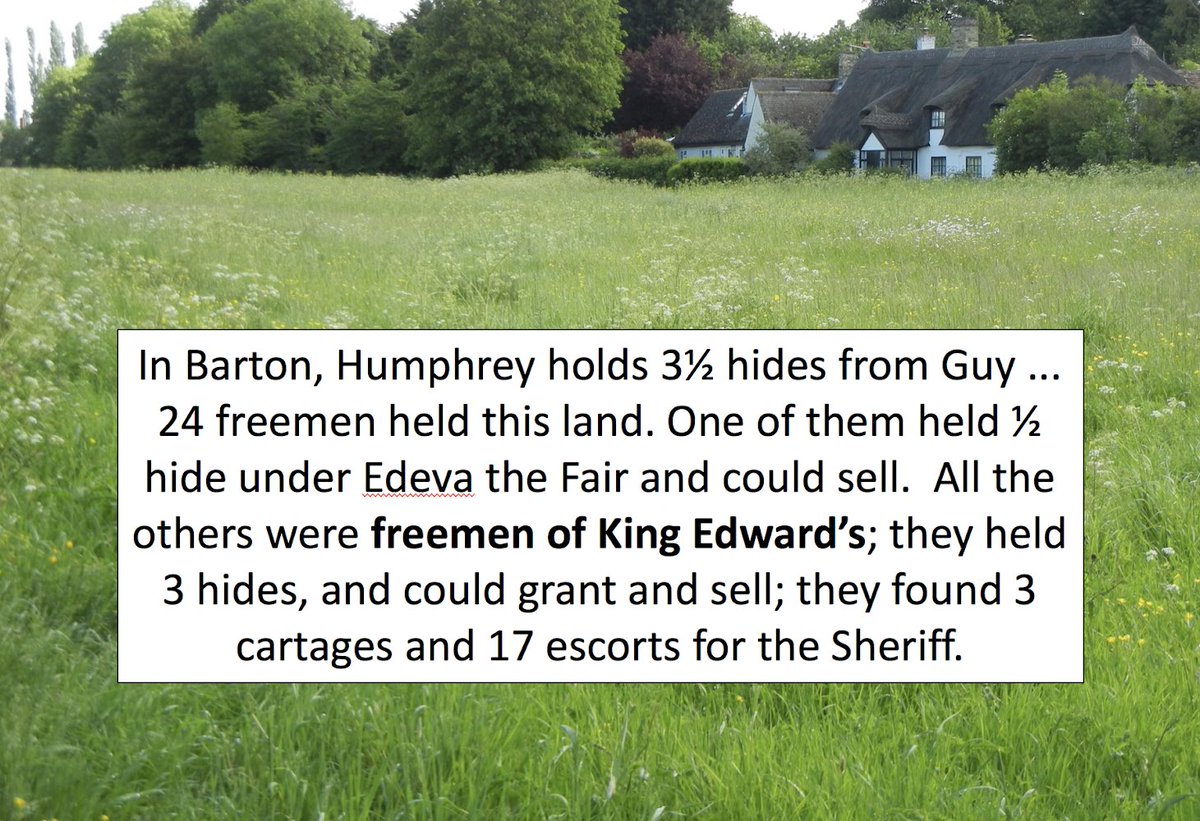

THREAD. This entry is typical of the Cambs. #Domesday Book (1086).

1st, it lists the major landowners after the Norman Conquest - here at Barton, Humphrey was Guy de Raimbeaucourt’s tenant in 1086.

2nd (& this is what I’m interested in) it lists the landowners *before* ...

1st, it lists the major landowners after the Norman Conquest - here at Barton, Humphrey was Guy de Raimbeaucourt’s tenant in 1086.

2nd (& this is what I’m interested in) it lists the landowners *before* ...

2. ... 1066. As you can see, there were 24 of them & they were all free men - they could grant and sell their land without permission from anyone else. They didn’t ‘belong’ to a manor, but farmed independently.

And DB tells us a number of other interesting things about them ...

And DB tells us a number of other interesting things about them ...

3. They were commended to the king for patronage and protection, & in return performed specific services for him - in this case they carted his goods, people, crops, etc.from one place to another, & they provided a mounted escort for the Sheriff when he undertook official duties.

4. Why is this interesting. Well, it’s because this form of relationship & service appears to have already been ancient by the 11thC. Dr Rosamond Faith has argued that they may have originated in the 5th/6thC organisation of early medieval territories. How did that work?

5. (Pauses to find an image)

6. Well, (be patient with me) Faith argues that property rights in land came with free status within each territory - however wealthy/poor, powerful/weak, high/low status one was, if that you were free then once you were adult you were entitled to rights of property. AND ...

7. those property rights were made up of 2 complementary bundles:

(1) rights in what was later called ‘severalty’ = enough land to farm on your own account to support your extended household, &

(2) shared rights to exploit the territory’s non-arable resources, eg woods & pasture

(1) rights in what was later called ‘severalty’ = enough land to farm on your own account to support your extended household, &

(2) shared rights to exploit the territory’s non-arable resources, eg woods & pasture

(8. For more detail on commons see

https://twitter.com/drsueoosthuizen/status/1160205043716493312?s=21) https://t.co/cJeWLrzlYs

9. But, as the saying goes, those rights brought responsibilities with them - & these are the responsibilities still visible in many Cambs. landholdings just before the Norman Conquest. They were archaic by then - the framework within which they originate had long since been ...

10. ... replaced by the organisation structures of the manor. Yet, in Cambs., there appears to have been a substantial class of men in 1065/6 who were not obligated to any manor. Why had these kinds of holdings survived?

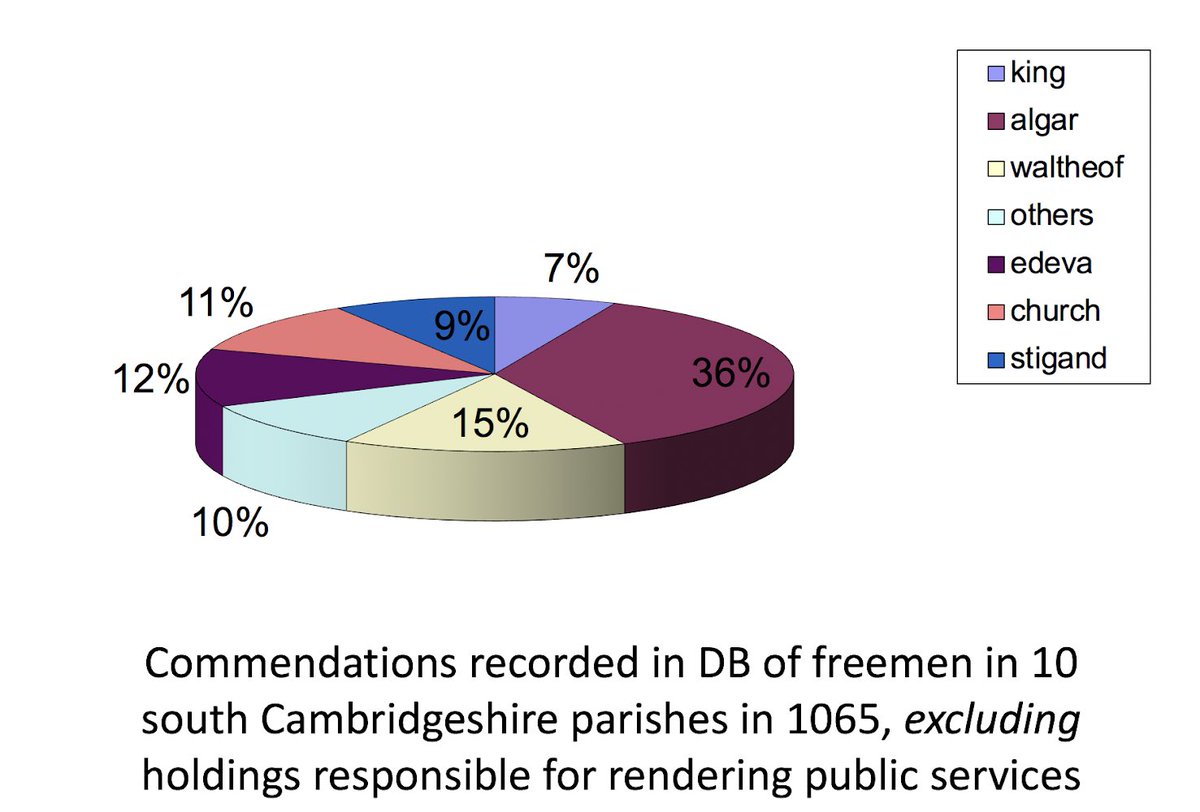

11. The answer may appear by comparing commendations by freemen whose holdings didn’t owe any public responsibilities ...

12. .. with those freemen whose holdings did come with those public responsibilities - around half of whom were commended to the king.

13. This appears to be the key to their survival - public responsibilities brought status and a personal connection with the royal court. And the importance to 11thC Cambs. freemen of these relationships can also be discerned in DB ..

14. Look at the size of their holdings. 23 men held 3 hides. A hide was a NOTIONAL area, varying from one place to another, which could provide the same output as one might expect to make from 120 acres. In theory, then, our 23 men held 360 acres between don’t know if

15. their holdings were all the same size or varied wildly. On average (which may be an assumption too far) they each held about 15 acres - perhaps just to be responble for these public duties. (I suspect most of them had other holdings, too, which didn’t carry public duties.)

16. And the extraordinary thing is that these archaic holdings *still* survived across the medieval fenland into the mid-13thC - because of the status they carried with them: their holders were required to attend the hundred court, to accompany the sheriff.

17. There is something extraordinarily touching in the persistence of such ancient traditions among small landowners from the formation of early medieval territories, through the formation of kingdoms & the evolution & formalisation of manors, into & beyond the Norman Conquest.

18. Again, a bit niche, but I love it all the same. 🤗

There’s more about the DB freemen in Ch. 6 of Landscapes Decoded (downloadable at …ofsusanoosthuizen.files.wordpress.com/2020/01/oosthu…) & more on the 13thC fen holdings on pp. 19-23 of The Anglo-Saxon Fenland (not yet freely available, I’m afraid). END

There’s more about the DB freemen in Ch. 6 of Landscapes Decoded (downloadable at …ofsusanoosthuizen.files.wordpress.com/2020/01/oosthu…) & more on the 13thC fen holdings on pp. 19-23 of The Anglo-Saxon Fenland (not yet freely available, I’m afraid). END

Apologies: that darned spellchecker again: the last sentence should read ‘our 23 men held 360 acres between them’. Mostly I catch that blasted imp but sometimes I just get too absorbed to check it #blush

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh