When the first white settlers arrived in Montana, the native Salish people warned them to not settle the West side of the Bitterroot River.

Ignoring these warnings, a small group of people colonized that side of the river.

Three quarters-75%-died of a mysterious disease.

Ignoring these warnings, a small group of people colonized that side of the river.

Three quarters-75%-died of a mysterious disease.

The Bitterroot river carves out a 75 mile canyon in Western Montana.

It's not deep at all, averaging only about 3 feet. Animals and humans cross it very easily, and it's not really a barrier to any kind of travel.

The Salish believed evil spirits lived in the area.

It's not deep at all, averaging only about 3 feet. Animals and humans cross it very easily, and it's not really a barrier to any kind of travel.

The Salish believed evil spirits lived in the area.

Saint Mary's mission, founded in 1841, was the first permanent European settlement in Montana.

The European settlers weren't very nice to the natives, and the poor relationship caused the mission to close.

The European settlers weren't very nice to the natives, and the poor relationship caused the mission to close.

A trading post which mostly serviced trappers, Fort Owen, popped up about 10 years later.

When the owner, John Owen discovered gold in the area, this set off a gold rush in the area.

Unfortunately, the disease on the West side of the bitterroot river made life difficult.

When the owner, John Owen discovered gold in the area, this set off a gold rush in the area.

Unfortunately, the disease on the West side of the bitterroot river made life difficult.

Not much was known about this disease until the early 1800s, when the state board of health brought in Louis Wilson and William Chowning to investigate.

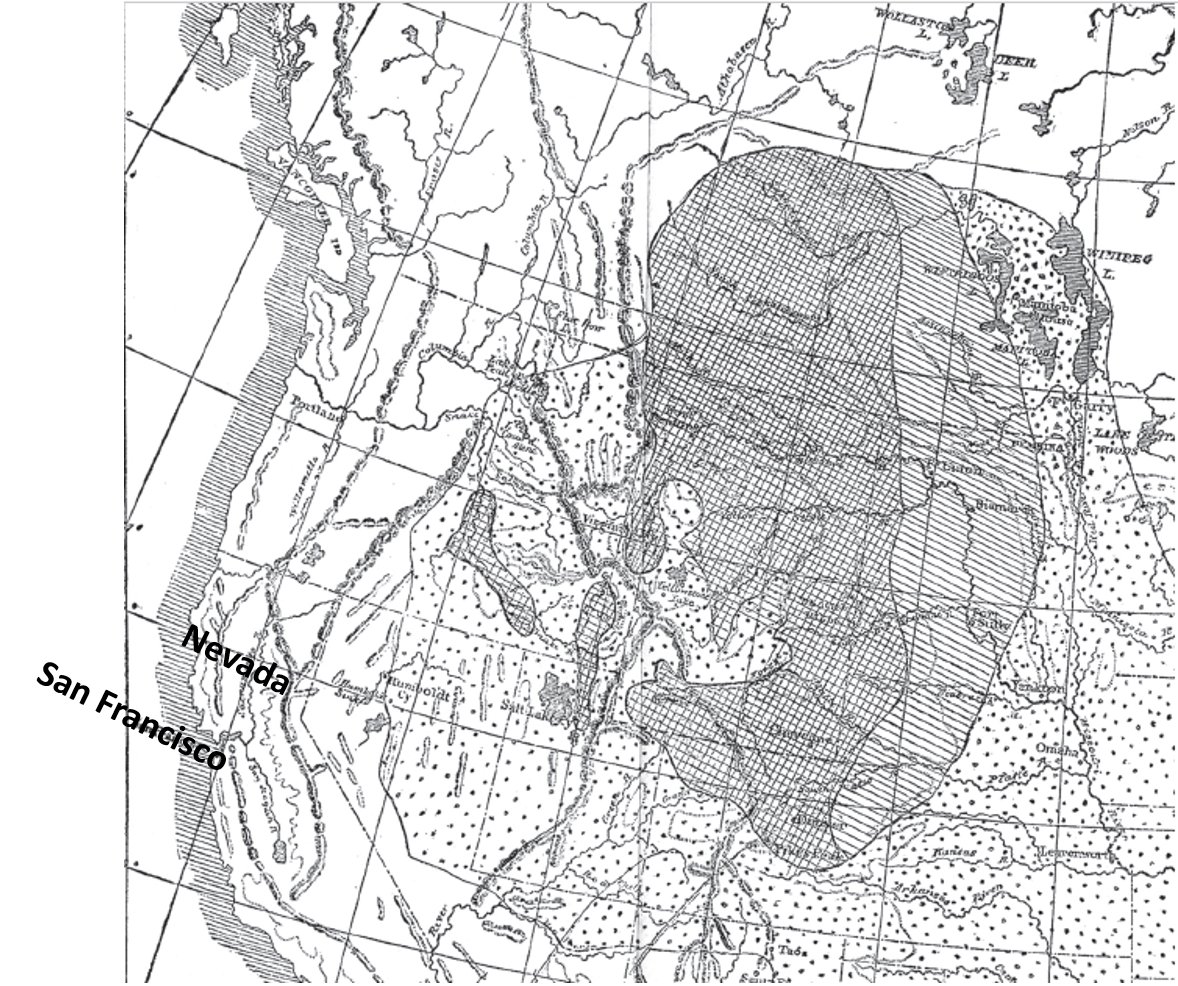

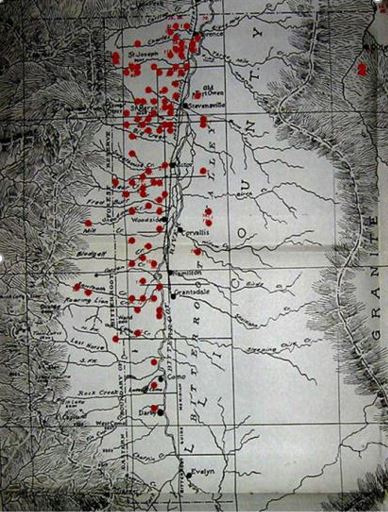

They did a lot of research on the disease, eventually creating the map below

They did a lot of research on the disease, eventually creating the map below

At the same time, a few other doctors were sent to investigate along with Williams and Chowning.

Together they found out:

It was caught in springtime

It was caught outdoors

The Salish rarely got the disease

Together they found out:

It was caught in springtime

It was caught outdoors

The Salish rarely got the disease

The more these early researchers found out about it, the more mysterious it became.

People became really sore, and developed a fever. A rash of purple spots dotted the body. Some would go blind or deaf. Loss of balance was pretty common.

It didn't appear to be contagious.

People became really sore, and developed a fever. A rash of purple spots dotted the body. Some would go blind or deaf. Loss of balance was pretty common.

It didn't appear to be contagious.

The disease remained mysterious, until two doctors L.P. Macalla and H.A. Bereton had a patient who was bitten by a tick.

One which looked a lot like the one below.

That patient later developed the symptoms described in the post above.

One which looked a lot like the one below.

That patient later developed the symptoms described in the post above.

So they took the tick, and allowed it to bite another healthy person.

They got the disease.

So they fed a tick on that person, and THAT person got the disease as well.

Unfortunately, they didn't publish these results until much later.

They got the disease.

So they fed a tick on that person, and THAT person got the disease as well.

Unfortunately, they didn't publish these results until much later.

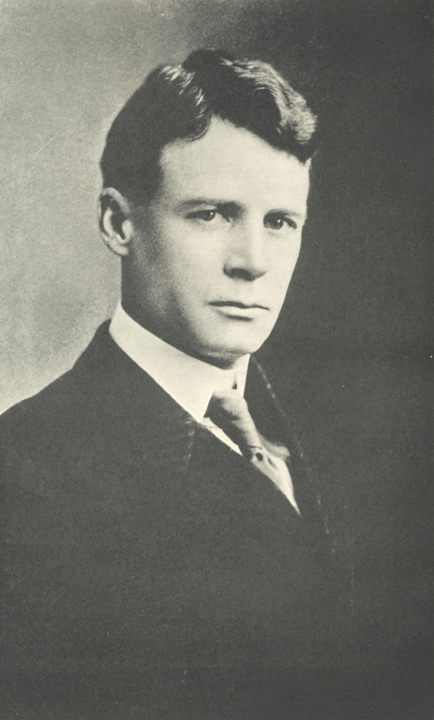

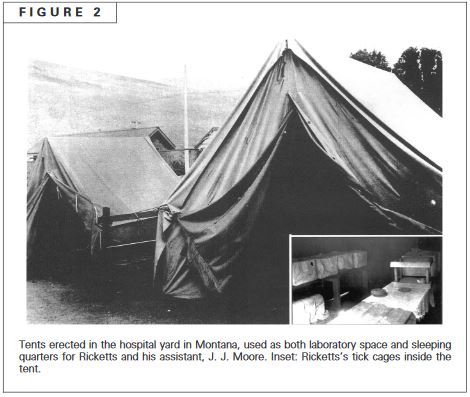

At the same time as this was going on, a young microbiologist by the name of Howard Taylor Ricketts set up shop in the area.

With few laboratory supplies-all of his experiments were done in a tent-he began to look for the cause of this perplexing disease.

With few laboratory supplies-all of his experiments were done in a tent-he began to look for the cause of this perplexing disease.

It didn't take too long before he met a local family living in black measles territory. Their son, William, 10 years old, had caught the disease.

When Ricketts came to visit he found...ticks.

Lots of ticks. Everyone in the family had been bitten by them.

When Ricketts came to visit he found...ticks.

Lots of ticks. Everyone in the family had been bitten by them.

So he drew blood from William Langdon, stained it with a chemical called Eosin, and found bacteria.

He dissected ticks in the area, found the bacteria.

He also found that he could pass the disease among guinea pigs.

He also found bacteria in tick eggs.

web.archive.org/web/2011072223…

He dissected ticks in the area, found the bacteria.

He also found that he could pass the disease among guinea pigs.

He also found bacteria in tick eggs.

web.archive.org/web/2011072223…

He named this bacteria after himself, Rickettsia rickettsii.

The disease would go on to be well studied, and go by a few other names. However, over time, the scientific community settled on a name originally published in 1903.

Rocky Mountian Spotted Fever

The disease would go on to be well studied, and go by a few other names. However, over time, the scientific community settled on a name originally published in 1903.

Rocky Mountian Spotted Fever

The story of this disease is one I've wanted to tell for awhile, and by no means does it end here.

The story of RMSF is a really important cautionary tale for why people like us, those who specialize in outreach, are so important.

The story of RMSF is a really important cautionary tale for why people like us, those who specialize in outreach, are so important.

In addition, the Bitterroot strain of RMSF has remained a biological mystery that has baffled scientists to this day.

So, next week, I'll be talking about part 2:

The legal war over Rocky Mountian Spotted Fever

So, next week, I'll be talking about part 2:

The legal war over Rocky Mountian Spotted Fever

Also, on our Deep Dives, we're absolutely terrible at acknowledging our sources and we need to work on this.

Here are the sources we consulted if you want to read more:

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/P…

wemjournal.org/article/S1080-…

jstor.org/stable/pdf/414…

jstor.org/stable/4147077…

Here are the sources we consulted if you want to read more:

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/P…

wemjournal.org/article/S1080-…

jstor.org/stable/pdf/414…

jstor.org/stable/4147077…

jstor.org/stable/pdf/301…

Armstrong, M. (2017). Germ Wars: The Politics of Microbes and America's Landscape of Fear (Vol. 2). Univ of California Press.

Armstrong, M. (2017). Germ Wars: The Politics of Microbes and America's Landscape of Fear (Vol. 2). Univ of California Press.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh