We have more information now about the case of #ClaireParry, following news reports of the judge’s sentencing remarks. And it is complicated, more so than I had appreciated when I tweeted last night.

So a brief [THREAD] to look at what seems to have happened.

So a brief [THREAD] to look at what seems to have happened.

https://twitter.com/barristersecret/status/1321156610560057344

It was widely reported yesterday that the defendant, Timothy Brehmer, had been acquitted by a jury of the murder of Claire Parry. It was said that he strangled her after she sent a text message to his wife telling her of their (Parry and Brehmer’s) affair.

https://twitter.com/bbcnews/status/1321085753020026880

It was also reported that Brehmer had admitted manslaughter, but denied intending to kill or cause really serious harm (the necessary intention for murder), claiming that the fatal injuries were sustained “accidentally” during a “kerfuffle”.

As I said yesterday, if the jury were not sure that Brehmer intended to kill or cause GBH, they would have to acquit him. And that, I inferred, was what had happened.

BUT. It’s in fact more complicated than that.

Because it seems that there was another defence as well.

BUT. It’s in fact more complicated than that.

Because it seems that there was another defence as well.

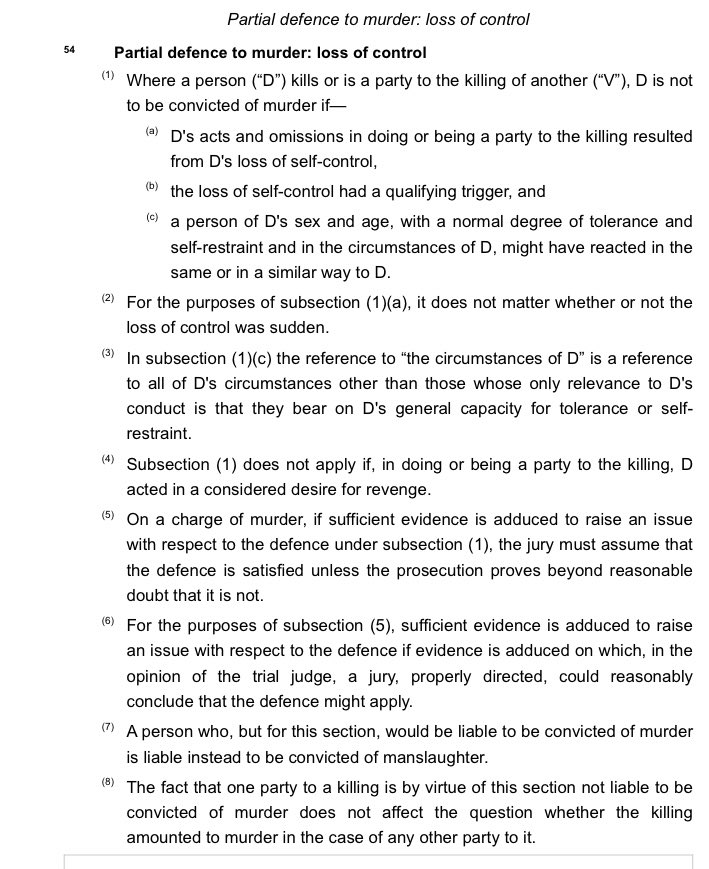

Brehmer also ran the defence of “loss of control”. This is a partial defence, which means it only applies to murder, and has the effect of reducing what would be murder to manslaughter.

The defence is at s54 Coroners and Justice Act 2009:

The defence is at s54 Coroners and Justice Act 2009:

Put simply, the defence applies if a defendant kills, but the killing resulted from a “loss of self-control” and a person of the defendant’s sex and age with a normal degree of tolerance and self-restraint might in the circumstances have reacted in the same or a similar way.

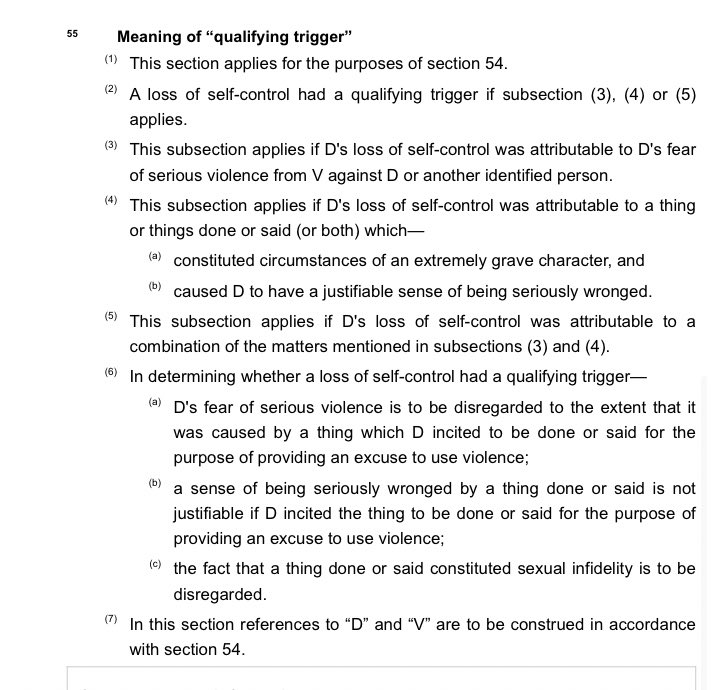

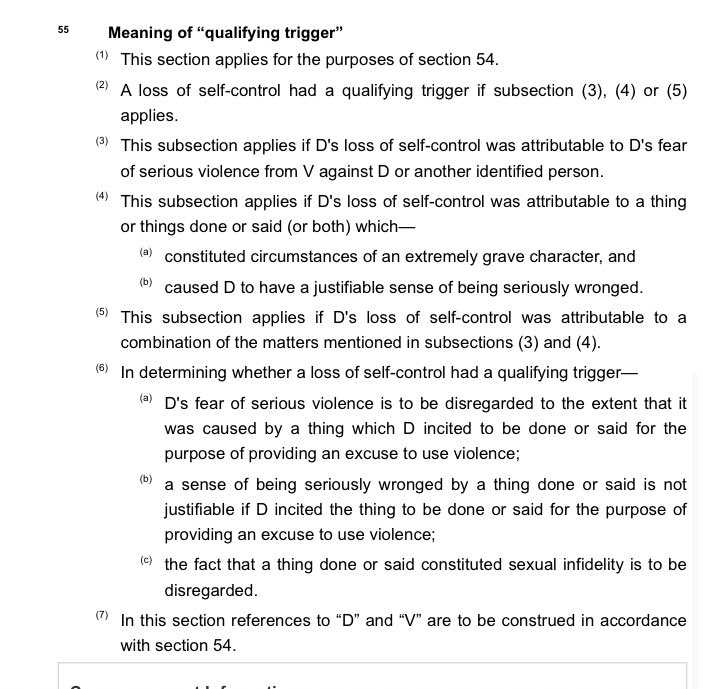

There’s a lot to unpack there. Key is the idea of a “qualifying trigger”. It means that you can’t just lose self-control for any reason - it has to meet the criteria in section 55:

A qualifying trigger includes fear of serious violence, which doesn’t seem to apply in this case.

And also “things said or done which constitute circumstances of an extremely grave character and caused D to have a justifiable sense of being seriously wronged”.

And also “things said or done which constitute circumstances of an extremely grave character and caused D to have a justifiable sense of being seriously wronged”.

Certain things are automatically excluded - infidelity, for instance, does *not* count as a qualifying trigger.

But in this case, it seems that the trigger was not infidelity, but the fact that the victim had told Brehmer’s wife about it. Subtle but important distinction.

But in this case, it seems that the trigger was not infidelity, but the fact that the victim had told Brehmer’s wife about it. Subtle but important distinction.

Again, the burden is on the prosecution to *disprove* this defence. So if the jury isn’t sure, or thinks the defence might be made out, they have to acquit of murder.

So, I wasn’t at the trial but would infer (and I’ll correct if I’m wrong) that the jury were given two possible routes to acquitting on murder:

1. If they weren’t sure of intent to kill or cause GBH

2. If they were sure of that intent, but thought loss of control might apply

1. If they weren’t sure of intent to kill or cause GBH

2. If they were sure of that intent, but thought loss of control might apply

Now, the only verdict the jury gives is “guilty” or “not guilty”. While judges can in exceptional cases enquire as to what basis a jury has convicted of manslaughter, that is very rare.

Normally the judge, who has heard the evidence, decides on what basis she will pass sentence.

Normally the judge, who has heard the evidence, decides on what basis she will pass sentence.

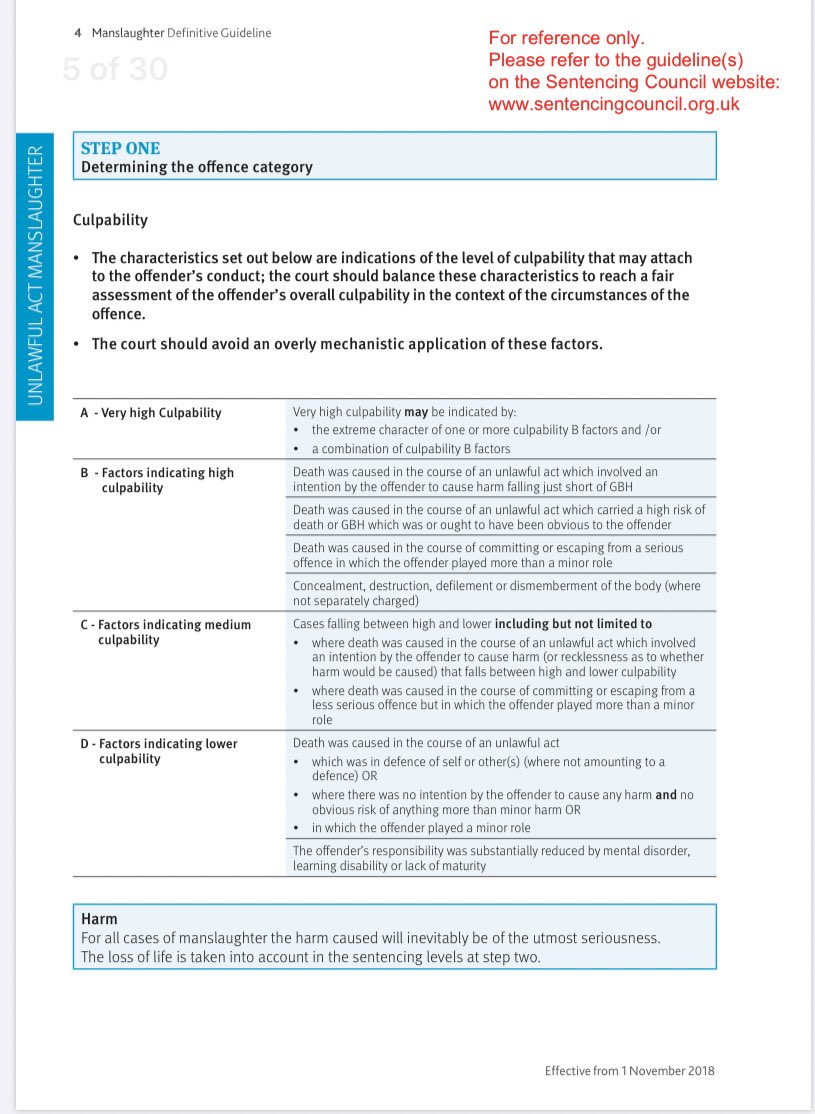

In other words, the judge decides whether it is “unlawful act manslaughter” (ie I used unlawful force but didn’t intend to kill/cause serious harm) or “loss of control manslaughter”.

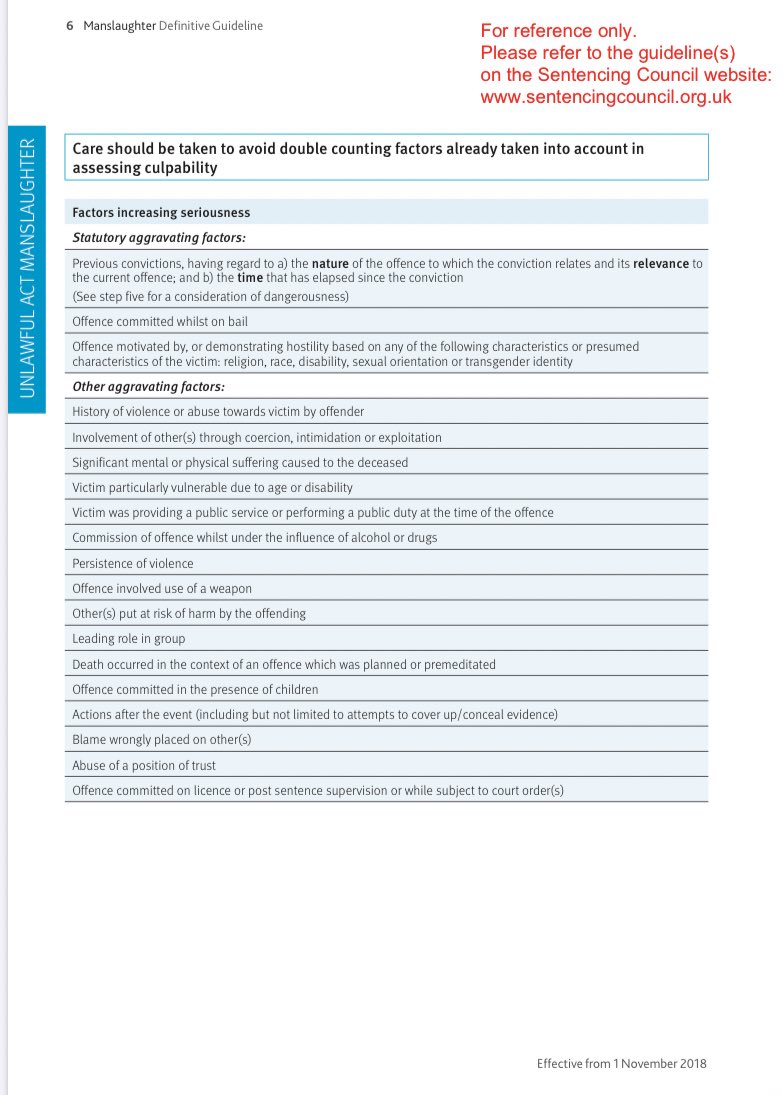

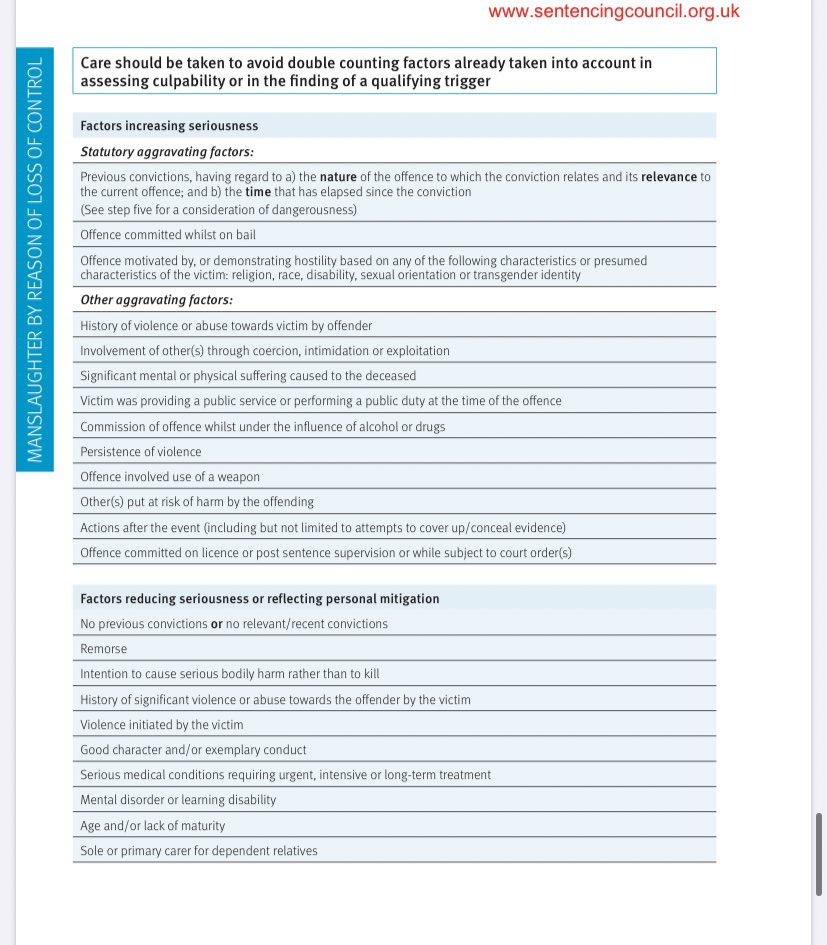

The distinction is important. It makes a difference to sentence.

The distinction is important. It makes a difference to sentence.

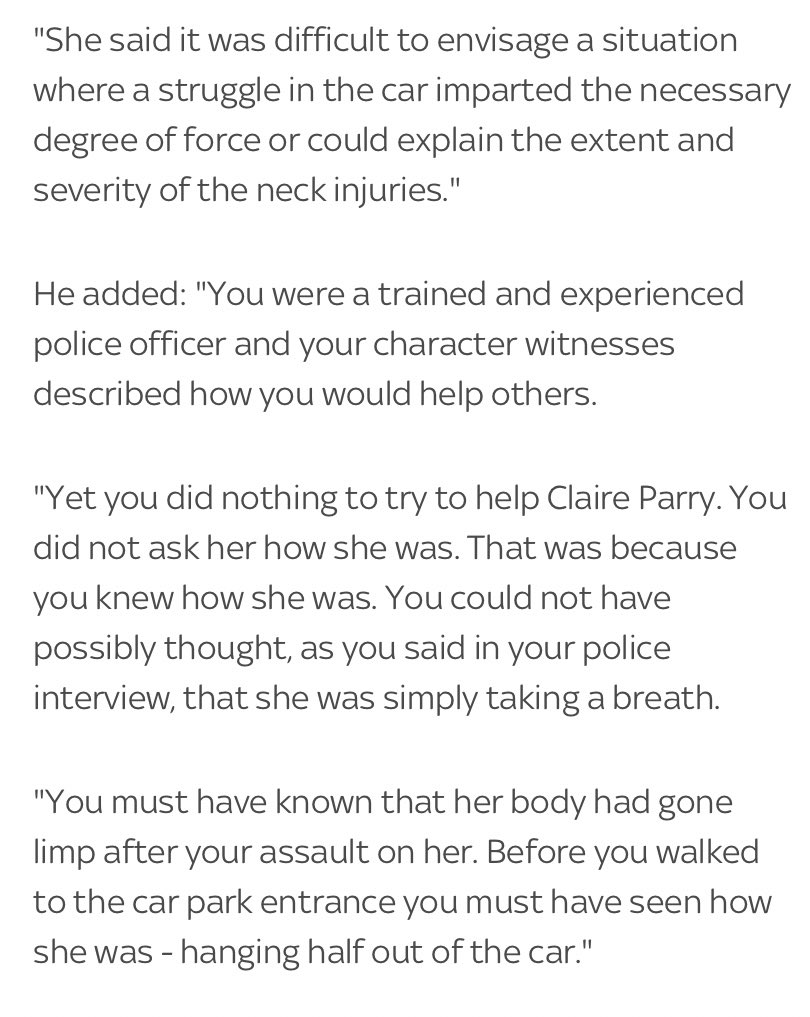

The judge appeared to reject Brehmer’s claim of a “kerfuffle” having inadvertently caused the fatal injury. He seemed sure that Brehmer strangled Claire Party and intended to kill or very seriously harm her.

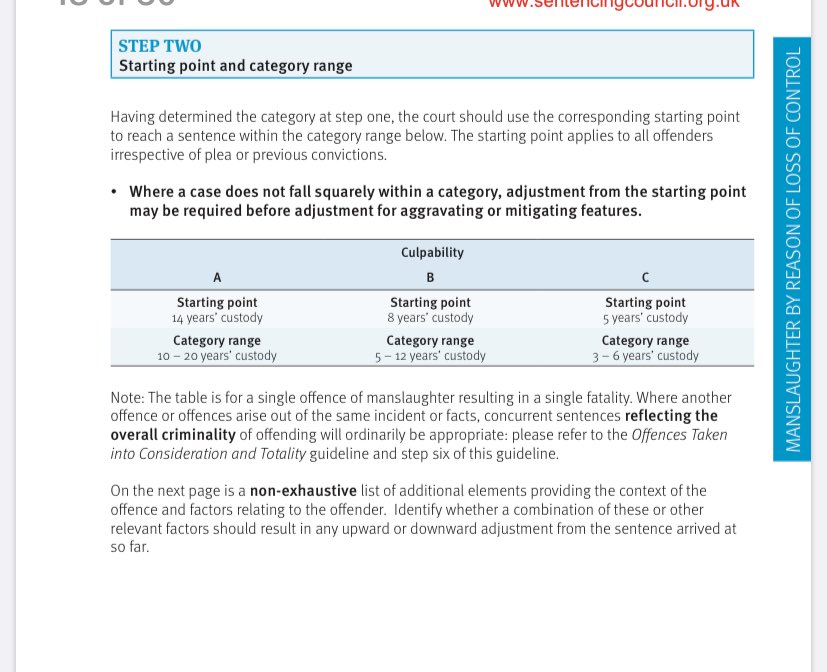

That means that Brehmer was sentenced for loss of control manslaughter, rather than “unlawful act” manslaughter.

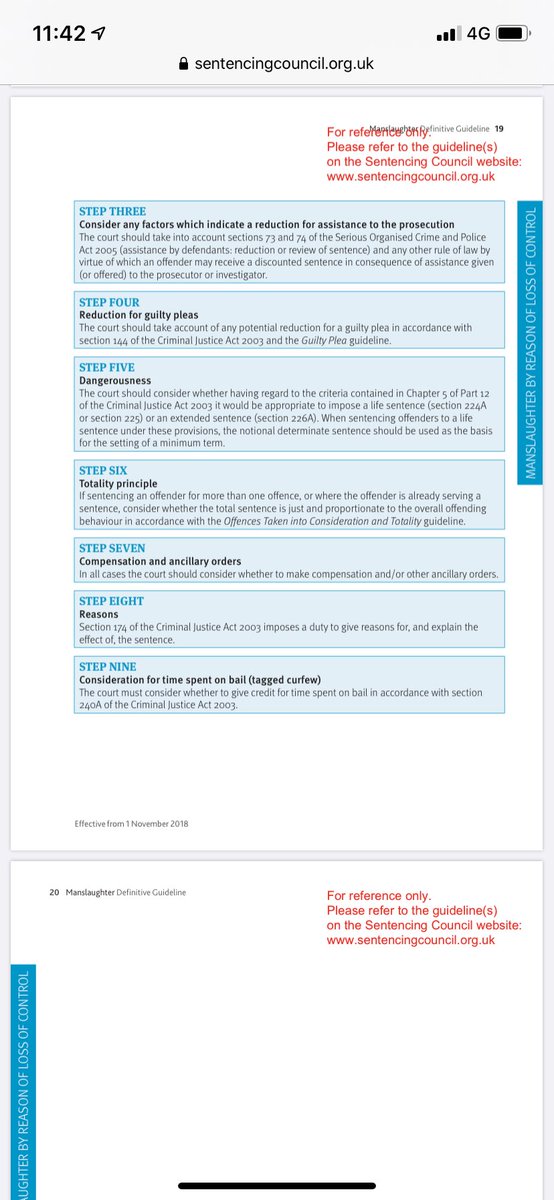

The judge appears to have placed this in the highest Category, and after giving credit for a guilty plea (as the law requires) arrived at a sentence of 10 years 6 months. He will serve 2/3 before release.

I’ll revisit this when we have the full sentencing remarks if it’s wrong.

I’ll revisit this when we have the full sentencing remarks if it’s wrong.

So that seems to be the route taken. But these are complex cases and the detail made publicly available is often inadequate. It causes confusion and worry and does nothing to assist public understanding of the justice system.

The system must do better.

The system must do better.

One thing I would introduce is the publication of the judge’s summing up to the jury. Transcripts are obtained in cases that are appealed, but there is no good reason why they can’t (with careful editing of restricted details) be routinely published after a verdict is delivered.

This would allow the public to see the judge’s summary of the evidence, the applicable law and the exact approach that the jury is directed to take.

Along with publishing sentencing remarks, this would go a long way to demystifying verdicts and sentences.

Along with publishing sentencing remarks, this would go a long way to demystifying verdicts and sentences.

We are still waiting for the sentencing remarks to be published by @JudiciaryUK, but in the meantime there’s further detail here from @Bournemouthecho, which live-blogged the sentence.

There’s an interesting detail here.

bournemouthecho.co.uk/news/18825425.…

There’s an interesting detail here.

bournemouthecho.co.uk/news/18825425.…

The defence submitted that Brehmer should be sentenced on the basis of unlawful act manslaughter. The judge was asked to find that the murder acquittal amounted to the jury accepting (or at least not disbelieving) Brehmer’s account of the struggle.

But the judge refused.

But the judge refused.

The judge sentenced on the basis that Brehmer had deliberately strangled Claire Parry and that the jury had acquitted him of murder because of “loss of control”.

We of course have no idea on what basis the jury actually acquitted. But that’s what the judge decided. And...

We of course have no idea on what basis the jury actually acquitted. But that’s what the judge decided. And...

...as above, the Sentencing Guidelines for “loss of control” prescribe higher sentences than for “unlawful act” manslaughter.

Had the judge not left “loss of control” as an option for the jury, and had he still been acquitted of murder, the sentence would have been much lower.

Had the judge not left “loss of control” as an option for the jury, and had he still been acquitted of murder, the sentence would have been much lower.

There’s been quite a lot of criticism of the “loss of control” verdict. But the key point being missed is that we don’t know whether the jury *did* in fact find loss of control. It was a finding by the judge, which had the effect of ensuring a more severe sentence was passed.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh