A thread based on slides I am presenting at @theNASEM on Oct 10. This is part of advising for the National Institute of Aging as it plans funding programs for the primary prevention of #dementia and #Alzheimer's Disease. Here we go...

@theNASEM Exercise has been shown to be perhaps the most effective neuroprotective intervention. This evidence is mainly based on animal research but some has been corroborated by human studies. At this point, no other intervention can claim the same conglomeration of benefits on the brain

According to a meta-analysis in 2018 exercise has a medium positive effect on cognition in individuals with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's. However, most studies are small and some effects seem implausibly large.

These results follow the unforgettable conclusion of the 2010 @NIH consensus meeting, in which exercise was grouped alongside "other leisure activities" such as painting and religious services, intentionally or unintentionally giving the impression that the evidence is similar.

Likewise, who can forget the 2011 review commissioned by the @CDCgov, which could not find evidence that exercise can improve cognition in older adults. The "multidisciplinary panel" did not include researchers from exercise science.

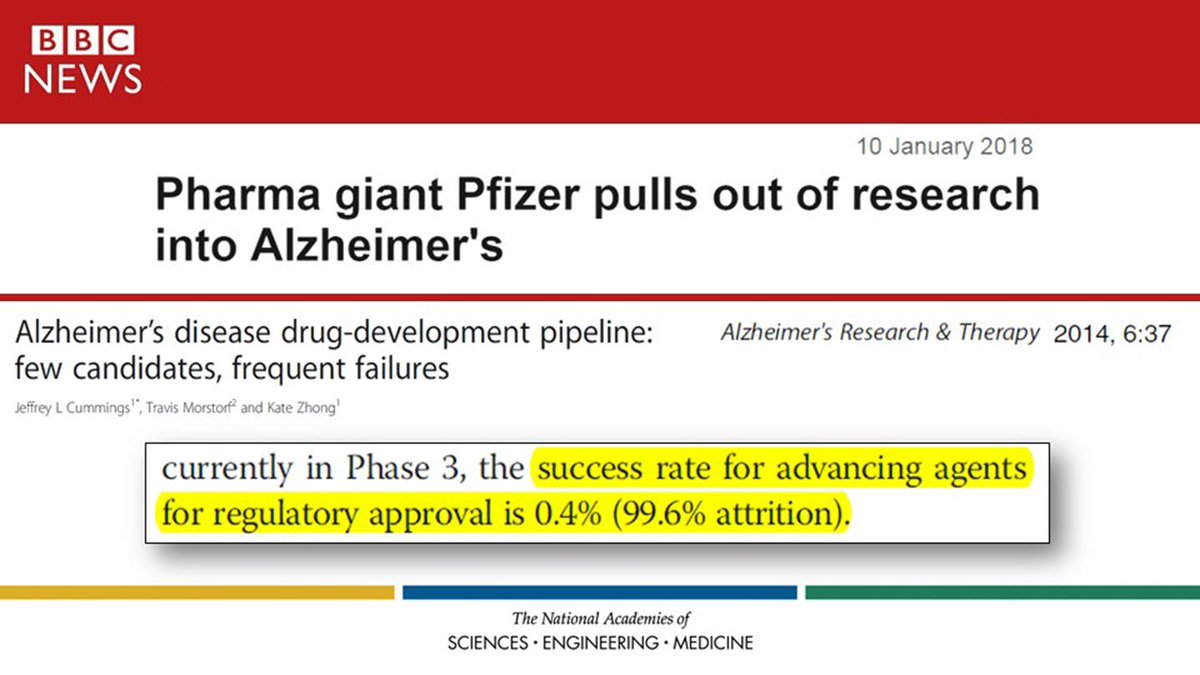

At this point, we're facing a new reality because most major pharmaceutical companies have pulled out of the race to find a drug for Alzheimer's Disease, after having an astounding 99.6% failure rate. Perhaps the problem is the long fixation on the "amyloid cascade hypothesis."

Which brings us to the amazing study by Choi et al. (2018) in @ScienceMagazine, which basically said that a good way to move forward in new drug development would be to try to ...mimic the effects of exercise. Or, you know, getting people to exercise might be a good option too...

In my mind, it is crucial to take advantage of biomarkers, such as PiB PET. Once amyloid buildup has taken place, this should be considered the treatment phase. Once cognitive symptoms have appeared, it's probably already too late to intervene.

According to estimates, by the time symptoms such as memory loss appear, amyloidosis has "maxed out" and there is atrophy, measurable by volumetric MRI and FDG-PET. This is why I think recruiting patients with Alzheimer's diagnosis or even Mild Cognitive Impairment is too late.

So, let's look at the current approach to encourage physical activity among older adults. The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines follow the same approach as always: (1) try to convince old folks it's good for them, (2) give them specific numerical targets they need to achieve.

Let's look at each part separately. "Do it, it's good for you" reflects reliance on the fundamental assumption of rationality. If you give people the "right" information (enough, correct, compelling), they must act since they are rational creatures interested in their health, no?

So, at this point, all our exercise-promotion interventions are based on the use of information designed to appeal to people's rationality in one way or another (e.g., cultivate risk appraisals, convince that benefits outnumber barriers, boost self-efficacy).

By doing so, the promotion of exercise and physical activity has fallen behind the times by a couple of decades. We have yet to discuss the issue of "bounded rationality" that has been recognized in other disciplines. And we have yet to discuss "heuristics and biases." Why?

Meanwhile, there are intriguing indications that exercise may be unique among health behaviors in that knowledge of its benefits is almost entirely disconnected from the propensity to engage in the behavior: 97% of Americans know it's good for them, yet 97% don't do enough of it.

And our interventions seem to be only borderline effective. But the effectiveness drops with larger samples, longer follow-ups, and trials of higher methodological quality. At this point, the average effect seems to be around 0.20 of a standard deviation, a "small" effect.

To put this number into perspective, that's also the effect of the so-called "question-behavior effect" or "mere measurement effect," namely the apparent change in (mostly self-reported) behavior as a result of just inquiring about the behavior by administering a questionnaire.

And, a dirty little secret is that which of our time-honored theories one uses as the basis of the exercise- or activity-promotion intervention makes little to no difference.

And, in fact, using a psychological theory or not using a psychological theory also does not seem to make a difference. Oh my!

Let's also talk about the 2nd part of physical activity guidelines: "this is how much you should be doing." This is based mainly on information from epidemiologic (i.e., correlational) studies. A recommendation is given that balances benefit (risk approaches a plateau) and risk.

Using the balance of "benefit" and "risk" to decide dosage follows the reasoning used in developing pharmaceutical prescriptions. But exercise is a behavior people must perform willingly. So, what's missing? Perhaps the "affect heuristic"?

Perhaps, in addition to our cognitive appraisals, we also need to consider the role of affective constructs such as pleasure and enjoyment. In the last several years, researchers have been trying to find ways to make exercise more pleasant. It's not easy but it may be possible.

Can "affect" be measured? Yes, although this may be one of the most convoluted and confusing domains of psychological theory and assessment. I have tried to do my part by putting together a century's worth of literature into a short and readable guidebook. I hope it can help.

Moreover, with researchers from around the world, we have been able to decipher the dose-response relation between exercise intensity & affective responses. This discovery now allows us to build a three-legged stool, if we wish: (1) benefit, (2) risk, AND (3) pleasant experiences

And, we would be remiss if we din't mention that the activation of the endocannabinoid system (which may, to some extent anyway, underlie positive affective responses to exercise) may be required or at least may be involved in the upregulation of neurotrophins such as BDNF.

The first interventions designed to manipulate affective responses to examine the effects on long-term exercise or physical activity behavior have started to appear, with promising results. The studies are still small because funding is still in short supply. Change takes time...

So, with @RalfBrandGER, we have proposed the Affective-Reflective Theory (ART), according to which it is not sufficient to change the cognitive appraisals postulated by our current theories. It is also necessary to cultivate positive affective associations of "exercise."

@RalfBrandGER Thank you for reading.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh