Fact 23: Not all "cuneiform writing" actually meant something. Sometimes just imitating the general appearance of cuneiform-like signs could be enough — why bother to learn the whole complex writing system if others can't read it anyway?

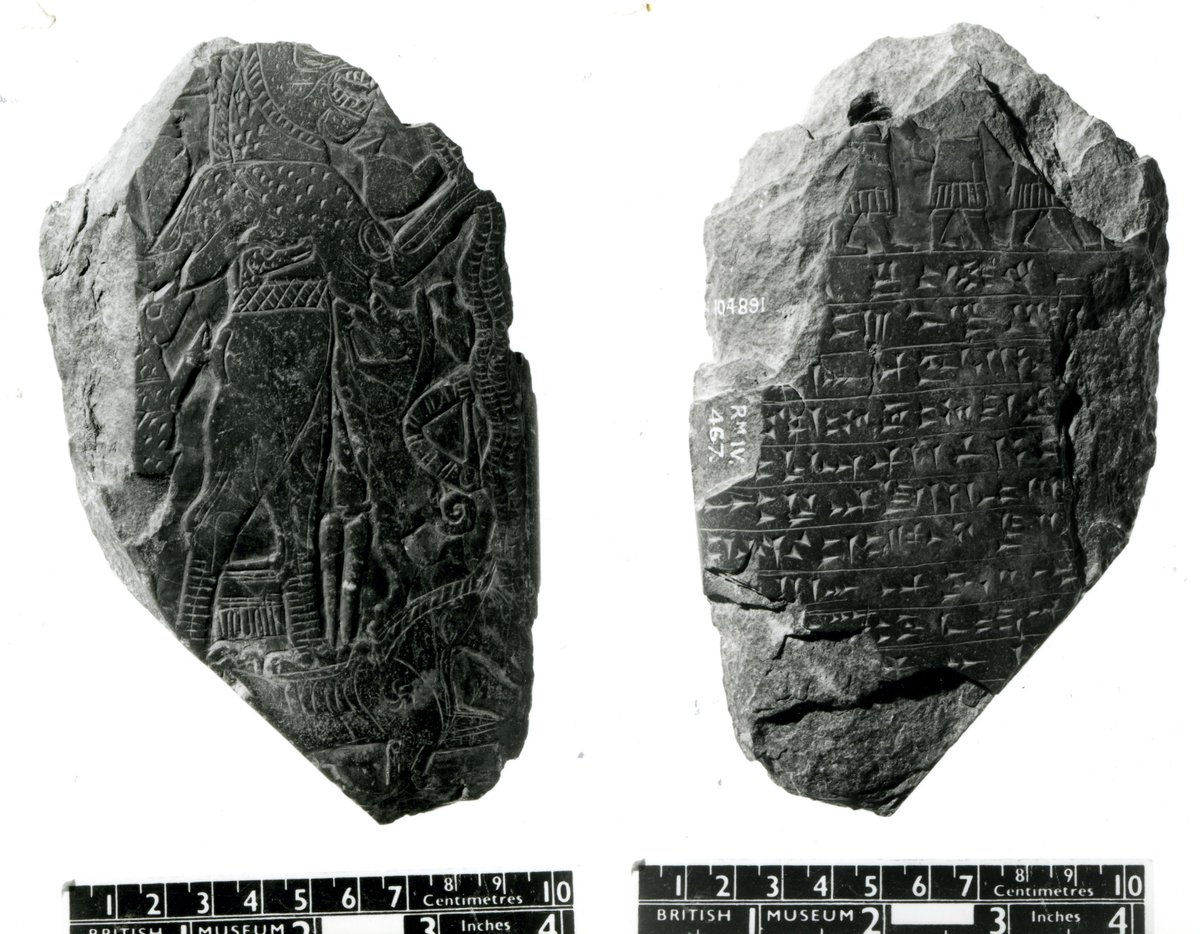

Such “pseudo-cuneiform” text is known from some seals and charms, like these Lamaštu amulets (britishmuseum.org/collection/obj… & britishmuseum.org/collection/obj…). Presumably the intended viewers couldn't read cuneiform, so it didn't matter if the signs were nonsense. They still looked impressive!

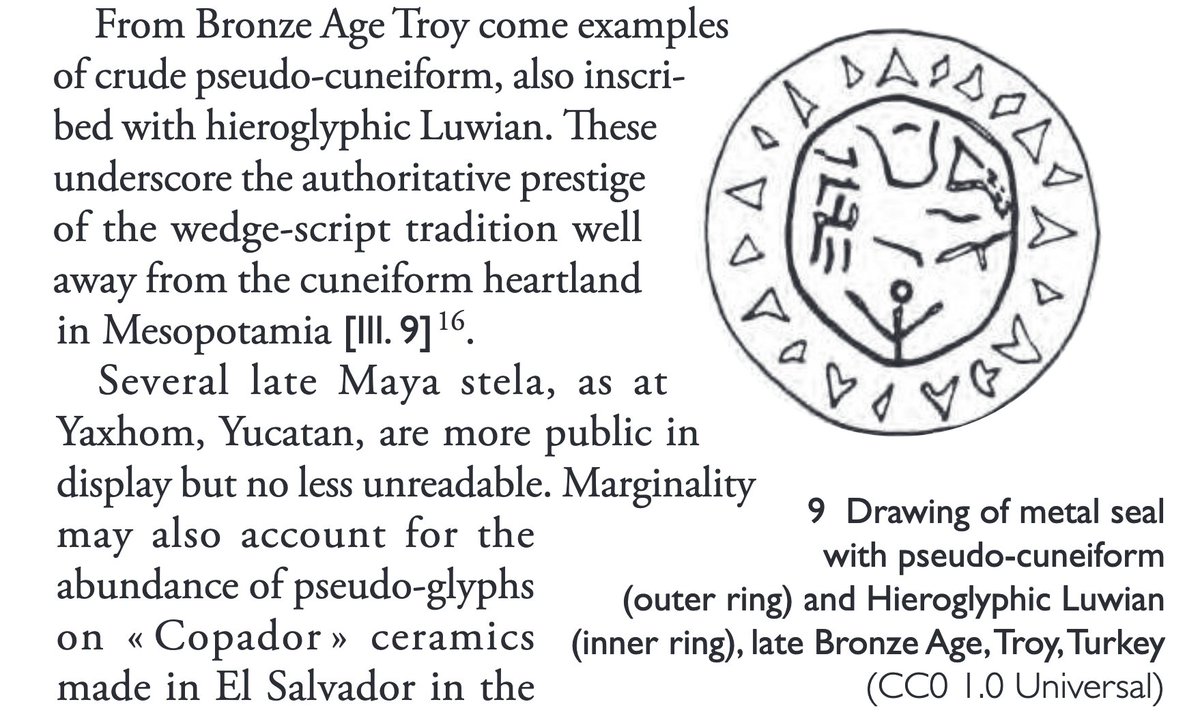

Of course, such “pseudo-writing” is not restricted to cuneiform, but is found all over the world and for all writing systems. For a nice overview, see e.g. Houston 2018, “Writing that Isn’t: Pseudo-Scripts in Comparative View”, cairn.info/revue-l-homme-…

In fact, some authors have suggested that “pseudo-texts are relatively rare in cuneiform” (Veldhuis, via Houston 2018) — of course excluding modern fake antiquities, which we already mentioned in a previous thread a few days ago:

https://twitter.com/cooleiform/status/1340568431574327296

Certainly they seem to be a lot harder to find than I expected! The few images above are pretty much all we found while researching (a.k.a. googling) material for this thread. I'm sure more are known in the literature, but my usually decent web search skills are failing me here.

So instead of sticking to my original topic, let me digress a bit. Because what I did find instead was sort of interesting too, if not quite what I was planning to make this thread about. 😃

At first I tried just searching for “pseudocuneiform” on Google, but the first result I got (after Wikipedia) was this patent for a “pseudo-cuneiform tactile display” for blind readers: patents.google.com/patent/US20060… 😮 And the rest of the results weren’t much more relevant, either.

Another curious search result I got was this medal from 1987, featuring Nebuchadnezzar II and Saddam Hussein(!) and described by the @britishmuseum as having “pseudocuneiform inscriptions” on both sides: britishmuseum.org/collection/obj… I think they're wrong, though!

The inscription on the reverse seems to be actual Old Babylonian cuneiform, with the Sumerian name of the city of Babylon, KA.DINGIR.RA{ki}, clearly readable on the right. Alas, the rest of the inscription (except for the sign AN on the lower left) is worn out and hard to read.

Luckily myvimu.com/exhibit/546399… shows the top three signs to be ki-šár-ra, meaning "of the whole world" in Sumerian. What I'm unsure of is the sign before them that looks like U+AB. I'm 90% sure it's a real sign, since the rest of the text makes sense, but I don't recognize it.

In context, I'd rather like to read it as ezen = "festival", but it doesn't quite match any variant of that sign listed in Labat. Maybe it's a (modern) scribal error?

Also, can anyone here read the non-English text on the obverse? I think it might be stylized Arabic, but since none of us can actually read even normal Arabic… (I know, being able to read Akkadian but not Arabic seems kind of backwards. What can I say? It’s on my to do list.🙄)

Anyway, sorry for the random digression. Unless of course you find trying to decipher a modern cuneiform inscription from the 1980s as interesting as I do, in which case I'm not sorry at all. 😁 And if you know any good references for ancient pseudo-cuneiform text, let me know!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh