Christmas Trinity: Only the Son is incarnate, but the incarnation is the work of the whole Trinity. You can see why a distinction is helpful here: to recognize the undivided work of God toward us, but to specify the Son's incarnation exclusively.

Luther loved to use a homey image for this (one which he attributed to Bonaventure). The incarnation is like three girls putting a garment onto one of them: all three put it on, but only one has it put onto her.

Is it possible to be more precise? Well, although the work is undivided, the distinct persons are evident in the incarnation in a way that corresponds to their order of existence within the eternal relations: the Father unbegotten, the Son begotten, the Spirit proceeding.

Let's take the Father first: Just as he is the eternal origin of the Son, he is source of the Son's sending. The Father's sending of the Son is an extension of the Son's eternal begetting or generation. A real trinitarian mission makes known the eternal procession behind it.

This is why the Bible declares that the Father sends the Son: because this sending extends, or makes present among us, an eternal relation. Less specifically, we might say the Trinity sends the Son (or even that the Son sends himself!), but that's loose talk.

What I mean by loose, or non-specific, is that to say the Trinity sends the Son would be to treat all divine actions as if they were trinitarian missions. Missions are special (they reveal processions). The Trinity stands behind the incarnation not as sender, but as cause.

Compared to mission, cause is shallow & common. Heck, I'm caused by God, but I'm not sent by God in a way that reveals my eternal procession from him! What stands behind the incarnation in the deeper sense is the Son's sending by the Father.

Second, the Son: He takes the human nature onto himself in the sense of uniting it personally to himself (hypostatic union), so that it is his. So it is the work of the whole Trinity, but it terminates on the Son exclusively.

How the Son's trinitarian order of existence shows up in the incarnation is obvious: eternally begotten of the Father, he is now born of Mary. Some early theologians (esp. Hilary of Poitiers) would speak of the Son's two births: one eternal & divine, one temporal & created.

A little word-play on birth here, from Latin to English: to be born is to be natus, to have a nativity. It is also to have the property of natality (an archaic word, the opposite of mortality). That is, it's to have a nat-ure. Two births means two natures. (Feliz navidad!)

For the eternal Son of God to be hypostatically present as the temporal son of Mary is so right, so fitting, so super-appropriate, that theologians have always been tempted to say it was necessarily the Son who became incarnate. (Best not to use "necessary" that way, though.)

Third, the Spirit: Following Scripture, we appropriate to the Spirit the uniting of the created nature to the person of the Son ("conceived by the Holy Spirit," as the creed summarizes Luke's way of speaking).

To call the Spirit's work here an appropriation is to deny that it's proper in the sense of being exclusive. It's not that we exclude the Father & Son from the work, but that by naming the Spirit in it we acknowledge how his eternal relation to Father & Son illuminates the work.

What happens to humanity in the Son's incarnation is an infusing or in-breathing of divine life into creaturely reality, which is instructively analogous to the breathing of a created life-principle into humanity at creation.

So that's roughly how Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are involved in the incarnation of the Son. We could say more, not so much because we're perplexed & trying to solve a problem, as because we are pondering something fathomlessly deep and inviting.

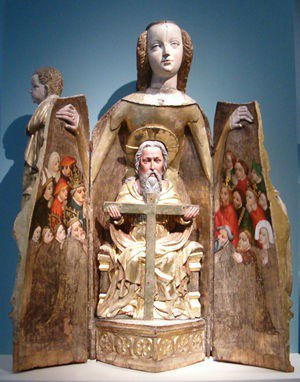

There is a way in which the incarnation opens up to show the work of the entire Trinity, undivided yet corresponding to their eternal order of subsisting. Of course there are also bad ways of approaching that insight: consider the confusing sculptures called "Vierge Ouvrante..."

These are statues of Mary with hinges that swing open to show the Trinity & atonement inside. About 200 are extant from the middle ages, but they were condemned even in their time. The main problem? It just looks like Mary's baby is the triune God. That's not right.

Mary's baby is God the Son, one of the Trinity, bearing the one divine nature in hypostatic union with created human nature, in an undivided work of the Trinity for our salvation, terminating on the incarnation of the Son alone --the Son who was never alone in this work.

Merry trinitarian Christmas! We are celebrating the felicitous nativity of the Lord, in which the three persons of the Trinity put our created nature onto one person of the Trinity, for our salvation.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh