Check out our new paper on the need for better understanding of academic searching:

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jr…

#InformationRetrieval #MedLibs #EvidenceSynthesis

A thread with our key points... (1/20)

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jr…

#InformationRetrieval #MedLibs #EvidenceSynthesis

A thread with our key points... (1/20)

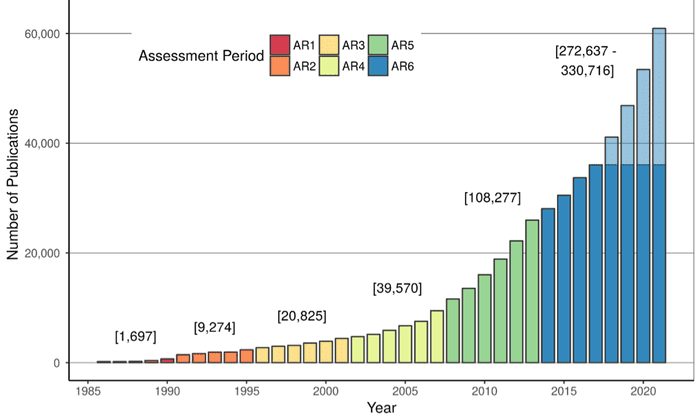

We agree with others that we now face an 'information crisis' (#infodemic). There is SO much published research we need to find and digest.

Doing this reliably requires systematic review approaches, but even then, it's hugely challenging to find all relevant research.

(2/20)

Doing this reliably requires systematic review approaches, but even then, it's hugely challenging to find all relevant research.

(2/20)

Academic searching/information retrieval is an art form, and there is no 'perfect' search strategy - it takes careful planning and requires substantial skill and training.

These searches are highly complex and must be used in fit-for-purpose bibliographic databases. (3/20)

These searches are highly complex and must be used in fit-for-purpose bibliographic databases. (3/20)

We introduce an updated typology of searching that consists of three main types of searches that we academics routinely engage in;

🔎 'Lookup' searching

🔎 'Exploratory' searching

🔎 'Systematic' searching

(4/20)

🔎 'Lookup' searching

🔎 'Exploratory' searching

🔎 'Systematic' searching

(4/20)

🔎 'Lookup searches' - also called 'known item searches' or 'navigational searches' - are conducted with a clear goal in mind and "yield precise results with minimal need for result set examination and item comparison." doi.org/10.1145/112194…

(5/20)

(5/20)

Here, the goal is to find specific information quickly and efficiently; for example, finding a paper we know should exist, or any highly relevant information on a targeted topic.

The goal here is NOT to be comprehensive, nor improve understanding of the evidence base.

(6/20)

The goal here is NOT to be comprehensive, nor improve understanding of the evidence base.

(6/20)

🔎 'Exploratory searches' - are used to better understand the nature of a topic, involving continued learning by identifying many, sometimes contradicting, knowledge sources to build a mental model on a topic. Our search terms evolve as we go.

ils.unc.edu/ISSS/papers/pa…

(7/20)

ils.unc.edu/ISSS/papers/pa…

(7/20)

Exploratory searches are an integral part of developing a search strategy for a systematic review or (meta-analysis) - they help teach us about an evidence base and how it has been described and catalogued. It is also known as 'scoping'.

(8/20)

(8/20)

🔎 'Systematic searches' - are unique because they aim to: 1) identify all (available) relevant records in a

2) transparent and

3) reproducible manner

There should ideally be no learning by this stage and the search strategy should be unchanged from the protocol.

(9/20)

2) transparent and

3) reproducible manner

There should ideally be no learning by this stage and the search strategy should be unchanged from the protocol.

(9/20)

We describe each of these searches in our paper, and what characteristics and practices are integral to each - in general there is poor 'search literacy' in the research community that results in inappropriate matching of search goals and search systems.

(10/20)

(10/20)

For example - in this (not so) 'systematic' review, the authors conducted searches only in Google Scholar (onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.111…), a search system designed for lookup searches, and one NOT suitable for systematic searches (onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.10…)

(11/20)

(11/20)

Many people misunderstand what systematic searches should and should not entail, leading to criticisms of the systematic review methods.

e.g. that they should not entail 'hermeneutic circles' of iterative learning and are thus too rigid. tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.108…

(12/20)

e.g. that they should not entail 'hermeneutic circles' of iterative learning and are thus too rigid. tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.108…

(12/20)

In practice, however, systematic searches should always be preceded by a thorough exploratory search phase, which in systematic reviews is called 'scoping'.

environmentalevidence.org/guidelines/sec…

(13/20)

environmentalevidence.org/guidelines/sec…

(13/20)

We introduce a 'search triangle' to help clarify this concept. Efficient and effective searching only works when all three concepts (search goals, search systems, and search heuristics) are matched well.

(14/20)

(14/20)

We make three important calls to action regarding academic searching that aim to avoid inappropriate use of search systems that weren't designed for rigorous exploratory or systematic searching.

(15/20)

(15/20)

1) We need better awareness of the intricacies of academic searching and acceptance of the importance of matching goals (the 'why'), systems (the 'what'), and heuristics (the 'how') in all academic searching.

(16/20)

(16/20)

2) We need better search education, aiming towards 'search literacy' as the norm.

This requires an appreciation of information science as a vital research skill, and the establishment of training across all research institutions.

(17/20)

This requires an appreciation of information science as a vital research skill, and the establishment of training across all research institutions.

(17/20)

3) We need fit‐for‐purpose search systems, designed to support each of the three search types.

Systems designed for rapid lookup are not fit for systematic searches. Systems designed for systematic searches need to facilitate bulk downloads and be fully transparent.

(18/20)

Systems designed for rapid lookup are not fit for systematic searches. Systems designed for systematic searches need to facilitate bulk downloads and be fully transparent.

(18/20)

Researchers should put pressure on search system providers to tailor their products to our needs. But to do that, we need to know and accept what those needs are in the first place.

(19/20)

(19/20)

Finally - algorithms (e.g. Google Scholar's) cherry pick evidence for us and we may have no idea it's happening.

If we don't urgently improve understanding of academic searches, we risk being biased and influenced by what system developers think we want to see.

(20/20)

If we don't urgently improve understanding of academic searches, we risk being biased and influenced by what system developers think we want to see.

(20/20)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh