This Day in Labor History: December 1, 1868. A young black former Union soldier named John Henry was among a group of convicts sent from Richmond to West Virginia to blast a railroad tunnel, where he would soon die. Let's talk about the real John Henry, man and myth!

In the aftermath of the Civil War, southern states had no money to hold prisoners. Contracting them all out, or at least the black ones, to coal companies became very common by the late nineteenth century.

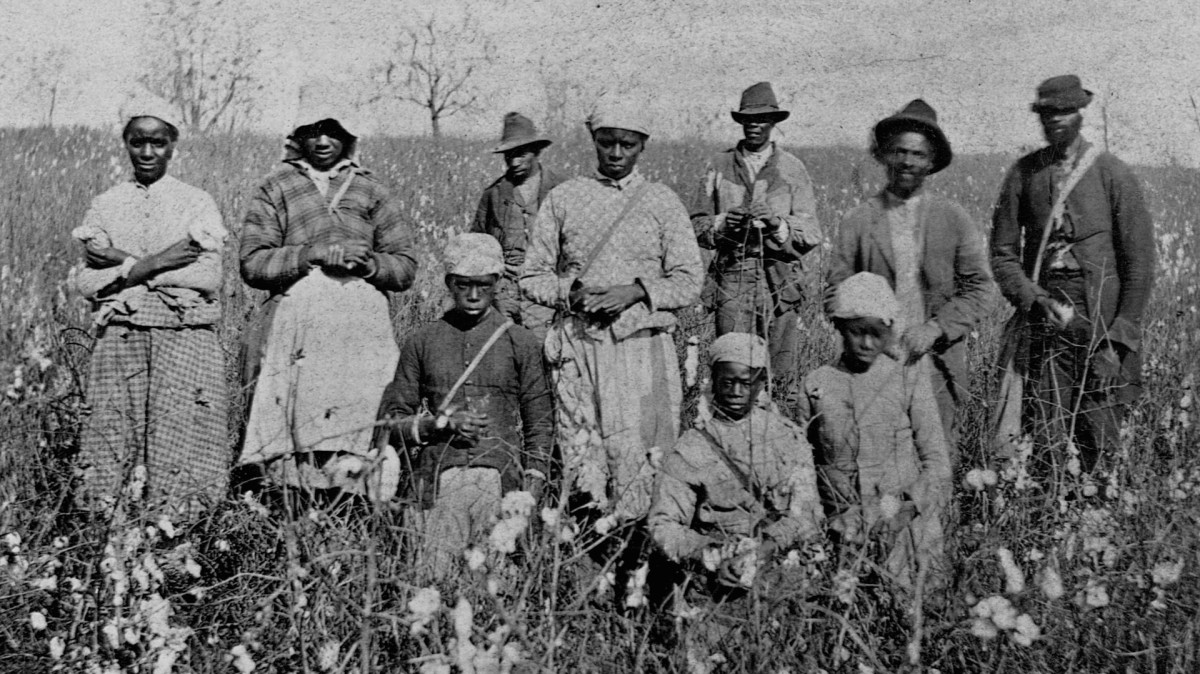

But the first industry to seek free labor from black prisoners was the railroad. Between September 1871 and September 1872, for instance, the Virginia State Penitentiary leased out 380 black prisoners to the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad, of which 48 died on the job.

Among the black men contracted out to the C&O in these years was a very small man named John Henry. He was from Elizabeth City, New Jersey. Only 5 feet, 1 inch tall and born in 1847, he was sentenced to ten years in prison for housebreaking and larceny in November 1866.

Like many northern black men, Henry joined the Army to help other black people fight for freedom. While a few actually fought, mostly they were forced to do the most menial labor, such as gravedigging.

After the Civil War ended, both black soldiers, quickly mustered out of service, and freedmen were gathered to bury the many bodies around Richmond. One was John Henry. He may have done other tasks as well, but we don’t have those records.

The Freedmen’s Bureau was established by 1866 but the quality of the officials running it varied widely. In Prince George County, Virginia, it was headed by a guy named Charles Burd who had been shot in the head at First Manassas and was never the same.

Meanwhile, many black workers were striking by 1866. Like many Freedmen’s Bureau officers, Burd was completely unsympathetic with the freed slaves, identifying with the white South and filled with racism. Burd’s own letters are filled with him complaining about the ex-slaves.

His own successor in the job accused him of being a policeman for hire for employers, calling out his men to put down any kind of organized labor activity by black people. It seems that John Henry was one of the men arrested by these government-employed thugs.

It’s hard to say if he was actually guilty of any crimes, but what we do know is that black men were thrown into prison for anything, especially resisting forced labor.

Burd happily enforced Virginia’s Black Code and Henry was probably caught up in this and thrown into prison. Burd himself was soon fired but this was no help to Henry, sentenced to ten years in the Virginia State Penitentiary, which almost no one could survive.

Henry arrived in the pen on November 16, 1866. If he didn’t already have a scar on him, the guards gave him one to identify him if he fled. The overwhelming majority of prisoners were black, up to 80 percent by early 1867 as Virginia sought to imprison as many as possible.

The prison, now ruled by the military, was shocking. A Radical Republican named Burnham Wardwell was in charge of it and he was horrified at the brutality. But like most Radicals, he strongly believed in the free market.

Seeing life in the prison as a torture chamber, needing to find a way to fund the state, and hoping to find some other option for prisoners, the free market it was. He instituted the convict lease system.

Meanwhile, Collis Huntington, the rapacious railroad capitalist from California, had bought the C&O and he also had introduced the use of nitroglycerin to blast holes through mountains.

Between explosives and new steam drills, Huntington felt he could build a new railroad system in Appalachia if he could get some sweet convicts he could kill without consequence. It was on December 1, 1868 that Henry became one of Huntington’s expendable workers.

The famous “John Henry” songs talk of him competing with a steam drill. Well, Huntington was using those steam drills in 1870 and 1871 while also not using them exclusively.

So a battle between Henry and the steam drill is at least possible and given the centrality of that to the legend, is probably more likely true than not, whatever the result of it.

But we don’t know much. Henry probably died in 1873. His body was shipped back to the state pen in Richmond, where it was dumped in a mass grave that then went undiscovered for well over a century.

Given that about 10 percent of the workers died every year in these convict camps, he was far from alone. Over 100 convicts alone died building the Lewis Tunnel, including Henry. Maybe it was silicosis, maybe an accident, maybe murder by the guards.

We can’t really know precisely how the John Henry story became one of the most important ballads in American musical history.

But we do know how these things spread, which basically is that workers created songs, crafted them existing chants or melodies, and then spread them around when they moved to new jobs, which was frequently.

That seems to be the case with the John Henry stories, which makes extra sense since it was a railroad story at a time that this was a growing industry. By the early twentieth century, folk collectors knew of the song and many versions were published.

The truth of the various stories isn’t that relevant and naturally was mixed with other stories, other worker deaths, other melodies.

In any case, this utterly obscure and oppressed black worker became one of the most famous laborers in all of American history and remains so today. One wonders what he would have thought of this if he ever could have known

I borrowed heavily from Scott Nelson’s excellent 2006 book, Steel Drivin’ Man: John Henry, The Untold Story of an American Legend for this thread. Great book, check it out.

Back tomorrow to discuss the Bhopal gas poisoning of 1984, one of the biggest mass murders by American corporate greed in history.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh