Yi-hung Liu has a paper—"The World Comes to Iowa in the Cold War: International Writing Program and the Translation of Mao Zedong"—on another part of the American project of shaping Chinese literature. The International Writing Program was started by Paul Engle and his wife...

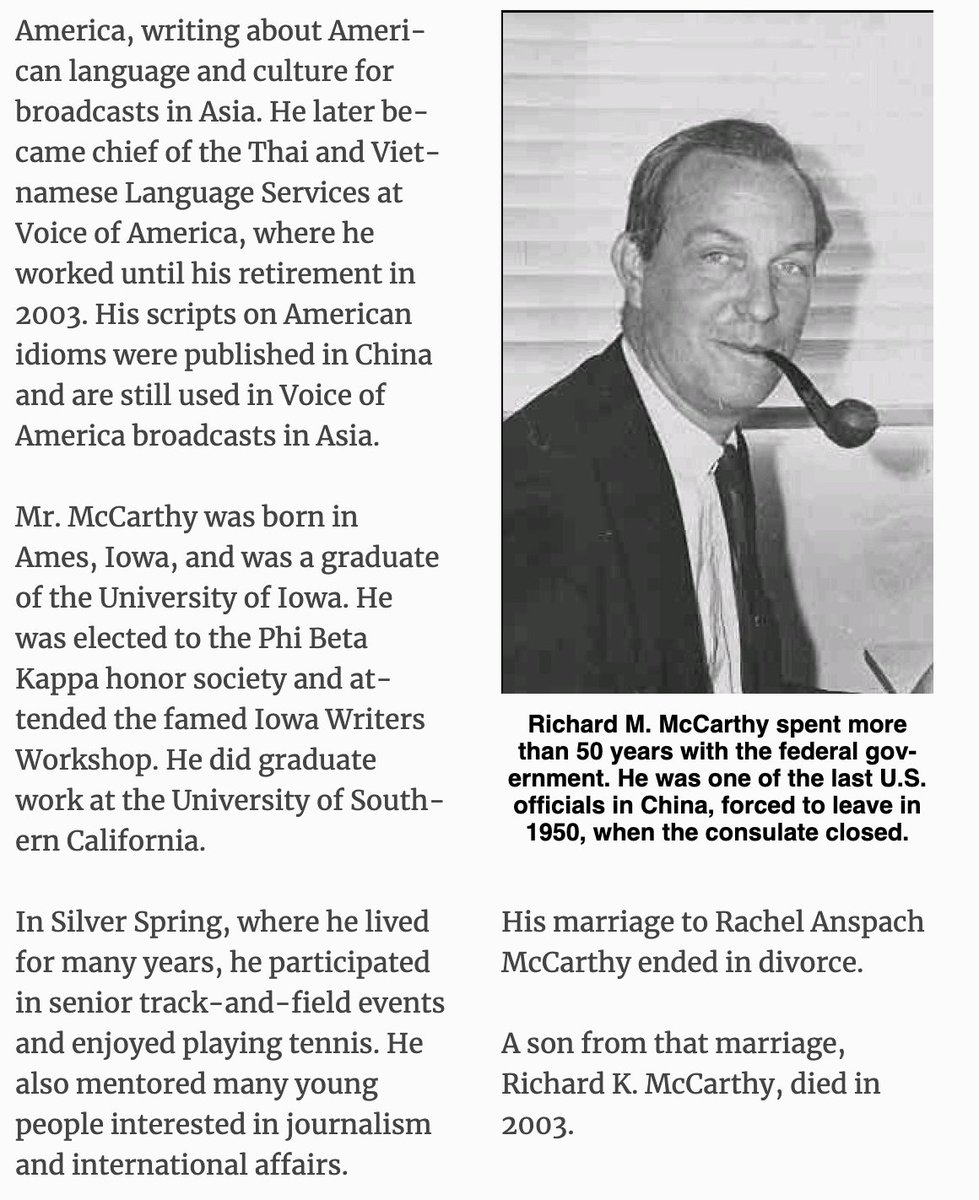

...Hualing Nieh Engle 聂华苓, two members of the Iowa crew that included Richard M. McCarthy, HK USIS head. The CIA had funded Engle's Writers' Workshop, and the IWP was a scheme to bring in writers from outside the free world to hear the gospel of American freedom.

Writers from unfree states were granted a chance at liberation—a "left-liberal ideal of international integration." Like in HK and TW, the emphasis was not on anticommunism, but on individualism, becoming a global citizen (in a world governed by the United States).

"The Chinese from Taiwan and from mainland China ... were sad when they left, knowing they could never meet again. Where else in the world could they live in the same building save in Iowa City?" That list of Chinese writers has some interesting names on it...

The first was Xiao Qian 萧乾, or Ruoping 若萍, in 1979, then Bi Shuowang 毕朔望, and some interesting names after them: Wang Meng, who would go on to serve as Minister of Culture, Ai Qing 艾青, poet and father of Ai Weiwei, Ding Ling 丁玲, already in her late 70s by then...

...Liu Binyan 刘宾雁, Ru Zhijuan 茹志鹃, and her daughter, Wang Anyi 王安忆, Shen Rong 谌容, Ah Cheng 阿城, Bei Dao 北岛, Can Xue 残雪, Liu Sola 刘索拉... Among the younger writers invited in the '80s, it seems clear they were selecting for a certain type, open to the message.

These writers are seen as having held out against communist philosophy. Sussing out which "individual Chinese writers during the Cold War era gave in to or resisted ideological brainwashing has become a critical locus of contestation," as Po-hsi Chen says.

In "Wang Anyi, Taiwan, and the World: The 1983 International Writing Program and Biblical Allusions in Utopian Verses," Chen tells the story of Wang meeting the Taiwanese leftist writer Chen Yingzhen 陈映真, a Marxist rabble-rouser, locked up for stretches by the KMT.

Chen was perhaps appealing to Americans for his dissident status, but his concern for the Third World and the poor, and his "in-depth critique of the capitalist system and of its social ills set him, ironically, into a position opposed to 1980s young mainland Chinese writers."

Writers like Wang Anyi, Ah Cheng, Bei Dao, Can Xue, and Liu Sola signaled the direction that Chinese literature was being rapidly propelled in the 1980s—local over national, individual over group, private over political, esthetic over ideological.

The work at the IWP built on what had been done by folks like McCarthy in HK-TW, funding literary creation in an American mode, translating key Western literary works. There was no need for anticommunism but to push elites in the direction of disengagement with politics.

In the age of depoliticization in the postsocialist PRC, controls on literature slackened. Mainland writers could catch up with their peers in HK-TW, abandoning politics in favor of pure artistic creation.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh