Out now in @PLOSBiology, @Kelley__Harris and I try to unravel what altmetrics and the fire hose of social media data really tell us about the potential impacts of research papers. 1/n

journals.plos.org/plosbiology/ar…

journals.plos.org/plosbiology/ar…

First, some background. Academics are *obsessed* with impact. Our entire ecosystem—grants, tenure, publications, etc.—is built around generating new & striking knowledge, with an implicit goal of producing immediate economic, environmental, or cultural impacts. 2/n

Impact is remarkably difficult to measure, and even harder to predict. Remember 2017 Nobel winner Jeffrey Hall? He left academia a decade prior, in part because the impact of his work was not immediately appreciated by funders and publishers. 3/n

qz.com/1095294/2017-n…

qz.com/1095294/2017-n…

Social media provides a tantalizing opportunity to think about and measure a paper's potential for impact. When a paper is shared on Twitter, we can observe in real-time how much a given study is shared across various audiences. 4/n

A crucial component of this analysis is characterizing those audiences. If I hand you 2 papers and say one received 1,000 tweets from scientists and the other received 1,000 tweets from #KpopTwitter stans, your perception of their potential impacts will be vastly different. 5/n

How do we know those tweets come from a particular group of users? Traditionally, user classification is based mainly on information in their Twitter bio. If we're lucky, that bio will be accurate and informative (see that of yours truly). 6/n

However, bios can be noisy, sparse, or even dishonest. Consider my former dissertation committee member, @gabecasis. Though we all know Gonçalo is a scientist through and through, that's hard to glean from his rather vague, laconic bio (not a judgement statement, btw 😉) 7/n

By looking at the bios of a Twitter user's followers, however, we gain vastly more information that helps us accurately characterize the focal user, albeit indirectly. 8/n

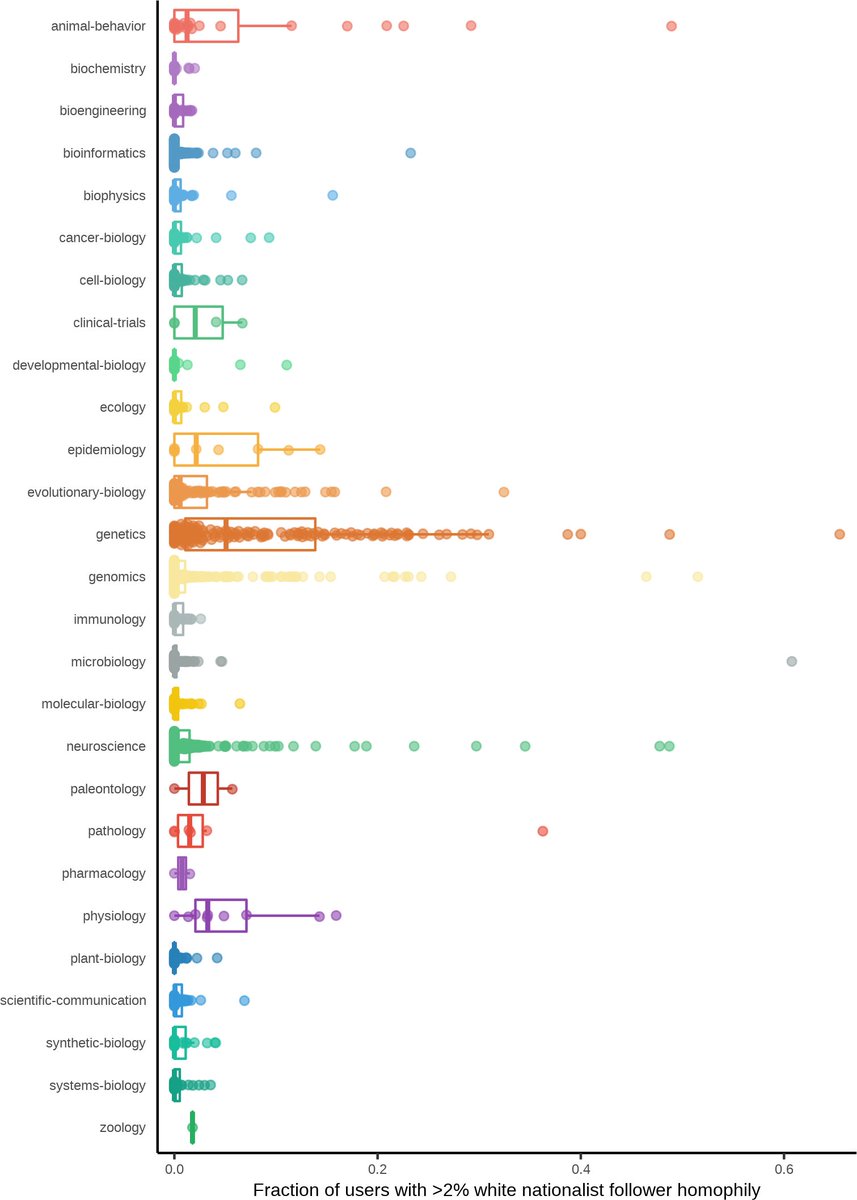

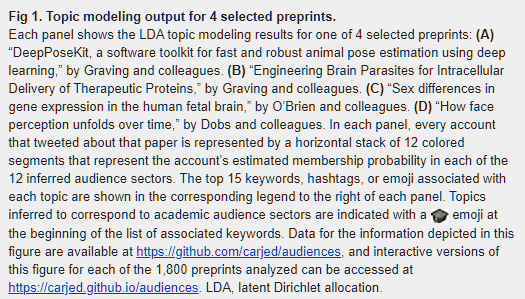

We apply topic modeling to these collections of follower bios to agnostically extract the latent characteristics of the audience sectors engaging with a given preprint. Each user is thus quantitatively represented as a mixture of these inferred audience sectors 9/n

Here's an example of a preprint by @jgraving that attracted neuroscientists, conservation ecologists, data scientists, video game developers, and graphic designers, among others. 10/n

...and here's a preprint that attracted geneticists, bitcoin investors, vegans, science fiction/fantasy writers, and a whole lot of far-right conservatives and white nationalists 11/n

This gives us a fresh perspective on how we interpret impact, at least among online social networks—in some cases it might reveal new opportunities for interdisciplinary collaboration, but in others we might discover uncomfortable patterns of political misappropriation. 12/n

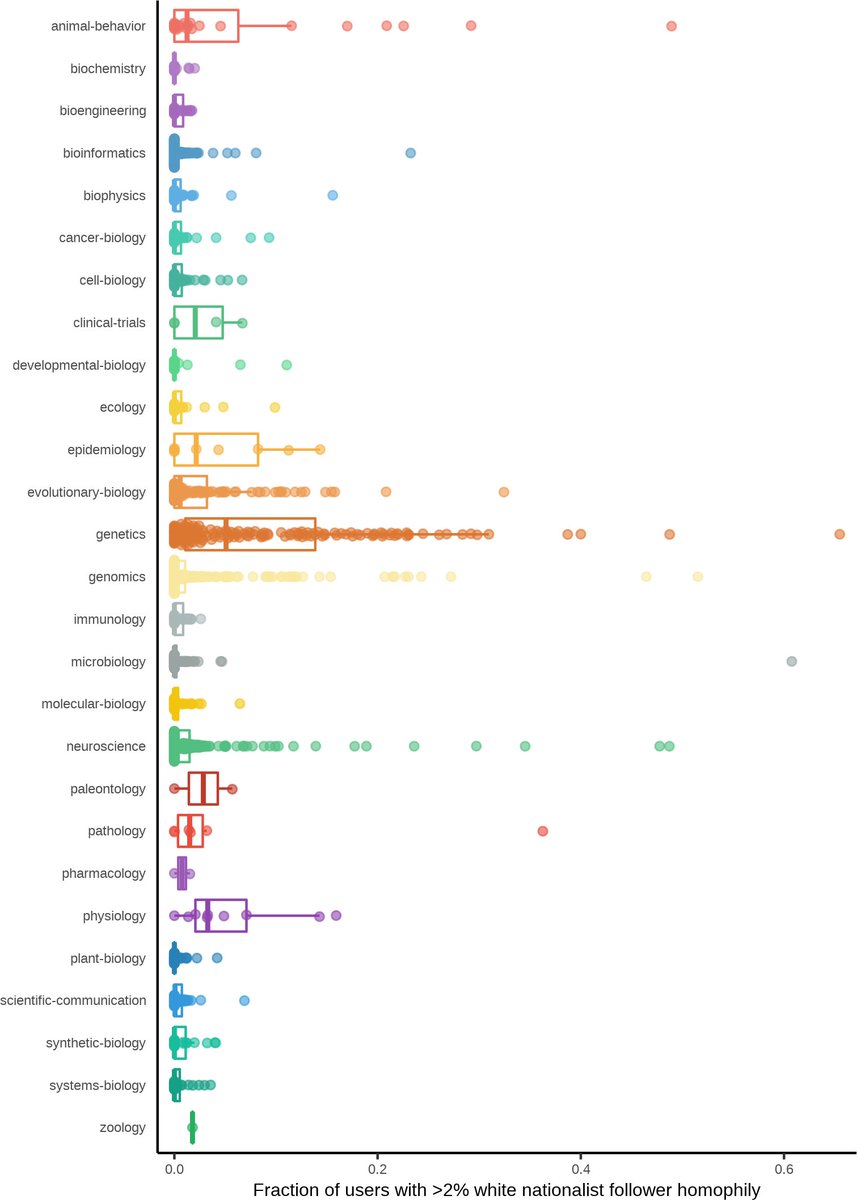

In fact, we find 10% of the preprints analyzed had sizable (>5% of the total) audience sectors associated with white nationalist communities.

Several colleagues have expressed that this isn't (or shouldn't be) surprising, and perhaps they're right! 13/n

Several colleagues have expressed that this isn't (or shouldn't be) surprising, and perhaps they're right! 13/n

What's troubling is that, on a platform celebrated by scientists for providing unprecedented access to lay audiences and making "scicommers" out of us all, these bad actors have the potential to completely dominate the online conversations surrounding our work. 14/n

In extreme cases, over half of the tweets about a given article come from users with much higher than average association with white nationalist networks, giving concrete evidence that science cannot be decoupled from the political environment in which it is carried out. 15/n

As a community, academia still doesn't know what to do with social media. In many ways, #ScienceTwitter is just a digital extension of the ivory tower, oblivious and impenetrable to "outsiders" seeking to engage with our work. 16/n

Sure, we have convinced ourselves that being active on Twitter equates to "outreach," but our study found that 96% of highly-tweeted preprints have majority academic audiences, suggesting very few papers ever penetrate the public mindset 17/n

In short, most of us are completely failing to use social media as a mechanism of positive outreach, and we are largely oblivious to the negative impacts of research shared openly on Twitter. 18/n

I hope our study starts conversations among scientists about what our social media presence can and cannot accomplish, and how we can document and share our research in a way that maximizes public scientific literacy and reduces potential harm. 19/n

Thanks to @DocEdge85, @Graham_Coop, @jgschraiber, and @jrossibarra for their comments on an early draft of the paper, and thanks especially to @E_BeyersCarlson, whose topic modeling dissertation chapter with @syardi was a huge inspiration for planting this idea in my head. 20/n

Also thanks to @altmetric for making their data available free of charge, @richabdill and @blekhman for the rxivist.org API, and the Harris lab for their feedback over the last several months. 21/n

If you want to dig into the plots and data in the paper, we have a little dashboard with lots of interactive stuff you can play with, available at carjed.github.io/audiences/ 22/n

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh