1. It's a little known fact, but the great depression included one of the greatest rises in professional design jobs in history.

In 1931 there were 3500 industrial designers in the U.S. By 1935 it almost tripled to was 9,500.

#designmtw #design #ux

In 1931 there were 3500 industrial designers in the U.S. By 1935 it almost tripled to was 9,500.

#designmtw #design #ux

2. This movement to hire designers was led by the automotive industry - Alfred Sloan's recognized GM that needed to be designed by designers.

In the late 1920s cars looked similiar w/ similiar features.

GM competed by improving styling, features and engines, by design.

In the late 1920s cars looked similiar w/ similiar features.

GM competed by improving styling, features and engines, by design.

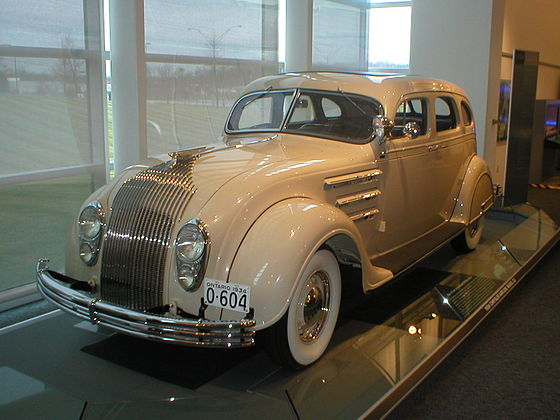

3. This was also the rise of streamlining as as style (not just in cars, but in everything).

It was a way to make the emotional appeal through style of a product, something engineers and businessmen couldn't conceive of on their own.

(1934 Chrysler Airflow)

It was a way to make the emotional appeal through style of a product, something engineers and businessmen couldn't conceive of on their own.

(1934 Chrysler Airflow)

4. Designers didn't only contribute style but the spirit of constant improvement in functionality came with them.

The first automatic transmissions, power steering systems were part of a soon to be constant wave of design improvements, novel at first but soon near standards.

The first automatic transmissions, power steering systems were part of a soon to be constant wave of design improvements, novel at first but soon near standards.

5. Of course some "style 4 style" choices went too far. Famously in the 1950s tail-fins arrived.

Designer Harley Earl pioneered them. They served no functional purpose (and were dangerous). They didn't last long.

"Tailfinning" is still design slang for 'superficial gloss'.

Designer Harley Earl pioneered them. They served no functional purpose (and were dangerous). They didn't last long.

"Tailfinning" is still design slang for 'superficial gloss'.

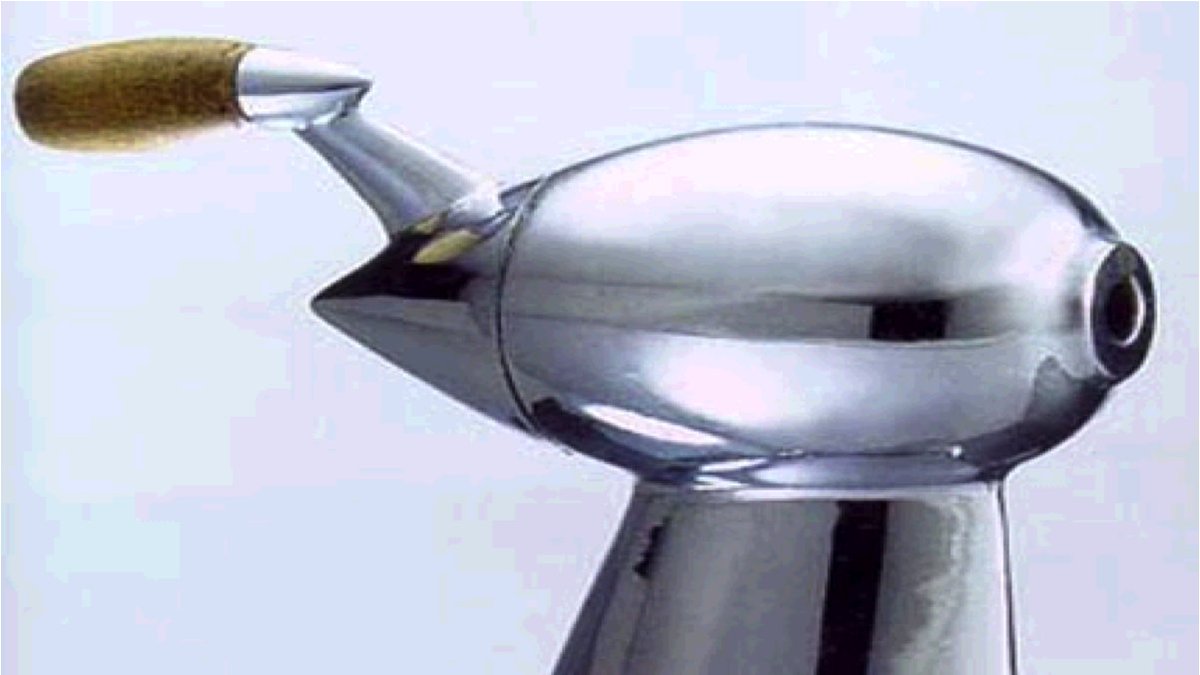

6. Absurd "aerodynamics" went into other products too.

Raymond Lowry's pencil sharpener, never produced, is a staple in design museums.

But since the sharpener doesn't move it's absurd to shape it this way. It's a kind of postmodernism - the form and function are juxtaposed!

Raymond Lowry's pencil sharpener, never produced, is a staple in design museums.

But since the sharpener doesn't move it's absurd to shape it this way. It's a kind of postmodernism - the form and function are juxtaposed!

7. Papanek famously, and comically, railed against this:

"In any reasonably conducted home, alarm clocks seldom travel through the air at speeds approaching five hundred miles per hour - streamlining clocks is out of place."

"In any reasonably conducted home, alarm clocks seldom travel through the air at speeds approaching five hundred miles per hour - streamlining clocks is out of place."

8. But who can say?

Design for function and design for aesthetic pleasure are both important, just for different reasons.

If the clock works well, and has a shape you enjoy regardless of how absurd, who's to argue? Style preference is part of human nature.

Design for function and design for aesthetic pleasure are both important, just for different reasons.

If the clock works well, and has a shape you enjoy regardless of how absurd, who's to argue? Style preference is part of human nature.

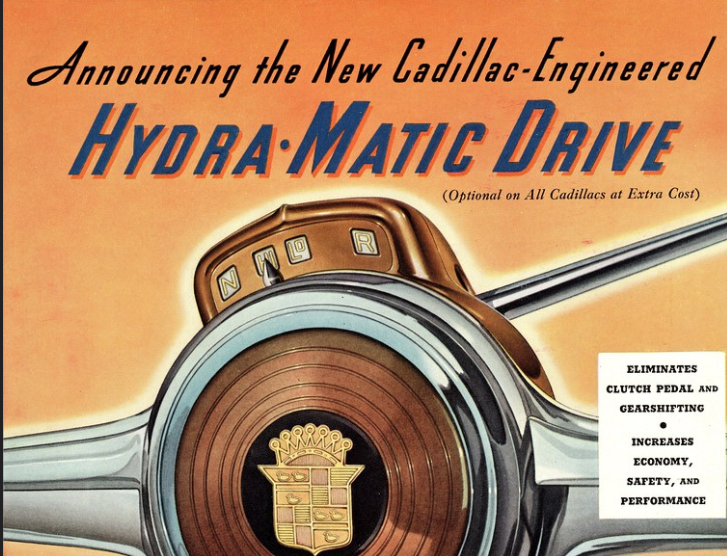

9. The way products are marketed today, from high style phone bezels to "Hyrda-mattic" like feature additions, has its roots back in the Great Depression and with Sloan at GM.

If you're a designer of most kinds, this is the history that explains your profession today.

If you're a designer of most kinds, this is the history that explains your profession today.

10. If you liked this thread, most of if it comes from my new book, How Design Makes The World.

You can read the first chapters here - check it out. Thx.

bit.ly/hdmw-excerpt #design #designmtw #ux

You can read the first chapters here - check it out. Thx.

bit.ly/hdmw-excerpt #design #designmtw #ux

Source of that first statistic on design employment:

Manufacturing: Design, Production, Automation, and Integration, by Beno Benhabib, pg. 44

Manufacturing: Design, Production, Automation, and Integration, by Beno Benhabib, pg. 44

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh