#HistoryKEThread: Is History About To SAP Us Again?

In 1963, after more than a decade’s episode of violent struggle for freedom, Kenya attained her independence.

Then in 1991, roughly 28 years later, Kenya momentarily lost her independence.

Technically, somewhat.

In 1963, after more than a decade’s episode of violent struggle for freedom, Kenya attained her independence.

Then in 1991, roughly 28 years later, Kenya momentarily lost her independence.

Technically, somewhat.

The circumstances in 1991 and those of today were similar. The one thing Kenya didn’t suffer from in the 1990s was the effects of a worldwide pandemic. Otherwise, history is repeating itself.

Interestingly, 2020 is 29 years after 1991. And Kenya, the growing cacophony of “BBI” and “referendum” notwithstanding, is again about to lose her independence.

Technically, somewhat.

Technically, somewhat.

As is the case today, back then corruption and governance issues reigned, the government had borrowed heavily, and struggled to meet external debt obligations owing to an unfavorable balance of payments situation.

Economists tell us that the balance of international payments is the difference between the amount of money flowing into a country within a particular period of time, and the outflow of money to the rest of the world at that time.

When the amount of money flowing out is more than that flowing in, then a country has unfavorable balance of payments.

Nations would rather that inflows are more than its outflows.

Nations would rather that inflows are more than its outflows.

The opposite scenario means that their economies will struggle to meet payment obligations towards other countries.

Such as in servicing debt.

Such as in servicing debt.

In order to wriggle itself out of a tough situation, the cash-strapped administration of President Moi turned to the Bretton Woods Institutions - the World Bank and IMF - for assistance. Engagements begun in the early 1980s.

But nearer 1991, Bretton Woods institutions imposed a raft of tough fiscal and expenditure conditions.

The institutions became President Moi’s pet punching bags. In political rallies across the country, President Moi barely fell short of telling Kenyans that they were under the tough conditions of a new crop of “wabeberu”.

Behind closed doors, IMF/World Bank officials and government of Kenya technocrats engaged in spats, disagreeing on the nature of implementation of economic conditions and the consequences.

That was before the so-called “development partners” arm-twisted Moi to appoint a “Dream Team” made up of eminent technocrats to serve as Permanent Secretaries in crucial ministries.

Led by Palaentologist and Head of Civil Service Dr. Richard Leakey, the Dream Team comprised of Martin Oduor-Otieno, who was plucked from his role as Director of Finance and Planning at Barclays Bank to be PS in Treasury, Magadi Soda Managing Director Titus Naikuni as PS....

.... in the Transport and Communications Ministry Dr. Shem Migot Adholla of the World Bank as PS in the Agriculture Ministry, among others.

According to the Daily Nation, appointment of the Dream Team Permanent Secretaries caught some cabinet ministers off guard. When Martin Oduor-Otieno introduced himself to officers at the Treasury, the Minister at the time, Francis Masakhalia was surprised by the appointment.

“I have been around for a long time”, the Nation quotes the bewildered Minister as telling Mr. Oduor-Otieno (pictured). “One thing I can tell you is that you should take it easy here.”

And just how bad were things then to warrant the appointment of a Dream Team?

In 1993, Kenya’s shilling was devalued by 81%, resulting in the country’s external debt ballooning to 143% of the GDP. In a matter of weeks that year, commodity prices soared, some by up to 3 times.

In 1993, Kenya’s shilling was devalued by 81%, resulting in the country’s external debt ballooning to 143% of the GDP. In a matter of weeks that year, commodity prices soared, some by up to 3 times.

Even the price of table salt, which had not changed much for decades, increased considerably that year.

To ensure that Kenya met her debt repayment obligations, the IMF/World Bank tightened its Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs) on Kenya.

To ensure that Kenya met her debt repayment obligations, the IMF/World Bank tightened its Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs) on Kenya.

According to economist Stanley Fischer, there are two types of SAPs: Short-term microeconomic adjustments, which refer to initiatives geared towards living within your means; and structural adjustment, which means changing the structure of an economy to enable it to grow rapidly.

But SAPs have been criticized by some for being instruments of neo-colonialism for the IMF/World Bank. Anti-globalization activists argue that in many cases, (mostly Western) political conditions are imposed on nations in exchange of economic bail-outs.

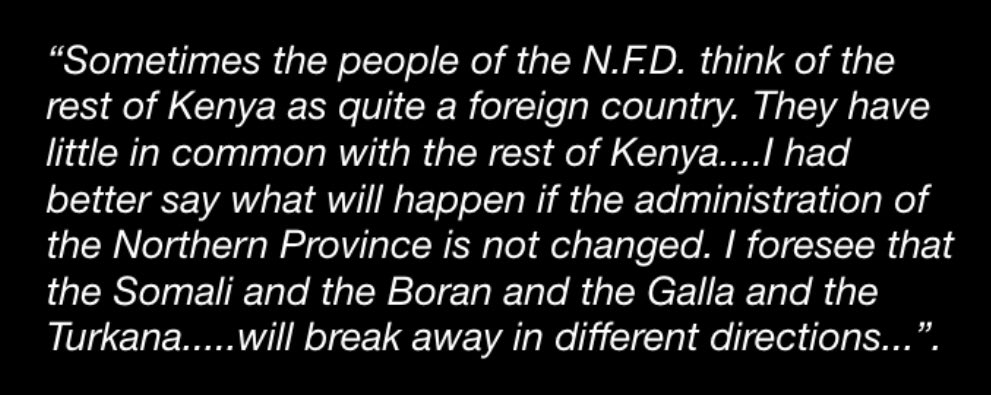

In the case of Kenya, observers pointed out that the donor community, IMF and World Bank went beyond their intended focus on the economy and conditioned aid on introduction of multi-party democracy.

Moreover, critics argue that enforcement of SAPs invariably hits developing nations hard, especially on social aspects of human development, viz. lower per capita income, unemployment, etc.

Kenya, again, was no exception.

Kenya, again, was no exception.

Kenya’s SAPs in the 1990s saw the introduction of cost-sharing in the education sector.

This policy led to low enrolment rates at all levels of education, inability by government to provide sufficient learning resources and, overall, deterioration in the quality of education in the country.

Suddenly, university students found they no longer had access to “boom” (allowances paid to university students for their upkeep). University and secondary school tuition fees were no longer subsidized. Students paid for university tuition, meals, books and even accommodation.

Unable to afford fees, students, particularly from poor communities, dropped out of school.

SAPs also had an adverse effect on real per capita income growth, caused by increased unemployment and poverty levels in the country. The economic chasm between the rich and the poor widened.

In the 1st decade after uhuru in 1963, for instance, salaried employment grew by an average of about 3.5% per year, according to Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. The rate of growth was 4.2% between 1974 and 1979, 3.5% in the 80s and a measly 1.9% at the onset of the 1990s.

KNBS also reported an upsurge in violent crime.

The number of prisoners in Kenya shot up from 106,000 in 1989 to about 112,000 in 1991, 115,600 in 1992 to 124,949 in 1993, and jumped to 130,173 in 1994, when the economy improved slightly.

The number of prisoners in Kenya shot up from 106,000 in 1989 to about 112,000 in 1991, 115,600 in 1992 to 124,949 in 1993, and jumped to 130,173 in 1994, when the economy improved slightly.

Check out the rates of violent crime in Nairobi and how they were inversely proportional to economic performance.

Recently, a section of the media reported that Treasury was in talks with the IMF for budgetary support. The Business Daily put it more bluntly in their headline: “World Bank, IMF FORCE Kenya to seek Sh. 75B debt relief”.

From the look of things, the 90s, and more taxes, are back with us. Minus new jack swing 😔.

The runaway graft, wastage of resources and threats by Treasury to increase taxes all remind me of something that a wise man once told me about history: That the greatest lesson from history is that human beings don’t learn from history.

What truth.

What truth.

The World Bank was founded to “provide financial assistance for the reconstruction of war-ravaged nations and the economic development of less developed countries....”

What irony.

What irony.

We wait and see how the current government should in Kenya will be judged by history

For relevant reading: africanexponent.com/post/7580-how-…

Photo Credits: The Standard, AP, Daily Nation.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh