And it becomes all the more remarkable when we consider:

a] its numerical properties, and

b] its Babylonian background.

a] Daniel’s trio of attributes (‘light, insight, and wisdom’: 5.11, 14),

b] Daniel’s threefold ability (‘the ability to interpret dreams, explain riddles, and solve problems’: 5.12), and

which is mentioned three times (5.7, 16, 29).

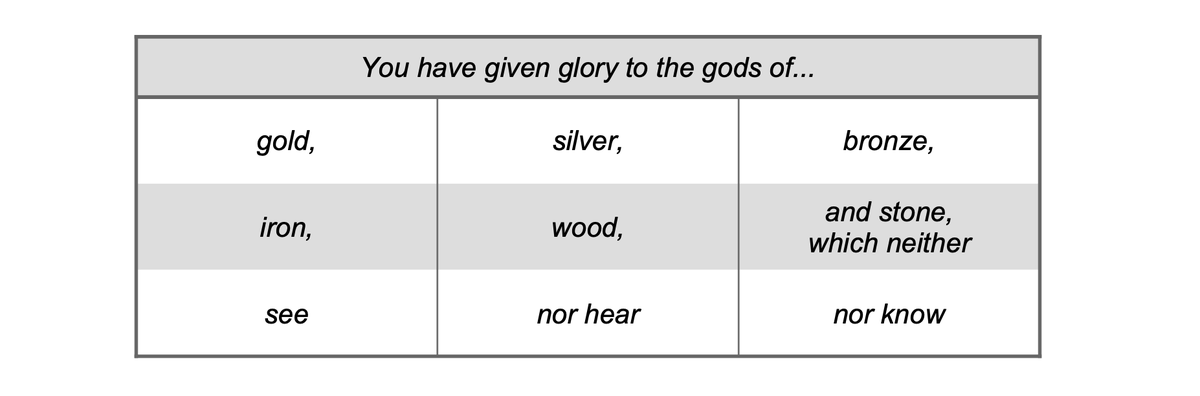

As the party warms up, Belshazzar decides it might be a good idea to involve God’s vessels in his debauchery.

Suffice it to say, it is not a good idea.

but they clearly declare an important message.

And Belshazzar’s inability to decipher the characters on his wall makes them seem all the more ominous.

First of all he summons Babylon’s wise men and instructs them to read the characters.

Babylon’s wise men, however, are unequal to the task,

which will prove to be their third and final failure in the book of Daniel.

who is not his favourite wise man (for various reasons, which will soon become clear).

He knows the person who wrote them.

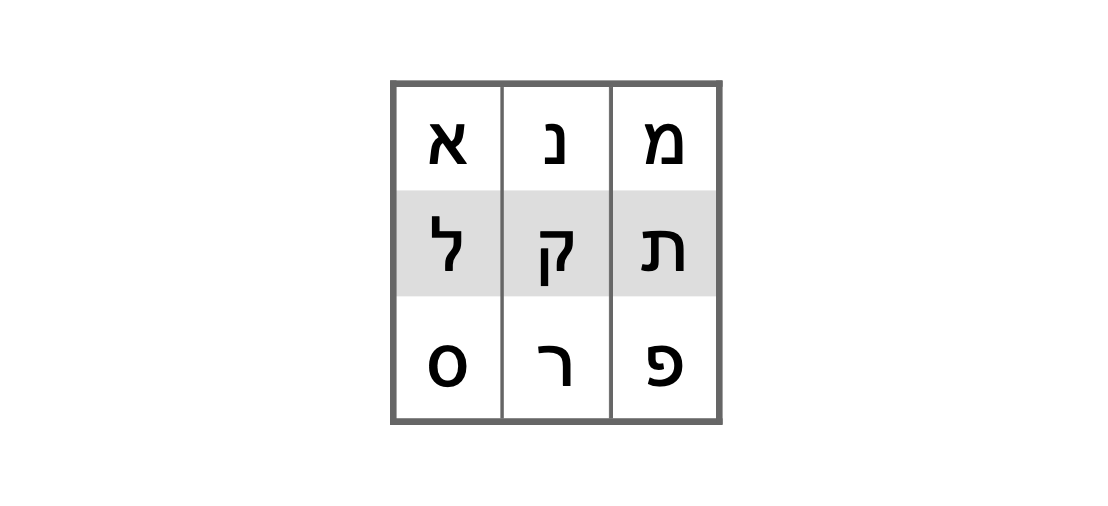

Daniel hence reads the letters out to the hushed multitude in a loud and clear voice:

‘Meneh’, ‘Meneh’, ‘Tekel’, and ‘Parsin’. (‘Parsin’ is the plural of ‘Peres’.)

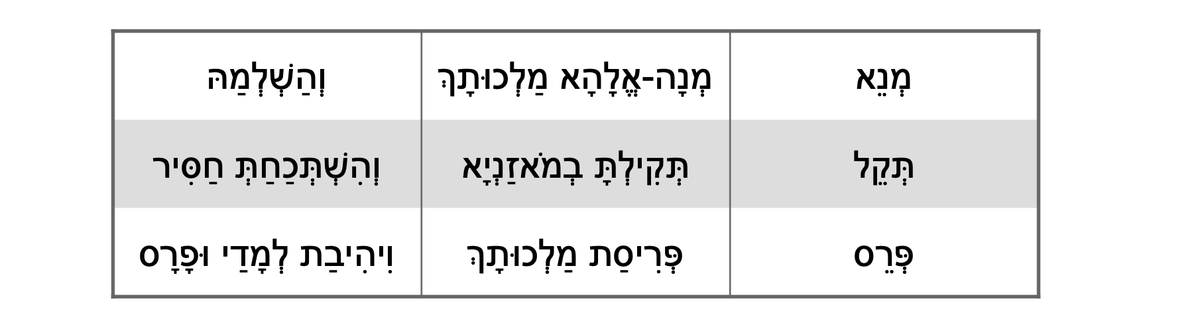

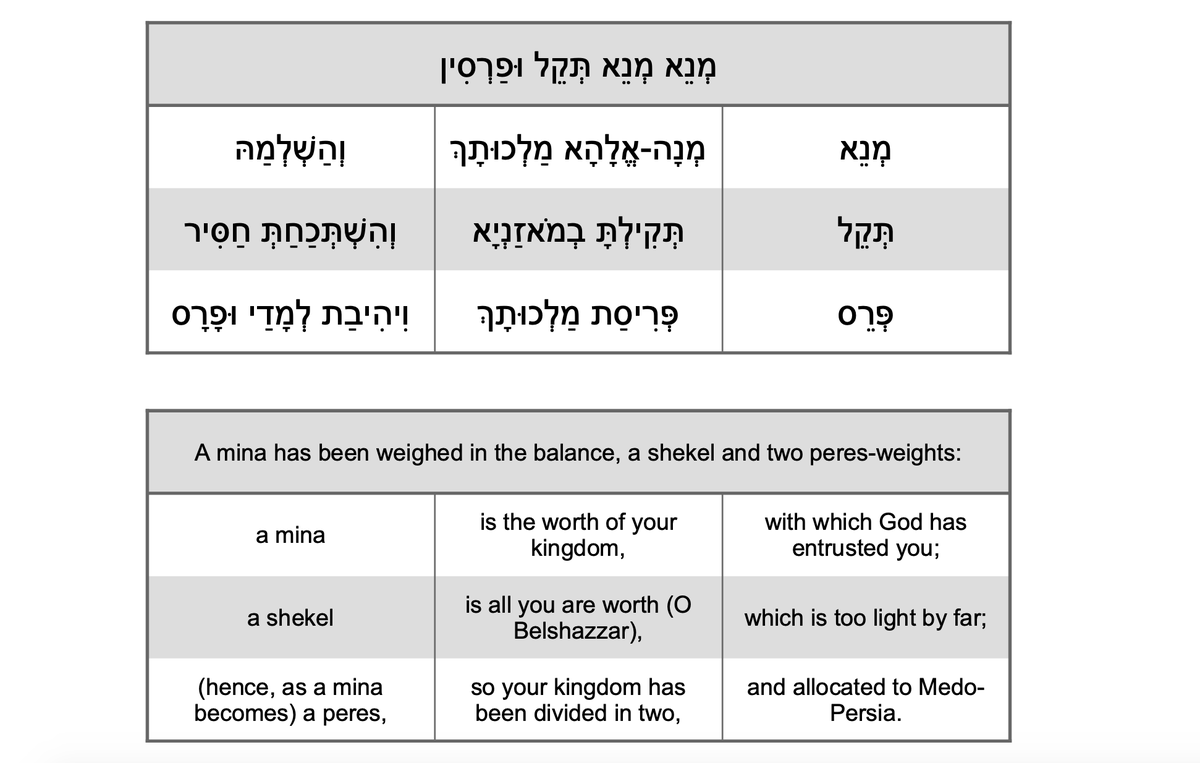

His interpretation consists of three verses,

each of which is composed of three elements:

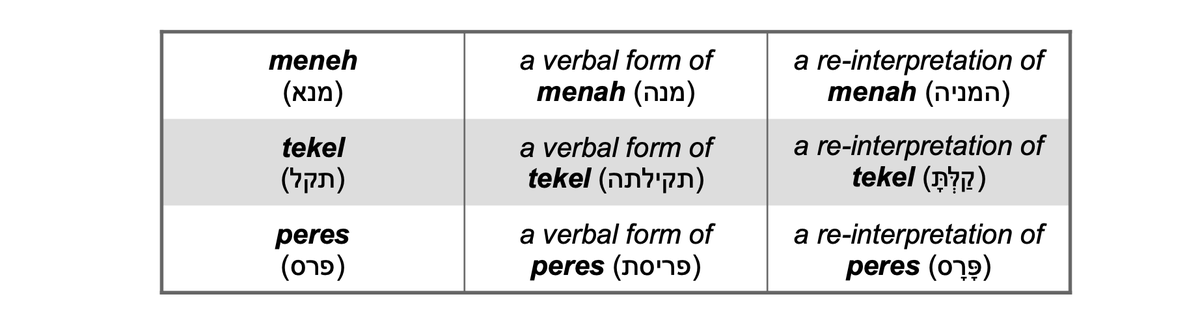

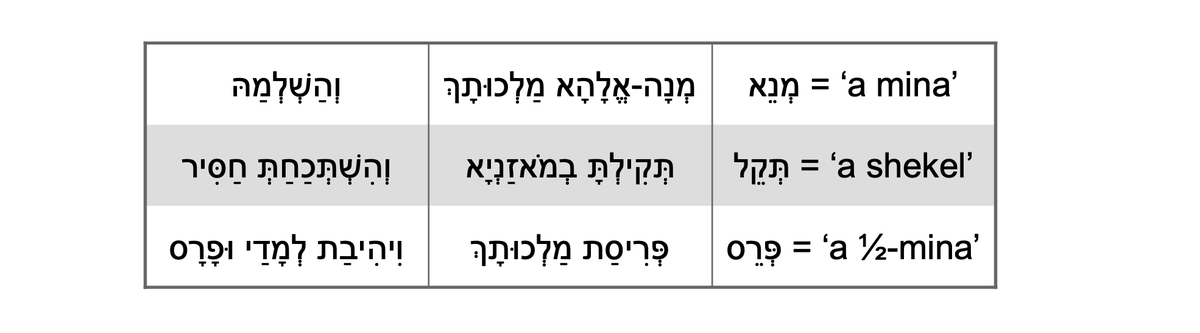

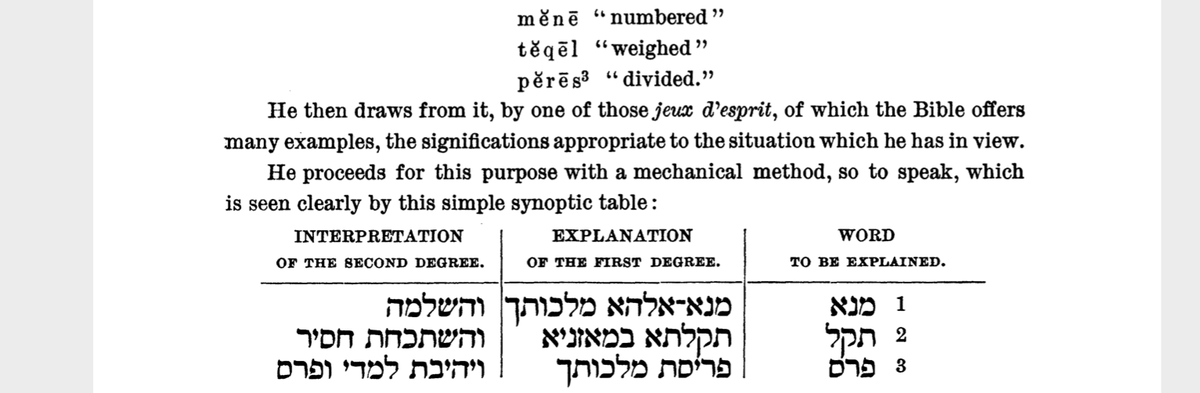

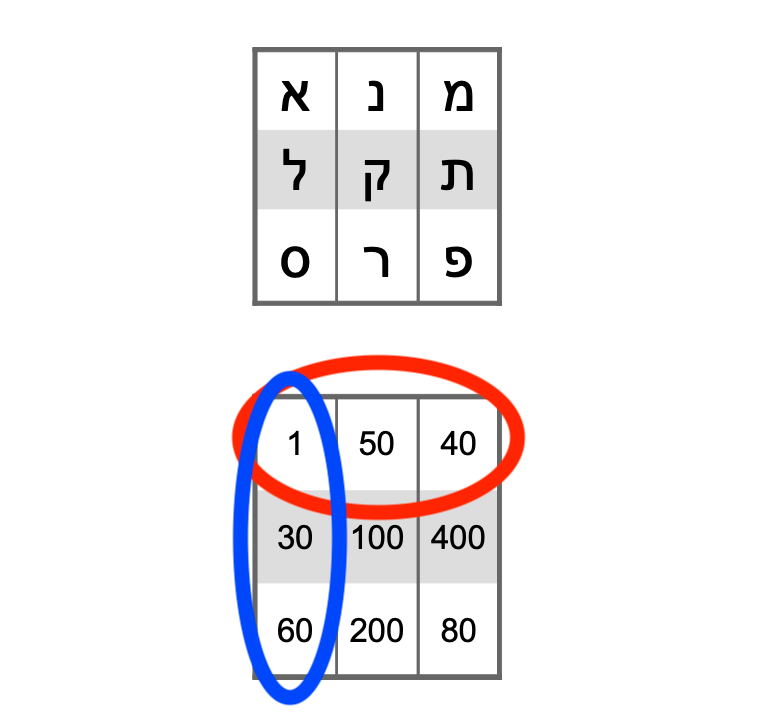

a] one of the words Daniel has just read out (‘Meneh/Tekel/Peres’),

which was typically written without vowels.

We can therefore think of the characters on Belshazzar’s wall in terms of a string of consonants—very roughly,

MNHMNHTQLPRSYN

«MNH», «TQL», and «PRS».

First, Daniel turns these consonants into known Aramaic words by the insertion of (e) vowels:

‘Meneh’ (5.26), ‘Tekel’ (5.27), and ‘Peres’ (5.28).

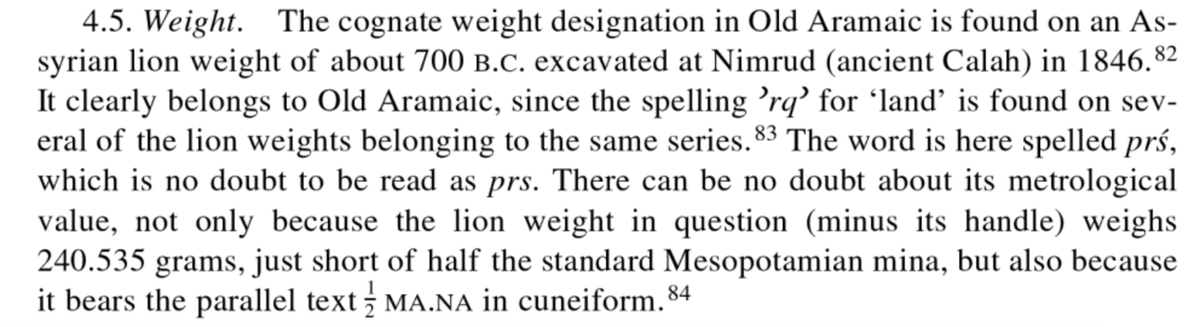

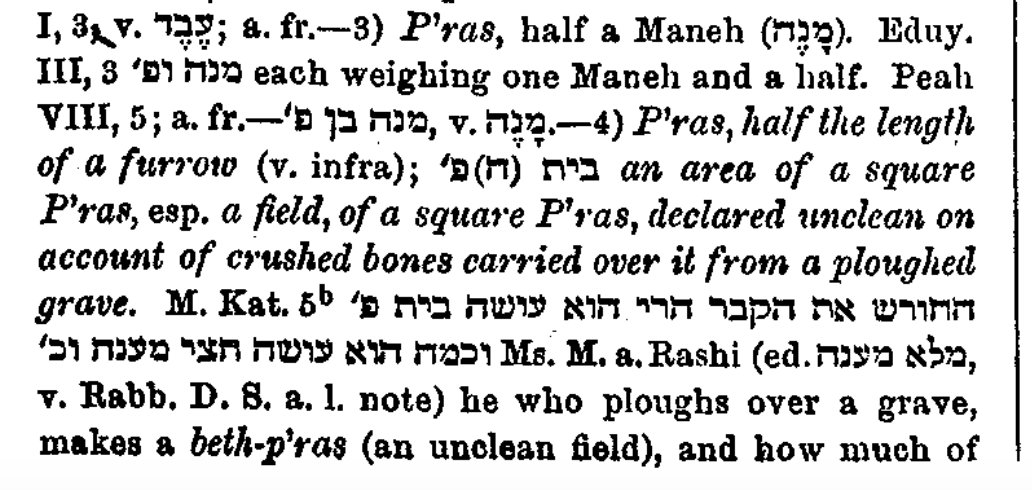

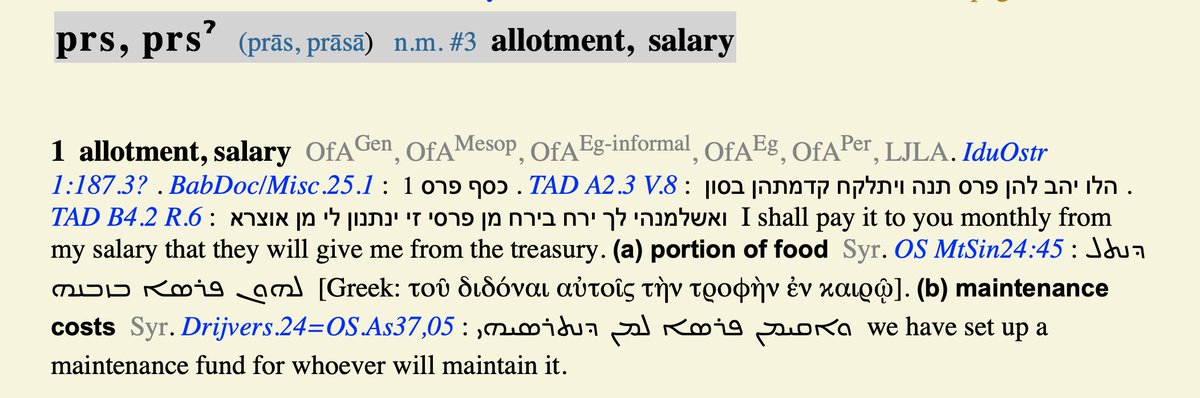

More specifically, he interprets it as a series of nouns which signify *weights*.

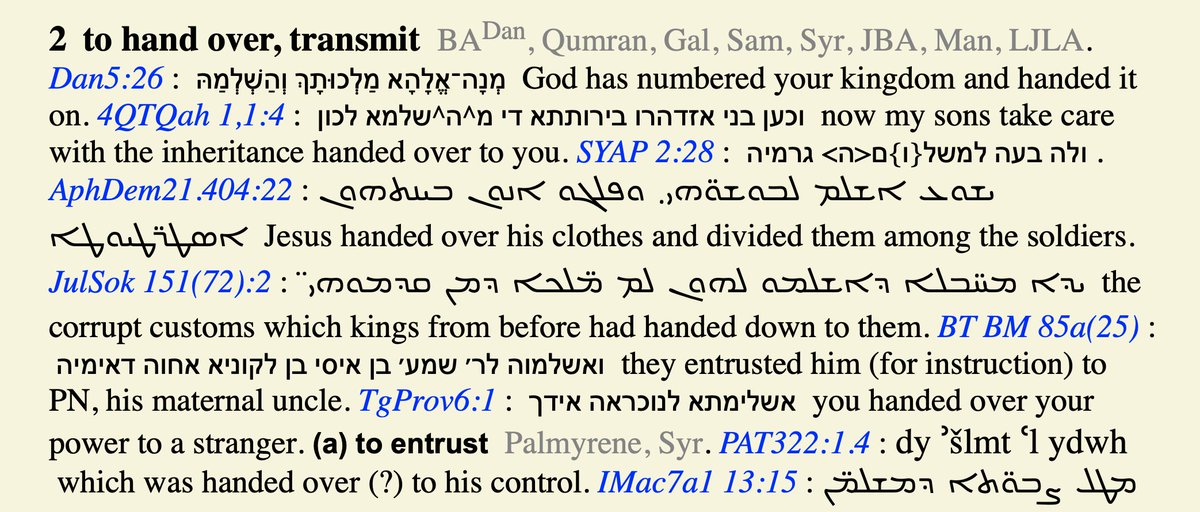

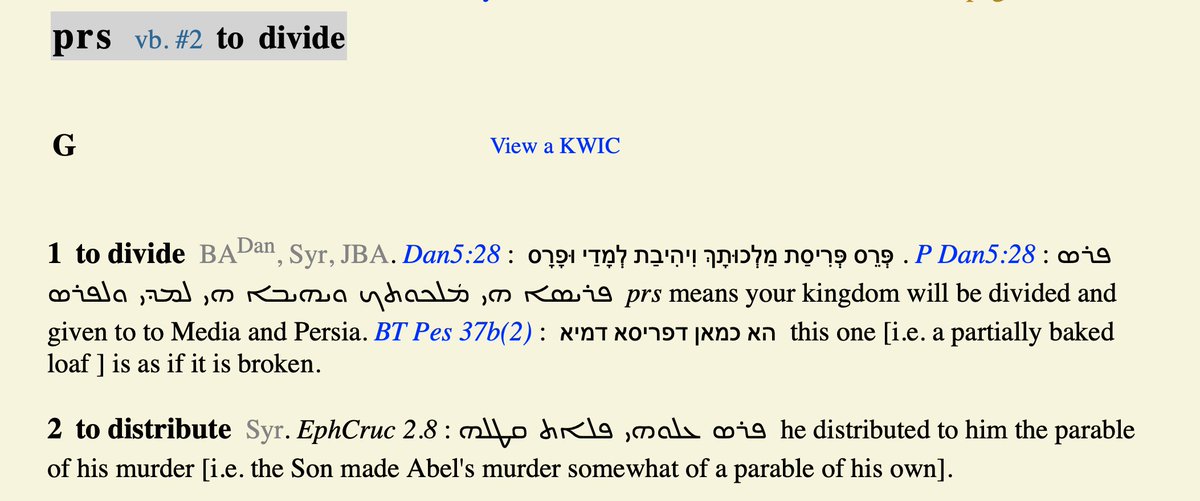

In 5.26–28, Daniel interprets each group of consonants not as a noun, but as a *verb*.

‘teqel’ as a conjugation of «TQL» = ‘to weigh’,

and ‘peres’ as a conjugation of «PRS» = ‘to divide up, distribute’.

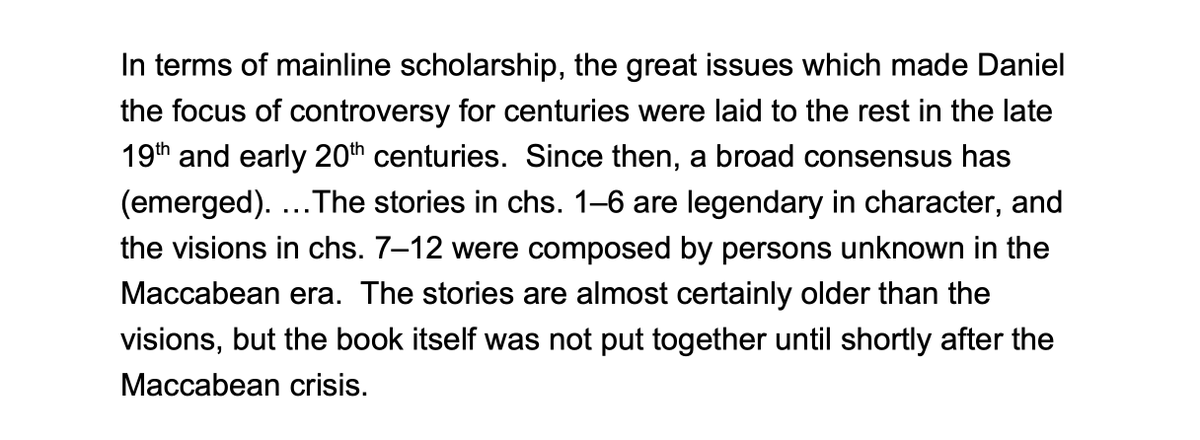

We can, therefore, think of Daniel’s interpretation of the riddle as a 3 x 3 grid,

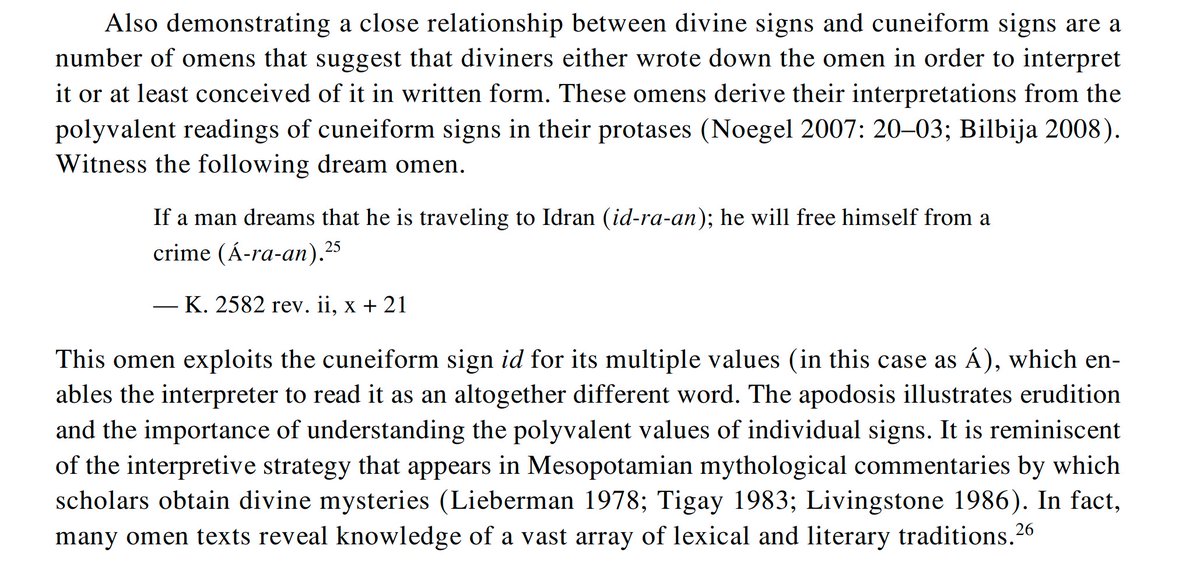

When omens are interpreted in Mesopotamian texts—and an omen is surely what the characters on Belshazzar’s wall are—, it’s not uncommon for interpreters to explore the lexical resources of particular words.

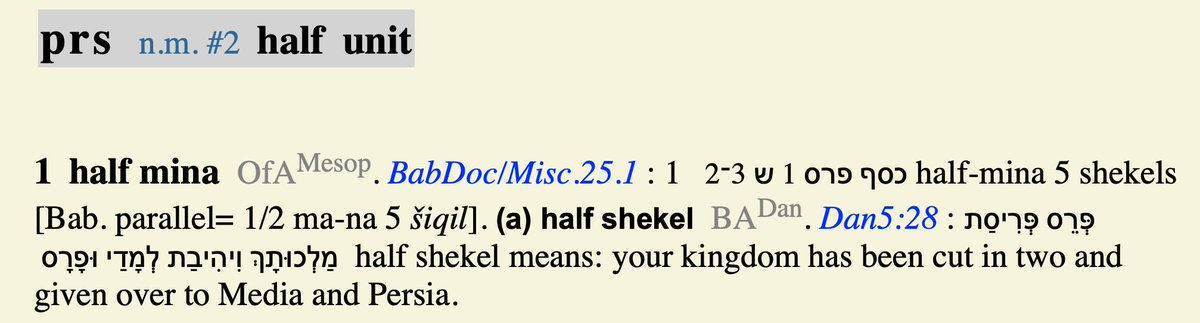

…combined with the revocalisation of ‘peres’ (‘a half mina’) as ‘Paras’ (‘Persia’).

‘A mina has been weighed in the balance, (and) a shekel and two peres-weights (also)’.

In other words, ‘Three weights have been put on the balances’.

I hence take vs. 26 to mean,

‘God has assessed the worth of your kingdom as a mina, and has entrusted it to you’.

To be entrusted with Babylon is, therefore, a grave responsibility.

‘You, (O Belshazzar), a mere shekel, have been weighed in the balances and found wanting!’.

Given its position/status in the ANE, the king of Babylon must be a man of sufficient weight/dignity,

which Belshazzar is not.

God has determined a kind of ‘mina of the land/kingdom’.

He has determined the worth of Babylon and the kind of man required to rule it.

He is too ‘light/contemptible’ a ruler for Babylon.

His kingdom will hence be divvied up and (re)distributed to a twofold empire, viz. Medo-Persia.

The view of Dan. 5.25–28 set out above has a number of points in its favour

It explains why Belshazzar’s riddle (5.25) mentions the particular weights it does:

in 5.26, God states what he requires of Babylon’s ruler—a *sixty-shekel* king;

and, in 5.28, God appoints a new (sixty-shekel) government, which consists of two *thirty-shekel* kingships.

It explains why the king is forced to recognise Daniel’s solution to his riddle as unquestionably correct. (It fits the details perfectly.)

As we’ve noted, Daniel’s solution to the riddle begins with a nine-syllable pronouncement (‘Meneh, Meneh, Teqel, and Parsin’),

which Daniel reduces to a 3 x 3 grid of letters,

Daniel’s solution is also, however, significant in other ways.

a mina = 60 shekels,

a shekel = 1 shekel, and

a half-mina = 30 shekels.

Indeed, the letters in the leftmost column of Daniel’s 3 x 3 grid have the values 1, 60, and 30.

then we end up with a mina, a shekel, and two half-shekels—i.e., 62 shekels—,

(Why would we need to know Darius’s age?)

which curiously anticipates Babylon’s new 121-man government (Darius and his 120 satraps: 6.2).

Hence, for instance, the Mesopotamian deity Anum is referred to as an interpreter (pāšir/mupaššir),

it must, rather, mean ‘one who *dispels/removes* the consequences of dreams’,

especially once the parallel epithet pāšir kišpi = ‘one who removes (evil) magic’ is considered.

...in which Belshazzar rewards Daniel for his announcement of Babylon’s doom.

If so, he hadn’t banked on a simple but important fact.

The word of YHWH’s prophets is very different from the magic and manipulation practiced in Mesopotamia,...

What YHWH says invariably comes to pass.

And it does so in remarkably neat and frequently ironic ways.

THE END.

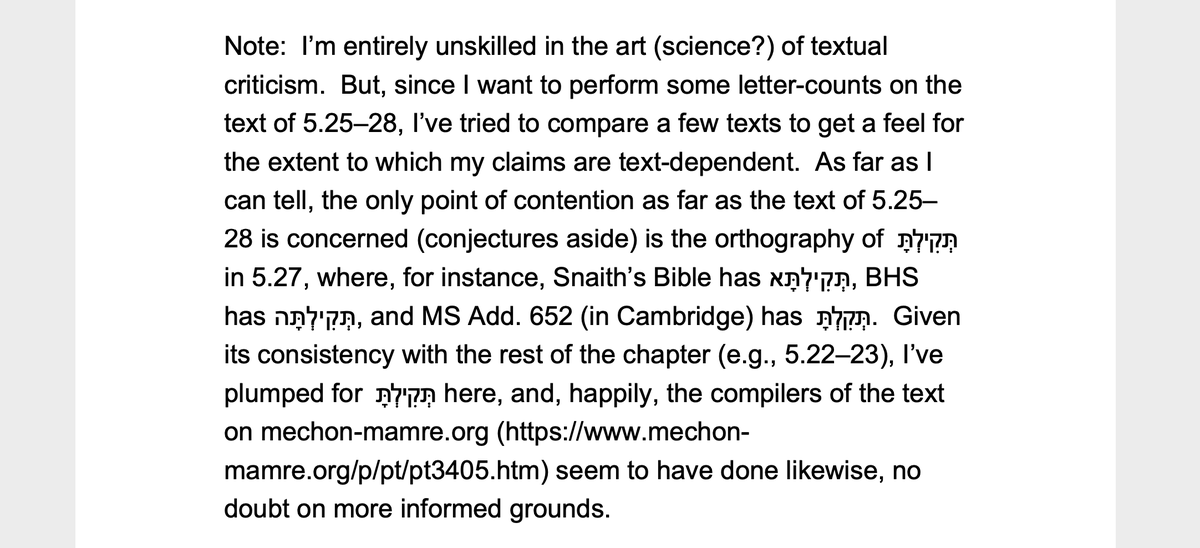

Credits: Al Wolters, 1991. ‘The Riddle of the Scales in Daniel 5’ in HUCA (Vol. 62).