It is right to ask *why* industries like fishing have declined. The problem is the blithe assumption that the answer must always be "because of the EU". The problems facing the UK fishing industry long predate EU membership, and will not be magically solved by Brexit. [THREAD]

https://twitter.com/MrHarryCole/status/1339700283396505606

1. Fishing had been declining for much of the twentieth century. The number of UK fishermen more than halved in mid-century: from nearly 48,000 in 1938 to 21,000 in 1970. By 1970 - the year *before* the UK signed the Treaty of Accession - fishing made up less than 0.1% of UK GDP.

2. That decline had many causes. A century of over-fishing had left stocks dangerously depleted. Younger generations were moving out, in search of safer and better-paid work inland. And the "Cod Wars" with Iceland (1958-76) triggered the collapse of the Atlantic trawler fleet.

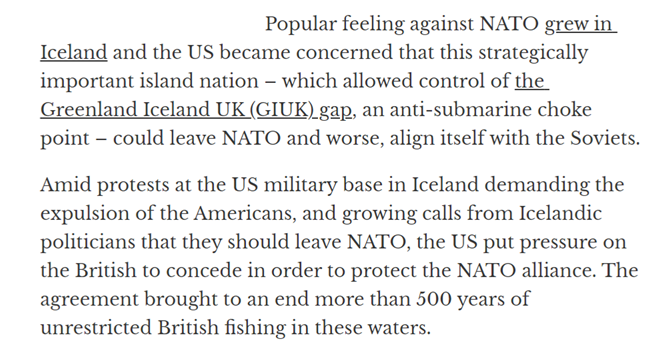

3. The "Cod Wars", in which Iceland expelled GB trawlers from its waters, were a grim reminder (a) that other states have sovereignty too & (b) that power-politics still exist outside the EU. For Cold-War reasons, the US backed Iceland. The UK had to fold. theconversation.com/fish-fights-br…

3. The "Cod Wars", in which Iceland expelled GB trawlers from its waters, were a grim reminder (a) that other states have sovereignty too & (b) that power-politics still exist outside the EU. For Cold-War reasons, the US backed Iceland. The UK had to fold. theconversation.com/fish-fights-br…

4. There were other challenges, too. In the early 1970s, Norway & Iceland were dumping large quantities of frozen fish on the British market, driving down prices for domestic suppliers. The fishing fleet badly needed investment for modernisation but was struggling to raise funds.

5. EEC membership did not solve all the problems facing British fishing, but nor did it create them. Before 1970, a sovereign UK government had proven singularly unwilling - perhaps unable - to arrest the collapse of an industry that an official described as "economic peanuts".

6. It was the UK government that made fishing quotas more easily tradeable in the 1990s, accelerating their sale to overseas fleets. The number of UK fishermen declined from 20,000 in 1994 to c.12,000. Landings by the home fleet fell from 726,000 tonnes to 391,000.

7. In fishing, as in much else, blaming the EU became a substitute for serious thought about what kind of fishing industry we want, how much we're willing to pay for it, how we balance it against other interests & how we manage stocks, as oceans warm & great-power rivalry hots up

8. The challenges facing the UK fishing industry did not begin with the EU & will not be solved magically by leaving. The UK failed to address those problems before 1970. It will fail again, unless it stops blaming the EU bogeyman for much longer & deeper problems of policy. ENDS

PS: If you're interested in the history of the "Cod Wars" - and who isn't? - the President of Iceland, Guðni Thorlacius Jóhannesson, wrote a PhD on the subject at @QMHistory. The full text is available here: qmro.qmul.ac.uk/xmlui/handle/1…

4. There were other challenges, too. In the early 1970s, Norway & Iceland were dumping large quantities of frozen fish on the British market, driving down prices for domestic suppliers. The fishing fleet badly needed investment for modernisation but was struggling to raise funds.

5. EEC membership did not solve all the problems facing British fishing, but nor did it create them. Before 1970, a sovereign UK government had proven singularly unwilling - perhaps unable - to arrest the collapse of an industry that an official described as "economic peanuts".

6. It was the UK government that made fishing quotas more easily tradeable in the 1990s, accelerating their sale to overseas fleets. The number of UK fishermen declined from 20,000 in 1994 to c.12,000. Landings by the home fleet fell from 726,000 tonnes to 391,000.

7. In fishing, as in much else, blaming the EU became a substitute for serious thought about what kind of fishing industry we want, how much we're willing to pay for it, how we balance it against other interests & how we manage stocks, as oceans warm & great-power rivalry hots up

8. The challenges facing the UK fishing industry did not begin with the EU & will not be solved magically by leaving. The UK failed to address those problems before 1970. It will fail again, unless it stops blaming the EU bogeyman for much longer & deeper problems of policy. ENDS

PS: If you're interested in the history of the "Cod Wars" - and who isn't? - the President of Iceland, Guðni Thorlacius Jóhannesson, wrote a PhD on the subject at @QMHistory. The full text is available here: qmro.qmul.ac.uk/xmlui/handle/1…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh