I do not like the mortgage interest deduction, and I especially do not like it at the higher end of the housing price distribution.

jec.senate.gov/public/index.c…

It's not so much that the owner/renter distinction is important for this in itself, but owner-occupied homes are more likely to have extra bedrooms to give to kids.

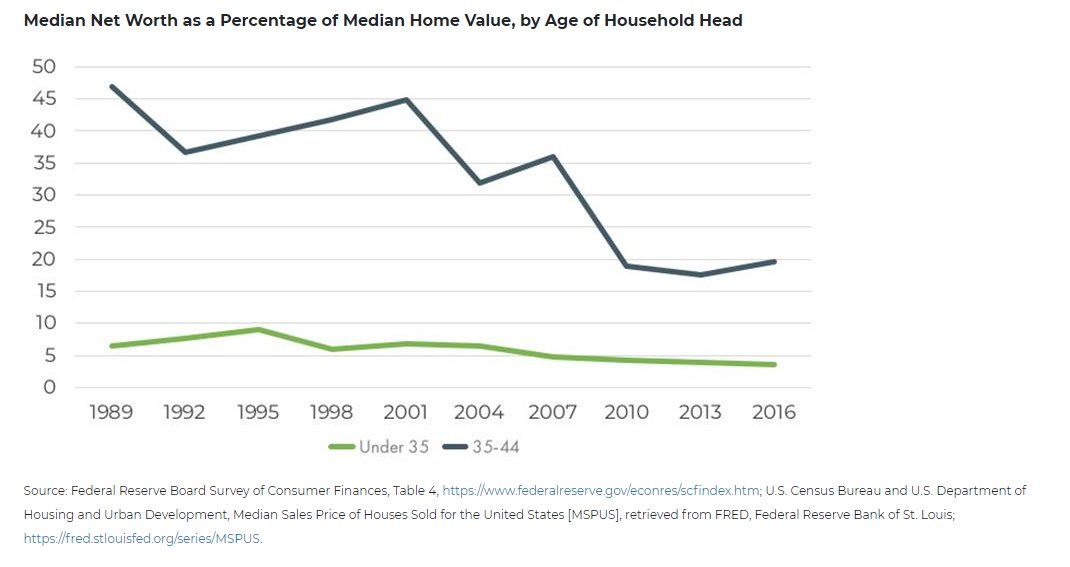

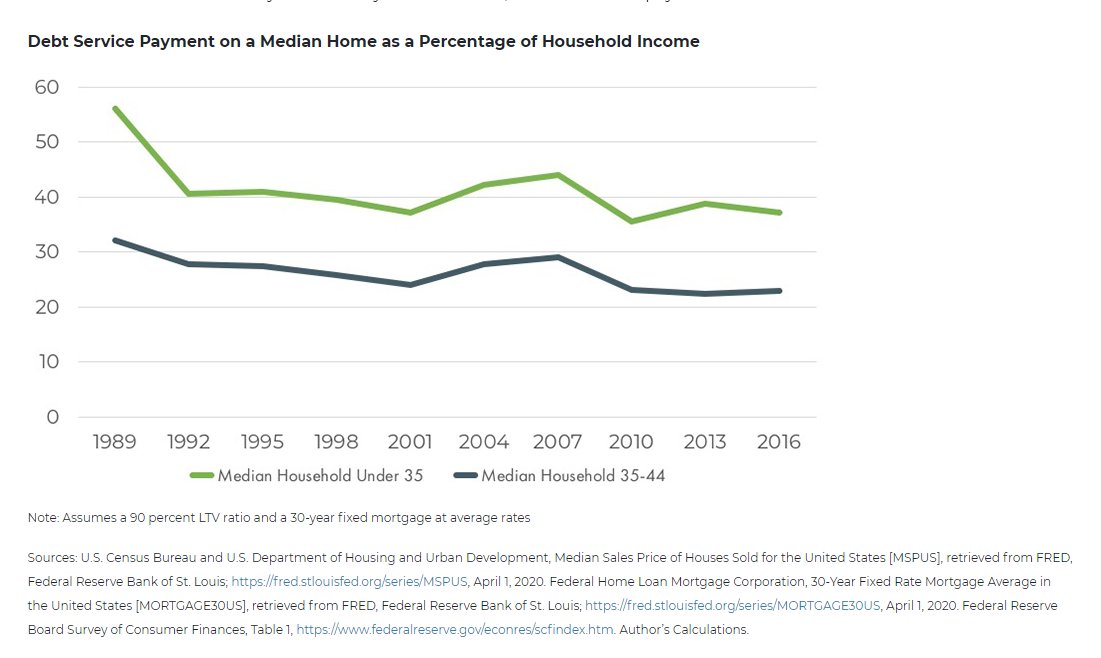

The up-front cost you pay with existing wealth; the monthly installments, with future income.

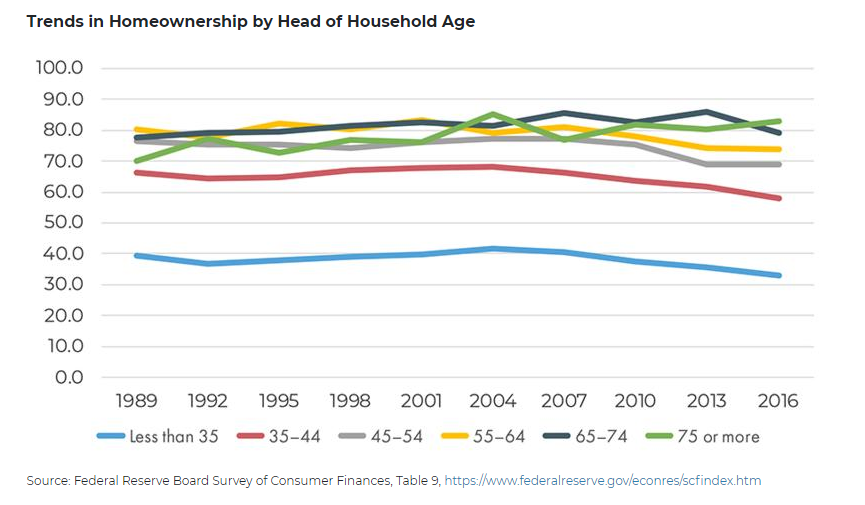

How have people's abilities to pay each of these changed over time?

At best, this is mistargeted help: on the easier part, not the tough part.

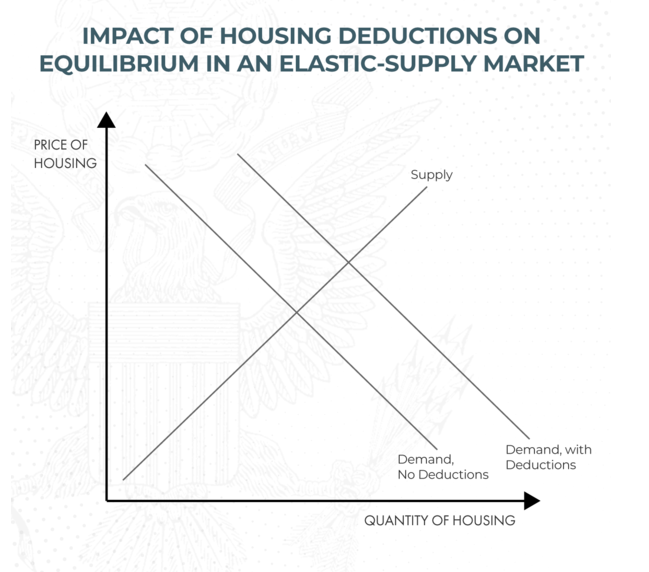

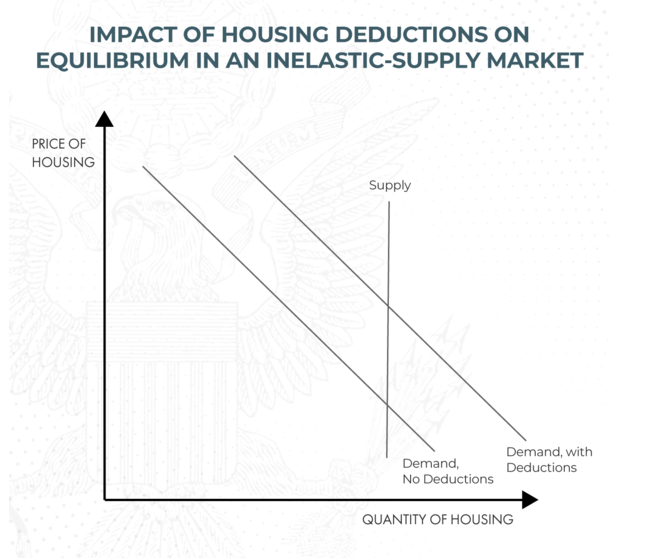

(There's some math for this in a theoretical model, but common sense works too. Of course you'll pay more if the purchase gets you some tax deductions.)

henrikkleven.com/uploads/3/7/3/…

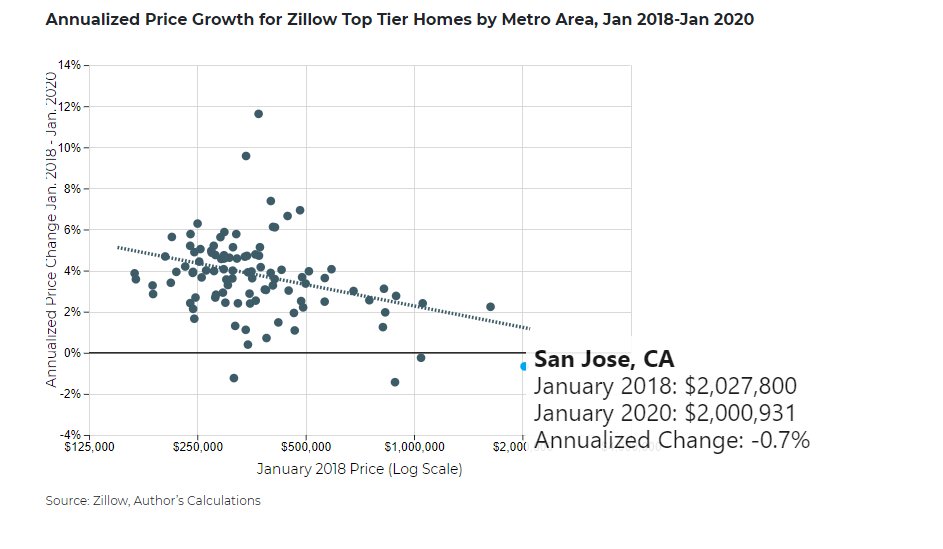

It limited housing tax deductions at the high end of the distribution. (For example, mortgage interest deductibility beyond 750k of principal.)

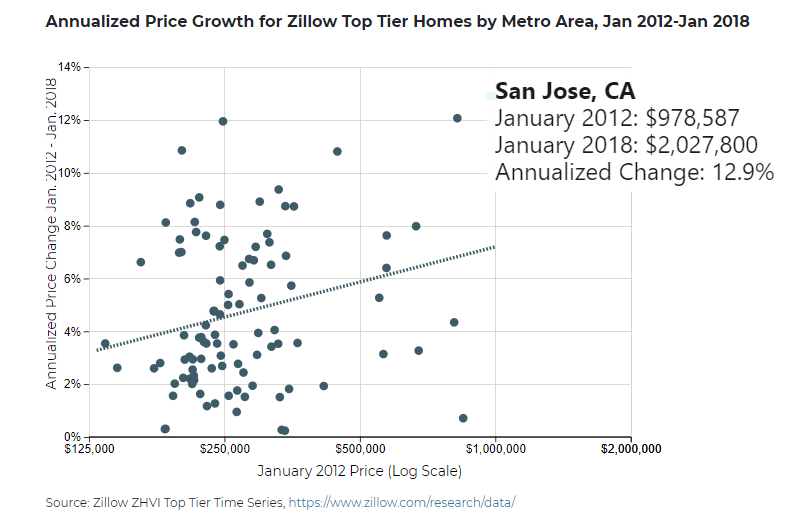

To mouse over this plot and look at interesting cities, go here: jec.senate.gov/public/index.c…

(Arguable whether this trend is truly statistically significant or not, but I'm just establishing a baseline of what the pre-TCJA world looked like.)

After 2018, the whole trend reversed. The expensive markets really cooled down on price, and the affordable markets had their day in the sun.

Once again, find the mouseover ability on the website, here:

jec.senate.gov/public/index.c…

The argument is this: the MID for >$750,000 of principal was largely capitalized into the value of existing homes in San Jose, NYC, and so on. It "passed through" to the incumbent high-end homeowners there.

Also: I don't usually make strong distributional arguments but if you are a homeowner in San Jose you're doing pretty OK.

Housing tax deductions are often couched in the language of family affordability by proponents.

Empirically, though, they don't seem to help, and may even hurt.

There are many proposals that fit this description in one way or another, and I'm not picky between them. They're all good.