My take on last week's Privacy International and La Quadrature decisions, and implications for UK data protection adequacy. cyberleagle.com/2020/10/hard-q…

Thread summary of some central points follows. (The post is a long read and covers much more.)

The cases concern more than compelled retention of communications data. They include legislation mandating service providers to conduct automated analysis of communications data to detect terrorism, and to provide real-time feeds to security and intelligence authorities. 1/16

The CJEU draws a line between activity on the service provider side (retention and analysis) and transfer of data to the authorities. In limited circumstances, or for some kinds of data, the former may permissibly be general and indiscriminate; the latter not. 2/16

The distinction between legislation directly imposing blanket obligations on all service providers, and that conferring discretionary powers to require individual service providers to engage in stipulated activities, is also becoming more significant. 3/16

Legislation imposing general and indiscriminate communications data retention obligations is generally speaking incompatible with EU law, other than for source IP addresses and user identity data. 4/16

However, an instruction for general and indiscriminate retention of communications data, and mandated general and indiscriminate automated analysis to detect a terrorist threat, are permissible (subject to safeguards) while a serious threat to national security exists. 5/16

Targeted retention (for instance according to categories of person or geographic criteria objectively connected to the purpose of combating serious crime) is permissible for limited purposes and subject to safeguards. 6/16

A blanket legislative requirement imposed on all providers is readily characterised as general and indiscriminate. But how to determine whether a discretionary power mandates general and indiscriminate, or targeted, activities? 7/16

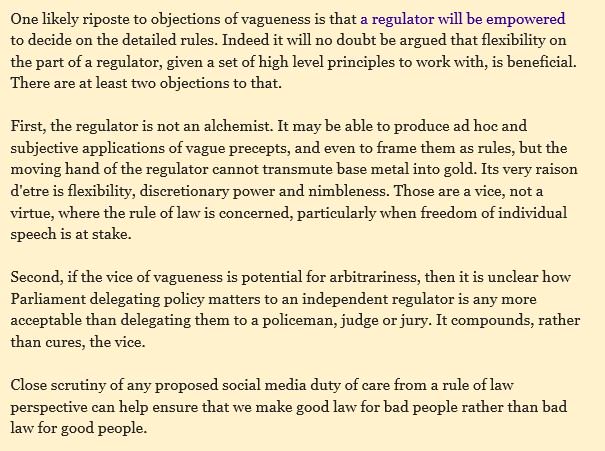

The CJEU reiterates that legislation must lay down clear and precise rules, and indicate the circumstances and conditions in which a measure can be adopted. It adds that the legal basis permitting the interference must itself define its scope. 8/16

Does a Member State have to list in its own legislation a set of substantive conditions, such as according to category of person or geographic criteria, constraining the exercise of a discretionary power? 9/16

Or is it sufficient for the legislation to require observance of necessity and proportionality and to lay down factors to be taken into account when exercising the power, accompanied by safeguards? 10/16

Under the IP Act the Secretary of State must consider it necessary and proportionate to exercise her data retention power, and is required to take into account specified factors. Her decision is subject to Judicial Commissioner approval. 11/16

In April 2018 the High Court in the Liberty case said that sufficed. It was not necessary, and would be impractical, to list conditions in the legislation. Also, it could not be said that the legislation permitted general and indiscriminate retention of communications data. 12/16

As to whether an approach more reliant on safeguards than limitations is sufficient, these CJEU decisions appear to lean further towards requiring substantive conditions to be spelled out in binding legislative instruments. 13/16

The potential impact of that is heightened by the distinctions that the CJEU has now made between different kinds of service provider activity and access by the authorities, which are made subject to differing conditions and are permissible for differing purposes. 14/16

An avowedly bulk power such as the IP Act communications data acquisition warrant, which while requiring necessity and proportionality does not make such differentiations on the face of the legislation, now appears less likely to pass muster. 15/16

Overall, the IP Act powers should be evaluated from two perspectives: acceptability of soft versus hard limitations, and compliance with the substantive limits applicable to different categories of data retention and transmission power now articulated by the CJEU. 16/16

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh