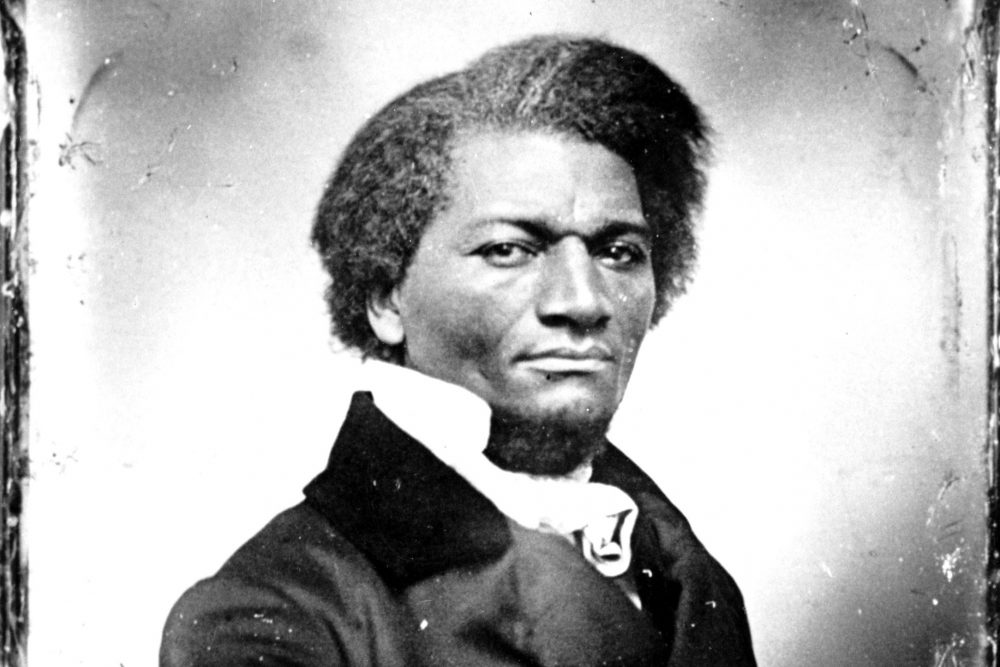

While Frederick Douglass is being recognized more and more nowadays, and his powerful anti-racist arguments are increasingly popular, I think there's another part of his legacy that is overlooked.

This is random, but here's a short thread on Douglass and religious liberty. /1

This is random, but here's a short thread on Douglass and religious liberty. /1

It's sometimes overlooked that Douglass's first job, after escaping slavery, was as a preacher, and many of his literacy lessons came from reading the bible. This, of course, makes sense given his frequent biblical allusions, the number of which always astound my students. /2

Yet a trenchant theme found throughout his abolitionist career was his critique of present religious institutions that supported slavery and, simultaneously, his firm belief in religiosity's importance within the nation. /3

On my most recent reading through his orations & essays, I've been struck by how frequently he brings up the topic of "religious liberty." This is a potent phrase with a long history, of course, but I thought Douglass offered a compelling argument still relevant today. /4

For example, in 1852, he declared that the Fugitive Slave Law, which forced citizens to support the efforts to find and return those who had escaped slavery, was the most flagrant infringement of religious liberty, as it infringed on one's moral compass. /5

“That the Church...does not esteem [it] as a declaration of war against religious liberty, implies [the] Church regards religion simply as a form of worship, an empty ceremony, & not a vital principle, requiring active benevolence, justice, love & good will toward man.” /6

In other words, fraudulent and oppressive federal practices forced infidelity upon all believers residing in the nation, as it made them support policies that betrayed their principles. Douglass claimed the Fugitive Slave Law did more to destroy Christianity than Thomas Paine. /7

This is, I think, a brilliant and needed meditation on what we mean by "religious liberty." Too often, Douglass claims, we equate the phrase with ecclesiastical practices and societal structures that, while important, are actually not the root of religiosity. /8

Instead, we should consider how the oppression of marginalized groups, perpetuated by government/society/communities and validated by complicit/silent churches, is also an indictment of religious convictions, and even a betrayal of our religious liberty to save humanity. /9

This idea hit me especially hard in our present context, where some are decrying health & safety policies designed to save people as attacks on one's freedom to gather & worship. Or, more broadly, claims that protections for privileged classes an erosion of religious liberty. /10

The term "religious liberty" has been colonized by a particular segment of society to defend a partisan collection of ideas. This is the culmination, of course, of the coalition formed between evangelicals and the GOP, as the phrase now reflects conservative priorities. /11

But learning from Douglass, there's power in reclaiming the powerful phrase. Racial oppression, gender discrimination, economic inequality, the literal placement of children in cages--all of these are infringements on religious liberty, our right to create a moral nation. /12

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh