A really beautiful model👇, imo.

Explains so much about the human experience—our thoughts, feelings, & behavior—with so little.

Let me summarize the model, what it explains, and what it teaches us about good modeling in the social sciences.

(Thread)

shorturl.at/mvM57

Explains so much about the human experience—our thoughts, feelings, & behavior—with so little.

Let me summarize the model, what it explains, and what it teaches us about good modeling in the social sciences.

(Thread)

shorturl.at/mvM57

Some puzzles the model helps explain:

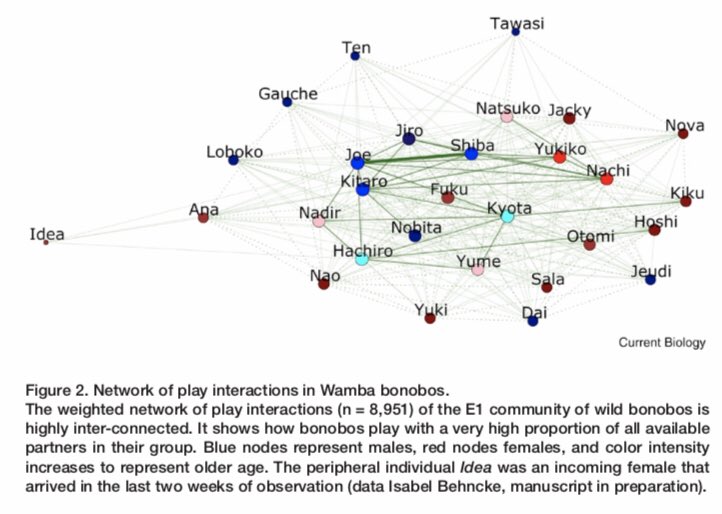

Bonobos, like us, spend an inordinate amount of time playing—hanging out and doing ow seemingly wasteful, but “fun” activities. Some might be learning.

But much is best described as “bonding.”

Bonobos, like us, spend an inordinate amount of time playing—hanging out and doing ow seemingly wasteful, but “fun” activities. Some might be learning.

But much is best described as “bonding.”

We too spend inordinate amounts of time “hanging out” w/ colleagues and neighbors, at the dive bar after work or backyard bbq’s on weekends.

Why do we waste the time? Why is this needed to “bond”?

Why do we waste the time? Why is this needed to “bond”?

Not to mention:

Often such bonds start ~randomly, & persist when shared interests don’t. Eg we stay friends with our high school buddies who stayed religious & remained in our small home town.

Why not lose the baggage? And find friends that are a better fit?

Often such bonds start ~randomly, & persist when shared interests don’t. Eg we stay friends with our high school buddies who stayed religious & remained in our small home town.

Why not lose the baggage? And find friends that are a better fit?

Something similar happens in romantic relationships.

We spend months “falling in love.”

-Giving sentimental (ie useless) gifts.

-Taking long walks around parks, on beaches.

-Staring into each other’s eyes, holding hands.

-Sharing candlelight dinners, at fancy restaurants, where little, if anything, is discussed.

Why do we bother?

-Giving sentimental (ie useless) gifts.

-Taking long walks around parks, on beaches.

-Staring into each other’s eyes, holding hands.

-Sharing candlelight dinners, at fancy restaurants, where little, if anything, is discussed.

Why do we bother?

Not just bother, of course.

We enjoy doing this stuff. It’s some of the most enjoyable moments in life. Some of our best memories. For many, our raison d’etre. That which brings life meaning and makes it worth living.

But why? It’s so wasteful.

We enjoy doing this stuff. It’s some of the most enjoyable moments in life. Some of our best memories. For many, our raison d’etre. That which brings life meaning and makes it worth living.

But why? It’s so wasteful.

Why not just find the partner most compatible w/ you, or the highest quality mate willing to mate w/ you, and get to it.

Why the need/desire for romance and lengthy, expensive, time consuming courtship?

Why the need/desire for romance and lengthy, expensive, time consuming courtship?

And why do we find it hard(er) to make babies, or other long term commitments, w/ people we didn’t have such romance and courtship w/?

How does the romancing make the baby making/long term committing more likely to work? Make us more liable to “stick it through”?

(Or does it?)

How does the romancing make the baby making/long term committing more likely to work? Make us more liable to “stick it through”?

(Or does it?)

And why do other cultures find this less important/necessary?

(See: arranged marriages. And the corresponding lack of extensive courtship. But its own form of love. Eg )

(See: arranged marriages. And the corresponding lack of extensive courtship. But its own form of love. Eg )

Romance, love, and camaraderie are deeply felt. Substantiated by emotions.

But we see similar puzzling behaviors just as often among the highly strategic, conniving, and machievelian.

The LBJ’s, Caesar’s, Talleyrand’s, and Thomas Cromwell’s of the world.

But we see similar puzzling behaviors just as often among the highly strategic, conniving, and machievelian.

The LBJ’s, Caesar’s, Talleyrand’s, and Thomas Cromwell’s of the world.

(Which imo, along with the bonobo example, suggests the need for an explanation that works for conscious optimization *as well as* subconsciously learned or evolved emotions and intuitions.)

These statesmen— among the most conniving people in history—were also quite conscious of who they did favors for.

And how they treated people who they had favored, or who had favored them.

No “irrational” emotions like love or friendship necessary.

And how they treated people who they had favored, or who had favored them.

No “irrational” emotions like love or friendship necessary.

Favors they very much expected would be reciprocated, create alliances, and increase their power.

Even w/ fellow machiavellians.

Even w/ fellow machiavellians.

They would often talk about making someone “beholden” to them. Or being beholden themselves.

But why?

All these men were equally conniving and strategic. Why not take the favor and not return it?

But why?

All these men were equally conniving and strategic. Why not take the favor and not return it?

Now you might be thinking this is just standard tit-for-tat, reciprocity, I help you so that you will help me so that I’ll help you...

Which no one benefits from breaking.

But that doesn’t quite capture what’s going on.

Which no one benefits from breaking.

But that doesn’t quite capture what’s going on.

LBJ has to throw a favor down first. And the person he gives the favor to can take it and walk.

He doesn’t *need* to continue interacting with him.

There are other congressmen he can work for. Or other people he can lobby. Or others to build a coalition w/ in congress.

He doesn’t *need* to continue interacting with him.

There are other congressmen he can work for. Or other people he can lobby. Or others to build a coalition w/ in congress.

And perhaps even more surprising: after LBJ has done *you* a favor, *he* is more likely to be trustworthy *toward* you.

Toward you. That’s a weird direction.

No?

Toward you. That’s a weird direction.

No?

To recap the puzzles:

-Friendship, romance, alliances.

-Bonobos & people.

-Strategic & emotional.

-Gifts. Drawn out, time consuming courtships. ”Hanging out.”

-(Near) random beginnings & persistent beyond pertinent.

-Affects even the one who paid the cost (when only one did).

-Friendship, romance, alliances.

-Bonobos & people.

-Strategic & emotional.

-Gifts. Drawn out, time consuming courtships. ”Hanging out.”

-(Near) random beginnings & persistent beyond pertinent.

-Affects even the one who paid the cost (when only one did).

Now onto the game theoretic explanation.

The key insight:

If you can easily exchange one partner for another, no partner has much reason to think you will be there when (s)he needs you.

Cause if you screw ‘em, you can just replace them.

The key insight:

If you can easily exchange one partner for another, no partner has much reason to think you will be there when (s)he needs you.

Cause if you screw ‘em, you can just replace them.

IOW:

Tit-for-tat (standard “reciprocity”) is no longer self-sustaining, when partners can be easily replaced.

That’s the fundamental problem w/ a free & open marketplace (of friends, mates, allies): you can’t trust anyone.

We become exchangeable. Which makes us unreliable.

Tit-for-tat (standard “reciprocity”) is no longer self-sustaining, when partners can be easily replaced.

That’s the fundamental problem w/ a free & open marketplace (of friends, mates, allies): you can’t trust anyone.

We become exchangeable. Which makes us unreliable.

Except:

What if no one trusts anyone *until* one has sacrificed for the other?

And everyone sacrifices for another, almost at random, when they need to form such a trusting relationship?

That will be our proposed “equilibrium.”

What if no one trusts anyone *until* one has sacrificed for the other?

And everyone sacrifices for another, almost at random, when they need to form such a trusting relationship?

That will be our proposed “equilibrium.”

Which is funny and weird.

But that’s what game theory does.

It takes simple, verifiable assumptions (ability to freely exchange partners) and yields ow inexplicable conclusions (we waste to build relationships, trust those we happen to have wasted for or have wasted for us...)

But that’s what game theory does.

It takes simple, verifiable assumptions (ability to freely exchange partners) and yields ow inexplicable conclusions (we waste to build relationships, trust those we happen to have wasted for or have wasted for us...)

Another way to put it:

G.T. takes puzzling strange behaviors/emotions/tastes, and tells us which simple, verifiable, realistic assumptions (in terms of incentive structure, informational structure, interaction structure) suffice to explain.

G.T. takes puzzling strange behaviors/emotions/tastes, and tells us which simple, verifiable, realistic assumptions (in terms of incentive structure, informational structure, interaction structure) suffice to explain.

And knowing what assumptions *suffice* to explain phenomena tells us when to expect it. And how it will work. And better characterize what exactly “it” is.

All the things a good “explanation” gives you. A good theory provides.

All the things a good “explanation” gives you. A good theory provides.

With the only presumption needed to make the game theory applicable:

People will deviate, if they can benefit from doing so.

People will deviate, if they can benefit from doing so.

Either via conscious strategic “rational” choice.

Or via emotions, intuitions, and preferences adapting. Via learning or evolution.

(That’s why it works for emotions and intuitions, kids and chimps, as well as Talleyrand and LBJ’s!)

Or via emotions, intuitions, and preferences adapting. Via learning or evolution.

(That’s why it works for emotions and intuitions, kids and chimps, as well as Talleyrand and LBJ’s!)

Let’s verify our proposed equilibrium does the trick. Utilizing this one key feature game theory rests on.

Does anyone benefit from deviating from the proposed equilibrium (sacrificing when need relationship, trusting and being trustworthy iff one has sacrificed for the other and neither has yet done ow)?

And why is the more obvious, efficient thing (noone wasting, everyone partnering freely) something we *would* deviate from?

Notice:

If everyone acts according to the purported equilibrium, you still wanna make an initial sacrifice when in need of a relationship, provided healthy trusting relationships are of sufficient value.

Check.

If everyone acts according to the purported equilibrium, you still wanna make an initial sacrifice when in need of a relationship, provided healthy trusting relationships are of sufficient value.

Check.

And you won’t want to skrew over anyone you are in such a relationship w/, lest you have to start from scratch, and make a whole new sacrifice to build one.

Which in turn enables you to trust others once you are in such a relationship w/ them.

Check.

Which in turn enables you to trust others once you are in such a relationship w/ them.

Check.

And you won’t want to skrew over anyone you are in such a relationship w/, lest you have to start from scratch, and make a whole new sacrifice to build one.

Which in turn enables you to trust others once you are in such a relationship w/ them.

Check.

Which in turn enables you to trust others once you are in such a relationship w/ them.

Check.

We can now ask: *when* will the above logic work?

And what more does *that* teach us?

(A key benefit imo of game theory models: the necessary assumptions tell you *when.*)

And what more does *that* teach us?

(A key benefit imo of game theory models: the necessary assumptions tell you *when.*)

Well for one: if society restricts your ability to replace your partner. No need for these prolonged romantic courtships.

See again: arranged marriages.

See again: arranged marriages.

Likewise for friends (or allies romantic partners), that aren’t really expected to be reliable, or where trust ain’t crucial.

(Eg one night stands. Business partners w/ contractual relations).

(Eg one night stands. Business partners w/ contractual relations).

No need for a strong sense of love, affection, or camaraderie in such cases, which after all just goad us into acting according to the above described equilibrium.

The model also tells us that this sense of love/affection/comeraderie will depend on the *lack* of benefits you get at time of initial sacrifice.

(Important distinction: Real not psychological benefits!)

(Important distinction: Real not psychological benefits!)

For instance: mutual attraction and courtship that *can’t* be consummated.

As in “in the mood for love.” “Lost in translation” and “five feet apart.”

As in “in the mood for love.” “Lost in translation” and “five feet apart.”

The love in these films is supersized. (Which makes for a good romantic flick.)

*Because* the sacrificial behaviors (the extensive courtship) don’t reap (sexual) rewards.

*Because* the sacrificial behaviors (the extensive courtship) don’t reap (sexual) rewards.

Odd. Hard to predict w/o game theory.

(Love *more* if yields *less*.)

But with the game theory, not odd. Exactly what you would expect.

(Which is what makes the game theory useful. IMO.)

(Love *more* if yields *less*.)

But with the game theory, not odd. Exactly what you would expect.

(Which is what makes the game theory useful. IMO.)

To summarize/conclude:

The puzzles:

-courtship, play <—wasteful

-favors, courtship play —> trusting relationship.

-maintained even if started ~randomly, regardless who made sacrifice. Or if fit still good.

The puzzles:

-courtship, play <—wasteful

-favors, courtship play —> trusting relationship.

-maintained even if started ~randomly, regardless who made sacrifice. Or if fit still good.

The model:

-assumes people (or their intuitions, emotions) will deviate if can benefit from doing so

-assumes partners plentiful/exchangeable (not true eg w/ arranged marriages!)

-assumes people (or their intuitions, emotions) will deviate if can benefit from doing so

-assumes partners plentiful/exchangeable (not true eg w/ arranged marriages!)

-concludes: sacrifice (by at least one side. eg when courtship -/->sex) needed for trusting relationship. Then self-sustaining (<—even if random at first, imperfect fit now).

What makes this a *good* model?

-explains ow inexplicable

-assumptions clear, reasonable, easy to check/verify

-yields new predictions (when assumptions fail!)

-math used for robustness/generality. Not obfuscating what’s driving what, or creating artificial result

Eom

-explains ow inexplicable

-assumptions clear, reasonable, easy to check/verify

-yields new predictions (when assumptions fail!)

-math used for robustness/generality. Not obfuscating what’s driving what, or creating artificial result

Eom

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh