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh