I think post-production is the most underrated pivotal element of a TV writer's life. It's probably also the thing I miss the most when I'm between seasons/shows. It was largely a mystery to me even during my five seasons on LONGMIRE, as the writing staff wasn't involved w/ post.

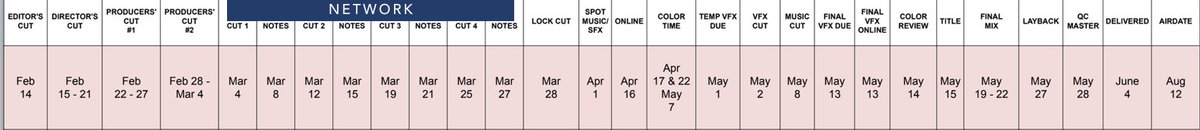

So when I sold DAMNATION and its pilot got the green light to be filmed, it was actually my first time in post-production. The stakes felt crazy high. So did the stress levels. TV schedules are brutally short. I had to catch on really, really quickly.

About my only experiences up to this point were: overhearing my Longmire showrunner on the phone and in meetings discussing post issues (I took mental notes), sitting in with other crew members as Jimmy Muro screened his cut of a LONGMIRE episode and solicited our notes, and...

...for one of my LONGMIRE episodes, I downloaded the dailies & tried editing the episode for myself: selecting the best takes & best camera angles & trying to structure & pace scenes myself. Though I was a terrible amateur editor, that exercise (I spent weeks!) taught me a ton.

But it wasn't adequate prep. Thankfully I had LONGMIRE editor Adam Bluming with me for the pilot, so I was in good, incredibly patient hands. The first thing I had to grapple with was the post-production schedule, which I hadn't internalized at all.

First up is the Editor's Cut. While the episode is being filmed (in my experience, 7-8 filming days), the editor and her or his assistant editor are screening dailies and arranging scenes. They aren't doing this totally freelance, though.

In the prep stage, the writer/producer of the episode ideally has toned the episode for the director. The editor of that episode (in TV there's a rotation of editors) usually sits in on that meaning. In my tone meetings, I go through the script scene by scene, page by page.

I sometimes joke that this is the high point of the episode for me. Every scene exists in its idealized form, outside of time, logistics, & performance. Basically, I try to tell the director, DP, 1st AD, & editor what the purpose of each scene is, what the backstory/subtext is...

...(often the director has just arrived and doesn't know the show or characters yet), & flag details or shots or moments that I don't want to be overlooked. I also give whatever inside info I can in terms of cast & crew: acting tendencies, stronger/weaker departments, etc.

So hopefully, that informs the editor's initial assembly. If I flag a scene as being a suspenseful scene, it should be edited w/ that in mind. At a more micro level, the editor is usually also in constant communication w/ the script supervisor on set, who lets the editor know...

...the director's preferred takes & if there are specific shots designed to cut together. Often, the editor will also compare the footage with the script & hopefully the tone meeting notes & will let the script supervisor or director know if they're missing a shot/detail.

(It goes w/o saying, hopefully, that this is just my own experience. I'm sure there are countless valid approaches.) By the time production on an episode wraps, an editor usually has a couple of days to complete their initial cut of the episode.

The editor then sends that cut to the director, or screens it for them. At this point, as a writer/producer, I'm purposefully out of the loop. The director & the editor both get to have their swings w/o input from the rest of us. But they don't have much time.

In my experience, the director has just about a week to fine-tune (or overhaul) the editor's cut into a director's cut. A week of editing goes by very, very quickly. I wish we had enough time to test out and screen and play with footage in post. But in most TV, you don't.

After the director is satisfied with their cut -- or more accurately, once they run out of time -- it's then handed over to the producer. Each show is different here. On LONGMIRE, our showrunner didn't write scripts, but she was the main creative force & oversaw each edit.

I didn't see a LONGMIRE episode that I wrote until it aired. On DAMNATION, I approached it a bit differently: I had the director's cut sent to the episode's writer, to the brilliant Adam Kane (our directing producer), and to me. We each screened it separately.

I would then have the episode's writer send their notes to Adam & myself, & we would select which of these notes to pass along to the editor. For cohesiveness, I think it's important for a show to have a central sensibility & not three separate, shifting sensibilities.

Thankfully, me & Adam's sensibility overlapped hugely & we quickly came up with a great system. I would basically have 7 days to come up with the first producer's cut. For each episode, Adam would spend the first 2-3 days getting the cut as close as possible to what we wanted.

As a showrunner, this was huge because for a good chunk of the season, the writer's room is working on one episode, a writer is outlining another ep, a writer is writing another, another ep needs to be prepped, another is being filmed, & another is at a different stage of post.

So it's not uncommon for 6-7 episodes to be at a different stage of construction at the same time, & as showrunner it's my job to make sure they're gelling creatively & efficiently, & to intervene if they aren't.

So having an extra couple days to be in the writer's room, or prepping the next director, or revising a script, or tweaking a different episode in response to network notes: invaluable. Thank you forever, Adam Kane. Anyway...

Most director cuts are anywhere from 5-10 minutes over time. Part of the producer's job is to get it to time. By the time Adam would get an episode to me, almost all major hiccups would be worked out, & it'd be maybe 2-3 minutes over time. Huge.

So then I would fully step in. And so after screening Adam's cut -- usually a couple of times -- I'd jump into it with the editor, usually remotely: post & writer's room was in LA, production in Calgary, & I would fly back and forth.

The first step is usually to identify if there's any missing shots or scenes that just don't work. Thankfully on DAMNATION, we were budgeted two days of second unit filming per episode: a small splinter unit, usually headed by Adam Kane, would pick up inserts or missing shots...

...or simple scenes w/ minimal dialogue & one or two cast members. So during my cut, I'd put together a wish list of shots, then confer w/ Adam & our line producer to see if we could get them. Somehow, we almost always did.

Sometimes it'd just be 3-4 shots: an insert of a document or a photograph or a detail. But in a few episodes, entire scenes would need to be filmed again. Or I'd realize that I'd written a scene wrong or needed an additional moment or two that wasn't in the script.

I won't say on what show or episode, but one time I realized in post that the director hadn't filmed reactions of the women in the show. Only the dudes had that coverage. The end result being, the viewer lost connection to the inner lives of our women for the episode.

So, I had to request a series of reaction shots for a half dozen scenes, which hugely improved the episode and the storytelling because it wasn't just the guys who we were allowed to see closely & connect with.

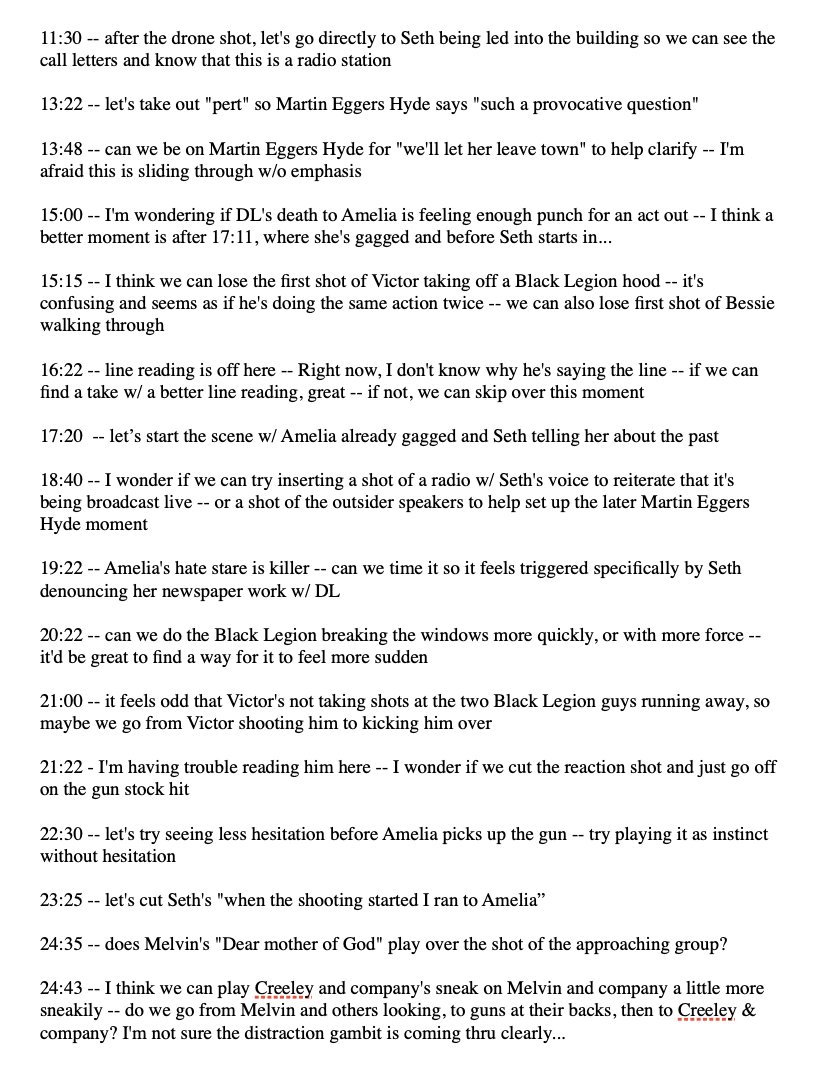

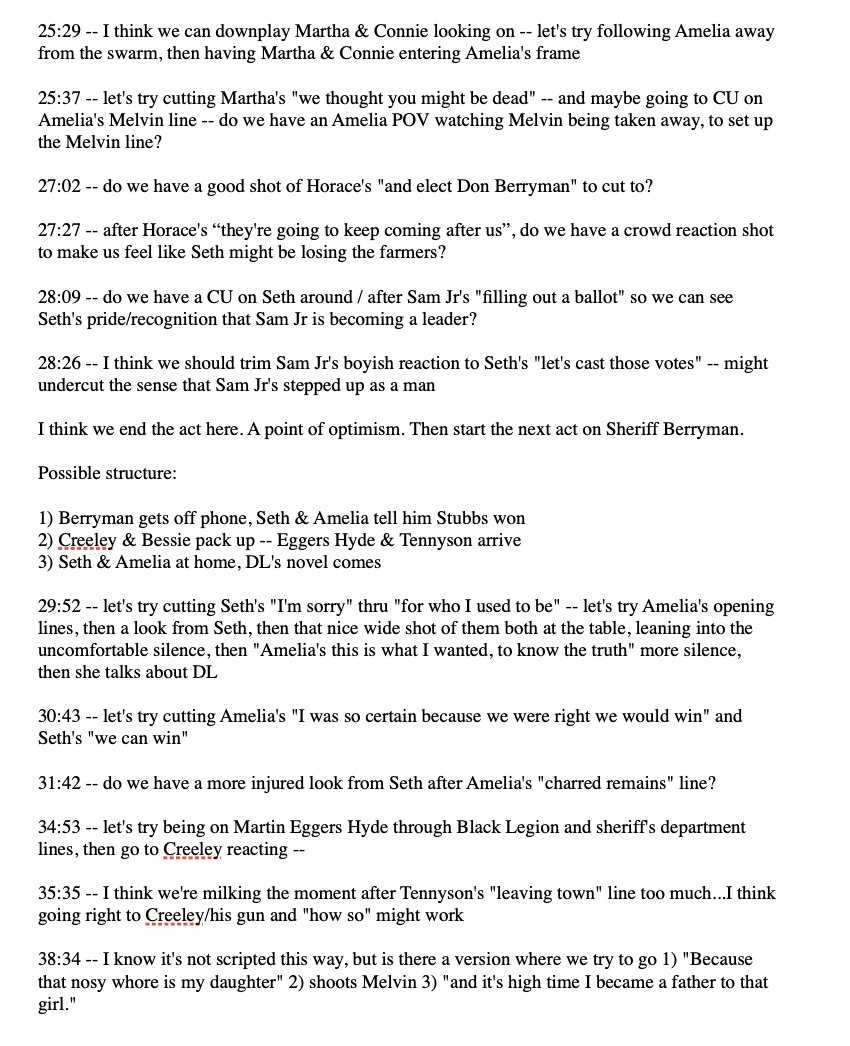

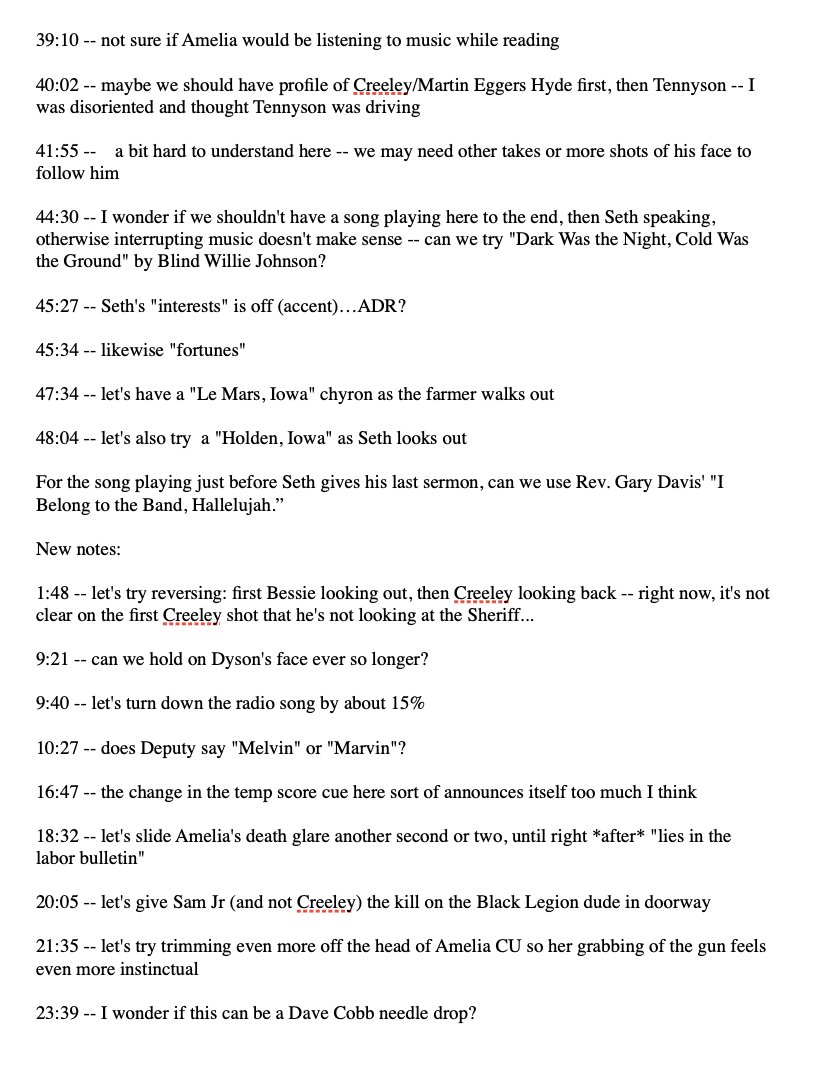

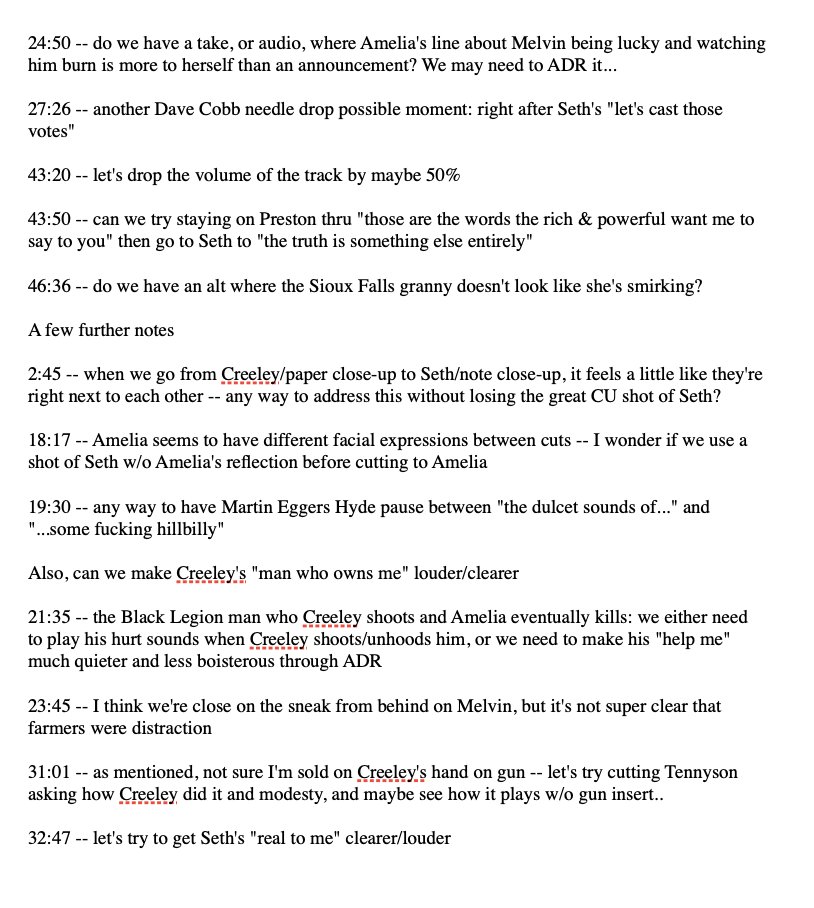

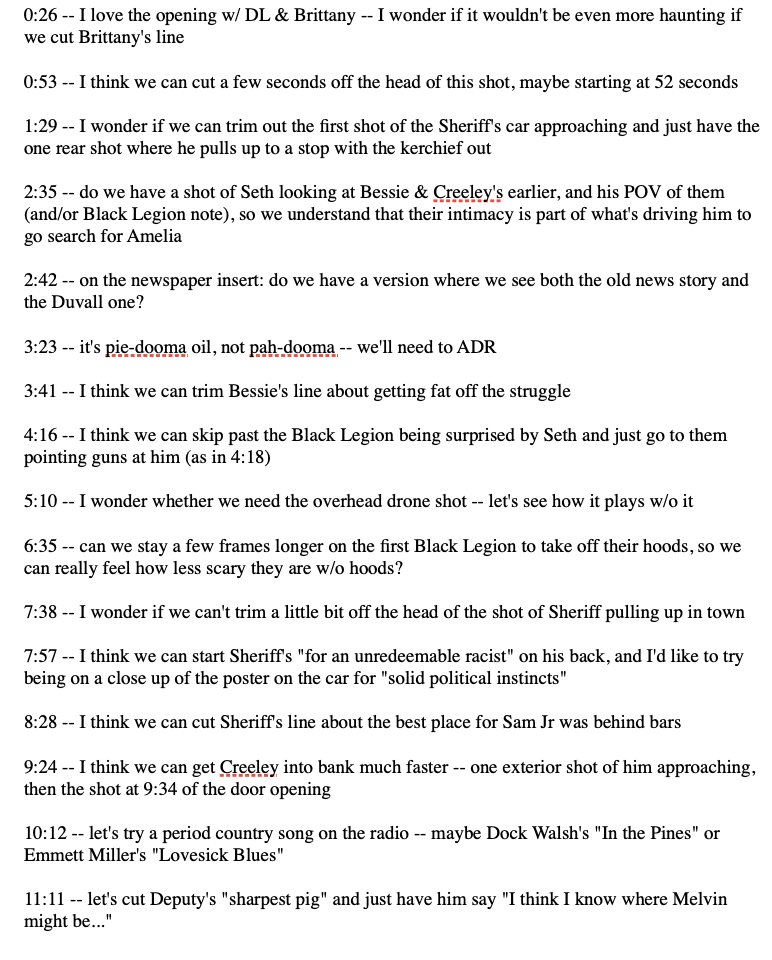

Anyway, after figuring out what (if any) new footage is needed, I then start going through more closely, moment by moment. Here's an excerpt from an email w/ my notes on a DAMNATION episode.

This is from the season (& series😑 ) finale. There are much fewer notes-per-minute here, probably because we were later in the season, & because Adam Kane directed it, & our editor Rachel Goodlett Katz is brilliant. So by the time it got to me, it was just fine-tuning.

Usually, I would email these to Rachel (cc'ing Adam so he could be looped in & interject w/ his opinion) usually late at night after getting the most recent cut. I'd guess it'd take most editors 2-3 days to work through the notes excerpted here.

So now between Adam's 2-3 days, & the next 2-3 days, I'd have maybe two more days on my cut. Since there's so much already going on, I'd usually wait to get into the cutting room for these last couple days. & this is the most fun stage.

At this point, unless the episode is a disaster or I'm delusional, the episode functionally works. It should be close to time, as well. So now I get to spend a day or two just going through it with the editor.

This basically means sitting in a chair & having the editor push play, & us watching it together until something causes me to want to pause. Does the acting feel forced? Is it the wrong angle? Am I getting bored? Restless? We stop & talk about why I'm suddenly out of the drama.

Sometimes the editor has a previous assembly of the scene that got scrapped in the process. They'll cue it up. Maybe something's there. If it's a performance issue, we'll go through every single take until we find one that better captures the moment.

Sometimes we'll run a beat showing both the A & B camera footage of it in split-screen. Maybe the moment actually wants to be seen from the opposite angle. Or, from a different set-up: maybe it plays better in a wide master than in a close-up.

At this point I usually start peppering the editor w/ questions, basically asking them to educate me on their editorial philosophy & underlying principles. I learn a ton that I can carry forward. We try out a couple of different ways to cut the scene/moment. Then push play again.

Basically we repeat this process as far as we can during the work day. If we don't make it to the end of the episode, we pick up where we left off. Once we make it to the end, we rewatch it again & see if anything makes us pause.

I try to remember to ask the editor if there's anything bugging them about the episode, or spots they'd do differently. Sometimes that finds something.

On THE TERROR: INFAMY, I worked with the same editor (Kye Meechan) on all of my episodes. In order to see the cut w/ new eyes, at the end of the producer's cut period, we'd watch a version of the episode in black and white.

But now the period of bliss is over & it's time to invite everyone else to the party. On DAMNATION, I'd share my producer's cut w/ the non-writing EPs the day before my cut was due. They'd then send in notes overnight if they had any. Usually just a couple. Bless them for that.

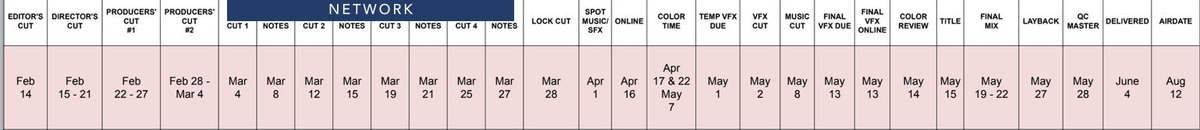

& as this schedule shows, it's then time for the studio/network to give notes. On some shows, that's like two rounds. On others, it can be three or four or more. That means making adjustments, or trying to, or explaining why a particular note won't work. Half art, half diplomacy.

And this is also the point where you really realize whether you're actually making the show that your network & studio thought you were making. Hopefully, the communication has been constant & everyone knows what to expect & you deliver what they think you promised.

Once the cut is locked -- no more changes to the picture itself -- then the more technical phase comes in. You screen the episode with your composer, discussing where you think the score should come in & how it should function.

You screen the episode w/ VFX to talk about what digital effects need to be done: whether it's creating blood spatter, or erasing a modern building from a shot, or smoothing out a frame that has a performance from one take on one half & one from a different take on the other.

On DAMNATION, Tom Yatsko (our DP) & Adam Kane (a former DP) oversaw color timing, but sometimes I'd come to the lab if there was something tricky or if anyone needed another set of eyes.

You'd also screen the episode to spot where you needed loop group (basically, audio-only background) to fill out the audio world, or where you needed to ADR (re-record in a studio) a muffled line, or where you need, say, to add footsteps or the sound of wind for the sound design.

On DAMNATION, I preferred to oversee ADR sessions as much as possible, directing the cast to line readings that fit their lips on the cut but that also got the dialogue over as well as possible. You get some great subtle shit that way.

Finally, once the picture is locked and effects are completed and the sound ingredients are all gathered, it's time for sound mixing. Which is maybe my favorite, favorite stage.

You go to a really really nice theater, where your episode is projected. And you listen as the sound plays on cutting edge speakers. The episode will never look or sound better than this. And your sound team plays the episode, and you write down notes:

let's make the footsteps 10% louder, turn down the music cue slightly, and let's hear more of the loop group for this crowd shot, etc. It usually takes a whole day and you watch/listen to your episode a couple more times until it sounds right to your ears.

Anyway, that's a rundown of my post-production experience, if you're curious, or if you're breaking in and wondering what to expect (tho again, it's just my experience -- every show is different).

I love every stage of it, because to me, it's all writing: but instead of mere words on the page, it's writing with images, performances, music, sound, pace.

Probably the best advice I ever got was from James Mangold during the DAMNATION pilot. In essence, he told me the script doesn't exist anymore, & production doesn't exist anymore. All that exists now is the footage. So find the best story possible lurking in that material.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh