Today's Online Harms consultation response is perhaps the first major UK divergence from a big principle of EU law not tied to Brexit directly: it explicitly proposes a measure ignoring the prohibition on requiring intermediaries like platforms to generally monitor content.

the e-Commerce Directive art 15 prohibits member states from requiring internet intermediaries to actively look for illegal content; this is because the awareness would make them liable.

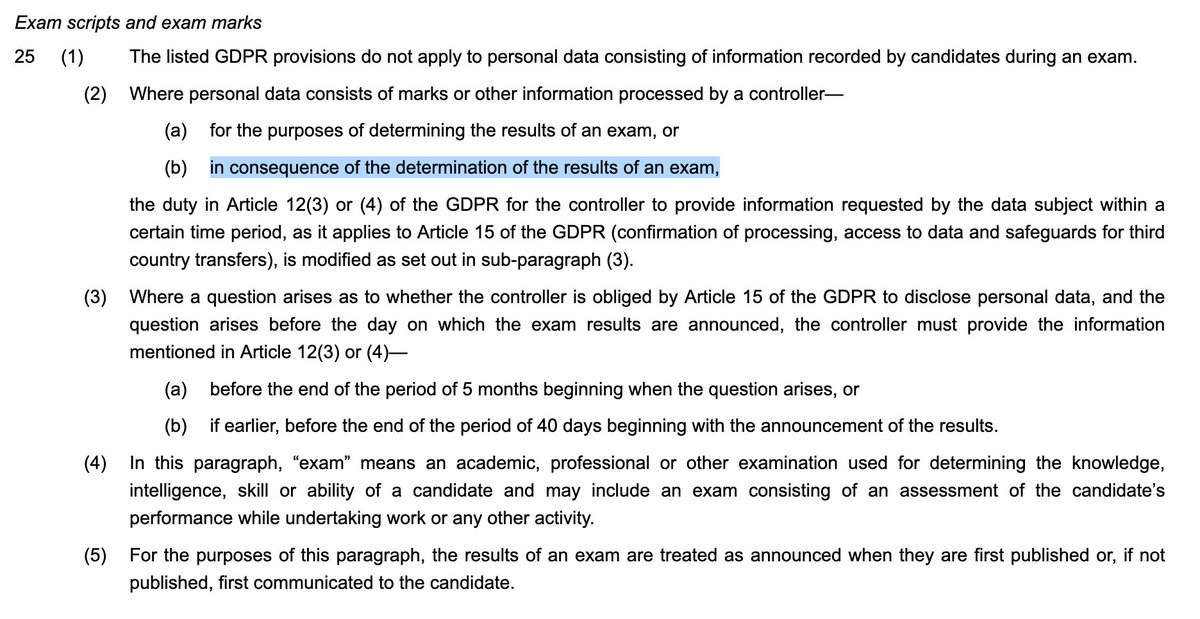

The Online Harms White Paper roughly kept with this, indicating that automatic detection systems were an approach platforms could use, but they would not be required to. Consultation responses (unsurprisingly) agreed.

The consultation response states that in child protection and terrorist content, the regulator will be given a power to require the use of automated detection tools, if it can show necessity, proportionality, accuracy.

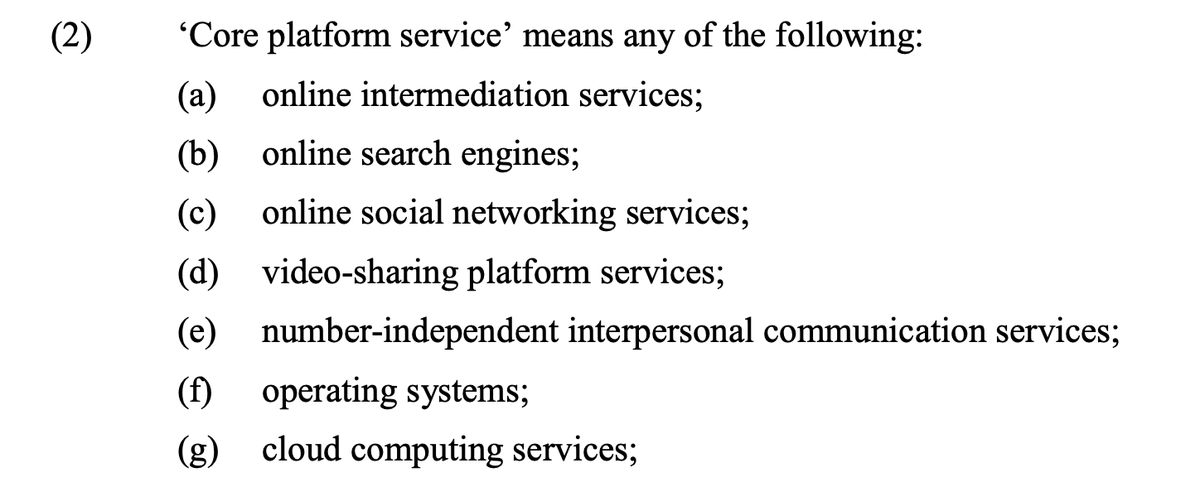

In contrast, the EU's Digital Services Act maintains the general monitoring prohibition (and indeed moves it into a Regulation).

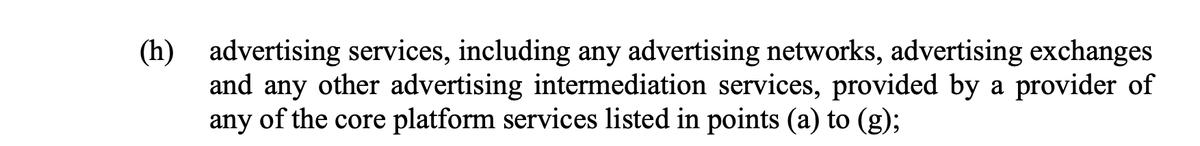

The general monitoring prohibition is a weird beast in retained law — it is in a directive: essentially, MS would be in breach of EU law for introducing an obligation in legislation/court/etc, but never needed to be transposed into UK law directly legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2002/2013….

While UK courts have referred to it in case-law, this puts it in a strange situation — Parliament can always make a law ignoring a prohibition even if it was transposed. Just could not in practice if it was a regulation or Directive.

The prob here is it's magical thinking to think that automated tools can accurately deal with this problem. They can certainly find a subset of already-seen material that is pretty objectively CSAM or terrorist content. They can't deal with the grey areas journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.11…

Anyway, here's the response to the OH consultation. gov.uk/government/con…

Notably missing is any requirement for sharing of these techs. Only largest firms will be able to obtain, maintain, train good automated systems. Huge barrier to entry for new entrants in social media or other communications technologies. OH hasn't thought of competition issues.

If you want some more reading on the state of the general monitoring prohibition, here's some from @AlexandraQu papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf… law.kuleuven.be/citip/blog/to-…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh