This paper is very cool: behavior oracles in interactive systems that reveal successful decryption can, with a bunch of different AEADs incl. GCM and Chapoly, discern which specific key was used in something resembling log k queries. eprint.iacr.org/2020/1491.pdf

It’s based in part on the idea of “non-committing AEADs”, which are, roughly, AEADs where the specific key used to encrypt isn’t encoded into the output. For something like GCM, this means it’s straightforward to generate K_1, K_2, and C which decrypts under K_1 and K_2.

I found Shay Gueron’s writeup on key committing AEADs to be pretty accessible (I’m just reading casually), with worked examples. eprint.iacr.org/2020/1153.pdf

Anyways, this stuff is problematic for password-based systems; if you’ve got a system that will reveal whether decryption succeeded (super common!) and you can make a C compatible with K_1, K_2, you can for instance guess multiple passwords with each query.

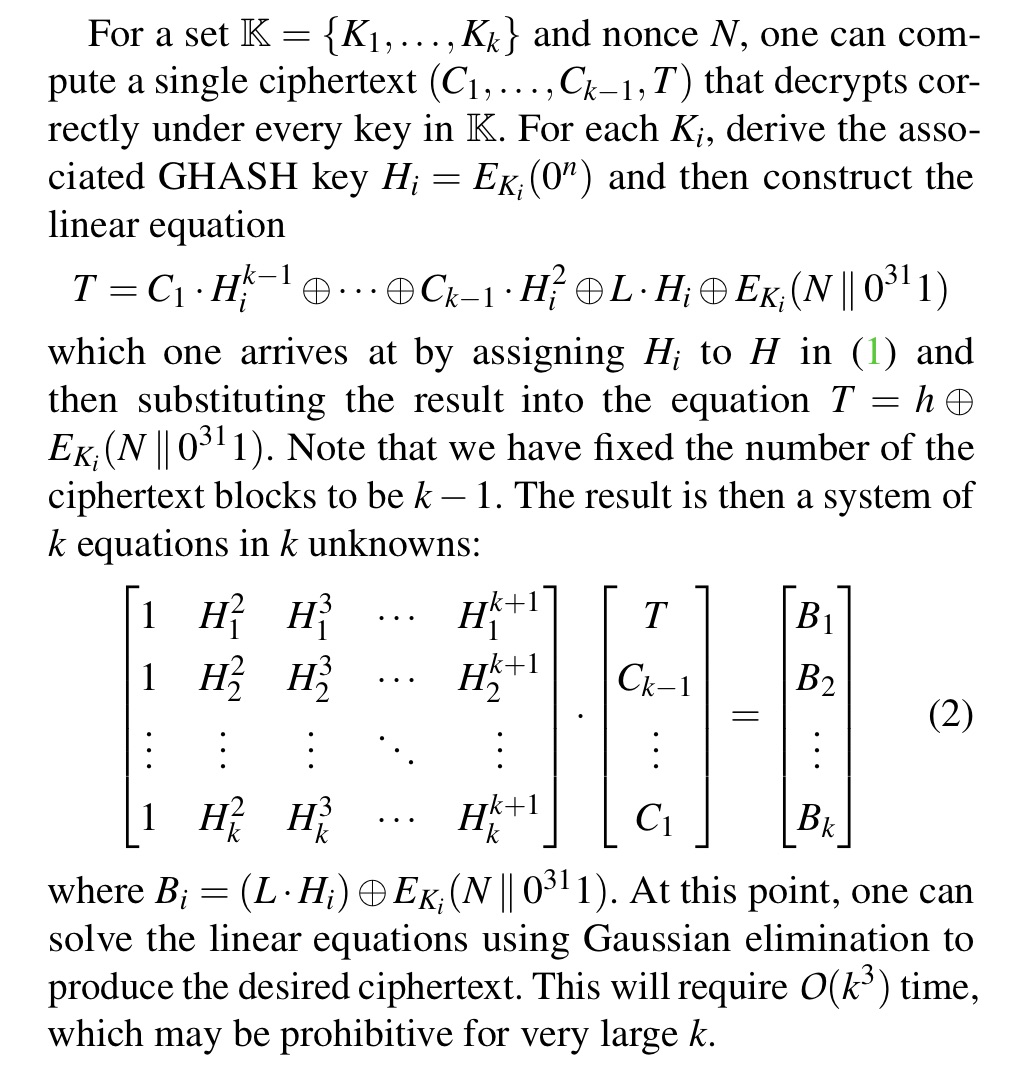

An “oh shit” insight here is multicollisions; generally the idea of, given a K_1 and K_2, we can often easily find K_n. For instance, with GCM, we can do it with Gaussian elimination (albeit clumsily)

(Sean wrote up a simpler, unrelated multicollision attach in Set 7, with MD5/SHA-style hashes; read down to “How?” to see the intuition for it, and maybe just implement it, b/c that exercise is p. great cryptopals.com/sets/7/challen…)

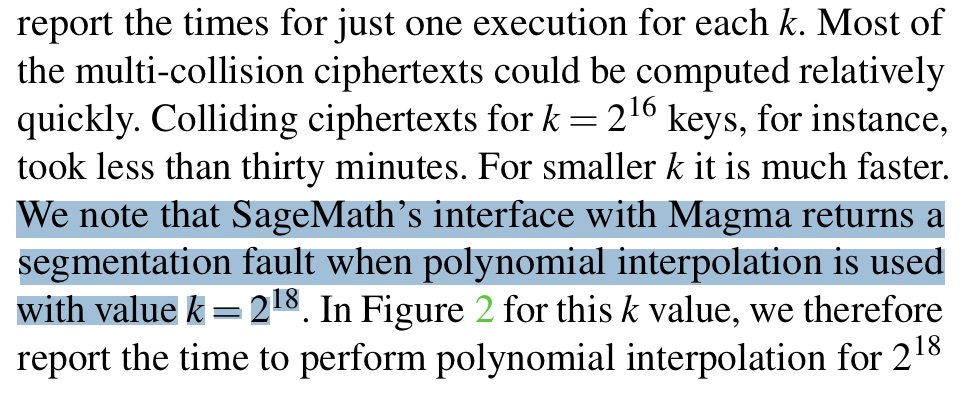

Anyways the GCM key multicollision is more complicated but totally feasible modulo crashing Sage if you try to collide 260k keys into a single ciphertext.

So you have these interactive systems

* whose keys are derived from passwords, so there’s a relatively small universe of possible keys

* that reveal whether decryption succeeded (super common property!)

* built on non-committing AEADs that we can collide lots of keys with

* whose keys are derived from passwords, so there’s a relatively small universe of possible keys

* that reveal whether decryption succeeded (super common property!)

* built on non-committing AEADs that we can collide lots of keys with

So: iterate querying the system for huge batches of passwords at a time (by creating the frankenciphertext that successfully decrypts for, like, 259k different passwords); when you get a hit, refine by querying for subsets of those passwords. Yikes!

(I don’t know how practical any of this is in reality; the 260k-password franken-GCM is like 4 megs long and takes like 5 hours to generate.)

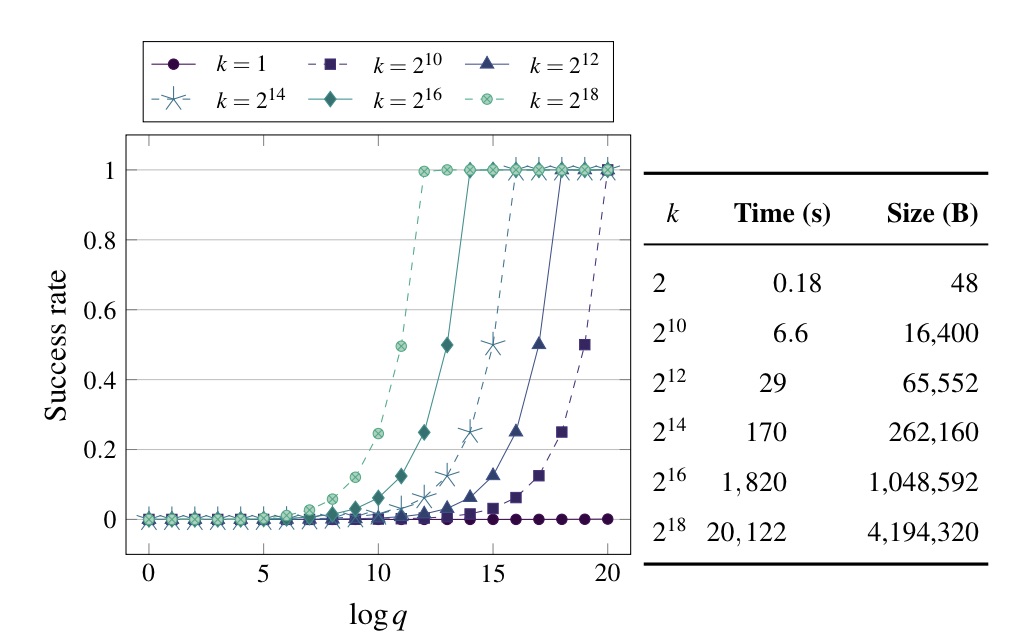

Interestingly: Poly1305 is conceptually vulnerable to the same attack, but its engineering details make the attack much harder to carry out, which is very on-brand.

The authors use this attack to break Shadowsocks, which uses handshake messages encrypted w/ GCM keyed by HKDF(H(pw), salt). On successful decrypt, Shadowsocks opens a listening ephemeral UDP port, which you can just scan for.

If I’m reading this right, Shadowsocks is considerably worse than the sort of generic oracle-vulnerable target; once you get a hit on your initial iterated query, it responds with something you can trial-decrypt offline.

Thanks for @FiloSottile for calling this paper out on his AMA yesterday; it’s one of the neater crypto attacks I’ve read about in the last couple years.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh