ANIMAL ENERGY, a THREAD on the surprising history of industrial capitalism's core and periphery:

You'd think animals are a primitive power source quickly discarded once fossil fuels entered the picture. But you'd be wrong. Animal power concentrated in the 19c industrial core.

You'd think animals are a primitive power source quickly discarded once fossil fuels entered the picture. But you'd be wrong. Animal power concentrated in the 19c industrial core.

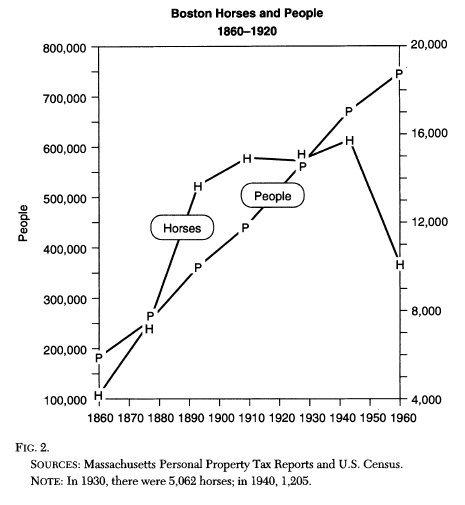

As Clay McShane showed long ago, urban growth in the US Northeast was fundamentally dependent on horses. Look at these incredible population figures. Even as rural migrants and int'l immigrants streamed into Boston, it's horse population grew even faster. jstor.org/stable/3185479

Horsepower increased on the intensive margin, too, as horses got much bigger. Look at the size of these enormous draft horses! Urban horses pulled streetcars and delivery wagons. Rural horses plowed fields and did other farm work.

nj.com/bergen/2018/05…

nj.com/bergen/2018/05…

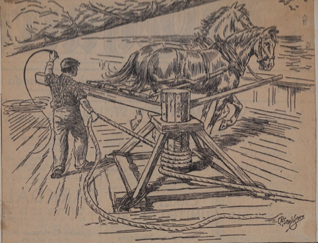

Horses did all kinds of other work, too. This is a "horse boy" managing horses turning a capstan for lifting anchors and heavy cargo aboard a ship on the Great Lakes in the late 1800s.

…ges.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/121828/data

…ges.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/121828/data

Animal power was less prevalent on the industrial periphery, where enslaved, enserfed and other coerced rural labor toiled to supply raw materials. Allen Mikhail's fantastic article, "Unleashing the Beast," tells the tale of how this happened in Egypt.

ahr.oxfordjournals.org/content/118/2/…

ahr.oxfordjournals.org/content/118/2/…

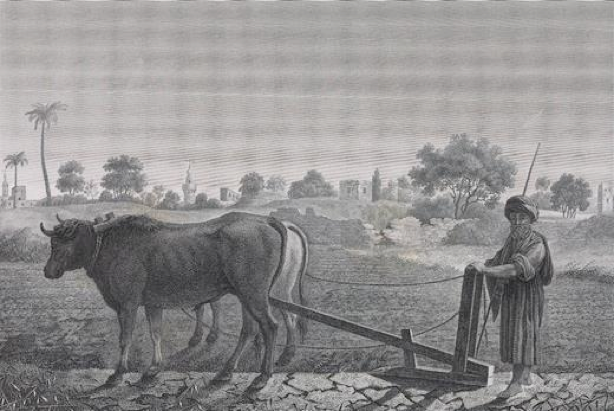

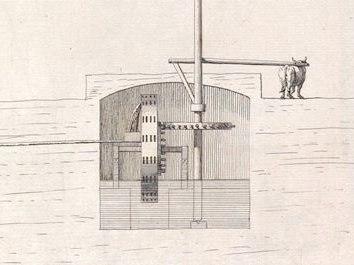

Animals were wealth in 18c Ottoman Egypt. Allen details some of the sophisticated financial arrangements in which people owned shares of multiple animals. Infrastructure in the Nile Valley, especially the all important irrigation works, were literally geared to animal power.

But in the last decades of the 1700s, repeated environmental disaster produced drought, famine and epidemics. Animals died in droves, impoverishing the peasantry. Concomitantly, a complex political shift detached Egypt from Ottoman suzerainty and empowered landholding elites.

The result was that landholders gained leverage over peasants and worked them on newly assembled cotton plantations producing for Euro markets. Infrastructure designed for animals became useless; energy now came from human labor. Compare this pic from 1880s to previous.

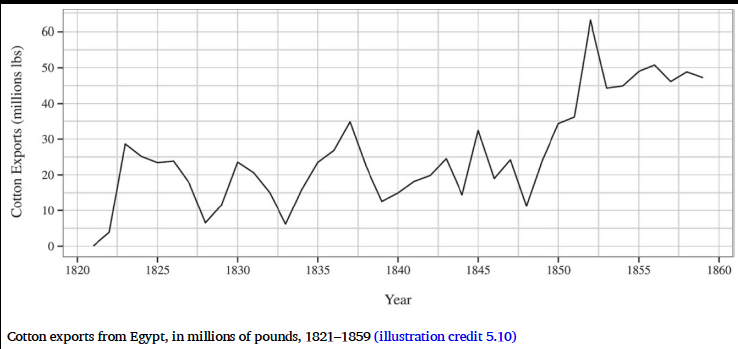

This chart, from Sven Beckert's monumental Empire of Cotton: A Global History, suggests that rising cotton production was compatible with technological and energy decline, at least in some respects.

The diverging trajectories of North and South in the US suggest an interesting parallel. In a way, N and S lived Egypt's two futures: one with animal and industrial energy for domestic development, the other with mostly human-powered commodity production for global exports.

It's not that animal and steam power were entirely absent from the slave South, but enslaved human labor, under the full and coercive control of slave owners, was the key to the rise of US cotton capitalism. As @CC_Rosenthal and many others show in different ways...

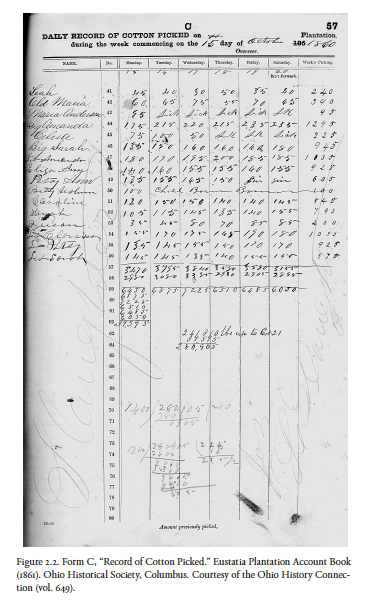

...southern innovation revolved around getting the most out of enslaved labor. New kinds of cotton, management techniques, and attack dogs pressed enslaved people to produce more. Record keeping was key

books.google.com/books?vid=OCLC…

books.google.com/books?vid=OCLC…

Northern industrialization came with its own coercions and was deeply complicit in slavery. It also made more use of animal power alongside the rapid rise in the consumption of fossil fuels. Many came to see technology and new sources of energy as liberatory, compared to slavery

The political economist E. Peshine Smith and the philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson evinced this thinking in the 1850s

books.google.com/books?vid=OCLC…

rwe.org/iii-wealth/

books.google.com/books?vid=OCLC…

rwe.org/iii-wealth/

Here's an 1885 certificate of the PA State Ag Society. It contrasts slavery and technological backwardness on the bottom left with individual freedom and tech progress (in the form of a mechanical reaper) on the bottom right. Power source is a horse. digital.librarycompany.org/islandora/obje…

The internal combustion engine and electrification began to marginalize previously central animal, especially horse, power in the industrial core. But this didn't start to happen till the 1890s and wasn't complete until at least WWII.

/fin

/fin

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh