Inventing a #COVID19 vaccine is just a first step. For it to make a material difference in the pandemic, we must also manufacture and distribute it, and people must take it (with confidence that it's safe). Let’s talk about the often-overlooked, unsexy problem of DISTRIBUTION. 1/

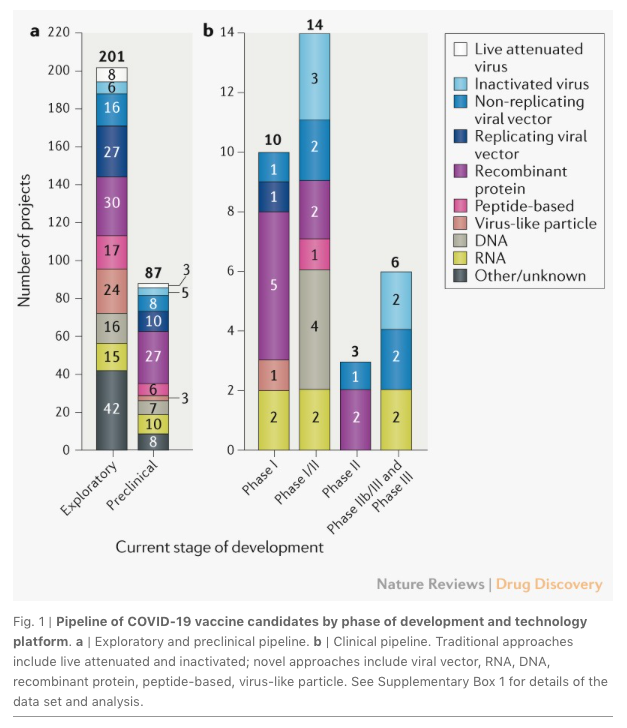

There are many efforts afoot using diverse biological approaches to develop a vaccine. I think it is likely one will be invented – though how safe and effective it will be, and when it will appear, are still far from certain. 2/

As discussed in #APOLLOSARROW, out on October 27 amazon.com/Apollos-Arrow-…, the many steps necessary before widespread vaccination takes place may mean it does not arrive before we reach herd immunity anyway, in 2022 or so. So a vaccine may not materially shorten the pandemic. 3/

On the many vaccine development efforts, see this terrific recent review: nature.com/articles/d4157… 4/

On vaccine manufacturing efforts, note that many pharmaceutical companies, and @BillGates himself (to his great credit), have said they will build factories even before a vaccine is invented. See: businessinsider.com/bill-gates-fac… 5/

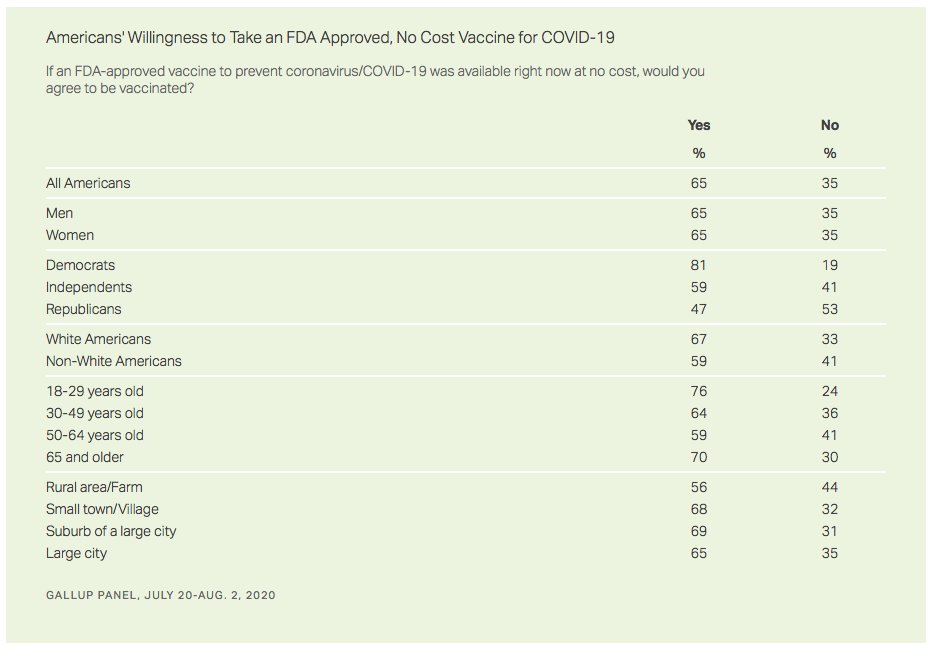

On vaccine acceptance, public interest has fluctuated – with 60-70% saying they would get a shot. See, for example: news.gallup.com/poll/317018/on…

This is not a terrible level for herd immunity, but we would need to actually reach it, and reach it fast, and the higher the better. 6/

This is not a terrible level for herd immunity, but we would need to actually reach it, and reach it fast, and the higher the better. 6/

But what about DISTRIBUTION? How will billions of doses of #COVID19 vaccine that get manufactured get from factories to our arms – especially if every dose must stay refrigerated from time of manufacture until injection? This is known as a “cold chain” sciencedirect.com/science/articl… 7/

Any interruption in the refrigeration of a vaccine that must stay refrigerated (e.g., being accidentally left for an hour on a loading dock or in a vial on a counter) can inactivate it. It requires a lot of effort to prevent such breaks in the cold chain. 8/

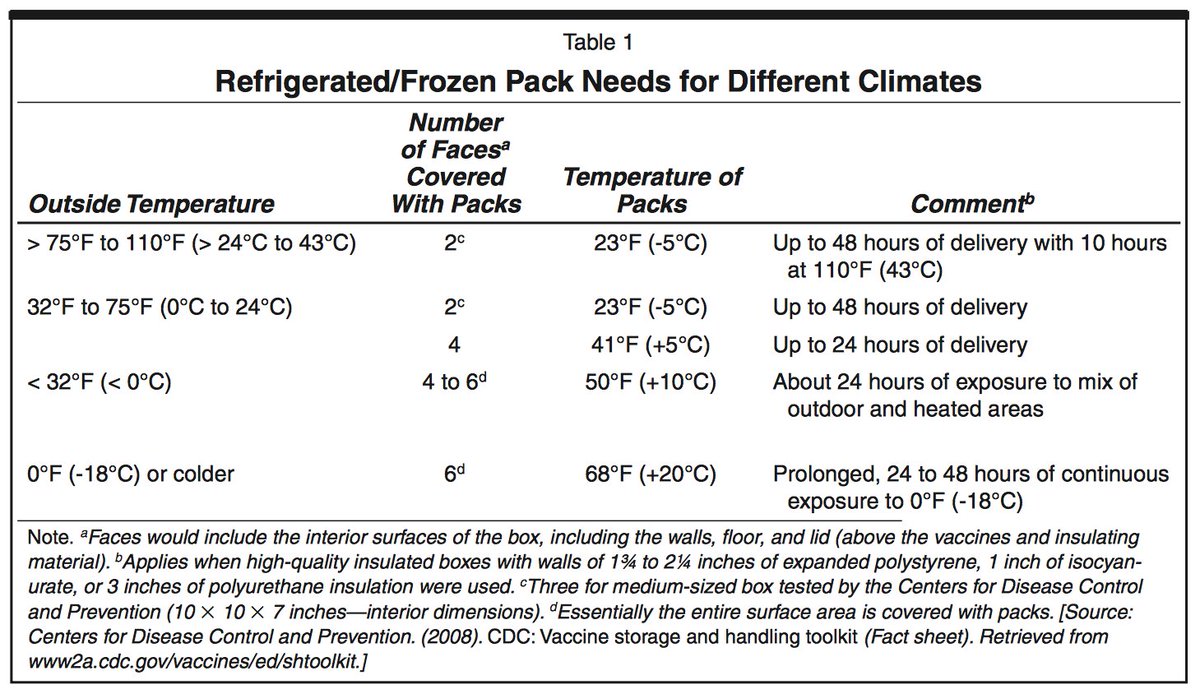

Even the number and placement of ice packs in the boxes containing the shipped vaccines is important. journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.117… 9/

The necessity of monitoring the exposure of vaccines to heat during transport and storage has led to many innovations, including temperature-sensitive vaccine vial monitors and distributed internet-enabled sensors. sciencedirect.com/science/articl… 10/

There are cases where vaccines sent to developing world have been rendered useless. For example, a measles outbreak in Micronesia in 2014 was probably due to cold chain failure cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/m… and of polio in Oman in 1988 likely for same reason sciencedirect.com/science/articl… 11/

And surveys of cold chains often find problems in both the developing world (e.g., India scielosp.org/article/bwho/2…) and the developed world (e.g., UK bmj.com/content/bmj/30…). 12/

Plus, TOO COLD a temperature is also a problem! It can inactivate a vaccine. Vaccine exposure to temperatures BELOW recommended ranges occurred during shipments in 38% of studies from higher income countries and 19% in lower income countries. sciencedirect.com/science/articl… 13/

It turns out that two of the frontrunners for a #COVID19 vaccine require a cold chain: fiercepharma.com/manufacturing/… 14/

Indeed, most (if not all) of the likely #COVID19 vaccines will need some sort of cold chain (with specific tolerances for requisite cold temperature or for permissible time at room temperature). supplychaindive.com/news/coronavir… #coldchain 15/

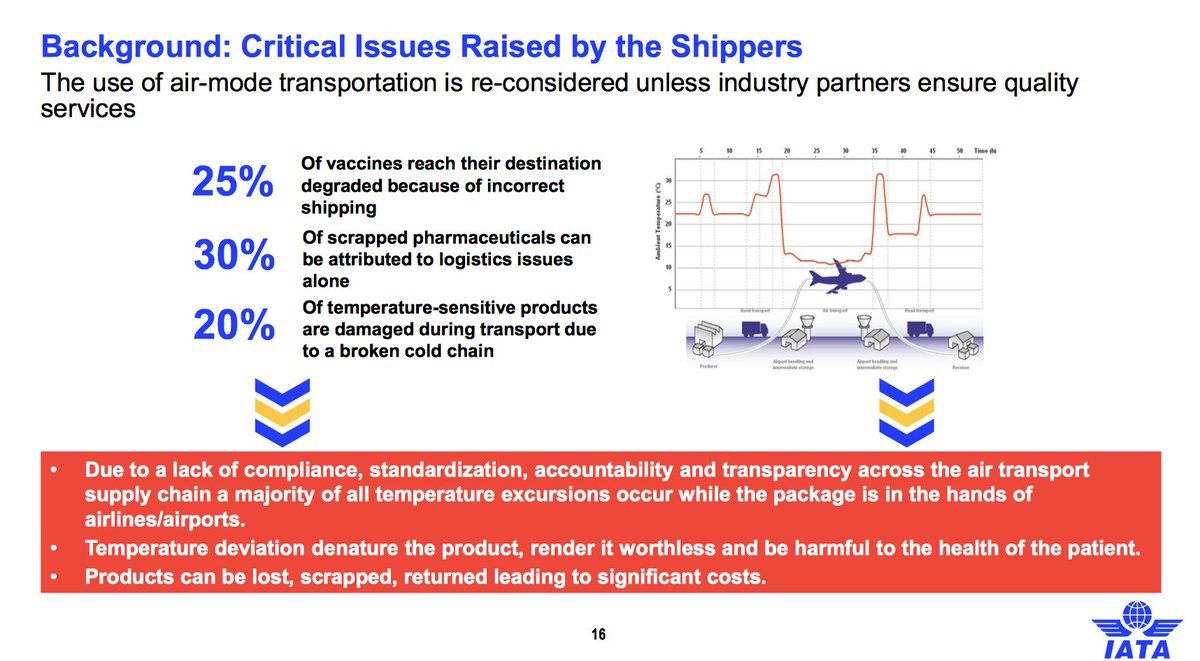

According to @iata, by 2022, world sales of cold-chain drugs will likely top $416 billion, in a global biopharma market >$1.43 trillion. iata.org/contentassets/…

At present, perhaps 25% of vaccines reach their destination degraded because of incorrect shipping. 16/

At present, perhaps 25% of vaccines reach their destination degraded because of incorrect shipping. 16/

So, indeed, many (or all!) #COVID19 #SARSCOV2 vaccines will face the important and demanding challenge of requiring a #coldchain. 17/

But the problem of transporting an agent for vaccination in a way that protects its efficacy is not a new one!

Let’s take this thread in a fascinating historical direction? bbc.com/news/world-asi… 18/

Let’s take this thread in a fascinating historical direction? bbc.com/news/world-asi… 18/

Edward Jenner proved the utility of vaccination in 1798, by taking the pus from someone with cowpox (a mild disease) and injecting it into another person, so as to make them immune to the much deadlier disease of smallpox (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Je…). 19/

As discussed in #APOLLOSARROW, Jenner’s key innovation was to do a *challenge trial*: after putting cowpox pus into the arms of 8-year-old James Phipps, he later deliberately infected him with smallpox!

Some have proposed this for COVID19, too. sciencemag.org/news/2020/07/c… 20/

Some have proposed this for COVID19, too. sciencemag.org/news/2020/07/c… 20/

But how could this cascade from person-to-person be maintained for early vaccination against smallpox, two centuries ago, when there was no refrigeration? 21/

It was possible to take lymph from a person who recovered from cowpox, put it between two sealed glass plates, and ship it somewhere else for use, but it often degraded and was ineffective. There was no cold chain. 22/

An alternative was to transport the vaccine "arm-to-arm." The first person would be vaccinated by smearing vaccine onto their arm with a needle. A week later, when a cowpox pustule developed, a doctor would cut into it and transfer pus on to arm of another person. And so on. 23/

And such people could move, by ship, over a period of weeks, from, say, the UK to India, in a human chain, serving as vessels for the pathogen. 24/

The journey of the vaccine to the arm of the young Wadiyar queen in this image (on the right) probably began, in India at least, with the three-year-old daughter of a British servant named Anna Dusthall. bbc.com/news/world-asi… [thread continues] 25/

On June 14, 1802, Anna Dusthall became the first person in India to be successfully vaccinated for smallpox. Little else is known about her. But all vaccination in India began with her. The following week, five children in Bombay were vaccinated with pus from Dusthall's arm. /26

From there, the vaccine travelled, most often arm-to-arm, across India to various British bases – Hyderabad, Cochin, Tellicherry, Chingleput, Madras and eventually, to the royal court of Mysore, where it may have wound up in the arm of the young queen, Devajammani. 27/

Queen Devajammani agreed to the painting in part to help change attitudes towards vaccination among her subjects.

For scholarship on this painting, entitled Dancing Girls, Madras, c. 1805, by Irish artist Thomas Hickey, see: cambridge.org/core/services/… 28/

For scholarship on this painting, entitled Dancing Girls, Madras, c. 1805, by Irish artist Thomas Hickey, see: cambridge.org/core/services/… 28/

This action by the queen in 1805 also highlights another ongoing challenge, beyond vaccine distribution, that will be relevant to confronting COVID19: public health education. People will have to be encouraged to take a vaccine on a huge scale, and persuaded that it is safe. 29/

And this historical case highlights another broader idea, which is one theme of APOLLO’S ARROW: The Profound and Enduring Impact of Coronavirus on the Way We Live @littlebrown amazon.com/Apollos-Arrow-…: the challenges posed by epidemics have always been a part of our history. 30/

Plagues are not new to our species. They are just new to *us*. 31/

For another "human chain" of "orphan children" assigned the task of being sequentially infected with cowpox during a long ocean journey, for the purpose of transporting the vaccine against smallpox a great distance, see: outono.net/elentir/2020/0… via @CarlosHdezy 32/

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh