MINI-THREAD: #Biblical #Chronology, the #Seder #Olam, and the #LXX.

TITLE: Too long in #Lockdown.

SUB-TITLE: ...although at least I now have multiple ways to calculate how long I’ve been here...

TITLE: Too long in #Lockdown.

SUB-TITLE: ...although at least I now have multiple ways to calculate how long I’ve been here...

I’m presently working my way through the Seder Olam--a 2nd cent. AD (or so I’m told) Rabbinic text which deals with the chronology of Scripture.

I highly recommend it.

Below is an interesting phenomen I’ve observed.

I highly recommend it.

Below is an interesting phenomen I’ve observed.

The author (Rabbi Yose) likes to ‘back out’ (i.e., infer) absent numbers from long-term measurements of time.

Or at least that’s how it looks to me.

Or at least that’s how it looks to me.

For instance, R. Yose arrives at a figure of 28 years for the reign/judgeship of Joshua,

but doesn’t tell us how he arrives at it.

As best as I can tell, Yose’s logic is as follows.

but doesn’t tell us how he arrives at it.

As best as I can tell, Yose’s logic is as follows.

Premise 1: Year statements at the end of episodes in Judges state the overall length of those episodes.

For instance, at the end of Judges 3, the phrase ותשקט הארץ שמונים שנה = (trad.) ‘and the land had rest for 80 years’...

...means, ותשקט הארץ. בסך הכל היו שמונים שנה = ‘and the land had rest. In total, there were 80 years’.

...means, ותשקט הארץ. בסך הכל היו שמונים שנה = ‘and the land had rest. In total, there were 80 years’.

(I’m not sure how that would be written in classical Hebrew. Maybe ראש שנה שמונים? Suggestions welcome.)

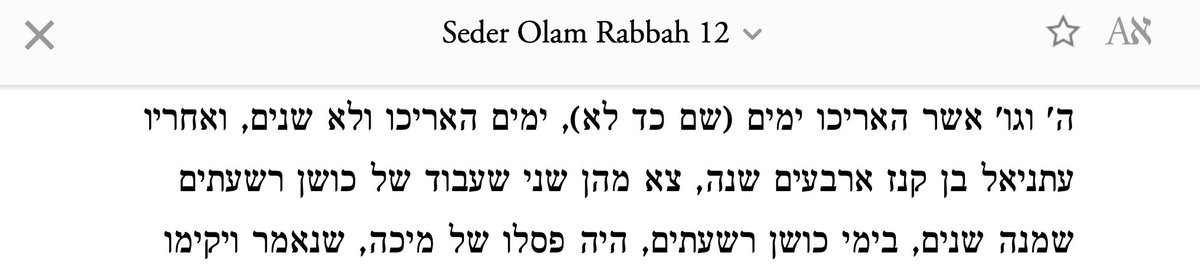

Hence, for instance, R. Yose writes, ‘After (Othniel’s rest), Ehud ben Gera had 80 years. To be excluded from them are the years in which he was in servitude (to) Eglon, the king of Moab: 18 years’:

All well and good (one might say).

Premise 2: Measurements of time are to be understood literally and exactly.

Premise 2: Measurements of time are to be understood literally and exactly.

Specifically, if Jephthah says the Israelites have inhabited Canaan for 300 years (when he speaks to the Ammonites), then the Israelites must have inhabited Canaan for exactly 300 years at that time.

(I’m sure someone once told me #literalism was a modern notion.)

(I’m sure someone once told me #literalism was a modern notion.)

Premise 3: When the book of Judges lists a series of judges, their judgeships can be assumed to share a year in common, which should be subtracted from long-run year-counts. See below for an example:

Conclusion: Joshua must have reigned for 28 years since...

...Othniel’s 40 years + Ehud’s 80 + Deborah’s 40 + Midian’s 7 + Gideon’s 40 + Abimelech’s 3 + Tola’s 23 + Jair’s 22 - 1 year shared in common by Tola and Jair + the Ammonites’ 18 years...

...Othniel’s 40 years + Ehud’s 80 + Deborah’s 40 + Midian’s 7 + Gideon’s 40 + Abimelech’s 3 + Tola’s 23 + Jair’s 22 - 1 year shared in common by Tola and Jair + the Ammonites’ 18 years...

...comes to a total of 272 years,

in which case Joshua must have judged Israel for 28 years.

Fine (one might say).

In light of R. Yose’s (apparent) logic, a number of questions arise.

in which case Joshua must have judged Israel for 28 years.

Fine (one might say).

In light of R. Yose’s (apparent) logic, a number of questions arise.

First: if, as I’m often told, round numbers aren’t viewed as exact measurements in ancient ‘Jewish thought’ (?)--e.g., if ‘forty years’ = ‘a long time’, ‘eighty years’ = ‘a longer time’, etc.--, then why does R. Yose expect series of numbers to add up?

And why does he think absent numbers can be inferred on the basis of such arithmetic?

Second: might certain chronological calculations in the NT employ a similar logic?

Paul says ‘about 450 years’ passed between the entrance into Canaan and the rise of ‘Samuel the prophet’ (Acts 13.20).

Paul says ‘about 450 years’ passed between the entrance into Canaan and the rise of ‘Samuel the prophet’ (Acts 13.20).

Paul’s statement has caused chronologers a lot of headaches.

And chronologers have enough headaches as it is, so it would be nice if some of them could be removed.

So here’s a potentially helpful suggestion.

And chronologers have enough headaches as it is, so it would be nice if some of them could be removed.

So here’s a potentially helpful suggestion.

Maybe Paul has calculated his 450 years in a similar way to Rabbi Yose, but has interpreted the ‘end of episode’ statements in Judges differently.

The year totals listed in the book of Judges come to a total of 410 years.

See, for instance, Chisholm’s paper:

The year totals listed in the book of Judges come to a total of 410 years.

See, for instance, Chisholm’s paper:

And Eli’s judgeship lasts for 40 years (1 Sam. 4).

Maybe, therefore, Paul gets from the entrance to Canaan to the rise of Samuel in 450 years simply by adding together all the intervals mentioned in Judges plus Eli’s judgeship.

Maybe, therefore, Paul gets from the entrance to Canaan to the rise of Samuel in 450 years simply by adding together all the intervals mentioned in Judges plus Eli’s judgeship.

Of course, Paul would have known there would have been gaps between some of the intervals he’d added up (and overlaps between others).

But he could still have added them up to obtain a total which was ‘about’ right.

But he could still have added them up to obtain a total which was ‘about’ right.

Third, Eugene Merrill has written a paper on Paul’s reference to 450 years.

If, in these days of increased availability, it’s available somewhere, could someone please let me know?

THE END.

If, in these days of increased availability, it’s available somewhere, could someone please let me know?

THE END.

P.S. Oops, didn’t get round to the #LXX stuff. Maybe next time.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh