Yesterday, I was among the many folks on here tweeting with some distress over the news that U. Colorado is replacing tenured faculty with NTT instructors to deal with budget shortfalls. I actually have a bit of a different take today. I think it could be a positive step. /thread

This @insidehighered article from the dogged @ColleenFlahert1 provided some very important additional context. Faculty are being bought out voluntarily and those positions replaced with instructors who will teach twice as much. insidehighered.com/news/2020/12/0…

I think this comment from one of CU-Boulder's tenured profs is at the crux of the criticism. Such a move is not consistent with what he (and many) perceive as the mission of a research university.

This is a very fair criticism, but I want to add some context around this issue that I think is important and maybe points the way to a more productive discussion of how we make our public institutions sustainable.

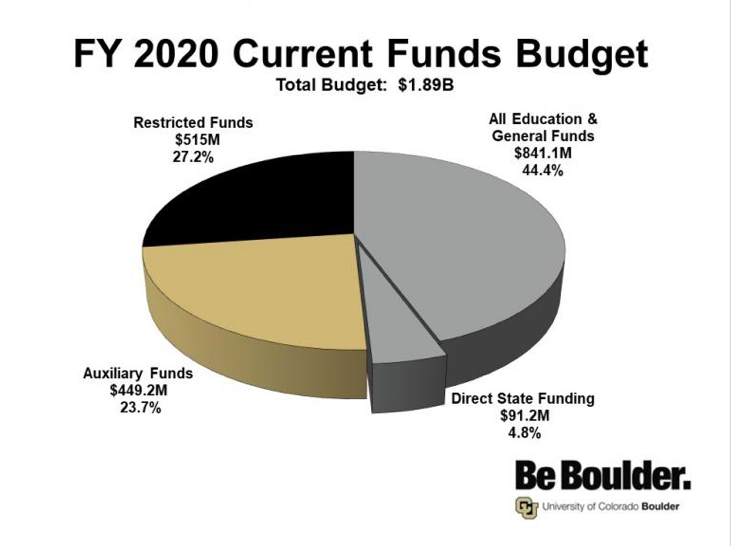

CU has a budget of $1.89B. This is for the whole operation. You can see how that breaks down by category below. Less than 5% of the budget comes from the state. This is not at all unusual.

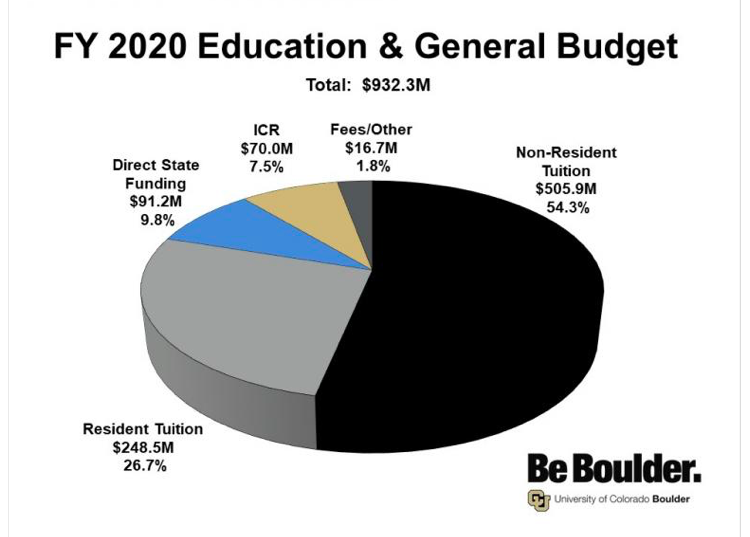

Here is the the breakout of the chunk of the budget that goes directly to education and instruction. Just under half of the total budget. $750M comes direct from student tuition. Note how important out-of-state tuition is.

This means about 40% of the total CU budget is funded by student tuition. But there's one more category of funding that is tied directly to students, Federal Grants. Those are part of restricted funds which totals over $500M.

I could track down how much of the restricted funds is Pell Grant money, but in the interests of time, I can say with high confidence that at least 50% of the entire CU budget (research and all) comes from tuition or grants that are tied to students.

Currently, at Boulder, and other U's like it, student funds (tuition and grants) are going to support the research mission. How much is complicated debatable, but a Berkeley prof calculated that 40% of undergraduate tuition subsidizes faculty research. ocf.berkeley.edu/~schwrtz/DCAM1…

Students at research universities are literally paying tenured faculty to not teach. Holes are then filled by poorly paid, precariously employed adjuncts. This is both an unjust, and as we've seen, unsustainable system. It's the status quo.

In this context, Boulder's move is sensible. They are looking at the source of their revenue, the mission they are seeking to fulfill and putting the revenue toward that mission, instruction. Does it have negative consequences on other parts of the mission? You bet.

What we're seeing, IMO, is the end of this generation of the research university. When that mission was supported by public money, dedicating those funds to supporting research made sense. But students are now funding the university.

Students are not only funding the university, but they're graduating with increasing levels of debt which is causing all kinds of additional societal problems. Again...unsustainable. Cancelling existing debt is necessary, but so is a way forward.

My proposal is to make public colleges and universities tuition-free through a combination of increased federal and state subsidy, with state subsidies required to meet a threshold to qualify for the federal money.

But if this money from public sources is purposed towards making tuition free, we cannot and should not use that to pay faculty to not teach by supporting "departmental research." That money is to support instruction.

I have no wish to kill research. I'm a believer in it, a practicer of it. I've got the CV of a tenured full prof despite a career as a contingent instructor never teaching fewer than 4 courses a semester when I was full-time.

I say this to point out that research is possible when teaching more, though in the end, I am strongly against heaping more requirements on faculty because that too isn't sustainable.

Institutions need to fundamentally rethink their missions and how they will fulfill them. My book puts teaching and learning at the center of the equation. Research happens where there is time, space, and resources. beltpublishing.com/collections/pr…

I am much more focused on non-R1 public higher ed, which would receive a significant boost in funding through something like what I propose, but even R1's must rethink their orientation. We cannot have student tuition prop up work that isn't for students. We just can't.

This will likely mean fewer "research" (tenured) faculty, which means we also have to figure out what a decent, sustainable, secure faculty job looks like in the absence of tenure predicated on research productivity. This is a big hurdle.

I talk about some of the requirements of those kinds of positions in Sustainable. Resilient. Free. by doing a thought exercise around what salaries would like if teaching labor paid an equitable wage across rank. The chapter is an update of this post. insidehighered.com/blogs/just-vis…

If the CU jobs for instructors pay an equitable wage, have some guarantees of academic freedom and job protection, they are a step in the right direction towards sustainability, rather than an harbinger of doom.

This will be a different institution than what we have now, but I can't say it enough, what we have now is not sustainable, so the institutions must evolve. Doing that in a way that's consistent with the mission of education is the key. beltpublishing.com/products/susta…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh