In 1875, a series of locust swarms the size of California ripped through the Western frontier

Blotting out the sun and causing the modern equivalent of $4 billion in damages, major famines followed in their wake

In 1902, just 25 years later, the species went extinct

#DeepDive

Blotting out the sun and causing the modern equivalent of $4 billion in damages, major famines followed in their wake

In 1902, just 25 years later, the species went extinct

#DeepDive

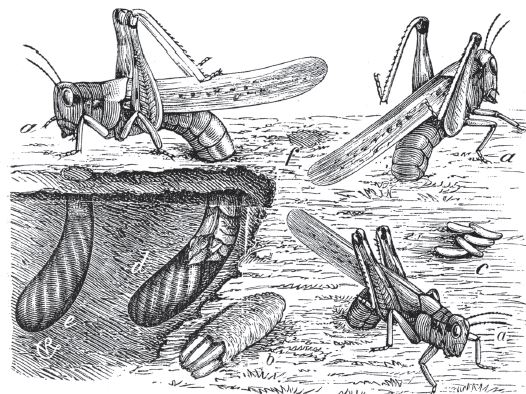

The grasshopper, the Rocky Mountian locust, was once the most numerous animal on the planet.

So numerous, that entomologists didn't bother to collect them.

The only specimens came from a glacier in Montana, which has since melted b/c global warming

formontana.net/grasshopper.ht…

So numerous, that entomologists didn't bother to collect them.

The only specimens came from a glacier in Montana, which has since melted b/c global warming

formontana.net/grasshopper.ht…

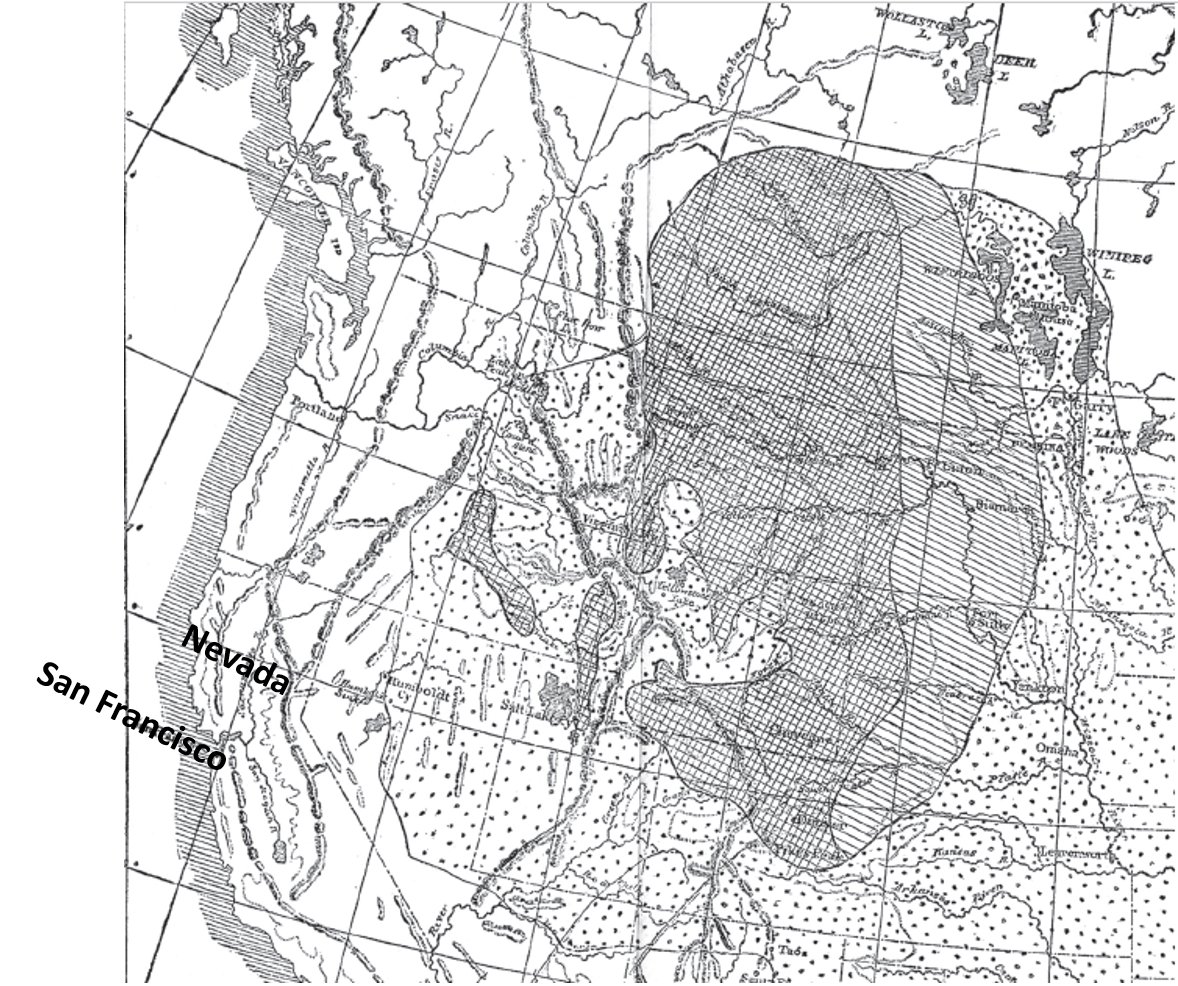

The Rocky Mountain Locust, Melanoplus spreta, once had a range which covered almost the entirety of the US.

It was a highly mobile species which had been collected from Nevada all the way to St. Louis.

It bred mostly in the Rocky Mountain river basin.

It was a highly mobile species which had been collected from Nevada all the way to St. Louis.

It bred mostly in the Rocky Mountain river basin.

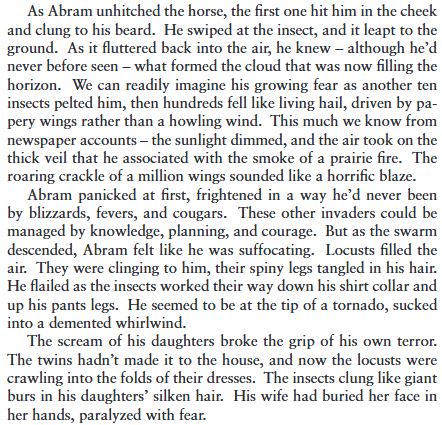

Despite how important the insect was there's virtually nothing known about its biology

We don't know what conditions caused it to swarm, and the question of whether it was even a real species was only answered in 2004

Well, kind of. Maybe. Complicated

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

We don't know what conditions caused it to swarm, and the question of whether it was even a real species was only answered in 2004

Well, kind of. Maybe. Complicated

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

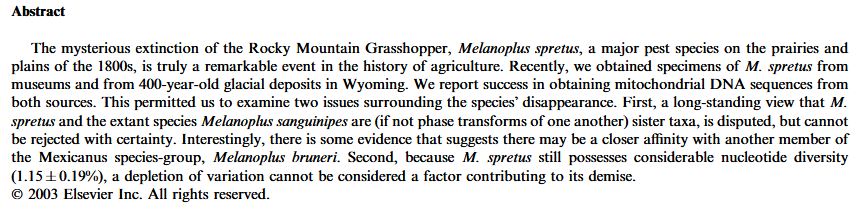

Much of what we know about how this species interacted with people came from diaries from the 1800s.

The descriptions of the 1875 swarm are bone-chilling, even to the most seasoned of entomologists.

watermark.silverchair.com/ae50-0224.pdf?…

The descriptions of the 1875 swarm are bone-chilling, even to the most seasoned of entomologists.

watermark.silverchair.com/ae50-0224.pdf?…

Locust swarms in the 1800s were a hurricane of insects which ate everything in sight

If you're a subsistence farmer, you REALLY need your crops.

If they're eaten by bugs, you aren't going to have food for the winter.

If you're a subsistence farmer, you REALLY need your crops.

If they're eaten by bugs, you aren't going to have food for the winter.

The 1875 swarm, named Albert's swarm, was intensively studied by entomologists.

The most valuable information, however, came from someone who wasn't even an amateur entomologist.

Albert Child was an amateur meteorologist!

The most valuable information, however, came from someone who wasn't even an amateur entomologist.

Albert Child was an amateur meteorologist!

Albert Child was educated as a doctor, and served in the US Army. After leaving the army, he became a school superintendent.

Soon after, he discovered a love of farming and moved to Nebraska.

He had an interest in meteorology, and kept meticulous records about the weather

Soon after, he discovered a love of farming and moved to Nebraska.

He had an interest in meteorology, and kept meticulous records about the weather

When the 1875 swarm hit Nebraska, Child's first instinct was to do the impossible. He wanted to measure the swarm.

He used the swarm's speed to measure the width, and a telescope to measure the height.

His measurements:

1,800 miles long

110 miles wide

1/3rd miles high

He used the swarm's speed to measure the width, and a telescope to measure the height.

His measurements:

1,800 miles long

110 miles wide

1/3rd miles high

There is no way to know how many individual insects were in the swarm.

Conservative estimates are in the tens of trillions. The likely number is in the hundreds of trillions.

So, how and WHY, did these insects go extinct?

Well, it comes down to their habitat and biology.

Conservative estimates are in the tens of trillions. The likely number is in the hundreds of trillions.

So, how and WHY, did these insects go extinct?

Well, it comes down to their habitat and biology.

While they were widespread, that's only because they were able and willing to fly long distances.

They mostly bred in the river basins of the rocky mountians.

Unlike most grasshoppers, their eggs weren't buried deeply, and suffocated easily if flooded.

They mostly bred in the river basins of the rocky mountians.

Unlike most grasshoppers, their eggs weren't buried deeply, and suffocated easily if flooded.

As agriculture overtook The West, many of their egg cases were trampled by livestock and smashed by ploughs.

Beavers nearly went extinct, disrupting dams and flooding breeding grounds.

Wolves and cougars were over-hunted, causing overgrazing of food supplies at the same time.

Beavers nearly went extinct, disrupting dams and flooding breeding grounds.

Wolves and cougars were over-hunted, causing overgrazing of food supplies at the same time.

The Rocky Mountain Locust only had a few breeding grounds, but they were connected by the high mobility of the species.

As fewer locusts survived, the breeding grounds went unused and they were out-competed.

As fewer locusts survived, the breeding grounds went unused and they were out-competed.

It could have survived any one of these assaults, but the combination of all of them was just too much.

The last verified specimen was collected in 1902, and the Rocky Mountain locust was officially declared extinct in 2014.

No living entomologist has seen a live specimen.

The last verified specimen was collected in 1902, and the Rocky Mountain locust was officially declared extinct in 2014.

No living entomologist has seen a live specimen.

Since 1902, the species has become somewhat of a "cryptid".

Sporadic reports come in (we've even received a report via @Stylopidae's DMs), but none have ever been verified.

While it's always possible that a non-migratory form exists, there's no evidence to support this.

Sporadic reports come in (we've even received a report via @Stylopidae's DMs), but none have ever been verified.

While it's always possible that a non-migratory form exists, there's no evidence to support this.

We always think that these animals are immune to extinction, but there's a lot of parallels between the Rocky Mountian locust, the periodical cicada, and even the Monarch butterfly.

Each one of these animals, the cicadas, the Monarch, and the Rocky Mountain Locust, exist in huge numbers but can only breed in relatively small habitats.

The Rocky Mountain locust existed in much higher numbers than either of these.

The Rocky Mountain locust existed in much higher numbers than either of these.

"Death by a thousand cuts" is the idea that many small things can interact to cause extinction, even if one thing wasn't enough to cause extinction.

When we talk about insect declines, the Rocky Mountain locust is our cautionary tale.

When we talk about insect declines, the Rocky Mountain locust is our cautionary tale.

Sources:

Lockwood, J. A. (2009). Locust: the devastating rise and mysterious disappearance of the insect that shaped the American frontier. Basic Books.

Riley, C. V. (1877). The rocky mountain locust. The American Naturalist, 11(11), 663-673.

Lockwood, J. A. (2009). Locust: the devastating rise and mysterious disappearance of the insect that shaped the American frontier. Basic Books.

Riley, C. V. (1877). The rocky mountain locust. The American Naturalist, 11(11), 663-673.

Lockwood, J. R. (2010). The fate of the Rocky Mountain locust, Melanoplus spretus Walsh: implications for conservation biology. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews, 3(2), 129-160.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh