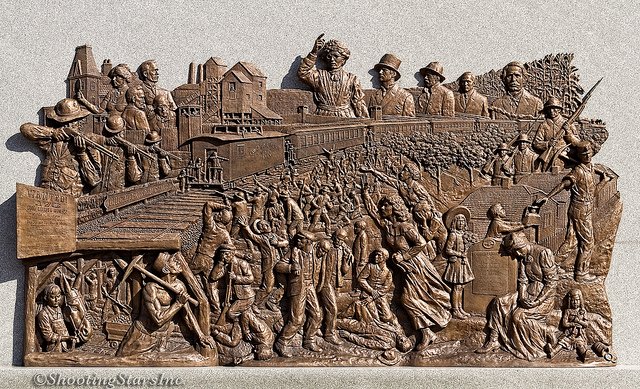

This Day in Labor History: October 19, 1935. John L. Lewis punches Carpenters president Big Bill Hutcheson in the face on the stage at the AFL Convention in Atlantic City. Let's talk about this bizarre moment and the creation of the CIO!

The United Brotherhood of Carpenters was the largest member of the AFL. It was also among the most politically conservative unions.

While, like much of the AFL, the UBC was technically nonpartisan in these years, Hutcheson was an active Republican and would remain so throughout his life, openly campaigning for Republican candidates against Franklin Roosevelt.

His son, who took the union over upon his death in 1952, shared his political conservatism. In fact, the UBC would not endorse a Democrat for president until Lyndon Johnson in 1964.

Hutcheson would become a member of America First before World War II, castigate FDR for not supporting the House Un-American Activities Committee, and oppose Harry Truman’s proposal for a national health program. He also opposed unemployment insurance.

For all the criticism the old AFL gets today for its politically conservative positions, it is worth noting that even a more aggressive AFL leader would have faced enormous resistance from his constituent unions. It is a federation after all, not a single organization.

The Carpenters were distinctly uncomfortable with not only the idea of industrial unionism but the industrial workers. The AFL gave the UBC jurisdiction over the timber industry. Loggers in the Pacific Northwest went on strike in 1935.

The Great Strike finally organized the loggers who had agitated for unionism since their days as IWW members twenty years earlier. The Carpenters gained 100,000 new members.

But the UBC feared the influence of a bunch of ex-Wobblies and current commies (of which there were no small number, especially in Washington although decidedly less so in Oregon). So they did not give the loggers full union rights, including the right to vote for union officials

Hutcheson already ran one of the least democratic unions in the United States and was not about to let a bunch of commie treecutters in an industry marginal to the union’s central mission undo the work he had done building his empire.

The loggers seethed under Carpenters’ representation, such as it was.

John L. Lewis saw the labor movement very differently than Hutcheson. Not that Lewis was more democratic or some sort of raging leftist. Far from it. Lewis and Hutcheson had even been allies in the past, playing poker together regularly when they both lived in Indianapolis.

But Lewis knew that his laborers, one of the only industrial unions in the United States, required the organizing of the nation’s other industrial laborers to create a stable union. Lewis would later personally engineer the organizing of the steel plants for this reason.

Lewis and other labor leaders were also concerned that AFL president William Green’s tepid response to the Great Depression was undermining the labor movement. During the early 1930s, the AFL was losing up to 7000 members a week.

Lewis demanded that Franklin Roosevelt aggressively move to pass legislation that helped workers.

He also encouraged the AFL to give up its long-standing animus to the industrial workers that made up a huge chunk of the American labor force and engage in an organizing campaign of workers who wanted to join unions. Green and Hutcheson demurred.

The growing tensions between the craft unions and those who sought to organize the millions of under- and unemployed Americans demanding economic change grew through 1934, as revolts around the nation made many Americans fearful for capitalism’s future.

But the AFL still largely refused to act. By the time the AFL met in Atlantic City in the fall of 1935, Hutcheson was determined to squash any industrial unionism talk. At the convention, Hutcheson was running the floor.

When a rubber worker began speaking about a point of order, Hutcheson interrupted him. Lewis quickly responded. When Hutcheson called Lewis a “bastard” in response, Lewis jumped on the stage and punched him in the face. He then re-lit his cigar and calmly returned to his seat.

Some have questioned whether Lewis had planned to punch Hutcheson. I kind of doubt it but he certainly took advantage of the situation to very publicly announce to the AFL old guard that he was serious about organizing the nation’s industrial workers.

Three weeks after this dramatic event, Lewis, David Dubinsky of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) and Sidney Hillman of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers (AGW) formed the Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO) within the AFL.

This set the stage for the withdrawal of the industrial unionists from the federation in 1937, when the CIO became the Congress of Industrial Organizations.

In the timber industry this split gave the radicals the room to bolt the Carpenters and found the International Woodworkers of America (IWA) in 1937.

If there’s one thing Hutcheson loved, it was a jurisdictional battle and he went full-bore against the radical loggers, using his Teamsters allies to not load IWA processed wood, among other intimidation tactics.

The IWA itself was torn apart by communism, requiring the personal intervention of Lewis before the union fell apart. By 1940, the battle faded and about 2/3 of the loggers were in the IWA and 1/3 in the UBC.

The bickering between these two unions would never fully end and even when the IWA could no longer sustain itself in 1987, it merged with the International Association of Machinists rather than create one union in wood.

While any number of books discuss the legendary punch, the stuff on the timber industry I use here to deepen the discussion comes from my own book.

amazon.com/Empire-Timber-…

amazon.com/Empire-Timber-…

Back on Friday for a discussion of the everyday work that unions do--the union meeting and what it means.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh