A few quick and dirty #CPSMicrodataDay charts, as I ponder other ones.

According to the household survey, broad labor market disruption fell by 8 million people in May, but there are still 32 million people who have left jobs or had their hours involuntarily cut since February. /1

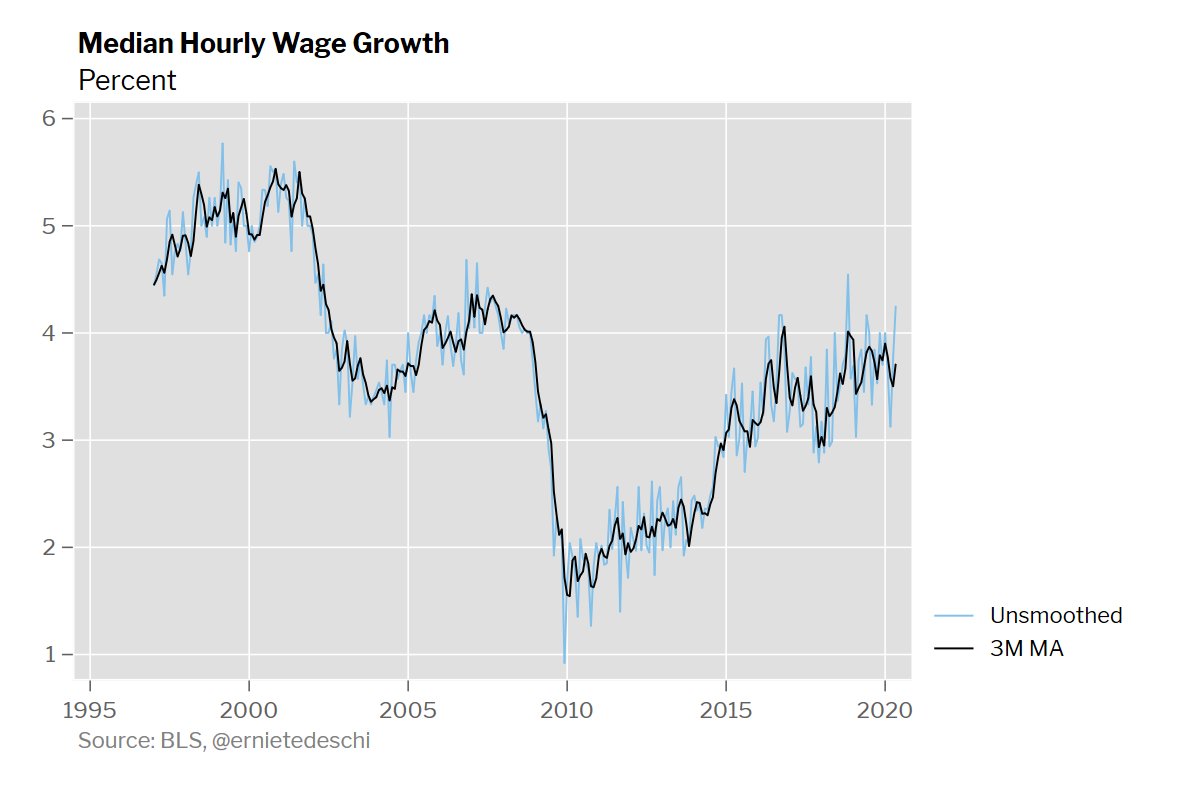

We need to be very cautious about CPS data right now, but one interesting result: median same-worker wage growth hasn't slowed significantly yet, either on an hourly or weekly basis.

That's not what we would expect in such a sharp downturn, though perhaps this takes time. /2

That's not what we would expect in such a sharp downturn, though perhaps this takes time. /2

That said, non-raise rates are rising, though note this series is noisy and the 12-month moving average I use will necessarily only change slowly. /3

But--and this is why we need to be more cautious these days--response rates are plunging, widening the uncertainty bands around the data. /4

Moreover, in-person interviews are plunging too (for utterly defensible reasons!), but in-person interviews consistently yield higher unemployment rates for some reason, so this shift may be having a compositional effect on the CPS, though I'm sure BLS has tried to adjust. /FIN

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh